Start Preamble

Start Printed Page 51114

AGENCY:

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, DHS.

ACTION:

Notice of proposed rulemaking.

SUMMARY:

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) proposes to prescribe how it determines whether an alien is inadmissible to the United States under section 212(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) because he or she is likely at any time to become a public charge. Aliens who seek adjustment of status or a visa, or who are applicants for admission, must establish that they are not likely at any time to become a public charge, unless Congress has expressly exempted them from this ground of inadmissibility or has otherwise permitted them to seek a waiver of inadmissibility. Moreover, DHS proposes to require all aliens seeking an extension of stay or change of status to demonstrate that they have not received, are not currently receiving, nor are likely to receive, public benefits as defined in the proposed rule.

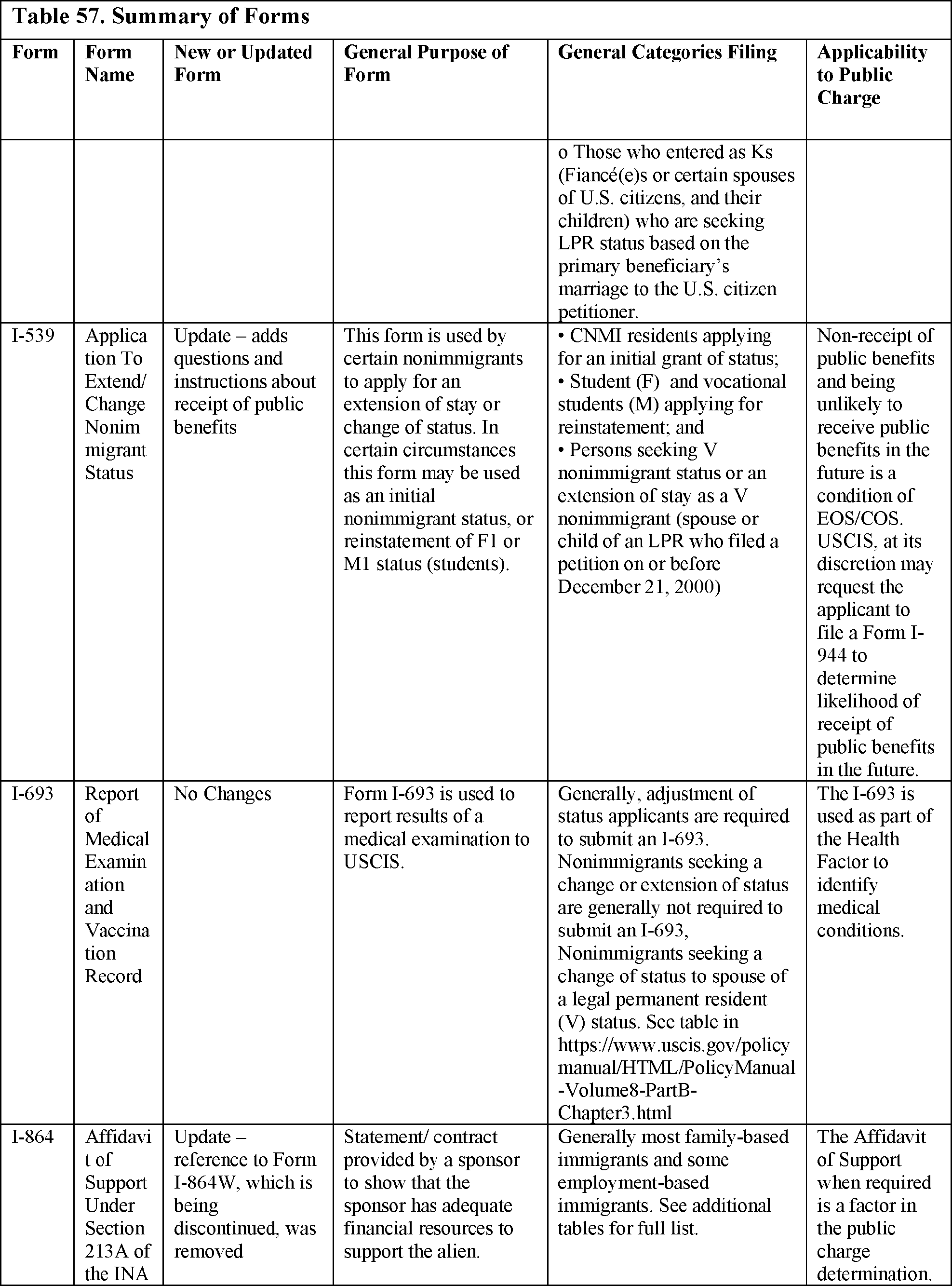

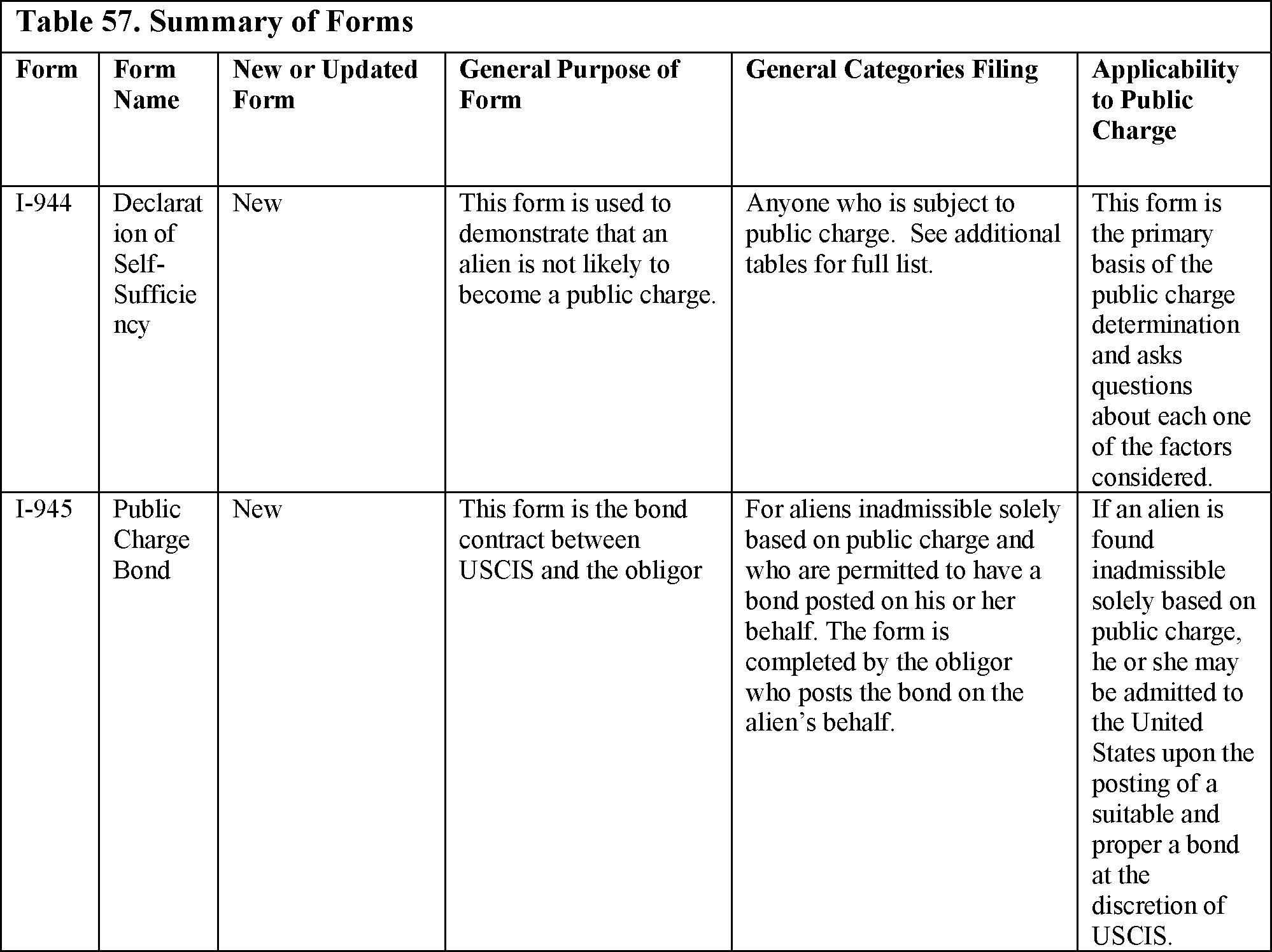

DHS proposes to define “public charge” as the term is used in sections 212(a)(4) of the Act. DHS also proposes to define the types of public benefits that are considered in public charge inadmissibility determinations. DHS would consider an alien's receipt of public benefits when such receipt is above the applicable threshold(s) proposed by DHS, either in terms of dollar value or duration of receipt. DHS proposes to clarify that it will make public charge inadmissibility determinations based on consideration of the factors set forth in section 212(a)(4) and in the totality of an alien's circumstances. DHS also proposes to clarify when an alien seeking adjustment of status, who is inadmissible under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, may be granted adjustment of status in the discretion of DHS upon the giving of a public charge bond. DHS is also proposing revisions to existing USCIS information collections and new information collection instruments to accompany the proposed regulatory changes. With the publication of this proposed rule, DHS withdraws the proposed regulation on public charge that the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) published on May 26, 1999.

DATES:

Written comments and related material to this proposed rule, including the proposed information collections, must be received to the online docket via www.regulations.gov, or to the mail address listed in the ADDRESSES section below, on or before December 10, 2018.

ADDRESSES:

You may submit comments on this proposed rule, including the proposed information collection requirements, identified by DHS Docket No. USCIS-2010-0012, by any one of the following methods:

-

Federal eRulemaking Portal (preferred): www.regulations.gov. Follow the website instructions for submitting comments.

-

Mail: Samantha Deshommes, Chief, Regulatory Coordination Division, Office of Policy and Strategy, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security, 20 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20529-2140. To ensure proper handling, please reference DHS Docket No. USCIS-2010-0012 in your correspondence. Mail must be postmarked by the comment submission deadline.

Start Further Info

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT:

Mark Phillips, Residence and Naturalization Division Chief, Office of Policy and Strategy, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security, 20 Massachusetts NW, Washington, DC 20529-2140; telephone 202-272-8377.

End Further Info

End Preamble

Start Supplemental Information

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION:

