Linda Stone on Maintaining Focus in a Maddeningly Distractive World

As I mentioned a few minutes ago, our new issue (subscribe!) includes a Q-and-A I did with Linda Stone, coiner of the term "continuous partial attention," on how to maintain sanity and focus in an insane and unfocused world.

As I mentioned a few minutes ago, our new issue (subscribe!) includes a Q-and-A I did with Linda Stone, coiner of the term "continuous partial attention," on how to maintain sanity and focus in an insane and unfocused world. Here is the promised extended-play bonus version, beyond what we could work into two pages of the magazine:

___

JAMES FALLOWS: You're well known for the idea of continuous partial attention. Why is this a bad thing?

LINDA STONE: Continuous partial attention is neither good nor bad. We need different attention strategies in different contexts. The way you use your attention when you're writing a story may vary from the way you use your attention when you're driving a car, serving a meal to dinner guests, making love, or riding a bicycle. The important thing for us as humans is to have the capacity to tap the attention strategy that will best serve us in any given moment.

JF: What do you mean by "attention strategy"?

LS: From the time we're born, we're learning and modeling a variety of attention and communication strategies. For example, one parent might put one toy after another in front of the baby until the baby stops crying. Another parent might work with the baby to demonstrate a new way to play with the same toy. These are very different strategies, and they set up a very different way of relating to the world for those children. Adults model attention and communication strategies, and children imitate. In some cases, through sports or crafts or performing arts, children are taught attention strategies. Some of the training might involve managing the breath and emotions---bringing one's body and mind to the same place at the same time.

Self-directed play allows both children and adults to develop a powerful attention strategy, a strategy that I call "relaxed presence." How did you play as a child?

JF: I have two younger siblings very close in age, so I spent time with them. I also just did things on my own, reading and building things and throwing balls and so on.

LS: Let's talk about reading or building things. When you did those things, nobody was giving you an assignment, nobody was telling you what to do--there wasn't any stress around it. You did these things for your own pleasure and joy. As you played, you developed a capacity for attention and for a type of curiosity and experimentation that can happen when you play. You were in the moment, and the moment was unfolding in a natural way.

You were in a state of relaxed presence as you explored your world. At one point, I interviewed a handful of Nobel laureates about their childhood play patterns. They talked about how they expressed their curiosity through experimentation. They enthusiastically described things they built, and how one play experience naturally led into another. In most cases, by the end of the interview, the scientist would say, "This is exactly what I do in my lab today! I'm still playing!"

An unintended and tragic consequence of our metrics for schools is that what we measure causes us to remove self-directed play from the school day. Children's lives are completely programmed, filled with homework, lessons, and other activities.. There is less and less space for the kind of self-directed play that can be a fantastically fertile way for us to develop resilience and a broad set of attention strategies, not to mention a sense of who we are, and what questions captivate us. We have narrowed ourselves in service to the gods of productivity, a type of productivity that is about output and not about results.

JF: When people talk about attention problems in modern society, they usually mean the distractive potential of smartphones and so on. Is that connected to what you're talking about in early-childhood development?

LS: We learn by imitation, from the very start. That's how we're wired. Andrew Meltzoff and Patricia Kuhl, professors at the University of Washington I-LABS, show videos of babies at 42 minutes old, imitating adults. The adult sticks his tongue out. The baby sticks his tongue out, mirroring the adult's behavior. Children are also cued by where a parent focuses attention. The child's gaze follows the mother's gaze. Not long ago, I had brunch with friends who are doctors, and both of them were on call. They were constantly pulling out their smartphones. The focus of their 1-year-old turned to the smartphone: Mommy's got it, Daddy's got it. I want it.

We may think that kids have a natural fascination with phones. Really, children have a fascination with what-ever Mom and Dad find fascinating. If they are fascinated by the flowers coming up in the yard, that's what the children are going to find fascinating. And if Mom and Dad can't put down the device with the screen, the child is going to think, That's where it's all at, that's where I need to be! I interviewed kids between the ages of 7 and 12 about this. They said things like "My mom should make eye contact with me when she talks to me" and "I used to watch TV with my dad, but now he has his iPad, and I watch by myself."

Kids learn empathy in part through eye contact and gaze. If kids are learning empathy through eye contact, and our eye contact is with devices, they will miss out on empathy.

JF: What you're describing sounds like a society-wide autism.

LS: In my opinion, it's more serious than autism. Many autistic kids are profoundly sensitive, and look away [from people] because full stimulation overwhelms them. What we're doing now is modeling a primary relationship with screens, and a lack of eye contact with people. It ultimately can feed the development of a kind of sociopathy and psychopathy.

JF: I'm afraid to ask, but is this just going to get worse?

LS: I don't think so. You and I, as we grew up, experienced our parents operating in certain ways, and may have created a mental checklist: Okay, my mom and dad do that, and that's cool. I'll do that with my kids, too. Or: My mom and dad do this, and it's less cool, so I'm not going to do that when I'm a grown-up.

The generation that has been tethered to devices serves as a cautionary example to the next generation, which may decide this is not a satisfying way to live. A couple years ago, after a fire in my house, I had a couple students coming to help me. One of them was Gen X and one was a Millennial. If the Gen Xer's phone rang or if she got a text, she would say "I'm going to take this, I'll be back in a minute." With the Millennial, she would just text back "L8r." When I talked to the Millennial about it, she said, "When I'm with someone, I want to be with that person." I am reminded of this new thing they're doing in Silicon Valley where every-one sticks their phone in the middle of the table, and whoever grabs their phone first has to treat to the meal.

