skip

navigation  |

800-411-3222 (Español)

Predator Control for Sustainable and Organic Livestock Production |

| By NCAT Staff Published 2002 ATTRA Publication #IP196 |

The

printable PDF version of the entire document is available

at: http://attra.ncat.org/attra-pub/PDF/predator.pdf 16 pages — 644K Download Acrobat Reader |

Abstract

This publication examines how to identify livestock predators and how to control them. Many species of animals can be classified as predators, but coyotes and dogs account for more than three-quarters of all livestock lost to predators. This publication focuses primarily on the control of coyotes and dogs through management practices, such as fencing and secure areas, and the use of guard animals, such as dogs, donkeys, and llamas.

Table of Contents

IntroductionIt is virtually impossible to eliminate all predators and the damage they cause to livestock, but good management can reduce this damage and still be consistent with sustainable or organic livestock production. Because every farm is different, there is no single practice or single combination of practices that will be right for every situation. Therefore, when predators strike, it is important to be aware of all options available for their control and to act at once. Writing in the Ontario (Canada) Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs publication Management Practices Can Influence Predation, Anita O'Brien says:

All species of livestock are susceptible to predation, especially young animals, but sheep and goats suffer most. Therefore, while the information here is applicable to all livestock, it is directed especially toward protecting sheep and goats. Identifying Predator Attacks

Livestock can die or disappear for many reasons—predators, disease, poisonous plants, bloat, exposure, theft, stillbirth—and even clear evidence that a predator has been feeding on a carcass is not evidence that the predator was the killer, because most predators will scavenge on dead livestock. (2) The best proof that a predator has been at work—and the best means of identifying it—is when a large animal has been attacked and is largely intact, although the disappearance of young animals may also be a sign of predator activity. Predation can have a devastating effect not only on livestock but on the livelihood of the farmer as well. According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) report Sheep and Goat Predator Loss, U.S. sheep and lamb losses to predators totaled 273,000 animals in 1999. As you can see from Table 1 below, coyotes and dogs caused more than 75 percent of those losses. This represented more than one-third of the total losses of sheep and lambs from all causes and resulted in a cost to farmers of more than $16 million. (3)

According to Something's Been Killing My Sheep—But What? How to Differentiate Between Coyote and Dog Predation, a publication of the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, predation has risen rapidly during the past 10 to 15 years, causing ever-increasing losses to sheep operations. Ontario producers reported almost three times more sheep lost in 1995 (3,060) than in 1986 (1,149). The total would have been higher, the publication states, if losses to dogs—both feral and domestic—and unexplained disappearances had been included. (4) Once a carcass has begun to decompose or has been scavenged, it's often hard to determine whether the animal was killed by a predator or died of other causes. To differentiate between the two, it's necessary to examine the overall appearance of the carcass, including the condition of the coat, the eyes, ears, and feces (firm or diarrheic), even the position of the animal in death (animals that have died of natural causes are usually found on their sides or on their chests with their legs folded under them). (5) Although the pattern of killing typical of a predator species can sometimes help identify the problem predator, an individual's killing style can overlap the killing style of another species. Other types of evidence, such as tracks and feces, are sometimes necessary to correctly identify the kind of predator responsible. (2) The Wildlife Services (WS) of the USDA/Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is the federal agency to contact with livestock predation problems. They work with farmers and ranchers to protect agricultural resources in a way that is practical, humane, effective, and environmentally sound. They can help you identify predators and offer remedies that will minimize the impact on wildlife. (6) Each state's Wildlife Service activity report, along with the state WS contact information, is available at the Wildlife Service Web site. An excellent publication, Procedures for Evaluating Predation on Livestock and Wildlife, provides details on many of the observations that are needed to determine whether a predator is the cause of livestock death. It also provides specific information on the typical killing patterns for most of the predator species. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage—1994 has separate chapters on more than 90 species of wildlife that may cause damage to crops or livestock. Each of these chapters covers identification, damage-prevention, and control. The 90 species-chapters are listed alphabetically. The book is also available on CD-ROM or in paper copy. The 36-page Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development publication Methods of Investigating Predation of Livestock outlines how to tell whether a predator killed an animal and how to identify the predator. (See Further Resources Books, for ordering information). The Maryland Small Ruminant Web page "Predator and wildlife management" is a rich source of information, with links to many different sites and publications covering all areas of predator-damage control and management. Coyotes and dogs as predatorsWhen stock is killed or missing, it is most likely that the predator responsible is either a coyote or a dog. The NASS Sheep and Lambs Predator Loss table shown above reveals that in 1999 coyotes and dogs caused more than 75 percent of all predator losses for sheep, with losses to coyotes alone topping 60 percent. Coyotes have become a problem in almost all of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The state Wildlife Service can verify the legal status of coyotes in your state; contact information is available at the Wildlife Services Web site. Most states allow coyotes to be shot or trapped at any time, if they are causing damage, but some states have different regulations or specific hunting seasons only.