Table of Contents

I. Public Participation

II. Executive Summary

A. Major Provisions of the Regulatory Action

B. Costs and Benefits

III. Purpose of the Proposed Rule

A. Self-Sufficiency

B. Public Charge Inadmissibility Determinations

IV. Background

A. Legal Authority

B. Immigration to the United States

C. Extension of Stay and Change of Status

D. Public Charge Inadmissibility

1. Public Laws and Case Law

2. Public Benefits Under PRWORA

(a) Qualified Aliens

(b) Public Benefits Exempt Under PRWORA

3. Changes Under IIRIRA

4. INS 1999 Interim Field Guidance

E. Public Charge Bond

V. Discussion of Proposed Rule

A. Applicability, Exemptions, and Waivers

1. Applicants for Admission

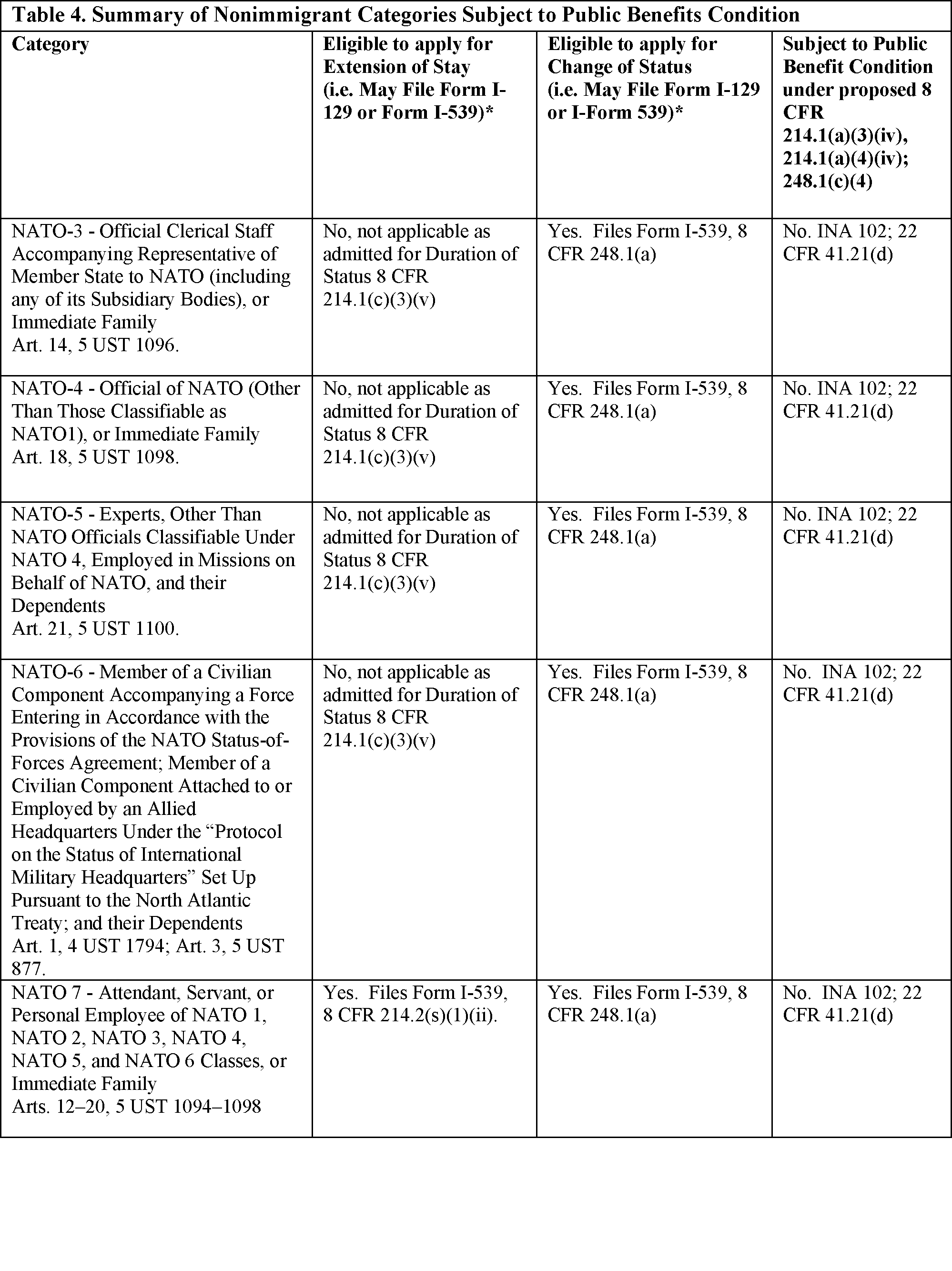

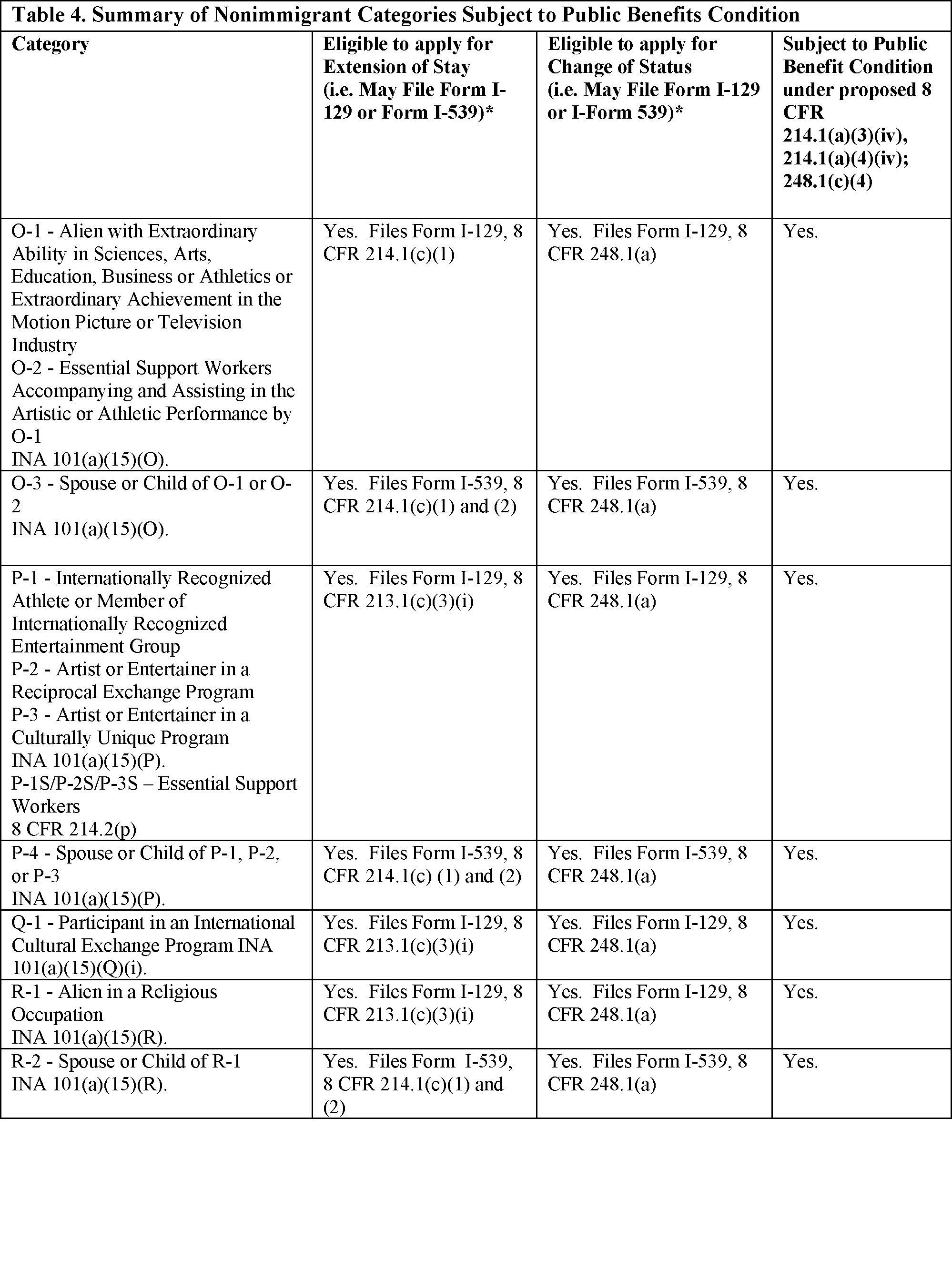

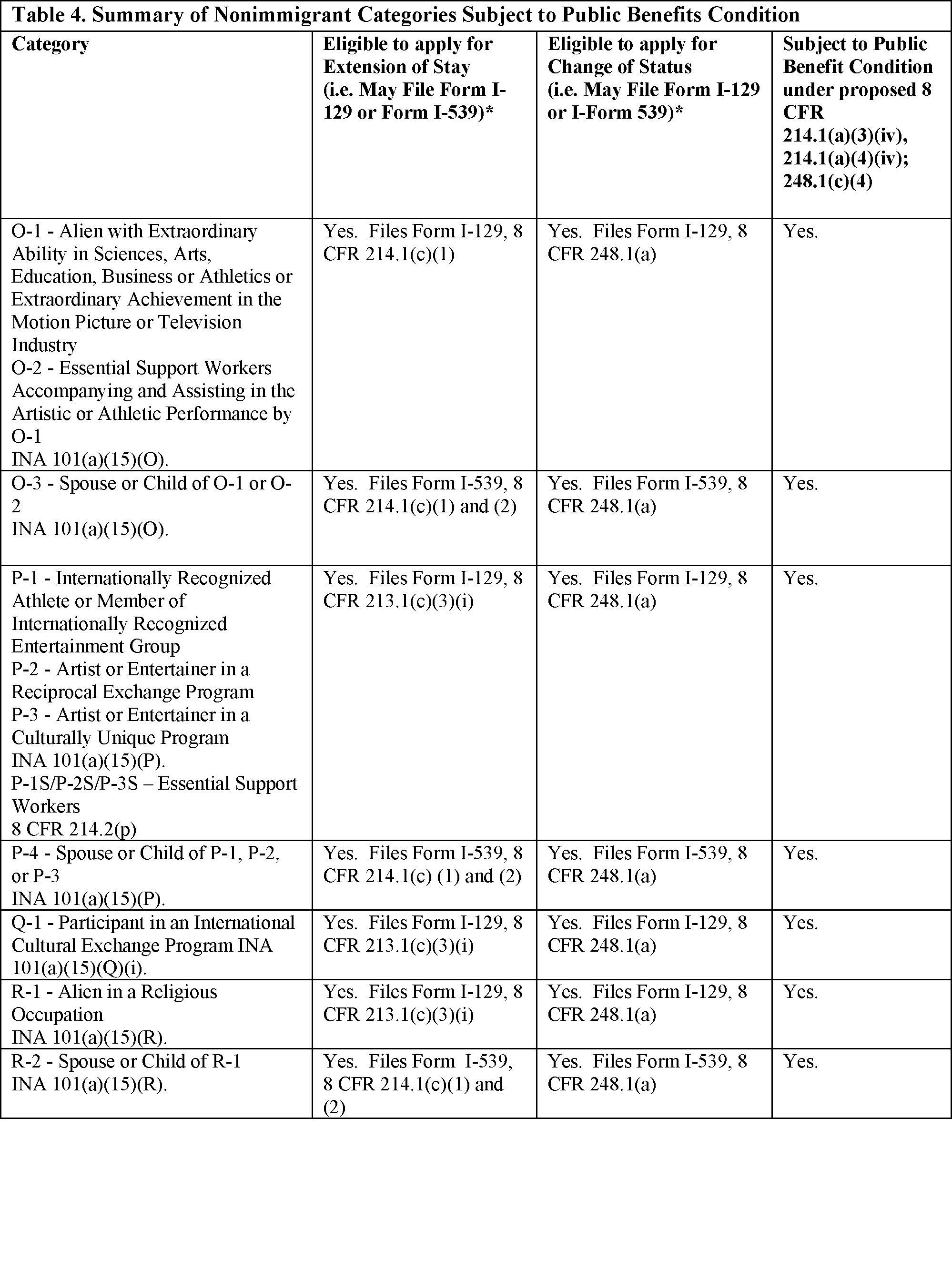

2. Extension of Stay and Change of Status Applicants

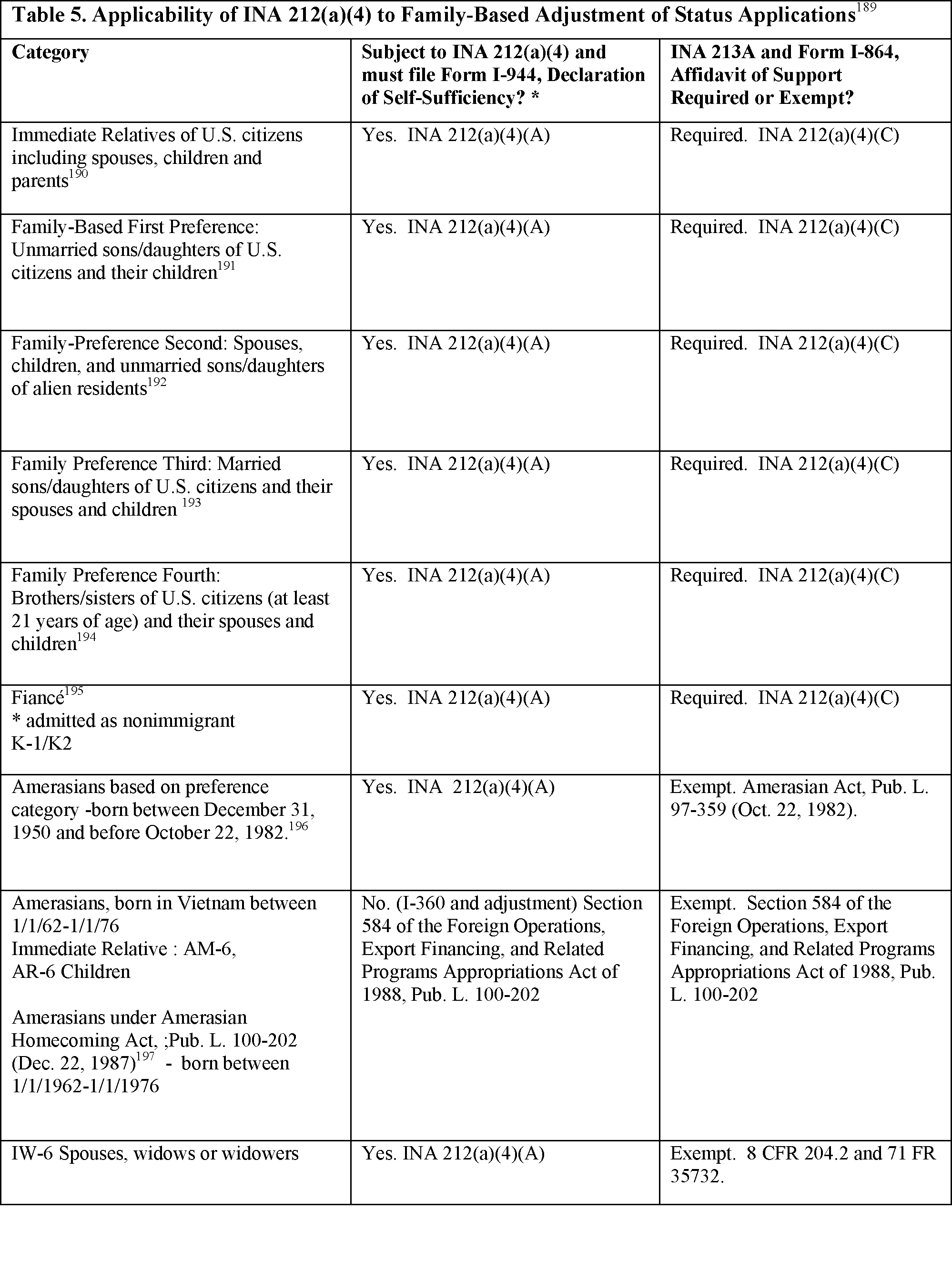

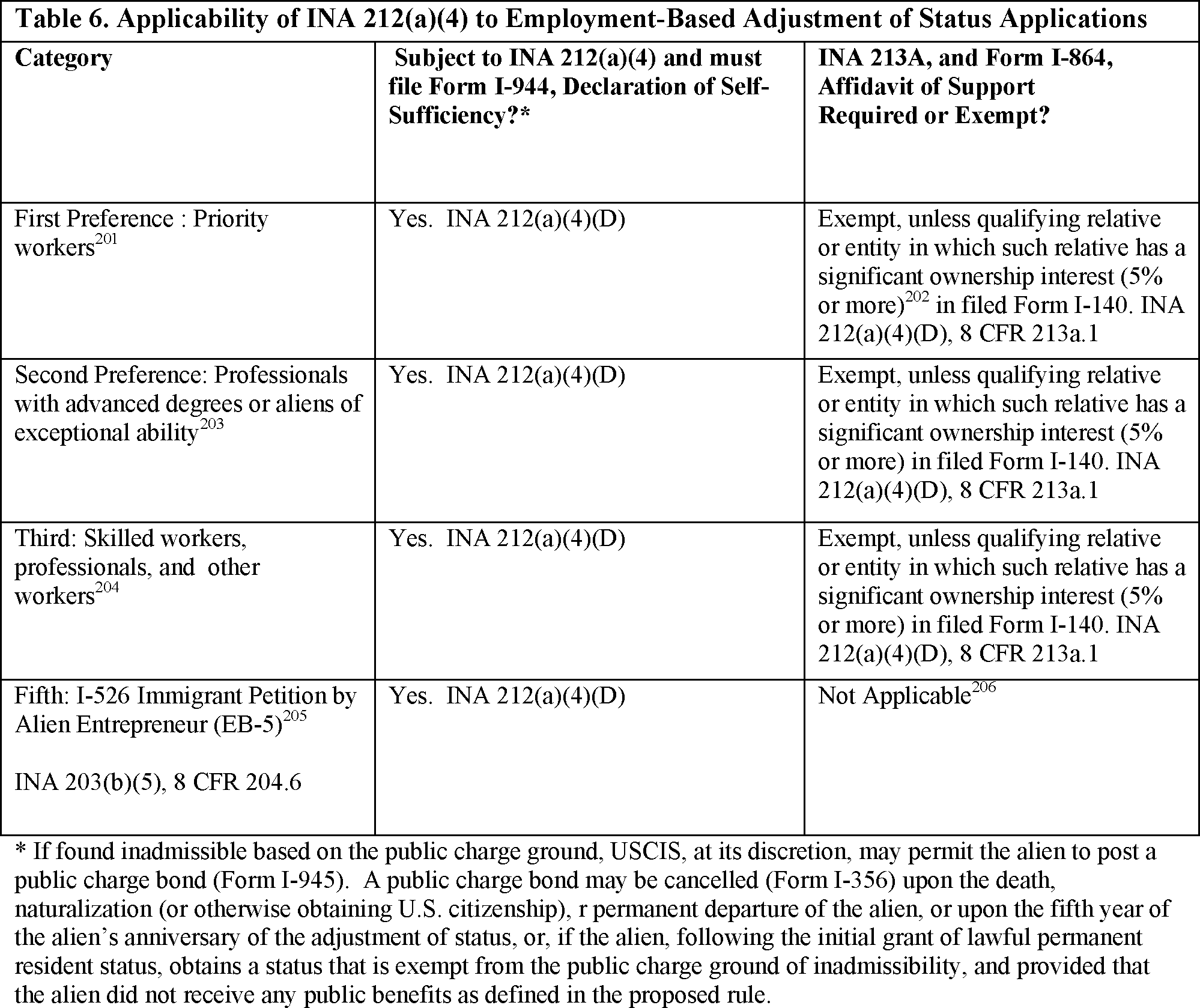

3. Adjustment of Status Applicants

4. Exemptions

5. Waivers

B. Definition of Public Charge and Related Terms

1. Public Charge

2. Public Benefit

(a) Types of Public Benefits

(b) Consideration of Monetizable and Non-Monetizable Public Benefits

i. “Primarily Dependent” Standard and Its Limitations

ii. Fifteen Percent of Federal Poverty Guidelines (FPG) Standard for Monetizable Benefits

iii. Twelve Month Standard for Non-Monetizable Benefits

iv. Combination of Monetizable Benefits Under 15 Percent of FPG and One or More Non-Monetizable Benefits

(c) Monetizable Public Benefits

i. Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

ii. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

iii. General Assistance Cash Benefits

iv. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) v. Housing Programs

a. Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program

b. Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance

(d) Non-Monetizable Public Benefits

i. Medicaid

a. Description of Program

b. Exceptions for Certain Medicaid Services

c. Exception for Receipt of Medicaid by Foreign-Born Children of U.S. Citizens

ii. Institutionalization for Long-Term Care

iii. Premium and Cost Sharing Subsidies Under Medicare Part D

iv. Subsidized Public Housing

(e) Receipt of Public Benefits by Active Duty and Reserve Servicemembers and Their Families

(f) Unenumerated Benefits

(g) Request for Comment Regarding the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP)

(h) Request for Comment Regarding Public Benefit Receipt by Certain Alien Children

(i) Request for Comment Regarding Potential Modifications by Public Benefit Granting Agencies

3. Likely at Any Time To Become a Public Charge

4. Household

(a) Definition of Household in Public Charge Context

(b) Definitions of “Household” and Similar Concepts in Other Public Benefits Contexts

(c) Definitions of Household and Similar Concepts in Other Immigration Contexts

C. Public Charge Inadmissibility Determination

1. Absence of a Required Affidavit of Support

2. Prospective Determination Based on Totality of Circumstances

D. Age

E. Health

1. USCIS Evidentiary Requirements

2. Potential Effects for Aliens With a Disability, Depending on Individual

F. Family StatusStart Printed Page 51115

G. Assets, Resources, and Financial Status

1. Evidence of Assets and Resources

2. Evidence of Financial Status

(a) Public Benefits

(b) Fee Waivers for Immigration Benefits

(c) Credit Report and Score

(d) Financial Means To Pay for Medical Costs

I. Education and Skills

1. USCIS Evidentiary Requirements

J. Prospective Immigration Status and Expected Period of Admission

K. Affidavit of Support

1. General Consideration of Sponsorship and Affidavits of Support

2. Proposal To Consider Required Affidavits of Support

L. Heavily Weighed Factors

1. Heavily Weighed Negative Factors

(a) Lack of Employability

(b) Current Receipt of One of More Public Benefit

(c) Receipt of Public Benefits Within Last 36 Months of Filing Application

(d) Financial Means To Pay for Medical Costs

(e) Alien Previously Found Inadmissible or Deportable Based on Public Charge

2. Heavily Weighed Positive Factors

(f) Previously Excluded Benefits

M. Summary of Review of Factors in the Totality of the Circumstances

1. Favorable Determination of Admissibility

2. Unfavorable Determination of Admissibility

N. Valuation of Monetizable Benefits

O. Public Charge Bonds for Adjustment of Status Applicants

1. Overview of Immigration Bonds Generally

2. Overview of Public Charge Bonds

(a) Public Charge Bonds

(b) Current and Past Public Charge Bond Procedures

(c) Relationship of the Public Charge Bond to the Affidavit of Support

(d) Summary of Proposed Changes

3. Permission To Post a Public Charge Bond

4. Bond Amount and Submission of a Public Charge Bond

5. Public Charge Bond Substitution

6. Public Charge Bond Cancellation

(a) Conditions

(b) Definition of Permanent Departure

(c) Bond Cancellation for Lawful Permanent Residents After 5 Years and Cancellation if the Alien Obtains an Immigration Status Exempt From Public Charge Grounds of Inadmissibility Following the Initial Grant of Lawful Permanent Resident Status

(d) Request To Cancel the Bond, and Adjudication of the Cancelation Request

(e) Decision and Appeal

7. Breach of a Public Charge Bond and Appeal

(a) Breach Conditions and Adjudication

(b) Decision and Appeal

(c) Consequences of Breach

8. Exhaustion of Administrative Remedies

9. Public Charge Processing Fees

10. Other Technical Changes

11. Concurrent Surety Bond Rulemaking

VI. Statutory and Regulatory Requirements

A. Executive Order 12866 (Regulatory Planning and Review), Executive Order 13563 (Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review), and Executive Order 13771 (Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs)

