NOAA Teacher at Sea

Denise Harrington

Aboard NOAA Ship Oregon II

September 16-30, 2016

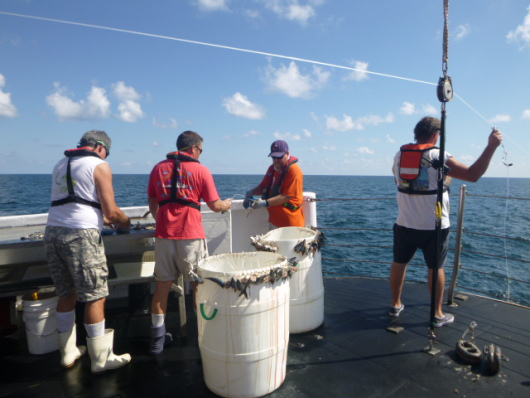

Mission: Longline Survey

Geographic Area: Gulf of Mexico

Date: Tuesday, October 18, 2016

Location: 45o 27’19″ N 123o 50’33″ W, Tillamook, Oregon

Weather: Rainy, windy, cloudy, and cold (nothing like the Gulf of Mexico).

Meet a Scientist: Dr. William “Trey” Driggers

Trey Drigger’s passion for aquatic predators was born in a lake at his grandparents’ house in Florida, while his dad, a jet pilot, was off fighting in the war in Vietnam. When his dad left, Trey’s mom loaded the two boys and two dogs into the car and headed north to her parents’ lakefront home in Florida. Soon thereafter, one of the dogs, used to swimming in safer waters, got eaten by an alligator that lived in the lake. Trey feared the gators but also must have been fascinated by the life and death struggle between two animals.

With thoughts of fighter pilots and alligators, Trey was one of those students teachers might find challenging. He had trouble focusing on the mundane. But through books, he could get a little bit of the thrill he sought.

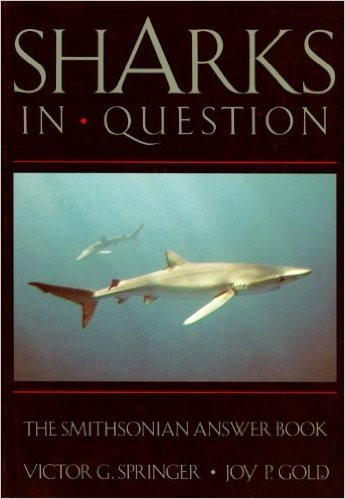

He knew he was destined to do something cool, just like his dad. Yet by the end of college Trey was still unsure of what he wanted to become. One day, he was in the library when the spine of a book caught his eye: Sharks Attack. After reading this book his childhood fascination with aquatic predators was reinvigorated. During a trip to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, Trey purchased a book entitled “Sharks in Question.” The last chapter was about how to become a shark specialist. What, he thought, I can make a living studying sharks?!

Trey quickly finished up his history degree and began two years of science classes he had missed. In Marine Science 101, the professor said “If you are here for sharks, whales, or dolphins, you can leave right now.” Trey took the warning as a challenge, and began his now spectacular career with sharks.

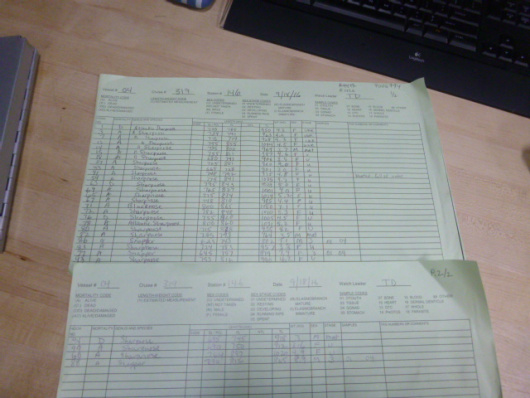

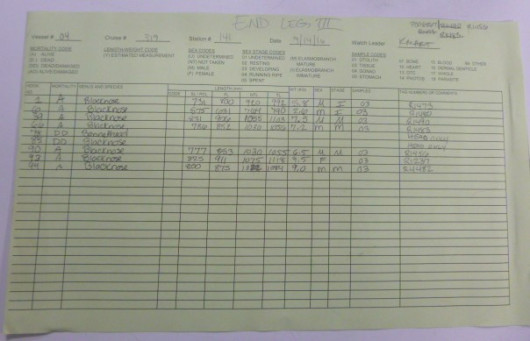

Trey and Chief Boatswain Tim Martin measure a sandbar (Carcharhinus plumbeus) shark while fisheries biologist, Paul Felts, records data. Photo: Matt Ellis/NOAA Fisheries

His attraction to the mysteries of the deep and the written word has resulted in many discoveries, including a critical role in the discovery of a new species, the Carolina hammerhead (Sphryna gilberti). Recently, Trey’s research has focused on, among other things, examining the movement patterns of sharks. However, understanding the movement patterns of sharks is tricky. Many have large ranges and occupy numerous habitats under the surface of the ocean that covers over 70% of our planet. Most sharks can’t be kept in captivity. For all these reasons and more, sharks are mysterious and fascinating creatures.

So which sharks are currently catching Trey’s attention? One of his many interests is a group of bonnethead (Sphyrna tiburo) sharks that have been recaptured over multiple summers in specific estuaries in South Carolina.