In some cases, a producer may have difficulty trying to decide whether a coyote, a neighbor's dog, or their own dog was the killer. The Ontario publication Something's Been Killing My Sheep—But What? How to Differentiate Between Coyote and Dog Predation lists ten criteria that can help determine the culprit. They are: time of attack; duration of attack; temperament of flock; extent of attack or kill; location of attack or carcasses; target animals; attacking behavior; feeding behavior; tracks at site; and droppings. (4) Some of the criteria used to distinguish between coyote and dog predation are:

The 31-page Alberta book Coyote Predation of Livestock provides information to help producers prevent or reduce losses from coyotes. (See Further Resources: Books, for ordering information.) If a dog or pack of dogs is the culprit, what can the producer do? The Ontario publication Family Dogs Attack Sheep cites an Australian study of 1,400 dogs that attacked livestock. In the study, the authorities used trained tracking dogs to follow the offending dogs home. The authorities found that most of the dog owners would not believe that their dogs had attacked the livestock. Most of the owners believed that their dogs were either too small, young, or friendly to commit such an act. None-the-less, the publication states:

Owners should understand the reason why a dog attacks sheep—it's all for the love of the game. (7) Dr. C. V. Ross, in his book Sheep Production and Management, suggests that livestock producers learn their legal rights concerning the control of dogs in their areas. He explains that there is great variation among laws concerning predatory dogs. Livestock owners "have the right to protect their property from damage, but there are all kinds of variations in the interpretation of protecting property and therein lies the basis for many bitter and costly lawsuits." (8) Livestock producers have lost cases in court when they have killed dogs on their property that were not caught in the immediate act of killing livestock. Wolves as predatorsIn states such as Minnesota and Wisconsin where wolves have been reintroduced, producers need to consider the increased challenge of protecting livestock from these adaptable predators. In most states where wolves have been reintroduced, livestock killed by wolves is compensated for by the state, upon presentation of evidence that it was a wolf kill. The publication Wolves in Farm Country: A Guide for Minnesota Farmers and Ranchers Living in Wolf Territory provides information on what to do if a wolf kill is suspected, whom to contact, and how to preserve the evidence. The publication cautions:

The Canadian Federation of Agriculture publication Preventing Wolf Predation on Private Land provides some specific methods to reduce wolf predation, but remember that the wolf is not protected in Canada and that hunting, trapping, and snaring are permitted there. Management Techniques to Minimize Predator LossesAll management techniques have advantages and disadvantages. Some will work for one producer but not for another. It is important for producers to combine the management techniques best suited to their operations with the most effective predator control methods for their circumstances. FencingSpecially constructed woven (mesh) wire or electric fencing can be useful in a management strategy for deterring predators. The USDA/APHIS publication A Producers Guide to Preventing Predation of Livestock states:

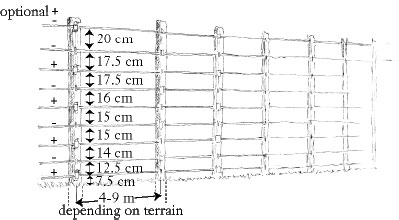

Fencing is most successful if it is strung before the predator has established a pattern of movement. If coyotes have been feeding on livestock in a pasture, the construction of a fence will probably not deter them, since they already recognize the livestock as food. The USDA/APHIS publication Wildlife Services: Helping Producers Manage Predation comments that "because predator exclusion fences may restrict movement of other wild species, especially large game animals, Federal or State regulations may prohibit construction of effective fences in some areas." (10) Building a new mesh or woven wire fence for predator management can be expensive. A properly constructed 5½- to 6-foot mesh wire fence should have horizontal spacing of less than 6 inches and vertical spacing of 2 to 3 inches. It should have barbed wire at ground level and barbed wire, electric wire, or wire overhangs on top to help deter predators that will climb or dig under fences.