1. Summary

2. Background and Purpose of the Rule

3. Population

(a) Population Seeking Adjustment of Status

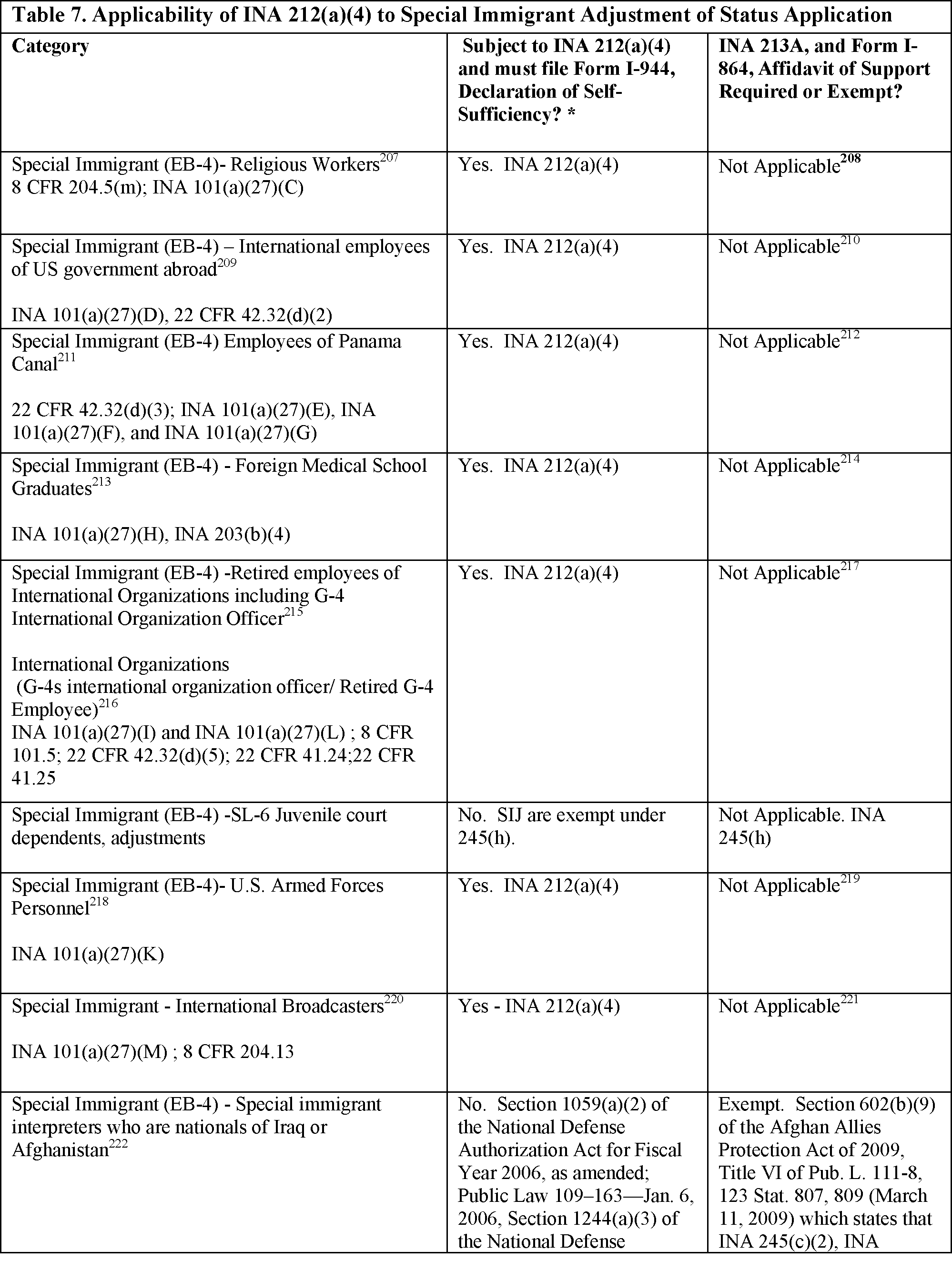

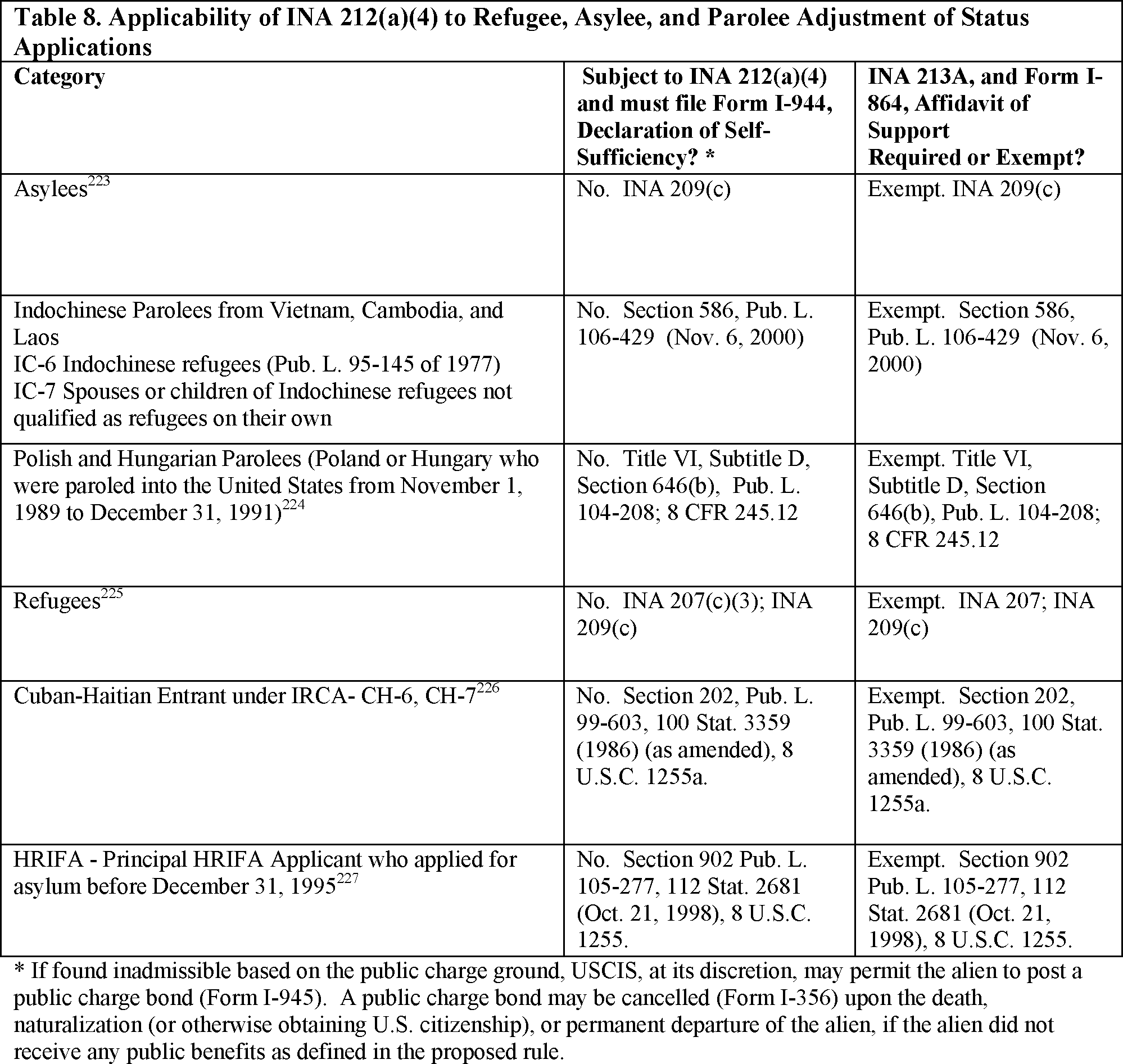

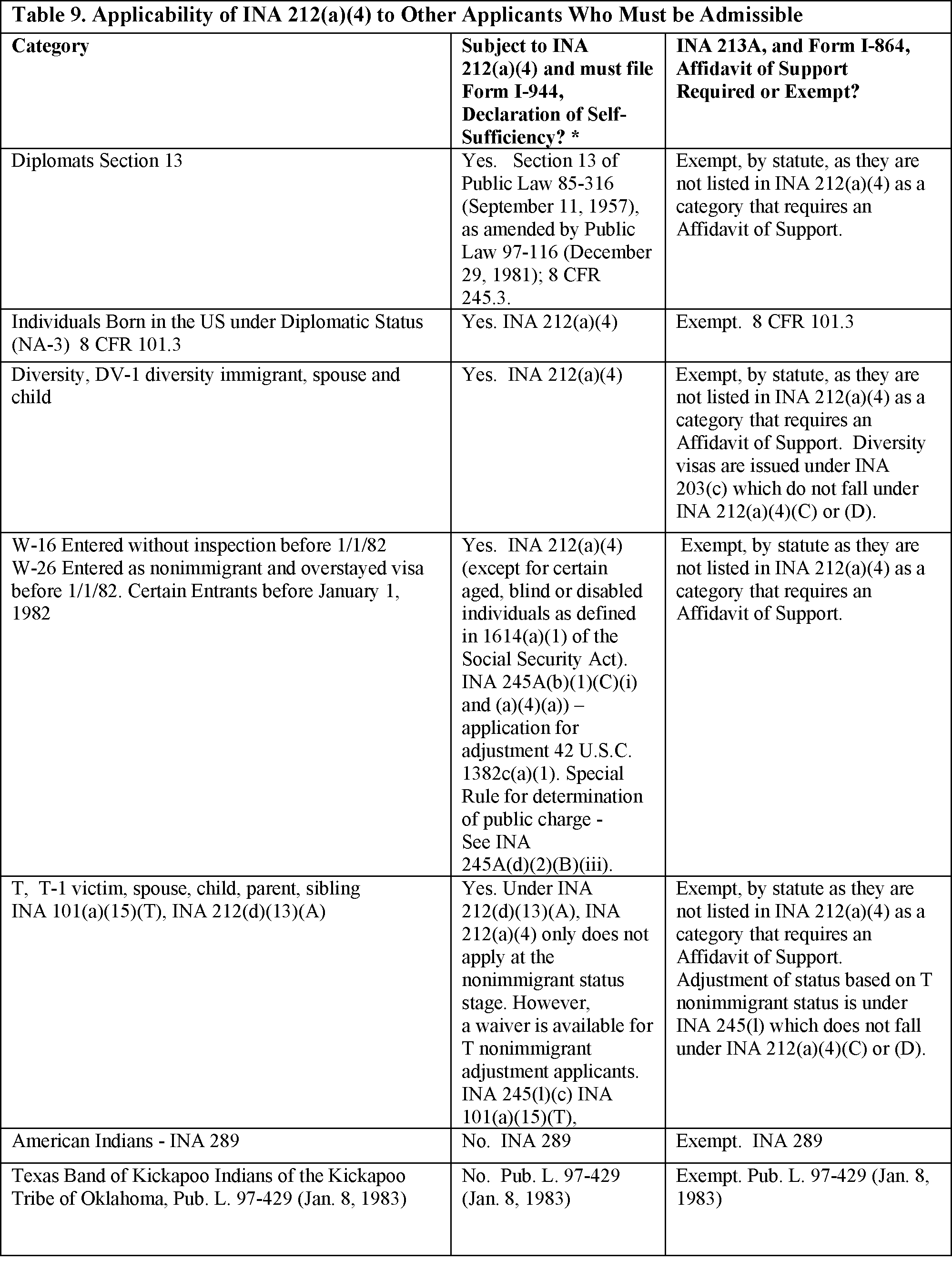

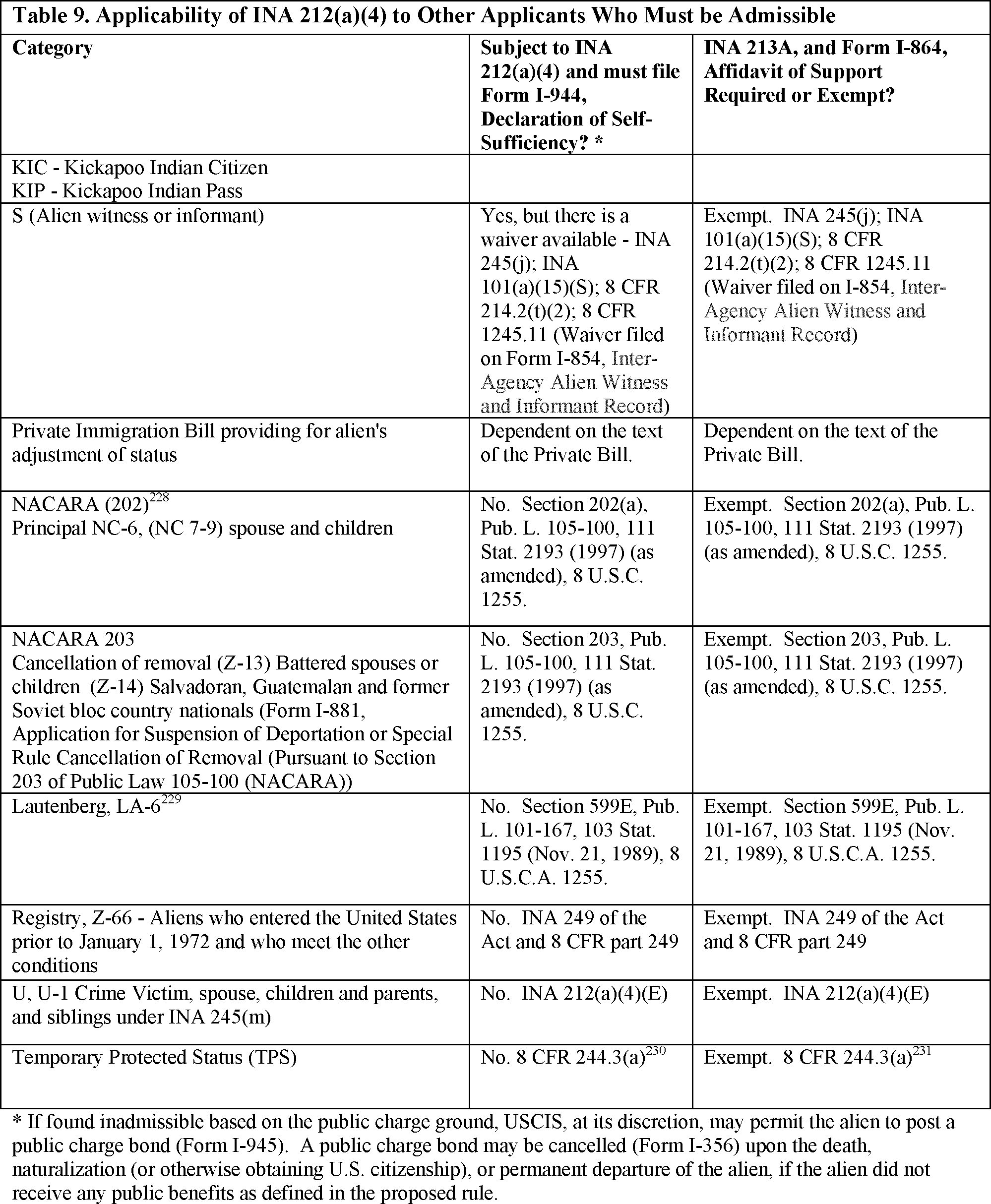

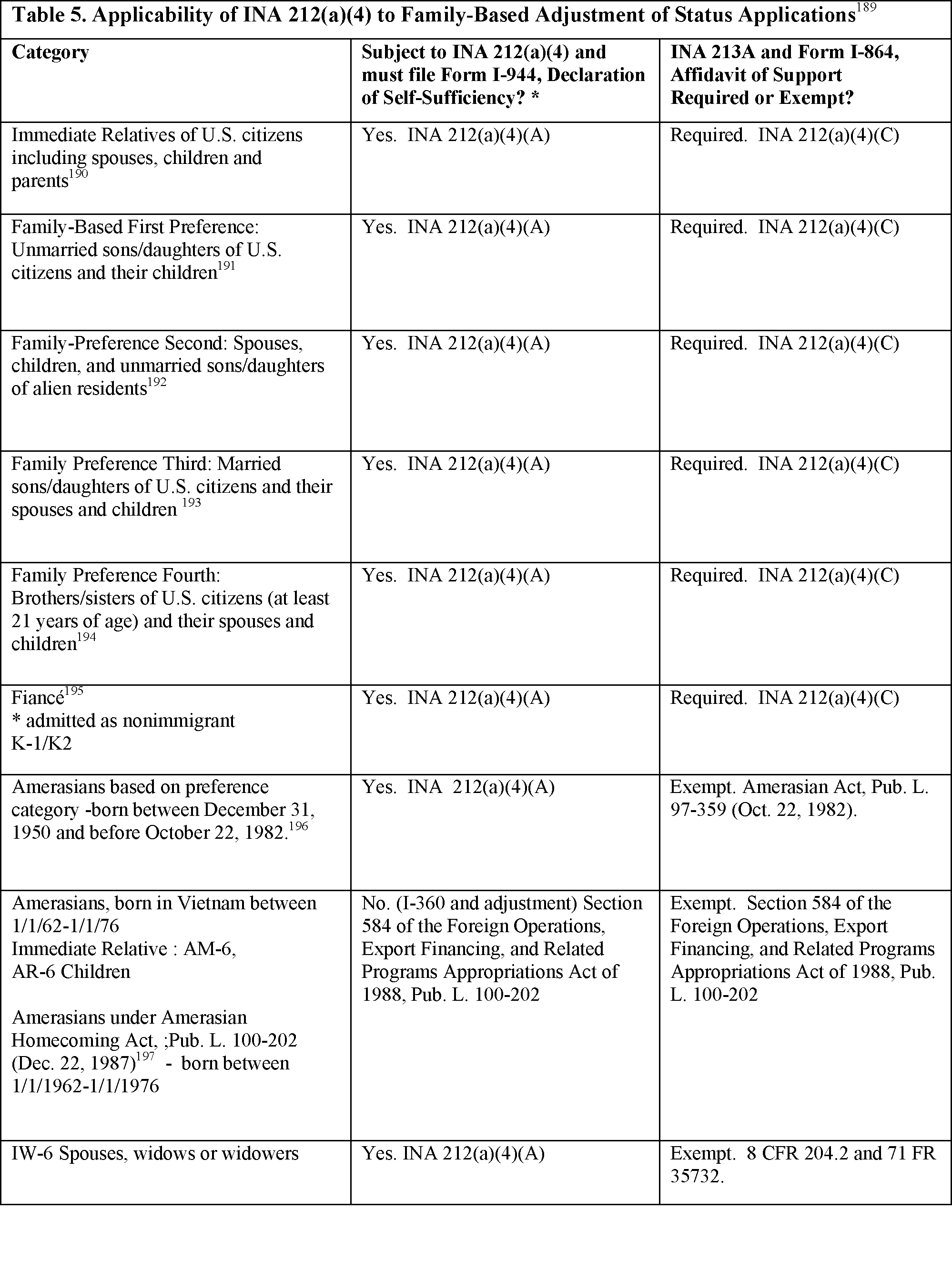