Like other hammerhead sharks, the bonnethead shark has a cephalofoil. Why do hammerheads look like that?

The photo of this bonnethead shark was taken in 2010 by a fellow TAS, Bruce Taterka, also aboard the Oregon II.

Theories abound about the funny looking hammerheads, whose heads look more like wings than hammers. As Trey says, many people have speculated “the hammerhead has a cephalofoil because ….” giving a single reason. Some say the cephalofoil acts as a dive plane, pulling the shark up or down as it swims, others say the distance between the nostrils allows it to smell better, honing in on prey, some say it is to compensate for their blind spot, and still others hypothesize that the shark uses its head to pin down prey.

Many people have asked this question, but very few get to work like Trey does, collecting data, making observations, and analyzing the data. He says the best part of his job is “when I figure something out that no one else knows.” One day, looking at data a friend collected in Bull’s Bay estuary, near Charleston, South Carolina, he noticed a pattern of the same sharks getting recaptured there year after year. A small group of different aged, different size friends going to enjoy their summer together to Bull’s Bay while another group always going to the North Edisto estuary every year? Why?

Trey hypothesizes that in the summer, blue crab abound in that spot, and are thick with eggs. The bonnetheads have the shortest gestation period of all sharks, four months, and need a lot of nutrients. Their heads, shaped just right for holding down a blue crab, and their convergence at Bull’s Bay on the fertile female crabs, may just be the elements necessary to get a shark pup from embryo to viability. Pretty cool!

Here, a juvenile bonnethead shark is being measured. Photo: NOAA Fisheries

With all this evidence supporting a hypotheses that the bonnethead shark cephalofoil is used for holding down prey, one might predict that Trey’s next publication on the topic will make that conclusion.

“People want to pick one answer,” Trey says, but “there is a lot more that we don’t know than we do.” There is often more than one right answer, he continues, more than one solution to a problem. Speaking about fishing regulation, conservationists and fishermen, Trey suggests that both sides need to understand that the other side has positive things to contribute. He lives his life this way, moving fluidly among the deck crew, officers, stewards, and scientists looking for commonalities. Together, all the members of the team play an essential role in keeping the ship and survey moving forward.

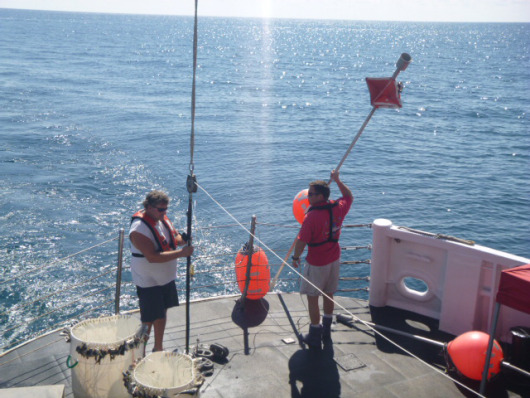

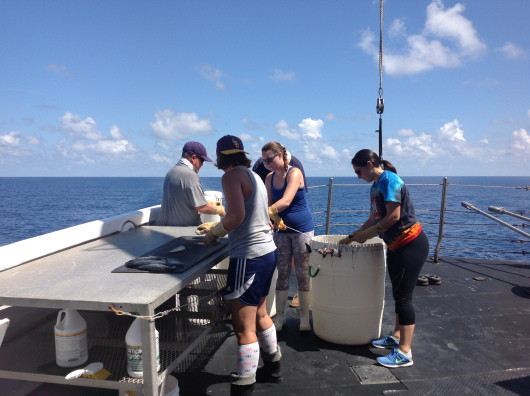

Kevin, Matt Ellis, NOAA Science Writer, Paul, and Trey were the four other members of the day shift science team. I took my christened baiting gloves home with me as a souvenir.

Personal Log

Each member of the crew shared insights and skills that I will take back to my classroom and incorporate into my life.

My work as a NOAA Teacher at Sea was one of the most challenging experiences of my life. I knew very little about fish before stepping aboard the Oregon II, and from the crew have gained understanding of and appreciation for fish, other marine species, and the diversity of life on our planet. I’ve learned that while the Gulf of Mexico is home to the world’s largest fisheries, the human impact from industries, watershed runoff, development, and other sources is unbelievable.

When the time for science arrives, or weaves its way into the other subjects as it always does, students’ eyes light up. I know I am far from a professional scientist, but through NOAA, I can now speak authentically and accurately about what happens in the field and why. My students have become mini-scientists, speaking among themselves about collecting data as if it were a playground game.

As I listened to NOAA Corps Officer David Reymore share memories of a Make a Wish trip with his son to Disneyland, I learned to take each moment with a child as a gift and was also reminded of the sacrifice crew members and their families make in support of science during their weeks, months, and years at sea. Thank you, each and every NOAA crew member aboard the NOAA fleet, for your service. With the time away from family as the only negative, I learned that the many different careers available through NOAA provide great learning opportunities, adventure, and inspiration to those who are ready for some very hard work.

What advice can you give me as a teacher, I ask Trey. “Quote me on this,” he says with a smile, “don’t give kids so much —- homework. Let them be kids.”

NOAA Corps Officer Brian Yannutz wears his lucky shark hat as we bring in the long line.

Laughing, shaking my head in amazement, leafing through my journals, I have enough inspiration from these two weeks to last a lifetime. How did I get so fortunate?