Multiple strands of single-wire electric fencing can cost less than new mesh fencing. Seven or nine strands of high-tensile smooth wire, with alternating charged and grounded wires (beginning with a charged bottom wire) can help reduce predation. A Canadian predation study in the mid 1970s showed a 90 percent reduction in sheep lost to predation in pastures with electrified fences. (11) Electric fences require maintenance to ensure proper livestock protection, and snow and frozen ground can greatly reduce the effectiveness of electric fencing. (11) Adding electric wires at the top and electric trip wires to the bottom and middle of a mesh fence that is in good condition can help make it an effective predator barrier and is probably more cost-effective than replacement. An electric trip wire placed about 6 inches off the ground and 8 inches outside the woven wire fence will help prevent predators from digging under it. Electric wires added to the top and at various intervals along the woven wire fence will help discourage predators from climbing or jumping the fence.

Detailed information on building fences is available from the following sources:

Record keepingAccurate records provide a ready way to know when livestock is missing from a pasture. Knowing quickly that a loss has occurred helps speed the response to a predator problem. In addition, knowing the exact number and location of the losses can help to identify the predation pattern and the problem areas on the farm or ranch. (1) Night confinement close to residencesBecause many predators, including coyotes, are usually active between dusk and dawn, confining livestock in predator-proof pens at night can reduce losses. In addition, some predators are reluctant to approach any place where humans are present. Livestock will learn to come to the secure pens when they are regularly penned at night. Additional labor and maintenance of facilities may be required. (12) Lambing in sheds or secure lotsLambing in sheds or secure lots can reduce losses to predators. Shed lambing allows the producer greater access to the sheep to assist with lambing and will also provide the opportunity for lambing earlier in the season. The main disadvantages of shed lambing are the initial cost of the shed and the additional labor needed. (13) Prompt removal of all dead livestockDead animals attract coyotes and other scavenging predators. Unless the dead animals are removed, the predators will return to feed on them. Coyotes may depend on dead animals to remain in livestock-raising areas. (12) One Canadian study found that on farms that promptly removed dead livestock, predator losses were lower than on farms where dead livestock were not removed. (13) See the Appendix for information on various livestock disposal methods. Using larger livestock in rougher pastures with histories of predator problemsPastures with a history of predator problems should be avoided—especially during lambing. Pastures with rough terrain or dense vegetation provide good cover for predators. Placing larger animals in these pastures will usually reduce the incidence of predation. (10) Noise, light, and other deterrentsPredators can display uncanny abilities to outwit a producer's attempts to protect livestock. Producers may need to use more than one practice concurrently, and probably will need to vary the practices occasionally. Most predators are wary of any changes in their territory and will shy away from anything different until they become familiar with it. The following are several devices that help discourage predators.

Guard AnimalsDogs, donkeys, and llamas can all serve as full-time guard animals, but the effectiveness of any of them will also depend on the bonding, training, instincts, and temperament of individual animals. All guard animals require an investment of time and money, and there is no guarantee that they will be successful. Sometimes a single guard animal will not be enough to protect the livestock. Several guard dogs may be necessary to patrol larger areas or to better protect against packs of predators. A llama and guard dog combination can be trained to work cooperatively, but donkeys or llamas will not properly bond to livestock if more than one of their own species is present with the livestock. Rotational grazing can sometimes help, because the livestock are confined to a smaller area, allowing guard animals to be more effective. Producers should research the costs and advantages of the various guard animals, and seek advice from other producers in the area with guard animal experience. Producers need to remember that guard animals by themselves will probably not be successful without implementation of other predator control methods. No one predator control method will solve every producer's predator problem, but combining several methods can help. The following are good sources of general information on livestock guard animals:

Guard dogsLivestock-guarding dogs originated in Europe and Asia. Most are large (80-120 pounds), mainly white breeds. Guard dogs do not herd sheep; they are full-time members of the flock. They stay with or near the flock most of the time and aggressively protect the sheep. In some instances guard dogs may injure the stock they are guarding or attack other animals, such as pets that enter their territory. They may also confront unfamiliar people (hikers, etc.) who approach the livestock. Producers using guard dogs should post signs to alert passers-by and plan to escort visitors going near the sheep. (17) Neighbors should also be notified that you are using a guard dog, because a patrolling guard dog may be mistaken for a predator dog. Usually, a successful guard dog is a standard guard breed that has been properly reared and trained. But sometimes, despite good breeding and training, a dog just won't guard properly. Many, but not all, of these failures trace back to improper rearing or to the dog being too old to bond with the sheep. Research and surveys indicate that only about three-fourths of guard dogs are temperamentally suited to being good guardians. (17) In order to properly raise the best guard dog, the producer needs to understand what a good guard dog does, assess the temperament of the pup, and raise it correctly. Some key points are:

The nearest office of the USDA/APHIS Wildlife Services (WS) should have additional information about using dogs to guard livestock. State WS contact information is available at the USDA/APHIS Wildlife Services Web site. The USDA/APHIS/WS has two predator prevention publications, Livestock Guarding Dogs Protecting Sheep from Predators (PDF / 11 M) and Helping Producers Manage Predation (PDF / 373 K), as well as a loaner video on using guardian dogs. These free publications and the video are available by contacting:

Additional information about using guardian dogs is also available by contacting any of these USDA/APHIS/WS specialists: Roger A. Woodruff (18), Jim Luchsinger (19), or Jeffrey S. Green. (20) For additional information on livestock guard dogs:

DonkeysDonkeys make good guard animals because they naturally hate dogs and coyotes, are not afraid of them, and like to intimidate them. Donkeys also are social animals that will associate with other species of livestock in the absence of other donkeys; however, it can take a donkey four to six weeks to fully bond with a sheep flock. Because they can eat what the sheep eat, guard donkeys can be low maintenance; however, it is also important to feed the donkey something at the same time the sheep are fed. This will help the donkey understand that if it stays by the flock it will not miss a meal. Do not overfeed the donkey or let it become overweight. Never feed the donkey away from the flock; you want the donkey to stay always with the flock. (21) It is very important that donkeys do not receive any feed that contains Rumensin, Bovatec, urea, or other products intended only for ruminant animals, as they can be poisonous to single-stomached animals like donkeys. Donkeys need routine veterinary care, such as hoof trimming, teeth filing, and parasite management. Hoof care is very important, and all donkeys need to be trained to accept hoof trimming. Some additional guard donkey guidelines are:

Additional information on using guard donkeys is available from the following sources:

Llamas

Llamas are aggressive toward coyotes and dogs. When they spot a predator or intruder, most llamas give a warning call, walk or run toward the intruder, and then begin to chase, kick, and paw at it. Llamas are easy to handle, can usually be trained in a few days, and have a high success rate. Once a llama is attached to the sheep and area, the area and sheep become the llama's territory and family. The llama becomes an active leader and protector. Llamas often play with lambs. Llamas seem to bond with cattle as well as they bond with sheep and goats. (21) Llamas with long hair may need shearing occasionally. Llamas that have bonded with humans by bottle-feeding or excessive handling may not make good guard animals. (22) Although llamas are good guardians against single coyotes and some other predators, they (like other guard animals) can be killed by packs of coyotes or dogs, or even a single neighborhood dog that is not intimidated by the guard animal's aggressive attitude. If the llama's aggressive attitude is not sufficient to scare off the predator, the llama may become prey itself, because it is about as defenseless as the animals it is guarding. Good fencing is a must to help llamas better protect themselves, but even that may not be enough in all circumstances. (23) In a 1990-91 Iowa State University study (24), researchers interviewed 145 sheep producers throughout the United States who were using guard llamas. The study looked at the characteristics of guard llamas and at their husbandry. Some of the report's results are:

The Web site Llamapaedia is another good source of general management, maintenance, and other practical information about llamas. Two Llamapaedia publications on guard llamas are: Sheep Guarding and Guarding Behavior. Multispecies grazingDr. Dean M. Anderson at the USDA Jornada Experiment Range (JER) in New Mexico has been working on using bonding between cattle and sheep to create what is called a "flerd," a bonded herd of cattle and flock of sheep for free-ranging conditions. The flerd is created by pen bonding a small group of around 7 weaned lambs of the same gender with 3 non-aggressive or non-abusive heifers or cows for about a month and a half or two months. The pen bonding process conditions the sheep to bond with the cattle and stay close to the cattle when they are foraging in the pasture, rather than forming two separate groups. When a threat appears, the bonded sheep run among the cattle and stay there until the threat is over. (When a threat appears, non-bonded sheep bunch together and stay independent of the cattle.) The number and size of the cattle apparently protects bonded sheep. The bonding seems to work only one-way, with the sheep changing their behavior, and the cattle seeming just to tolerate the presence of the sheep. (25) Pen confinement to establish bonding can be incorporated into other management strategies such as pen lambing or winter feeding. When pen bonding is initiated, it is important to have a safe area where the sheep can escape if the cattle become aggressive. During the first day of bonding, the sheep should be confined in a safe area with the cattle on the other side. After the first day the sheep should be allowed into the cattle area to begin eating and socializing together. The sheep's location in the pen can highlight problems; sheep with abusive cattle will spend twice as much time in the safe area as sheep with non-abusive cattle. Dr. Anderson's research suggests that penning recently weaned lambs or kids with docile, gentle cattle for a minimum of 40 to 50 consecutive days of uninterrupted confinement can result in a consistent bond. Dr. Anderson is attempting to find ways to reduce the necessary bonding time. (25)