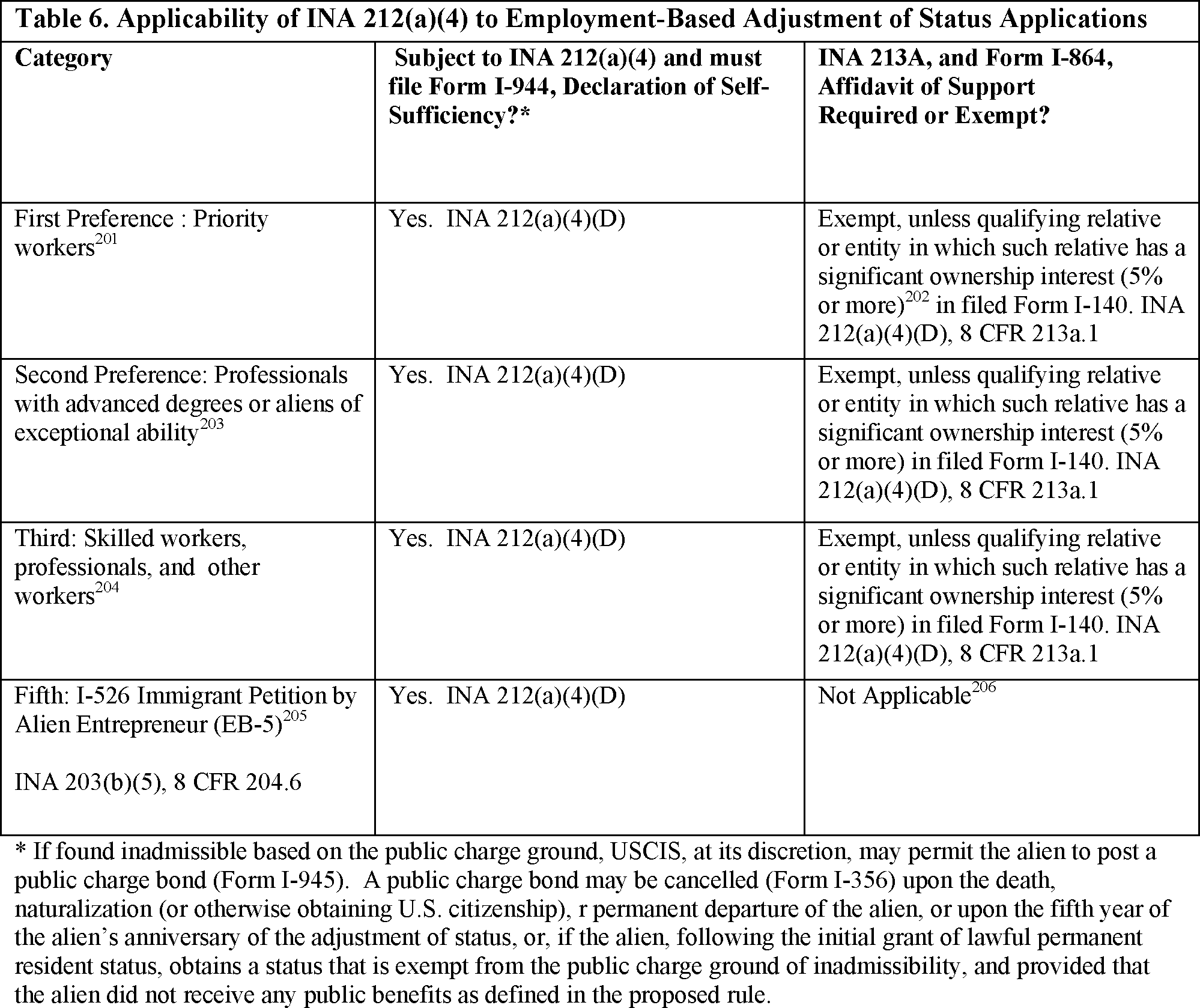

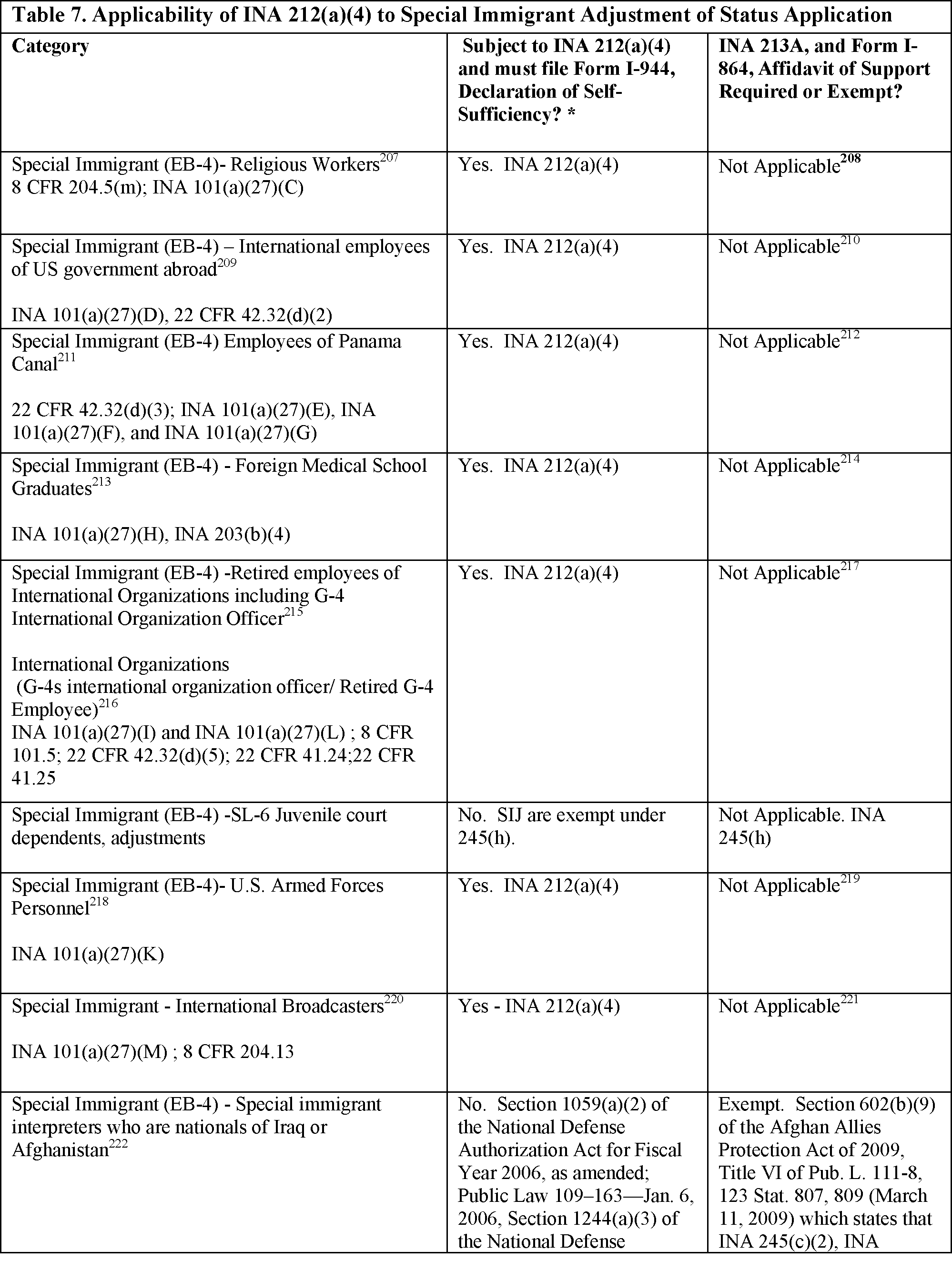

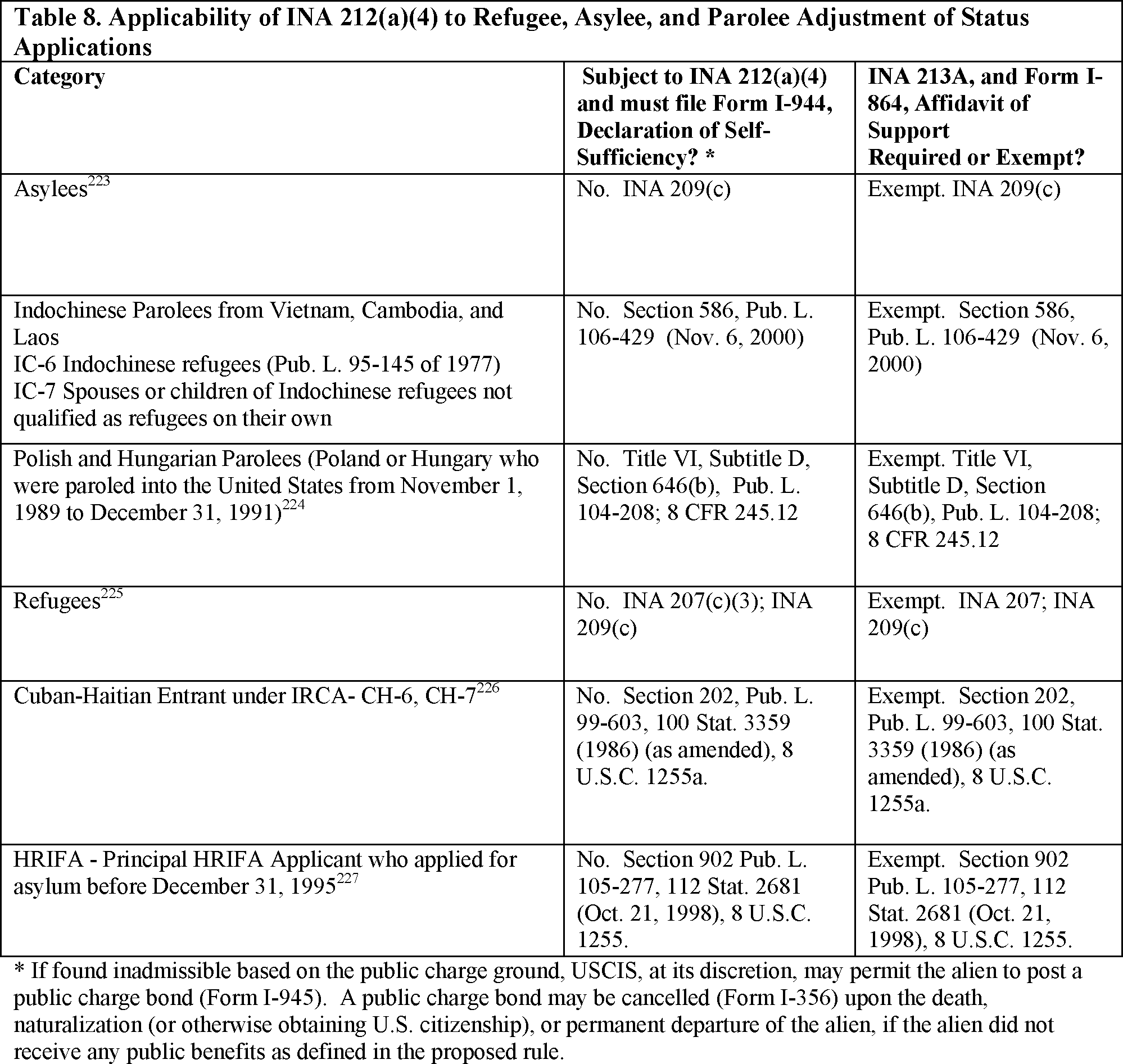

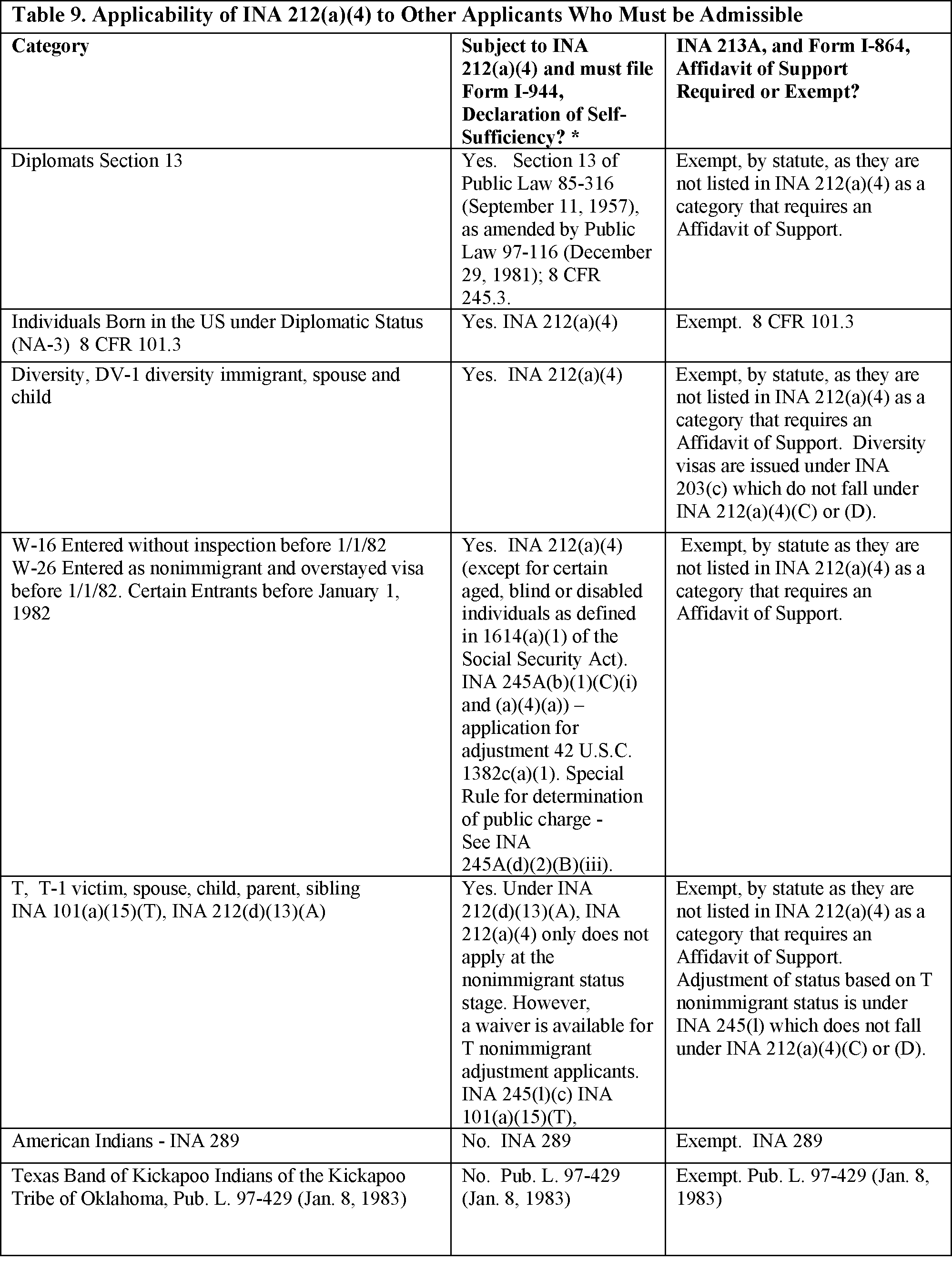

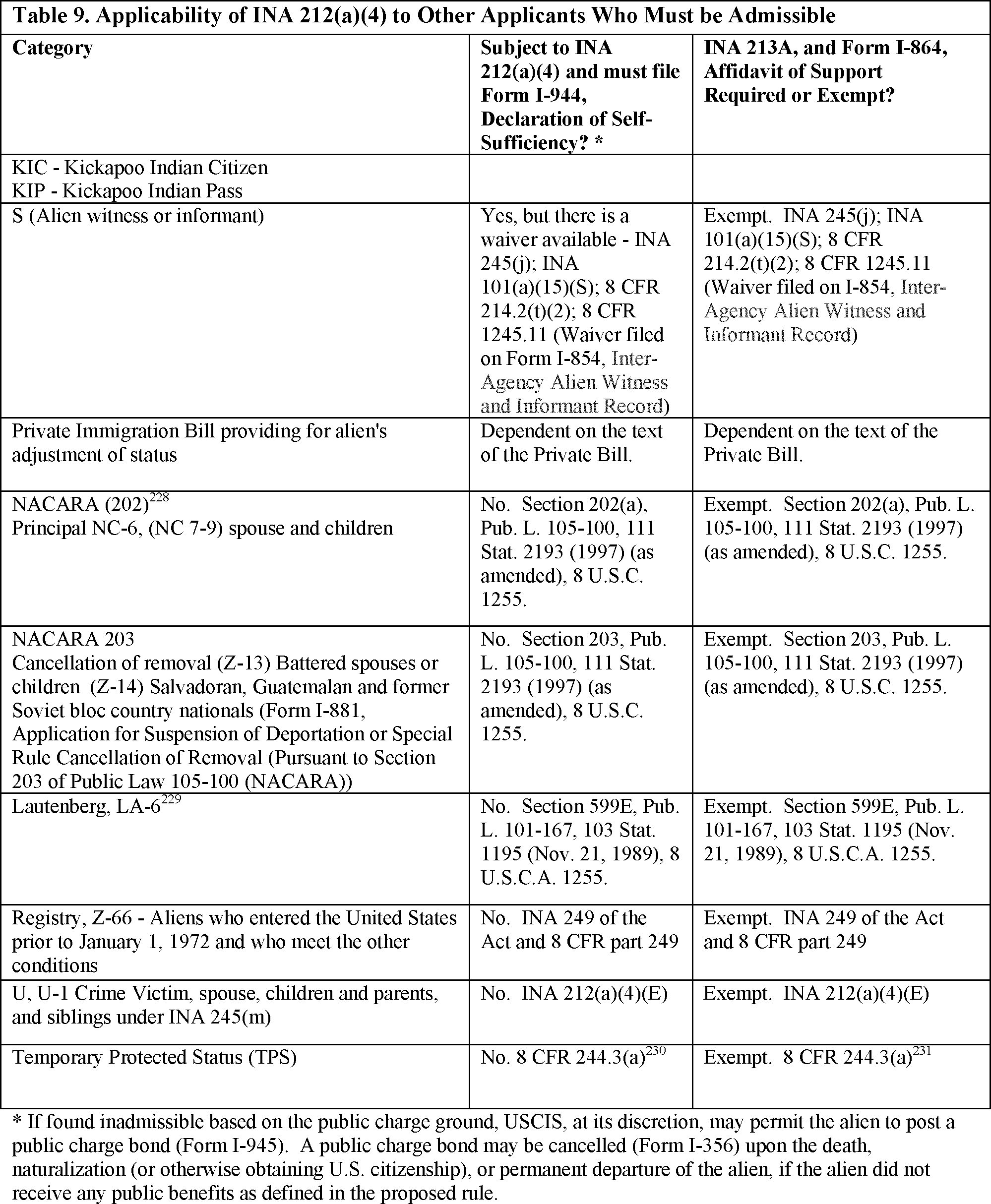

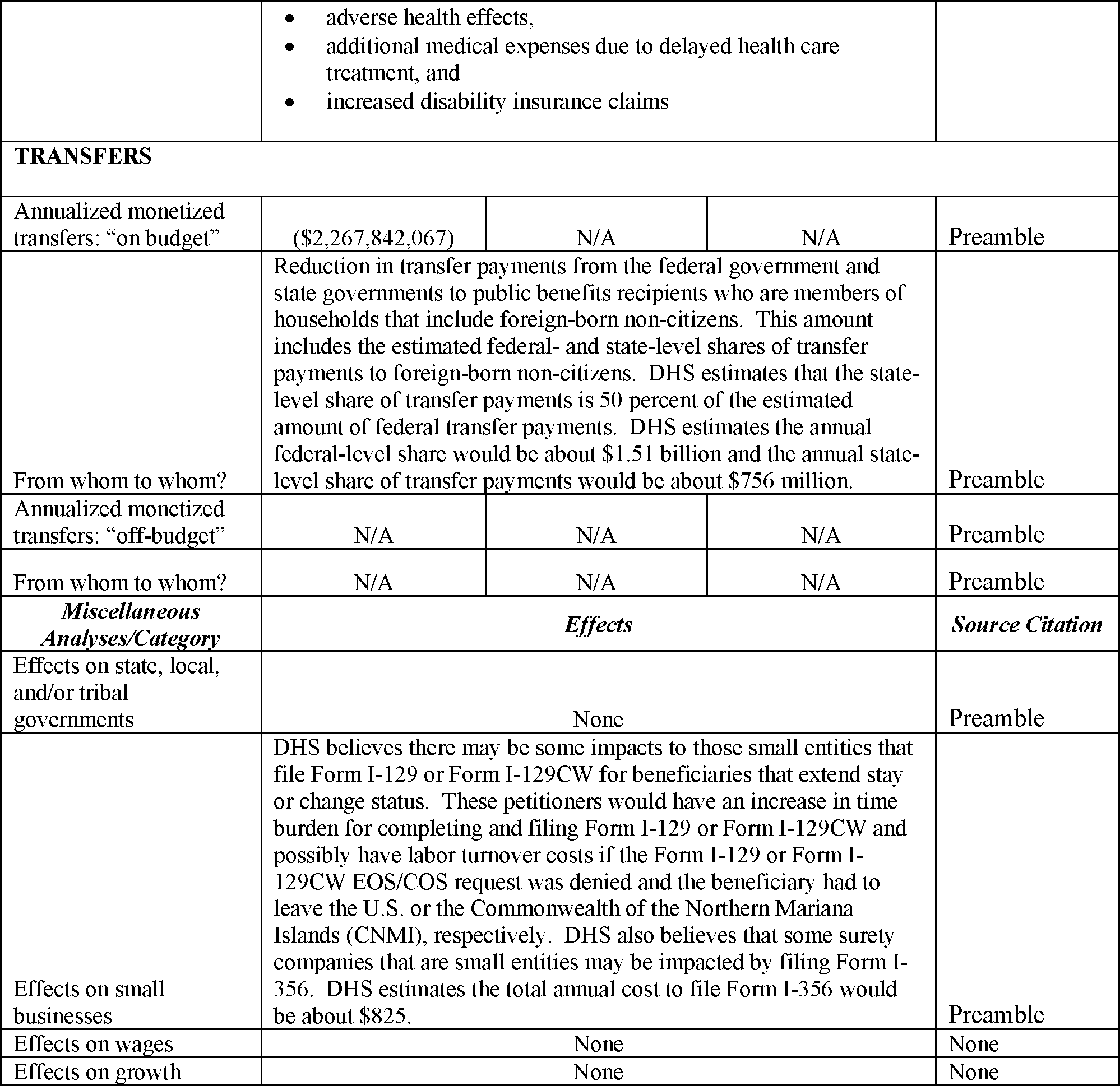

i. Exemptions From Determination of Inadmissibility Based on Public Charge Grounds