JF: So people may yet find ways to "disconnect"?

LS: There is an increasingly heated conversation around "disconnecting." I'm not sure this is a helpful conversation . When we discuss disconnecting, it puts the machines at the center of everything. What if, instead, we put humans at the center of the conversation, and talk about with what or whom we want to connect?

Talking about what we want to connect with gives us a direction and something positive to do. Talking about disconnecting leaves us feeling shamed and stressed. Instead of going toward something, the language is all about going away from something that we feel we don't adequately control. It's like a dieter constantly saying to him or herself, "I can't eat the cookie. I can't eat the cookie," instead of saying, "That apple looks delicious."

JF: You say that people can create a sense of relaxed presence for themselves. How?

LS: When we learn how to play a sport or an instrument; how to dance or sing; or even how to fly a plane, we learn how to breathe and how to sit or stand in a way that supports a state of relaxed presence. My hunch is that when you're flying, you're aware of everything around you, and yet you're also relaxed. When you're water-skiing, you're paying attention, and if you're too tense, you'll fall. All of these activities help us cultivate our capacity for relaxed presence. Mind and body in the same place at the same time.

People have become increasingly drawn to meditation and yoga as a way to cultivate relaxed presence. Any of these activities, from self-directed play to sports and performing arts, to meditation and yoga, can contribute cultivating relaxed presence.

In this state of relaxed presence, our minds and bodies are in the same place at the same time and we have a more open relationship with the world around us.

Another bonus comes with this state of relaxed presence. It's where we rendezvous with luck. A U.K. psychologist ran experiments in which he divided self-described lucky and unlucky people into different groups and had each group execute the same task. In one experiment, subjects were told to go to a café, order coffee, return and report on their experience.

The self-described lucky person found money on the ground on the way into the café, had a pleasant conversation with the person they sat next to at the counter, and left with a connection and potential business deal. The self-described unlucky person missed the money - it was left in the same place for all experimental subjects to find, ordered coffee, didn't speak to a soul, and left the café. One of these subjects was focused in a more stressed way on the task at hand. The other was in a state of relaxed presence, executing the assignment.

We all have a capacity for relaxed presence, empathy, and luck. We stress about being distracted, needing to focus, and needing to disconnect. What if, instead, we cultivated our capacity for relaxed presence and actually, really connected, to each moment and to each other?

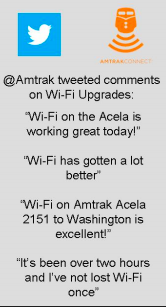

1) Amtrak suddenly has much better Wi-Fi service on some routes -- starting with the Acela I am taking right now from DC to NY. Of course I admit that griping about the speed and reliability of a (free) Wi-Fi service, on a moving train, epitomizes having too few real problems to gripe about. But until recently the service really had been so slow and unreliable that I wished Amtrak would not even advertise it. That way, people who got any connection at all would feel lucky, rather than people expecting connections staring in frustration at their screens.

1) Amtrak suddenly has much better Wi-Fi service on some routes -- starting with the Acela I am taking right now from DC to NY. Of course I admit that griping about the speed and reliability of a (free) Wi-Fi service, on a moving train, epitomizes having too few real problems to gripe about. But until recently the service really had been so slow and unreliable that I wished Amtrak would not even advertise it. That way, people who got any connection at all would feel lucky, rather than people expecting connections staring in frustration at their screens.

With one exception: the guy they cast as President of the United States (right) just is not plausible in that role. No offense to the actor, Michael Gill. I assume he's doing what the director wants. But real-life presidents, whatever their oddities and limitations, display some edge of seriousness, intensity, cunning that lets you understand how they got where they are. Even ones that don't start out that way unavoidably become different and weightier-seeming people in office -- in part because of the nonstop flow of choices only they can make. You see a similar transformation in the character of Raymond Tusk in the final episodes of House of Cards. At first, he is an amiable sage of the prairie. Then, you see the edge.

With one exception: the guy they cast as President of the United States (right) just is not plausible in that role. No offense to the actor, Michael Gill. I assume he's doing what the director wants. But real-life presidents, whatever their oddities and limitations, display some edge of seriousness, intensity, cunning that lets you understand how they got where they are. Even ones that don't start out that way unavoidably become different and weightier-seeming people in office -- in part because of the nonstop flow of choices only they can make. You see a similar transformation in the character of Raymond Tusk in the final episodes of House of Cards. At first, he is an amiable sage of the prairie. Then, you see the edge.

-thumb-620x1129-121918.png)

I don't know which interpretation is worse: that the WSJ editorialist doesn't see what is dishonest and preposterous in this passage -- or that he or she does, and doesn't care. These lines

I don't know which interpretation is worse: that the WSJ editorialist doesn't see what is dishonest and preposterous in this passage -- or that he or she does, and doesn't care. These lines

The central message of that post was: the Chinese people are worse than their system. As I pointed out in linking to it, my view has been the reverse: "Even though a thousand aspects of modern Chinese life drive me crazy, I still can't help liking the openness, the vim, the life of most of the people I meet here. That is, I find it easier to get along with the people than with the whole system." For instance, see a moment from one of my early visits to the Qingdao Beer Festival, at right.

The central message of that post was: the Chinese people are worse than their system. As I pointed out in linking to it, my view has been the reverse: "Even though a thousand aspects of modern Chinese life drive me crazy, I still can't help liking the openness, the vim, the life of most of the people I meet here. That is, I find it easier to get along with the people than with the whole system." For instance, see a moment from one of my early visits to the Qingdao Beer Festival, at right.