Besides predator protection, bonded flerds provide the benefits of multi-species grazing. Grazing both species together makes a better use of the forage in the pasture. Anderson recommends "sheep-proof" boundary fences but adds that "sheep-proof" internal fencing is not necessary for the flerd, because the sheep consistently remain with the cattle during both foraging and resting. Flerds are not limited to sheep and cattle. Dr. Anderson has also bonded 5-month-old mohair kids and 100-day-old Spanish kids with cattle. Some of the Spanish kids demonstrated few flocking tendencies, but Dr. Anderson considers it possible to create a Spanish goat flerd by selecting only animals that stay with the flerd, and eliminating any that refuse. The mohair kids seemed to flock readily and to bond well with both the cattle and the sheep. (25) For additional information on bonding cattle, sheep, and/or goats, contact

References

Further ResourcesWeb sites

National Association of State Departments of Agriculture

Alberta Agriculture, Food, and Rural Development Ministry

Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

Iowa State University

Minnesota Department of Agriculture

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Oregon State University

American Donkey and Mule Society, Inc.

Livestock and Poultry Environmental Stewardship

Books...May Safely Graze: Protecting Livestock Against Predators

Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage Handbook-1994

Coyote Predation of Livestock-Agdex 684-19 Fencing with Electricity-Agdex 724-6 Methods of Investigating Predation of Livestock-Agdex 684-14

Ain't Life Grand with a Great Pyrenees Guarding the Flock

Appendix: Disposal of Dead LivestockRegulations for disposal of livestock mortalities vary from state to state. Most states require timely disposal of mortalities, usually within 24 to 48 hours. A state's Department of Agriculture is usually in charge of regulations concerning the allowable methods of disposal, including incineration, burying, rendering, and/or composting. Producers should contact their local Extension Agent or their Department of Agriculture (Department of Health in Arkansas) for specific regulations and requirements. The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture has each state's contact information listed in a directory located at Incineration of the carcass is one disposal method. Incinerators can be expensive to buy and operate, and their capacity is generally limited to smaller animals. Some incinerators may generate air pollution and objectionable odors. Incinerators are not very practical for small or mid-size livestock producers, if other disposal methods are available. Burial is a common practice and is generally regulated by the state. The livestock carcass usually needs to be buried 4 to 8 feet deep, and the possible problem of contamination leaching into the ground water needs to be considered. Handling animal mortalities by burial in the winter with the ground frozen can also pose problems. Scavengers can uncover improperly buried mortalities. Renderers' pickup services vary greatly from one area to another. Renderer pickup, if available, may be costly and be limited to certain quantities and/or species (sheep and goats are usually not picked up because of concerns about scrapie infection). (1a) Composting livestock carcasses may also be regulated by the state; some states do not allow sheep or goat composting because of concerns about scrapie. If composting is allowed, producers should consider it because composting is cost effective, environmentally sound, and relatively easy. Composting dead animals is achieved by layering the carcasses and the organic waste amendments according to a prescribed plan and not mixing the materials until the composting has finished and the dead animals are fully decomposed (longer time for larger carcasses). Compost piles that are properly constructed and correctly covered with compost mixed to capture odors will not attract scavengers. However, fencing should be used around compost piles to keep out predators and dogs. The Natural Resource, Agriculture and Engineering Service (NRAES) has two excellent publications on composting that provide specific mortality composting guidelines. They are On-Farm Composting Handbook, NRAES-54 for $25 plus postage, and the Field Guide to On-Farm Composting, NRAES-114 for $14 plus postage. They can be ordered at 607-255-7654 or at www.nraes.org. Other sources of information on composting livestock carcasses are:

Appendix Reference:1a) Stanford, K., et al. 2000. Composting as a means of disposal of sheep mortalities. Compost Science and Utilization. Spring. p. 13-146.

Predator Control for Sustainable and Organic Livestock Production

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Site Map | Comments | Disclaimer | Privacy Policy | Webmaster Copyright © NCAT 1997-2009. All Rights Reserved. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||