ii. Exemptions From the Requirement To Submit an Affidavit of Support

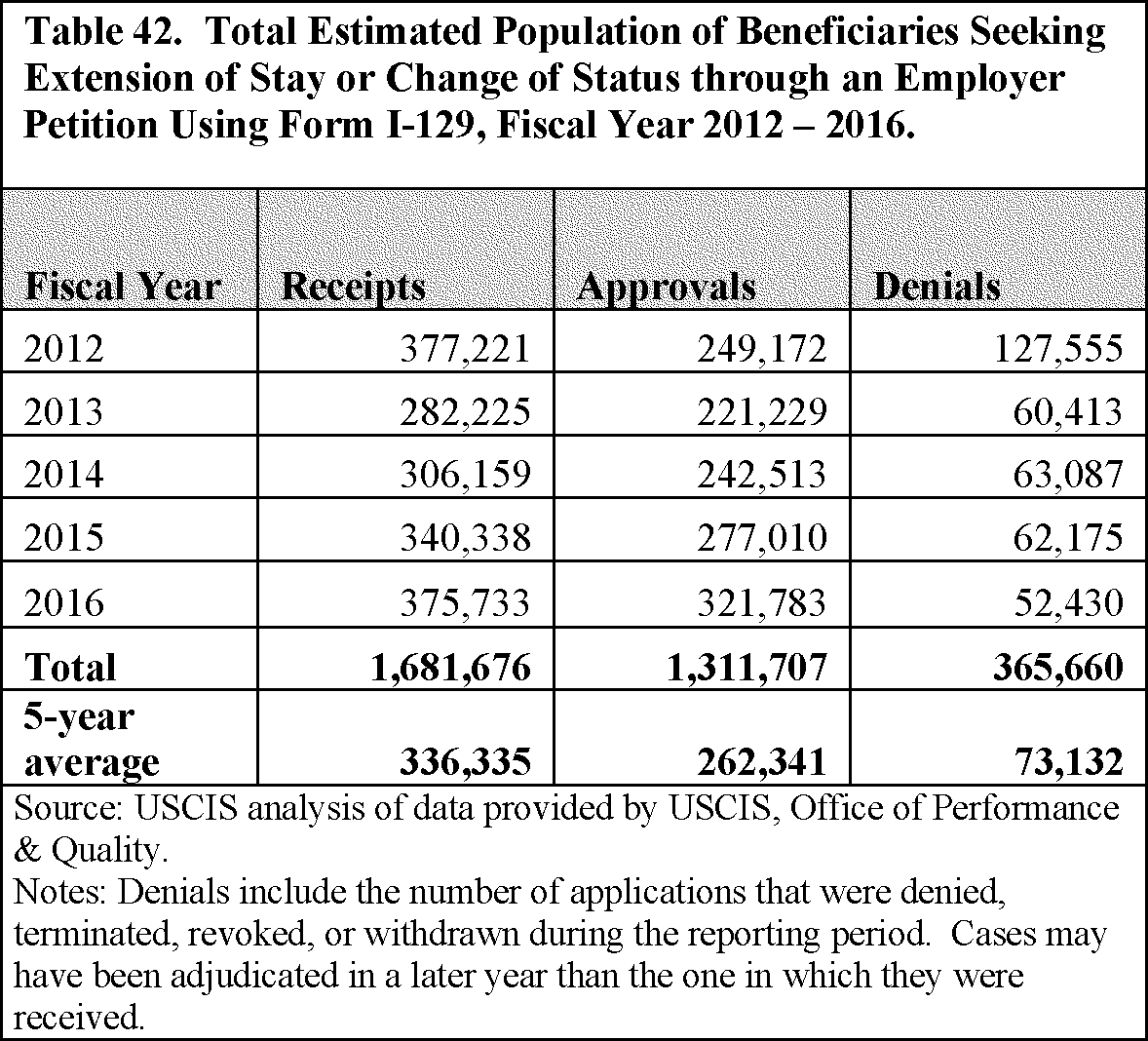

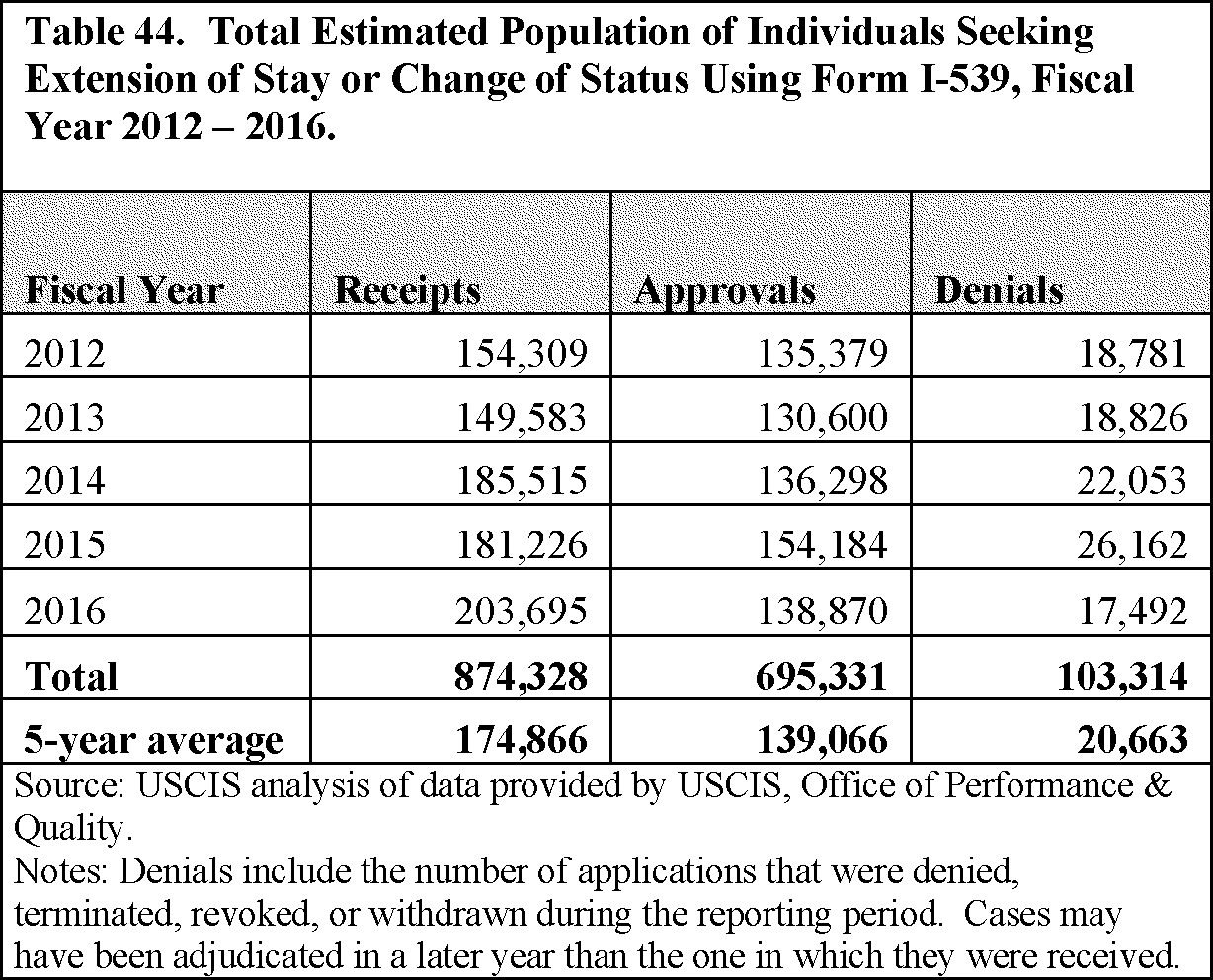

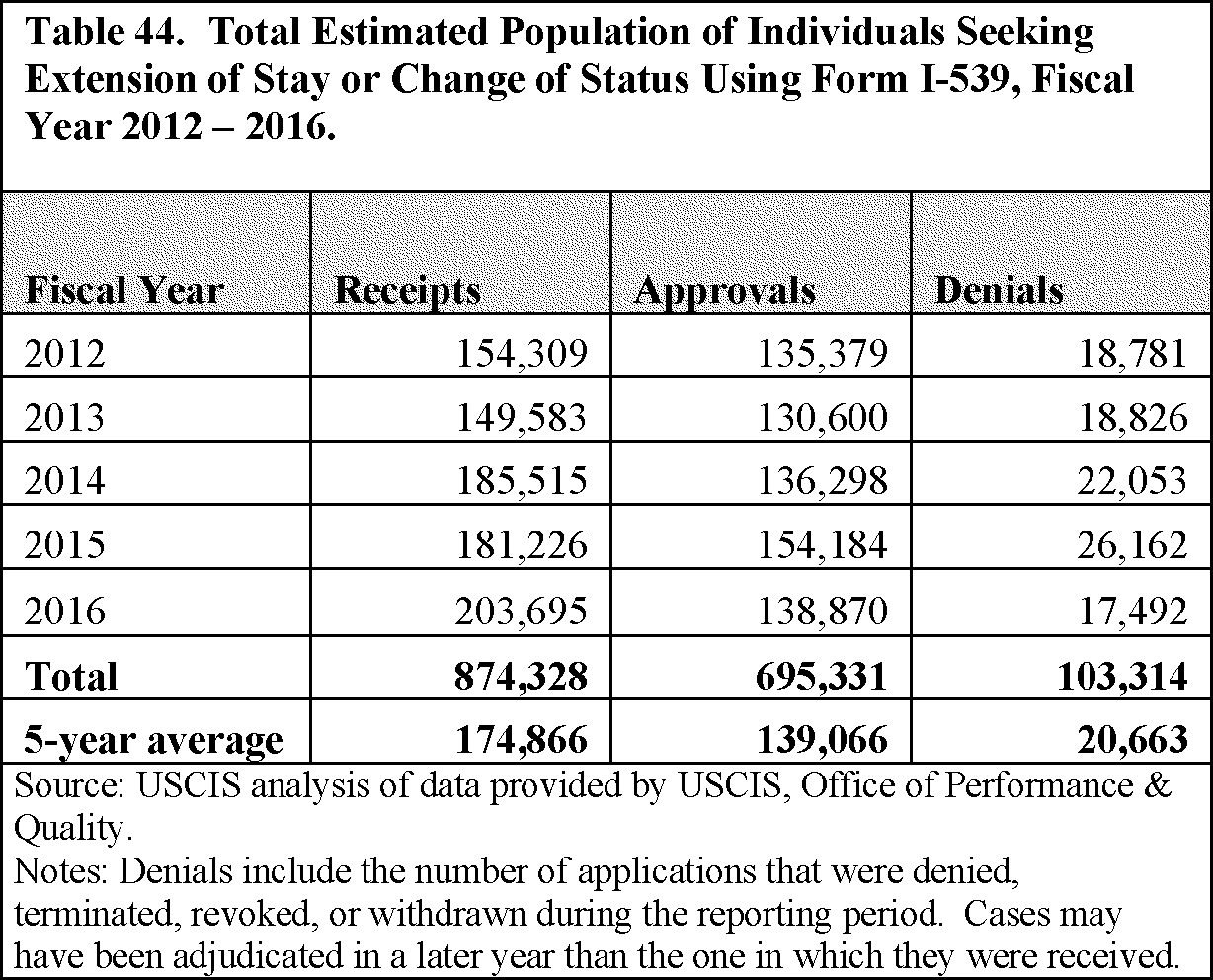

(b) Population Seeking Extension of Stay of Change of Status

4. Cost-Benefit Analysis

(a) Baseline Estimates of Current Costs

i. Determination of Inadmissibility Based on Public Charge Grounds

a. Form I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status

b. Form I-693, Report of Medical Examination and Vaccination Record

c. Form I-912, Request for Fee Waiver

d. Affidavit of Support Forms

ii. Consideration of Receipt, or Likelihood of Receipt of Public Benefits Defined in Proposed 212.21(b) for Applicants Requesting Extension of Stay or Change of Status

a. Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker

b. Form I-129CW, Petition for a CNMI-Only Nonimmigrant Transitional Worker

c. Form I-539, Application To Extend/Change Nonimmigrant Status

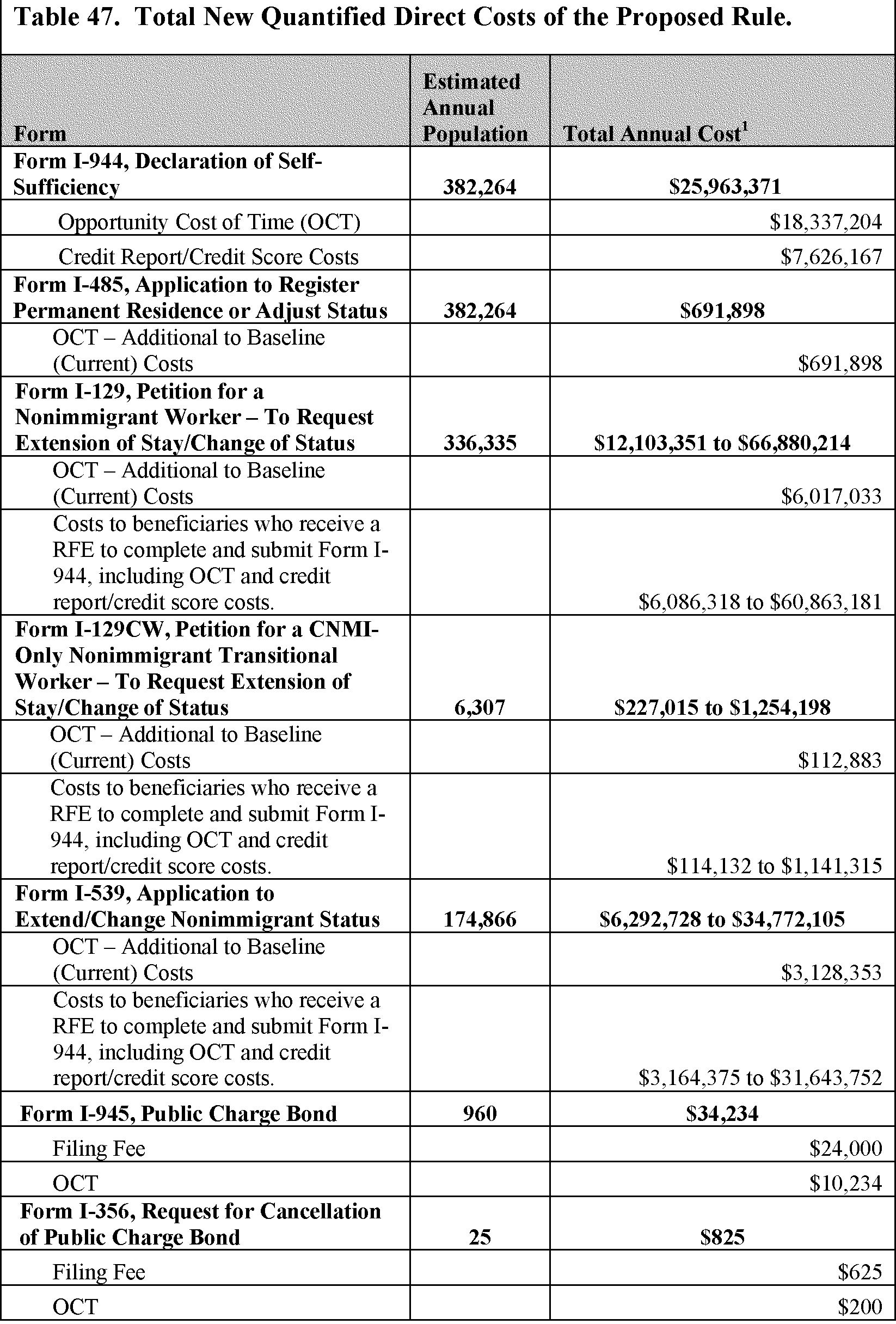

(b) Costs of Proposed Regulatory Changes

i. Form I-944, Declaration of Self-Sufficiency

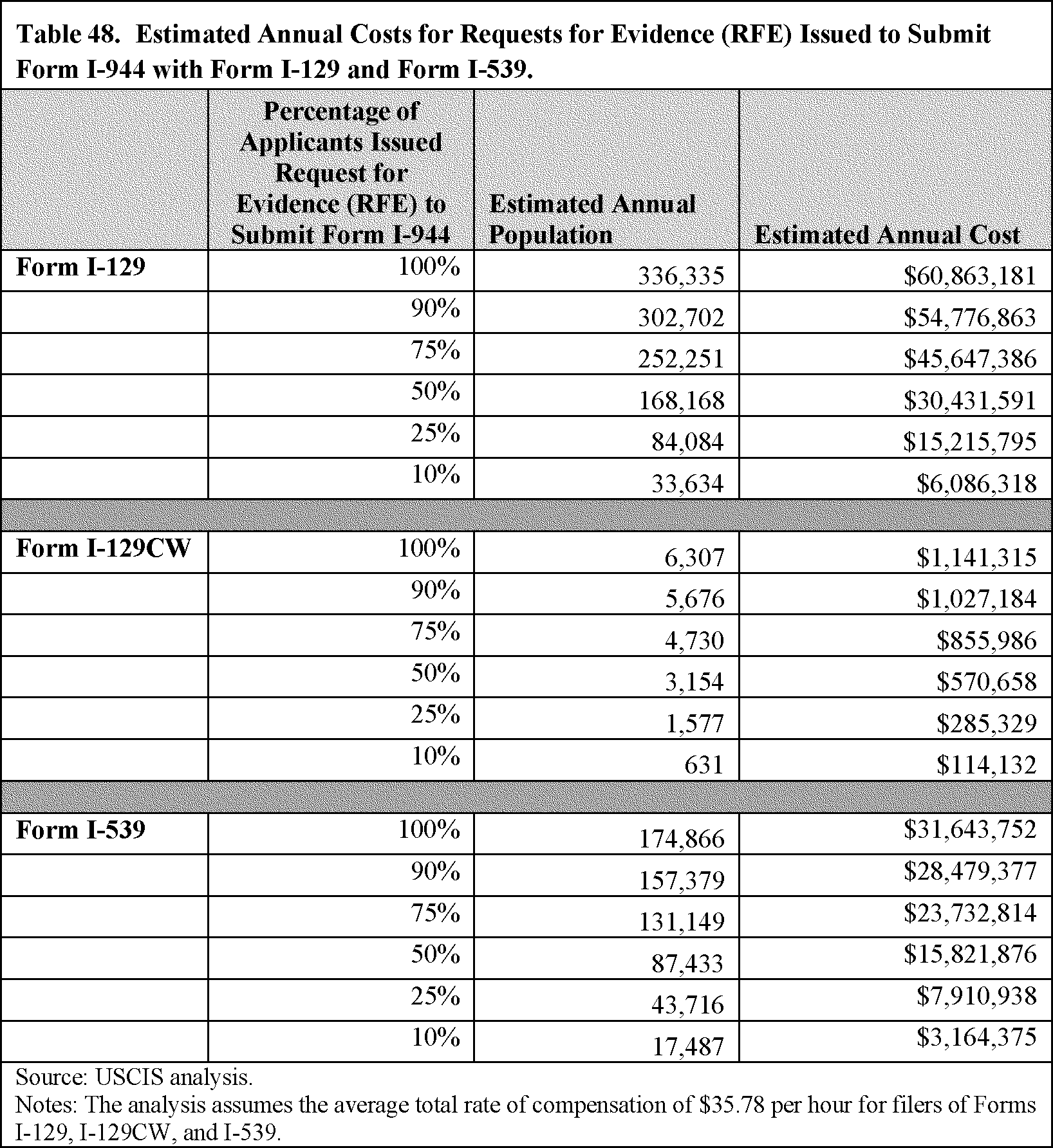

ii. Extension of Stay/Change of Status Using Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker; Form I-129CW, Petition for a CNMI-Only Nonimmigrant Transitional Worker; or Form I-539, Application To Extend/Change Nonimmigrant Status

iii. Public Charge Bond

(c) Transfer of Payments and Indirect Impacts of Proposed Regulatory Changes

(d) Discounted Direct Costs and Reduced Transfer Payments

i. Discounted Direct Costs

ii. Discounted Reduction in Transfer Payments

(e) Costs to the Federal Government

(f) Benefits of Proposed Regulatory Changes

B. Regulatory Flexibility Act

C. Congressional Review Act

D. Unfunded Mandates Reform Act

E. Executive Order 13132 (Federalism)

F. Executive Order 12988 (Civil Justice Reform)

G. Executive Order 13175 Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments

H. Family Assessment

I. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

J. Paperwork Reduction Act

VII. List of Subjects and Regulatory Amendments

Table of Abbreviations

AFM—Adjudicator's Field Manual

ASEC—Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey

BIA—Board of Immigration Appeals

BLS—U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

CDC—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CBP—U.S. Customs and Border Protection

CFR—Code of Federal Regulations

CHIP—Children's Health Insurance Program

CNMI—Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands

DHS—U.S. Department of Homeland Security

DOS—U.S. Department of State

FAM—Foreign Affairs Manual

FCRA—Fair Credit Reporting Act

FPG—Federal Poverty Guidelines

FPL—Federal Poverty Level

Form DS-2054—Medical Examination For Immigrant or Refugee Applicant

Form I-129—Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker

Form I-129CW—Petition for a CNMI-Only Nonimmigrant Transitional Worker

Form I-130—Petition for Alien Relative

Form I-140—Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker

Form I-290B—Notice of Appeal or Motion

Form I-356—Request for Cancellation of Public Charge Bond

Form I-407—Record of Abandonment of Lawful Permanent Resident Status

Form I-485—Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status

Form I-539—Application to Extend/Change Nonimmigrant Status

Form I-600—Petition to Classify Orphan as an Immediate Relative

Form I-693—Report of Medical Examination and Vaccination Record

Form I-800—Petition to Classify Convention Adoptee as an Immediate Relative

Form I-864—Affidavit of Support Under Section 213A of the INA

Form I-864A—Contract Between Sponsor and Household Member

Form I-864EZ—Affidavit of Support Under Section 213A of the Act

Form I-864P—HHS Poverty Guidelines for Affidavit of Support

Form I-864W—Request for Exemption for Intending Immigrant's Affidavit of Support

Form I-912—Request for Fee Waiver

Form I-94—Arrival/Departure Record

Form I-944—Declaration of Self-Sufficiency

Form I-945—Public Charge Bond

Form N-600—Application for Certificate of Citizenship

Form N-600K—Application for Citizenship and Issuance of Certificate Under Section 322

GA- General Assistance

GAO—U.S. Government Accountability Office

HHS—U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

ICE—U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement IIRIRA—Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996

INA—Immigration and Nationality Act

INS—Immigration and Naturalization ServiceStart Printed Page 51116

IRCA—Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986

NHE—National Health Expenditure

PRA—Paperwork Reduction Act

PRWORA—Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996

RFE—Request for Evidence

SAVE—Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements

Secretary—Secretary of Homeland Security

SIPP—Survey of Income and Program Participation

SNAP—Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

SSA—Social Security Administration

SSI—Supplemental Security Income

TANF—Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

USDA—U.S. Department of Agriculture

U.S.C.—United States Code

USCIS—U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

WIC—Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

I. Public Participation

All interested parties are invited to participate in this rulemaking by submitting written data, views, comments and arguments on all aspects of this proposed rule. DHS also invites comments that relate to the economic, legal, environmental, or federalism effects that might result from this proposed rule. Comments must be submitted in English, or an English translation must be provided. Comments that will provide the most assistance to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in implementing these changes will reference a specific portion of the proposed rule, explain the reason for any recommended change, and include data, information, or authority that supports such recommended change.

Instructions: If you submit a comment, you must include the agency name and the DHS Docket No. USCIS-2010-0012 for this rulemaking. Regardless of the method used for submitting comments or material, all submissions will be posted, without change, to the Federal eRulemaking Portal at http://www.regulations.gov, and will include any personal information you provide. Therefore, submitting this information makes it public. You may wish to consider limiting the amount of personal information that you provide in any voluntary public comment submission you make to DHS. DHS may withhold information provided in comments from public viewing that it determines may impact the privacy of an individual or is offensive. For additional information, please read the Privacy Act notice that is available via the link in the footer of http://www.regulations.gov.

Docket: For access to the docket and to read background documents or comments received, go to http://www.regulations.gov, referencing DHS Docket No. USCIS-2010-0012. You may also sign up for email alerts on the online docket to be notified when comments are posted or a final rule is published.

The docket for this rulemaking does not include any comments submitted on the related notice of proposed rulemaking published by INS in 1999.[]

Commenters to the 1999 notice of proposed rulemaking that wish to have their views considered should submit new comments in response to this notice of proposed rulemaking.

II. Executive Summary

DHS seeks to better ensure that aliens subject to the public charge inadmissibility ground are self-sufficient, i.e., do not depend on public resources to meet their needs, but rather rely on their own capabilities, as well as the resources of family members, sponsors, and private organizations.[]

DHS proposes to define the term “public charge” in regulation and to identify the types, amount, and duration of receipt of public benefits that would be considered in public charge inadmissibility determinations. DHS proposes to amend its regulations to interpret the minimum statutory factors for determining whether an alien is inadmissible because he or she is likely to become a public charge. This proposed rule would provide a standard for determining whether an alien who seeks admission into the United States as a nonimmigrant or as an immigrant, or seeks adjustment of status, is likely at any time to become a public charge under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4). DHS also provides a more comprehensive framework under which USCIS will consider public charge inadmissibility. DHS proposes that certain paper-based applications to USCIS would require additional evidence related to public charge considerations. Due to operational limitations, this additional evidence would not generally be required at ports of entry.

DHS also proposes amending the nonimmigrant extension of stay and change of status regulations by exercising its authority to set additional conditions on granting such benefits. Finally, DHS proposes to revise its regulations governing the discretion of the Secretary of Homeland Security (Secretary) to accept a public charge bond under section 213 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1183, for those seeking adjustment of status.

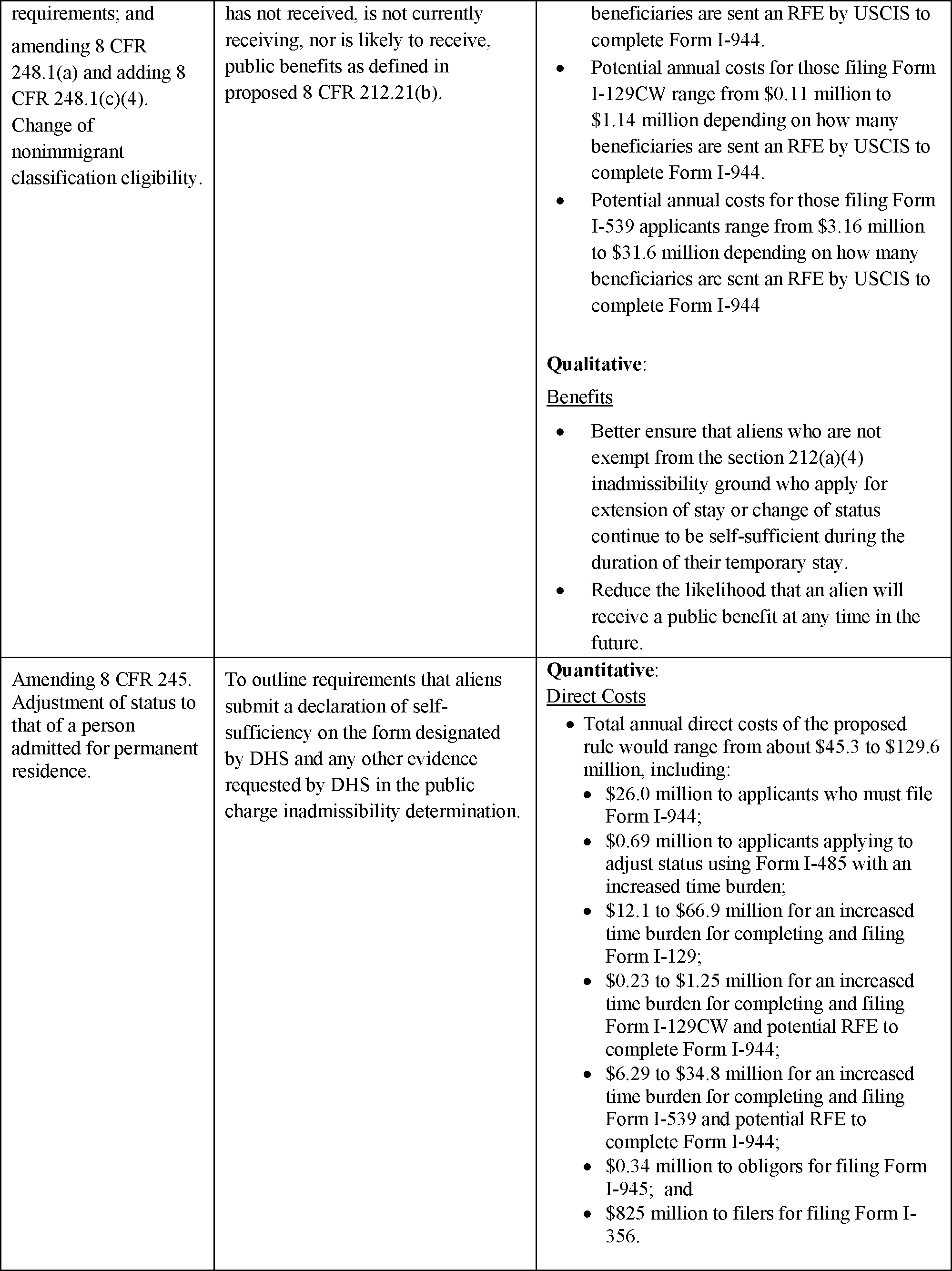

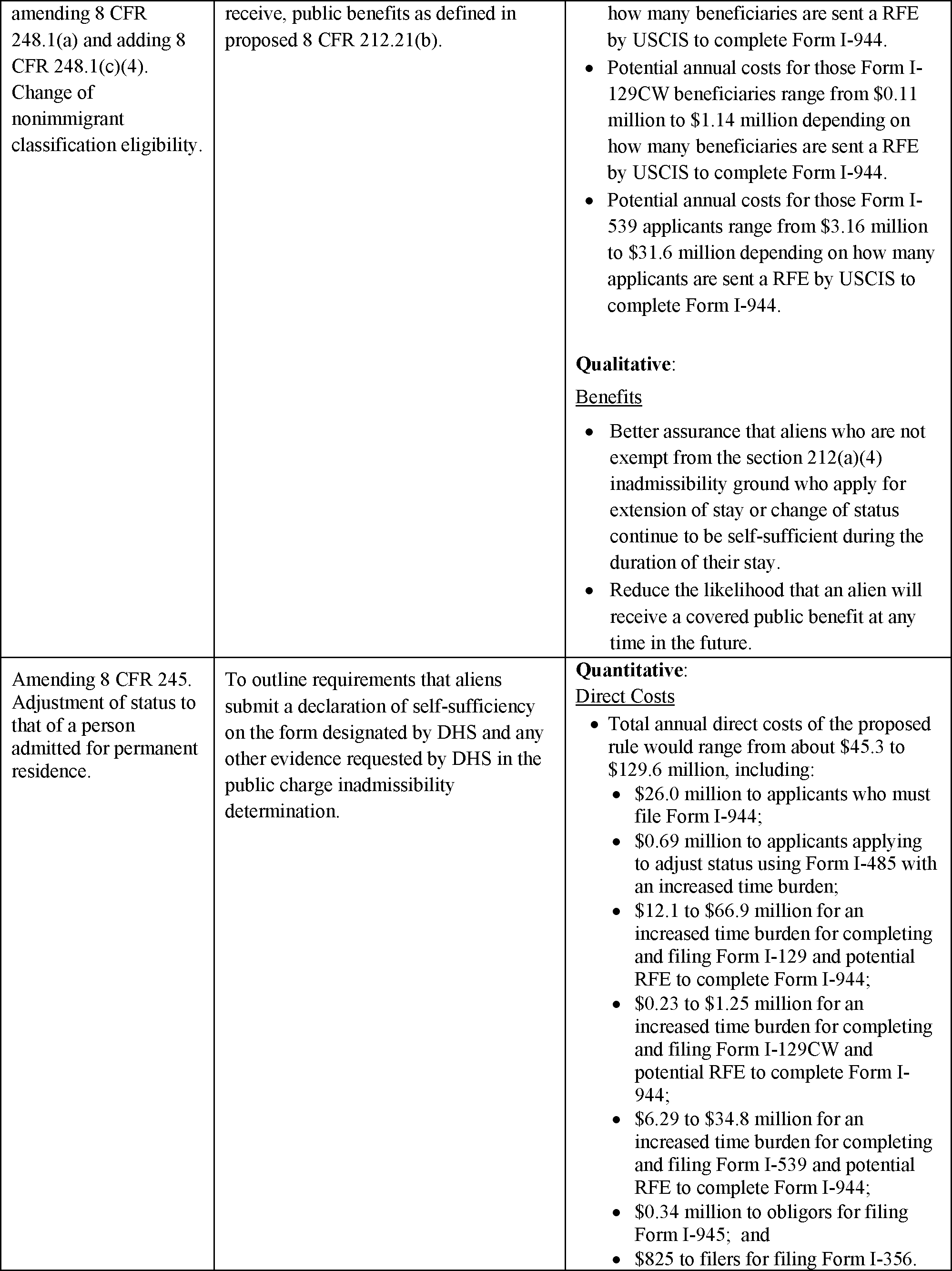

A. Major Provisions of the Regulatory Action

DHS proposes to include the following major changes:

- Amending 8 CFR 103.6, Surety bonds. The amendments to this section set forth DHS's discretion to approve public charge bonds, cancellation, bond schedules, and breach of bond, and move principles governing public charge bonds to 8 CFR 213.1, as proposed to be revised in this NPRM.

- Amending 8 CFR 103.7, adding fees for new Form I-945, Public Charge Bond, and Form I-356, Request for Cancellation of Public Charge Bond.

- Adding 8 CFR 212.20, Applicability of public charge inadmissibility. This section identifies the categories of aliens that are subject to the public charge inadmissibility determination.

- Adding 212.21, Definitions. This section establishes key regulatory definitions, including public charge, public benefit, likely at any time to become a public charge, and household.

- Adding 212.22, Public charge determination. This section clarifies that evaluating the likelihood of becoming a public charge is a prospective determination based on the totality of the circumstances. This section provides details on how the statute's mandatory factors would be considered when making a public charge inadmissibility determination.

- Adding 212.23, Exemptions and waivers for the public charge ground of inadmissibility. This section provides a list of statutory and regulatory exemptions from and waivers of inadmissibility based on public charge.

- Adding 212.24 Valuation of monetizable benefits. This section provides the methodology for calculating the annual aggregate amount of the portion attributable to the alien for the monetizable benefits and considered in the public charge inadmissibility determination.

- Amending 8 CFR 213.1, Adjustment of status of aliens on submission of a public charge bond. The updates to this section change the title of this section and add specifics to the public charge bond provision for aliens who are seeking adjustment of status, including the discretionary availability and the minimum amount for a public charge bond.

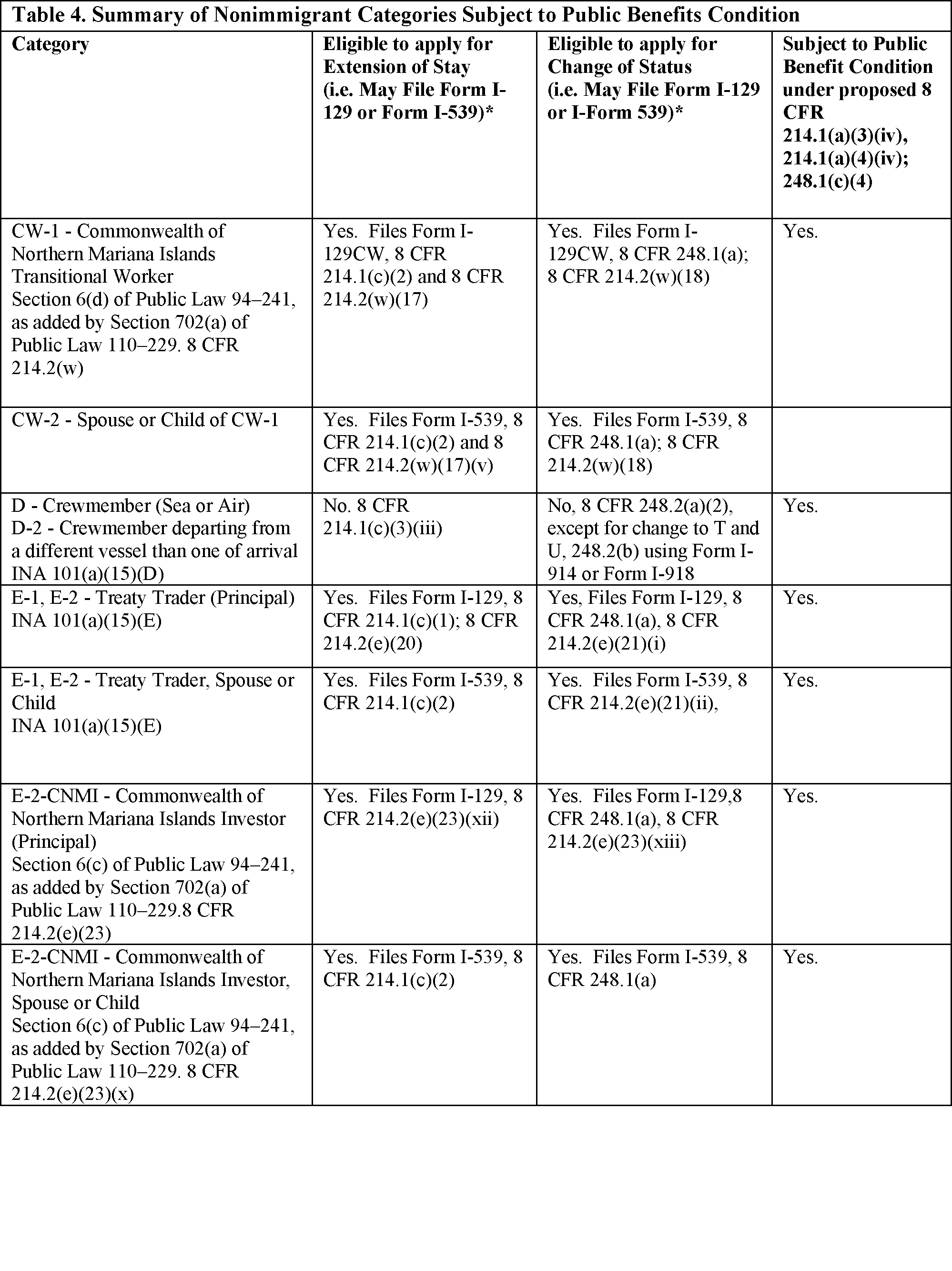

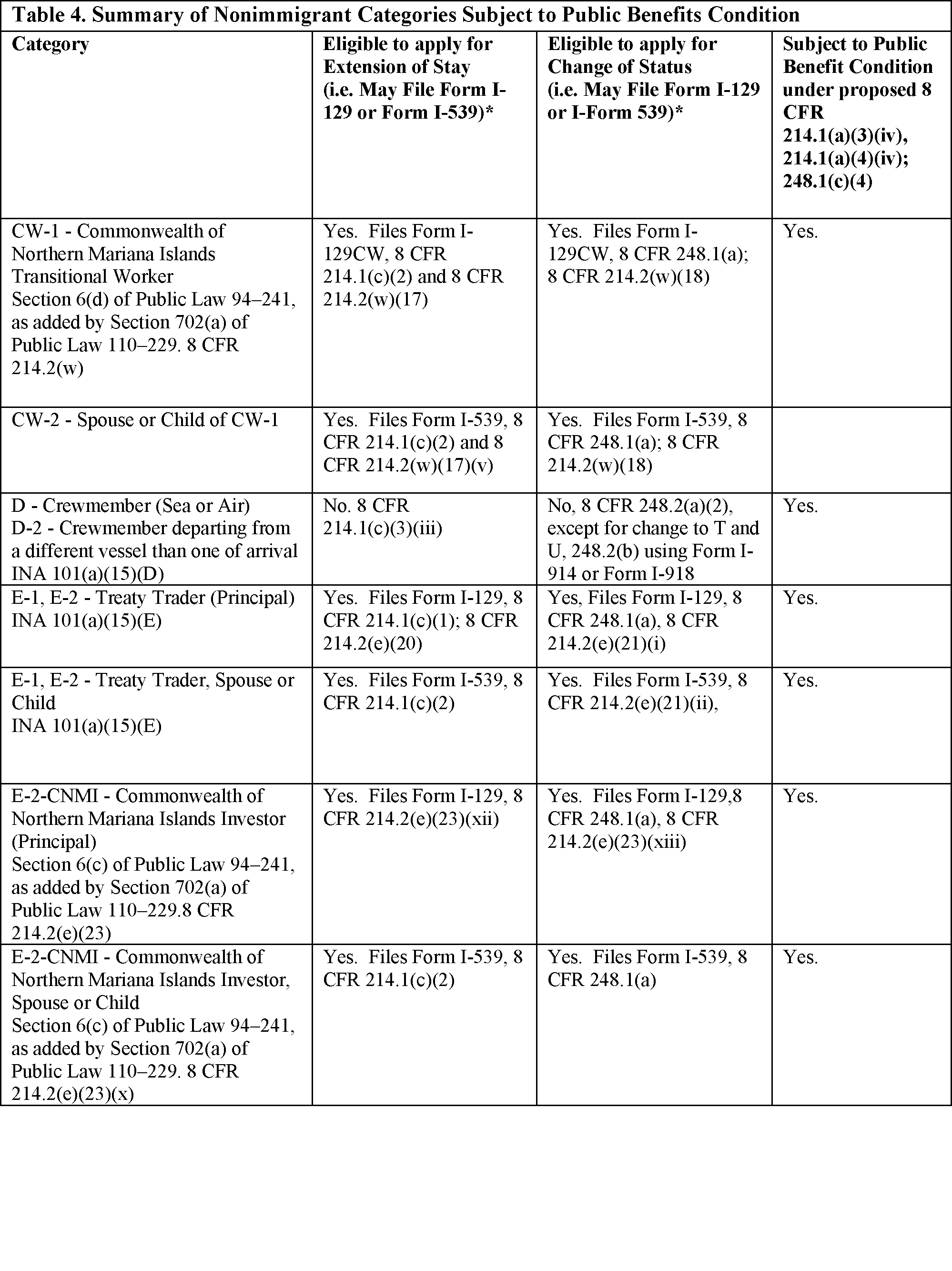

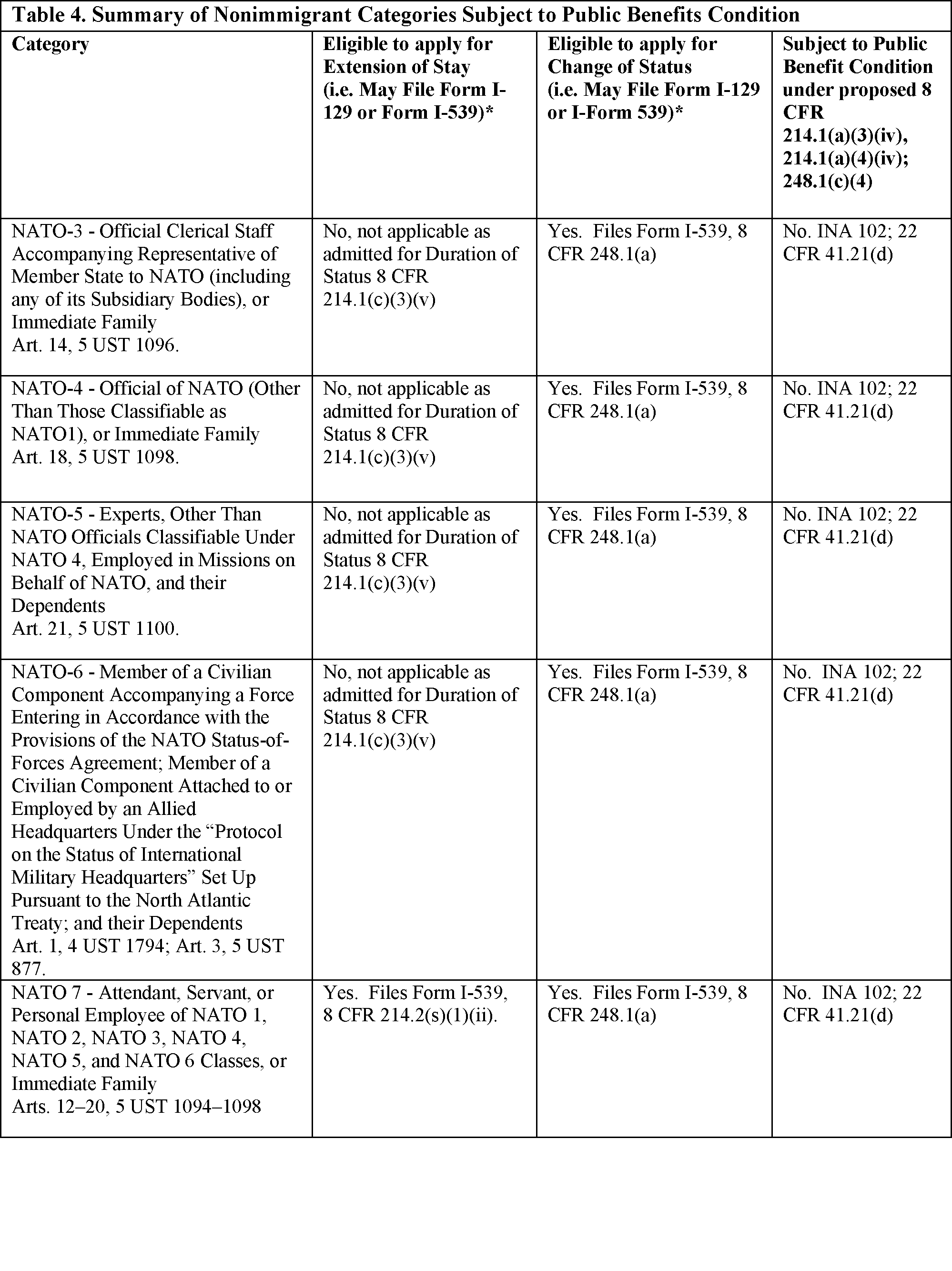

- Amending 8 CFR 214.1, Requirements for admission, extension, and maintenance of status. These amendments provide that, with limited Start Printed Page 51117exceptions, an application for extension of nonimmigrant stay will be denied unless the applicant demonstrates that he or she has not received since obtaining the nonimmigrant status he or she seeks to extend, is not receiving, and is not likely to receive, public benefits as described in 8 CFR 212.21(b). Where section 212(a)(4) of the Act does not apply to the nonimmigrant category that the alien seeks to extend, this provision does not apply.

- Amending 8 CFR 245.4 Documentary requirements. These amendments require applicants for adjustment of status to file the new USCIS Form I-944, Declaration of Self-Sufficiency, to facilitate USCIS' public charge inadmissibility determination.

- Amending 8 CFR 248.1, Change of nonimmigrant classification eligibility. This section provides that with limited exceptions, an application to change nonimmigrant status will be denied unless the applicant demonstrates that he or she has not received since obtaining the nonimmigrant status from which the alien seeks to change, is not currently receiving, nor is likely to receive public benefits in the future, as described in proposed 8 CFR 212.21(b). Where section 212(a)(4) of the Act does not apply to the nonimmigrant category to which the alien requests a change of status this provision does not apply.

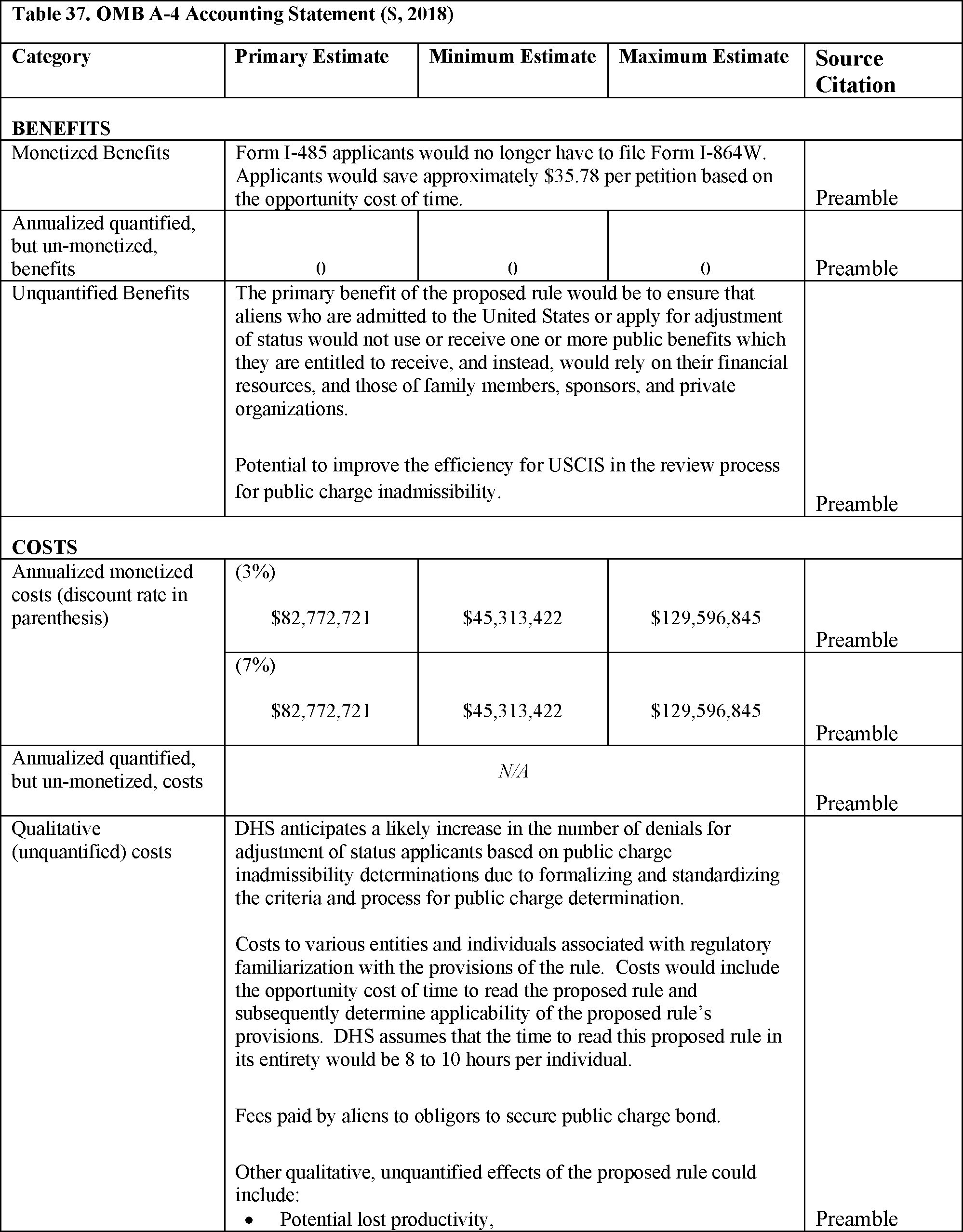

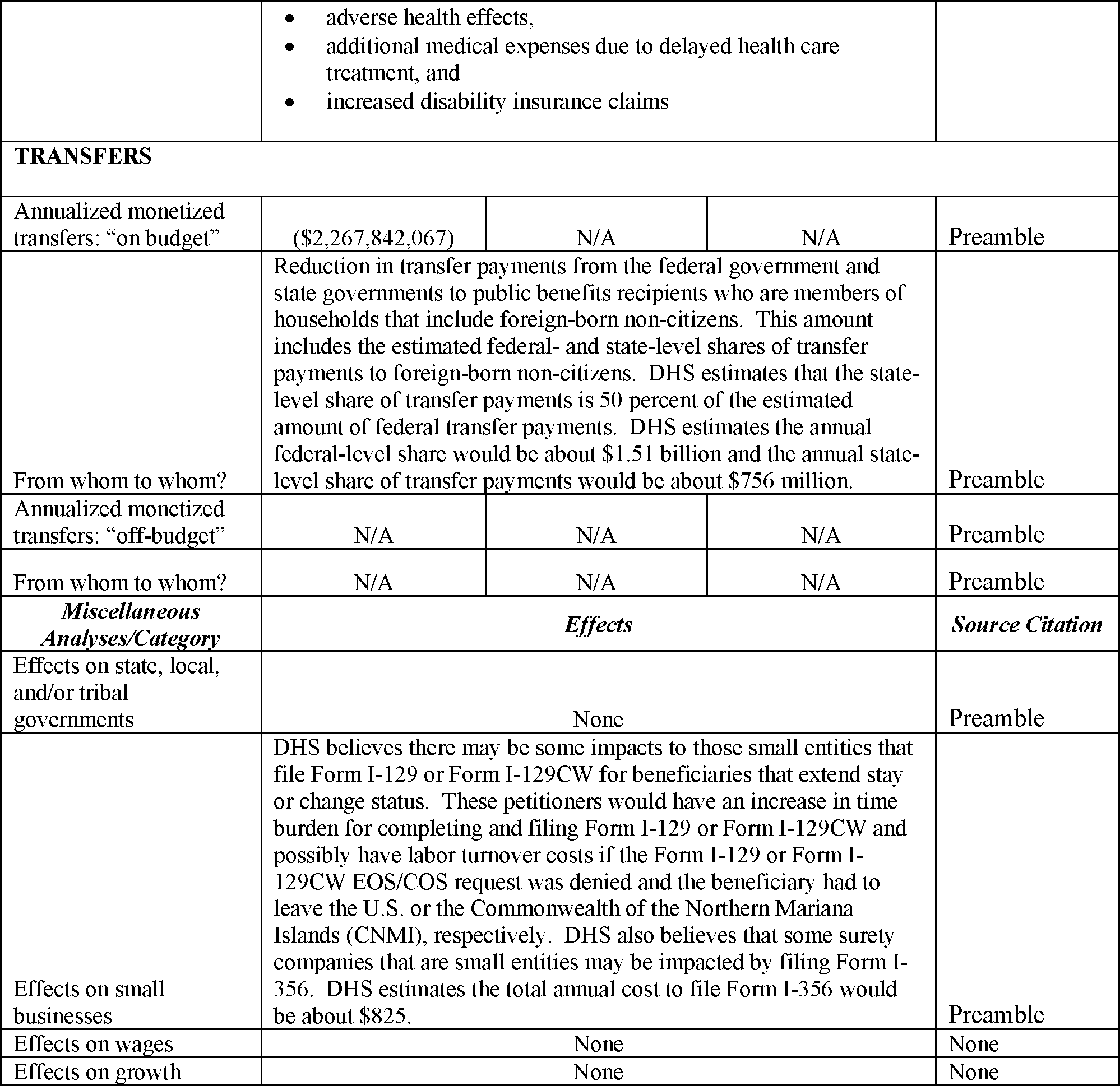

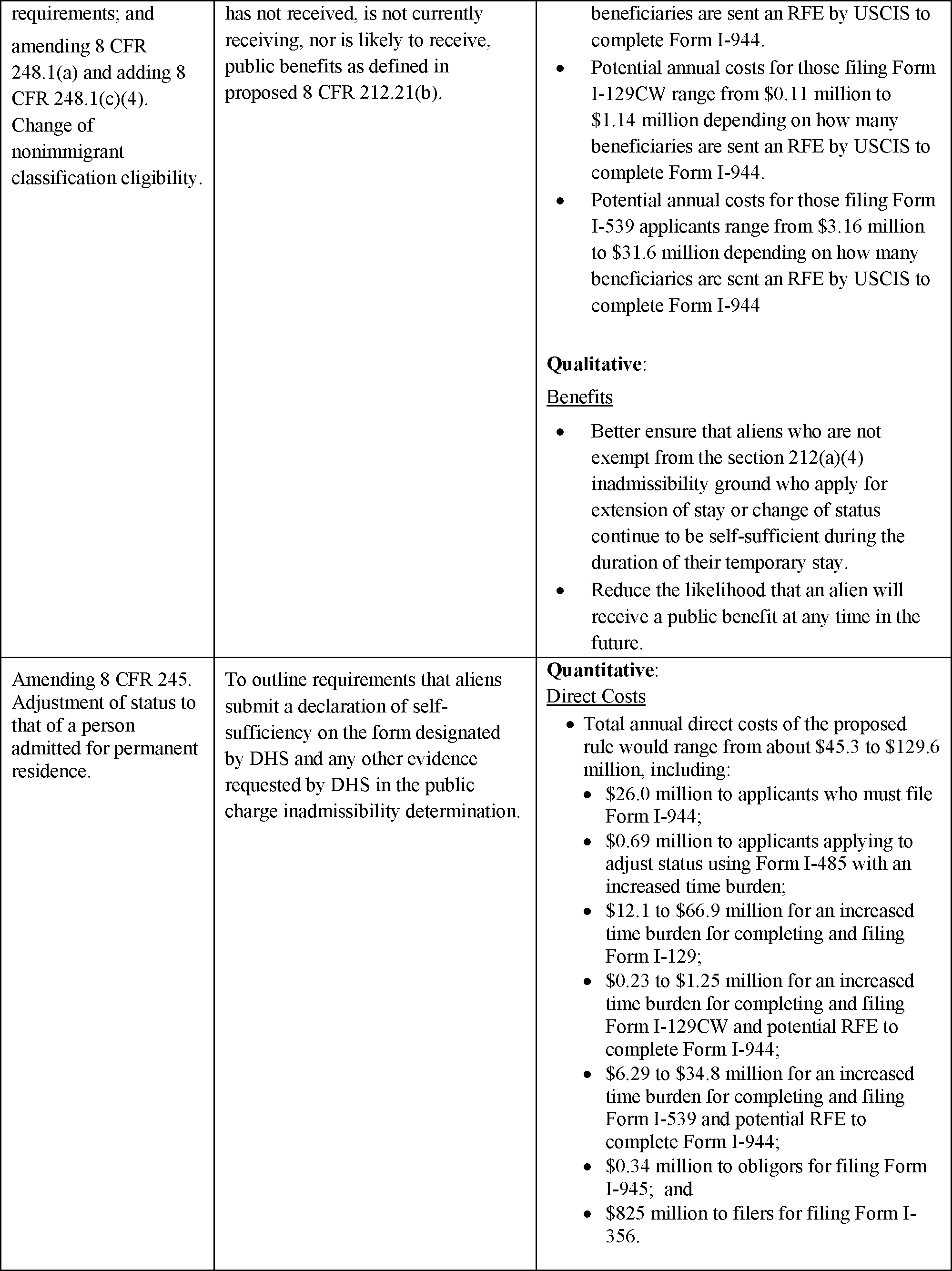

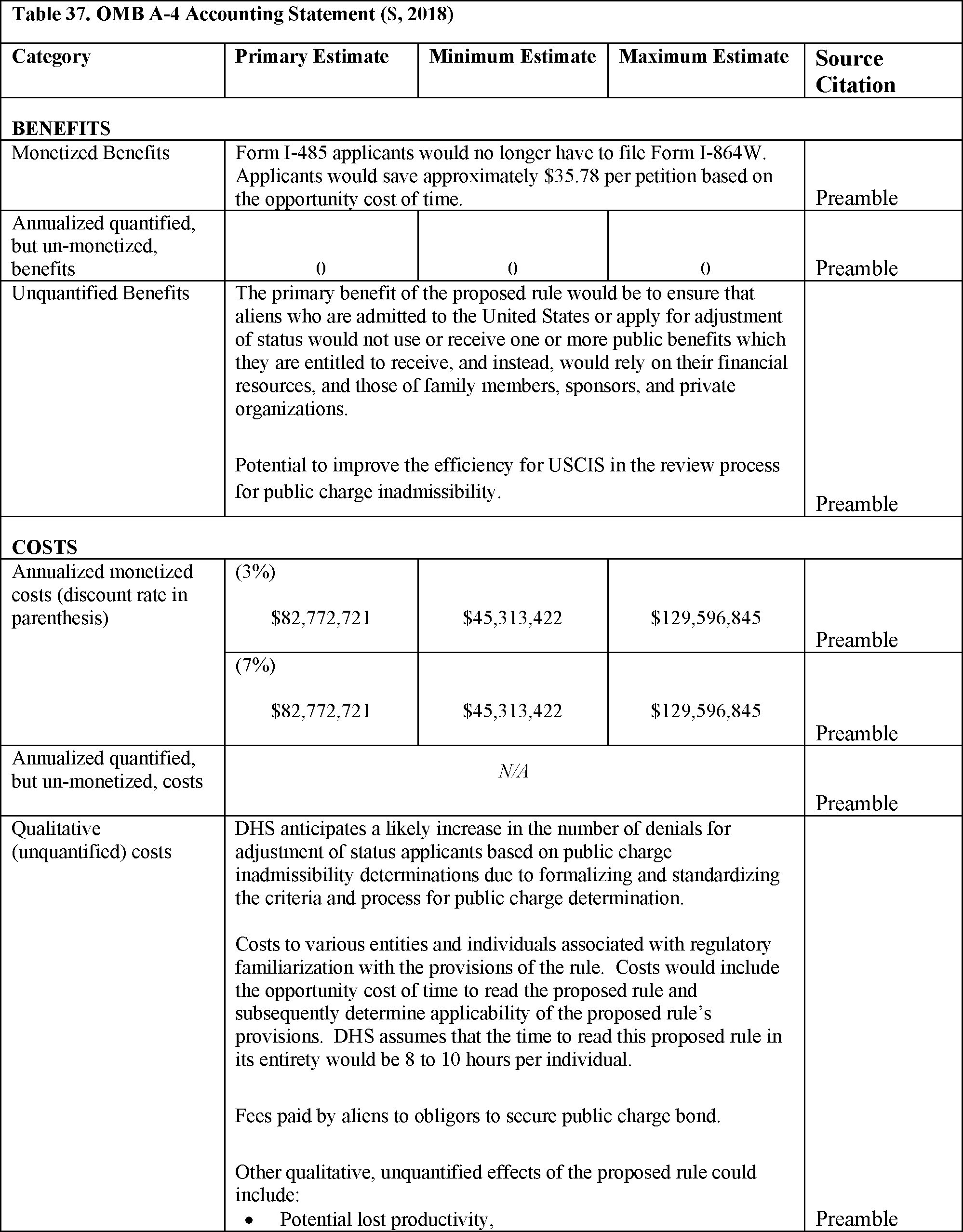

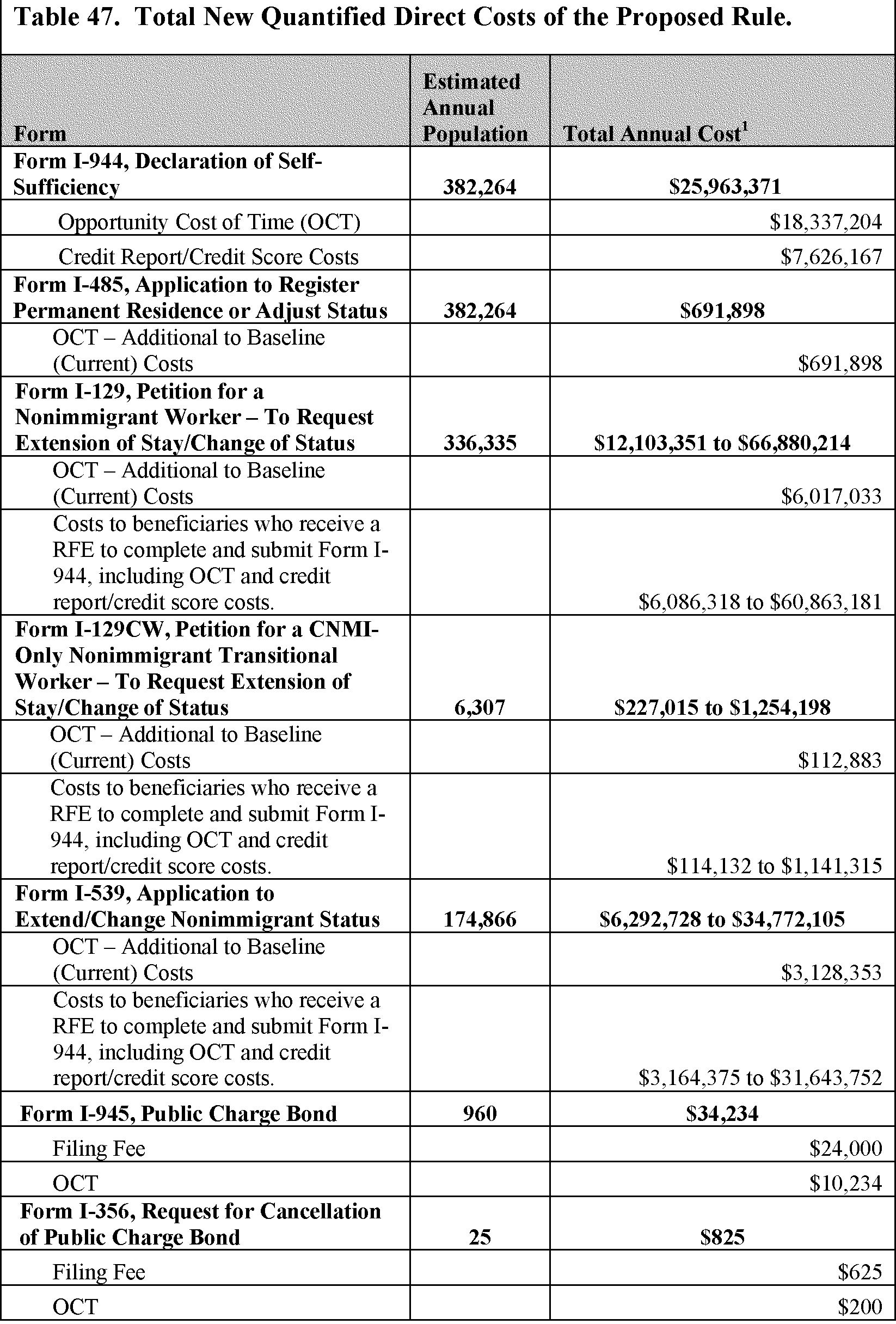

B. Costs and Benefits

This proposed rule would impose new costs on the population applying to adjust status using Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status (Form I-485) that are subject to the public charge grounds on inadmissibility. DHS would now require any adjustment applicants subject to the public charge inadmissibility ground to submit Form I-944 with their Form I-485 to demonstrate they are not likely to become a public charge.

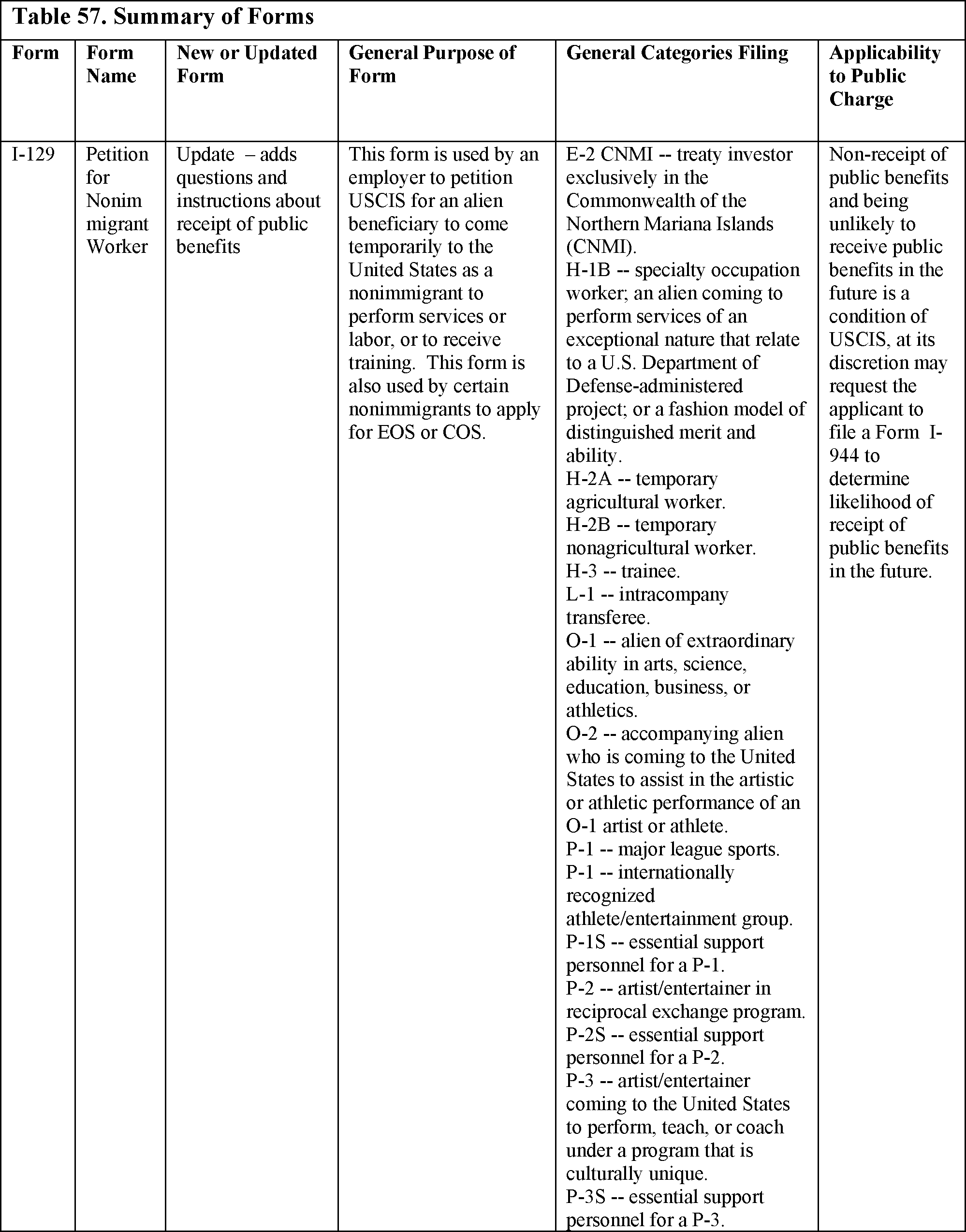

The proposed rule would also impose additional costs for seeking extension of stay or change of status by filing Form I-129 (Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker); Form I-129CW (Petition for a CNMI-Only Nonimmigrant Transitional Worker); or Form I-539 (Application to Extend/Change Nonimmigrant Status) as applicable. The associated time burden estimate for completing these forms would increase because these applicants would be required to demonstrate that they have not received, are not currently receiving, nor are likely in the future to receive, public benefits as described in proposed 8 CFR 212.21(b). These applicants may also incur additional costs if DHS determines that they are required to submit Form I-944 in support of their applications for extension of stay or change of status. Moreover, the proposed rule would impose new costs associated with the proposed public charge bond process, including new costs for completing and filing Form I-945 (Public Charge Bond), and Form I-356 (Request for Cancellation of Public Charge Bond).

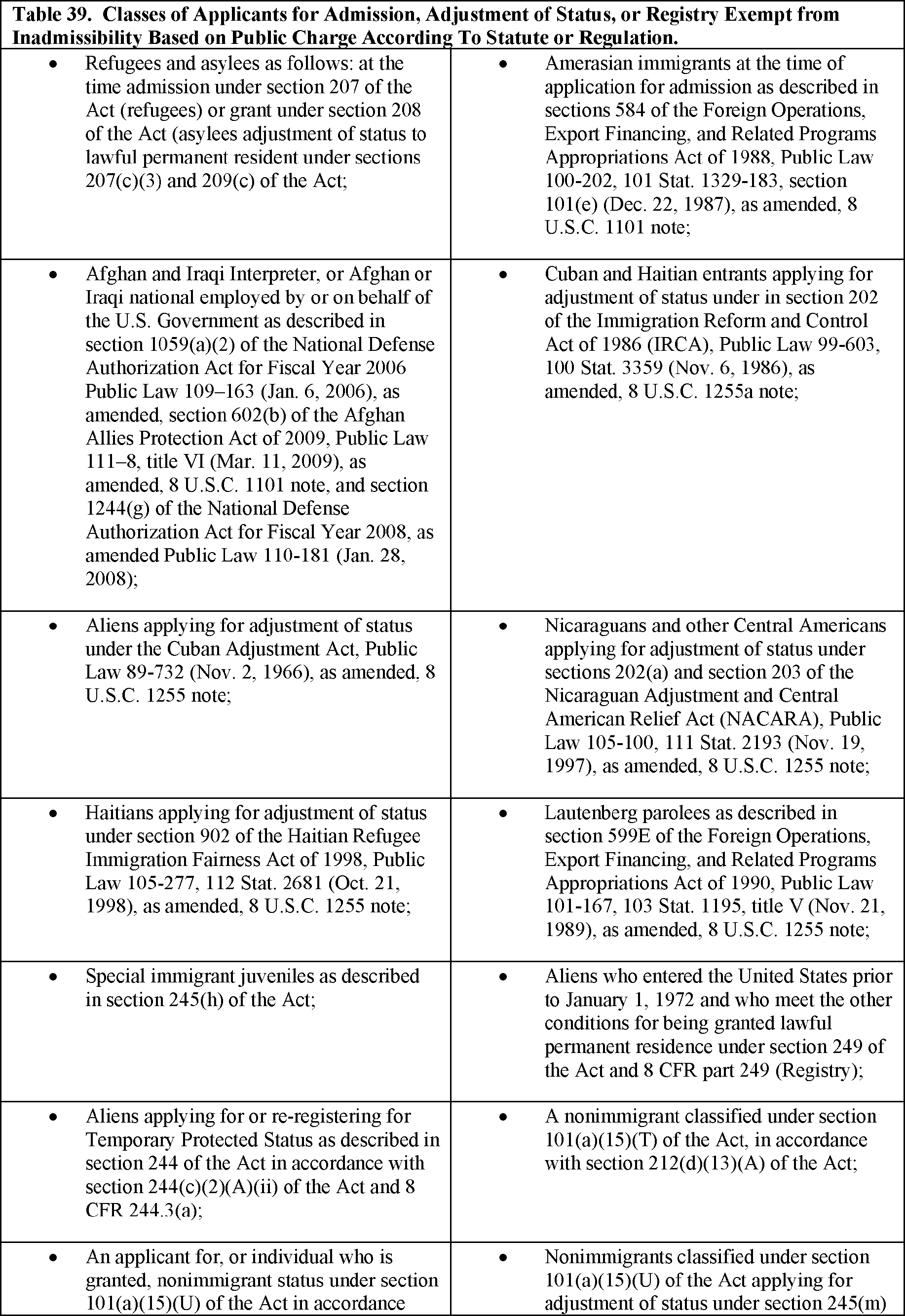

DHS estimates that the additional total cost of the proposed rule would range from approximately $45,313,422 to $129,596,845 annually for the population applying to adjust status who also would be required to file Form I-944, the population applying for extension of stay or change of status that would experience opportunity costs in time associated with the increased time burden estimates for completing Form I-485, Form I-129, FormI-129CW, and FormI-539, and the population requesting or cancelling a public charge bond using Form I-945 and Form I-356, respectively.

Over the first 10 years of implementation, DHS estimates the total quantified new direct costs of the proposed rule would range from about $453,134,220 to $1,295,968,450 (undiscounted). DHS estimates that the 10-year discounted total direct costs of this proposed rule would range from about $386,532,679 to $1,105,487,375 at a 3 percent discount rate and about $318,262,513 to $910,234,008 at a 7 percent discount rate.

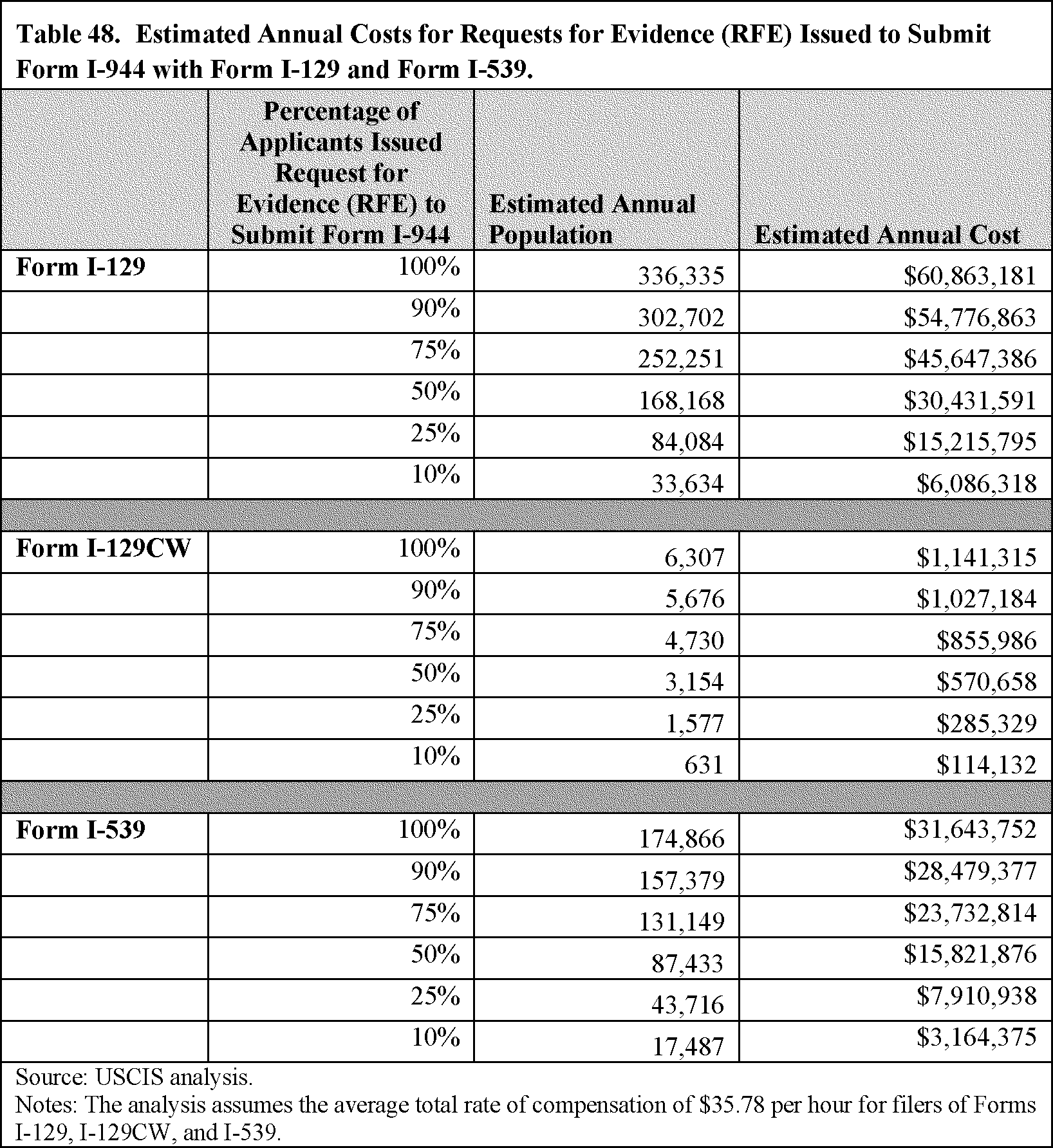

The proposed rule would impose new costs on the population seeking extension of stay or change of status using Form I-129, Form I-129CW, or Form I-539. For any of these forms, USCIS officers would then be able to exercise discretion in determining whether it would be necessary to issue a request for evidence (RFE) requesting the applicant to submit Form I-944. DHS conducted a sensitivity analysis estimating the potential cost of filing Form I-129, Form I-129CW, or Form I-539 for a range of 10 to 100 percent of filers receiving an RFE requesting they submit Form I-944. The costs to Form I-129 beneficiaries who may receive an RFE to file Form I-944 range from $6,086,318 to $60,863,181 annually and the costs to Form I-129CW beneficiaries who may receive such an RFE from $114,132 to $1,141,315 annually. The costs to Form I-539 applicants who may receive an RFE to file Form I-944 range from $3,164,375 to $31,643,752 annually.

Simultaneously, DHS is proposing to eliminate the use and consideration of the Request for Exemption for Intending Immigrant's Affidavit of Support (Form I-864W), currently applicable to certain classes of aliens. In lieu of Form I-864W, the alien would indicate eligibility for the exemption of the affidavit of support requirement on Form I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status.

The proposed rule would potentially impose new costs on individuals or companies (obligors) if an alien has been found to be inadmissible on public charge grounds, but has been given the opportunity to submit a public charge bond, for which USCIS intends to use the new Form I-945. DHS estimates the total cost to file Form I-945 would be at minimum about $34,234 annually.[]

The proposed rule would also impose new costs on aliens or obligors who would submit a Form I-356; DHS estimates the total cost to file Form I-356 would be approximately $825 annually.[]

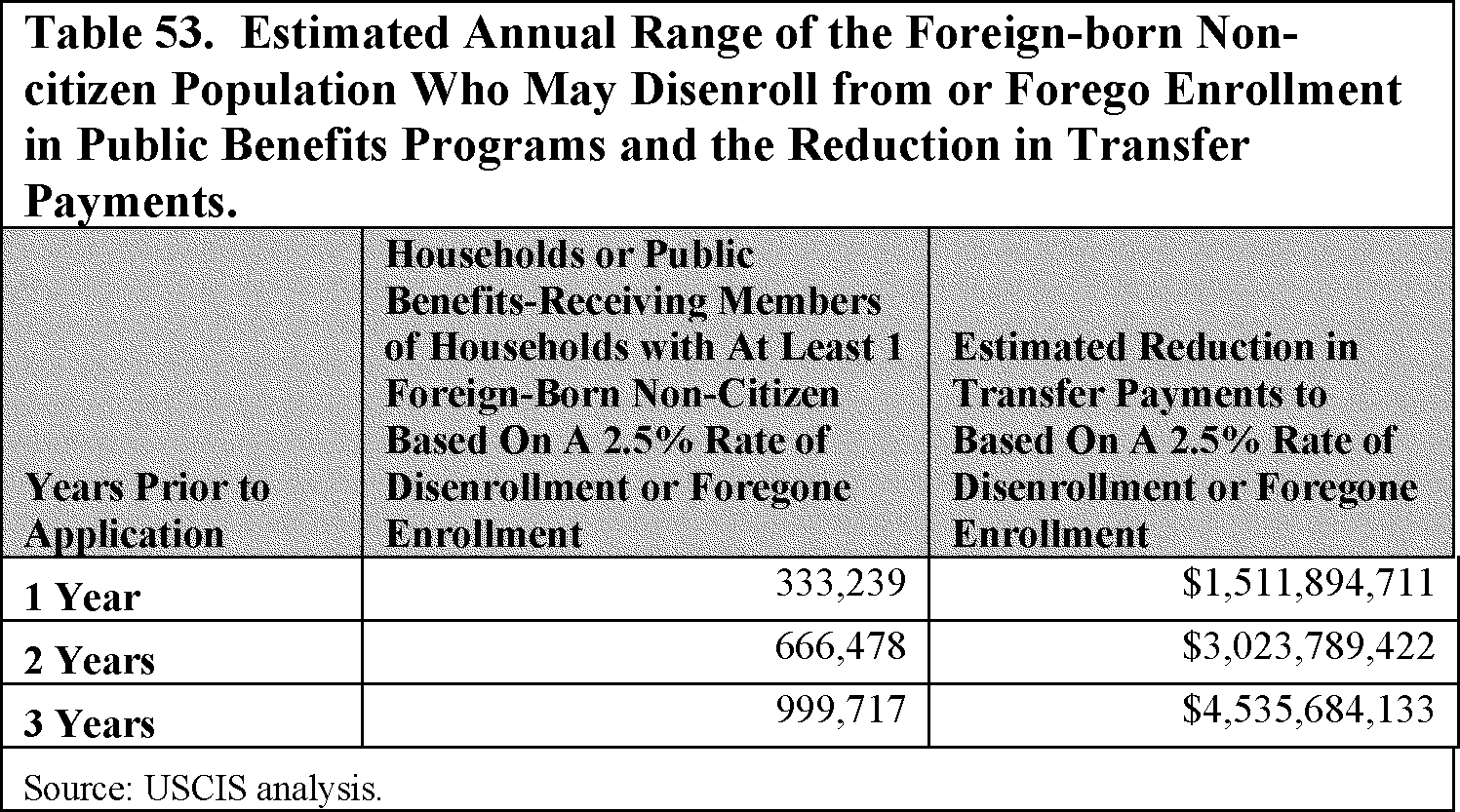

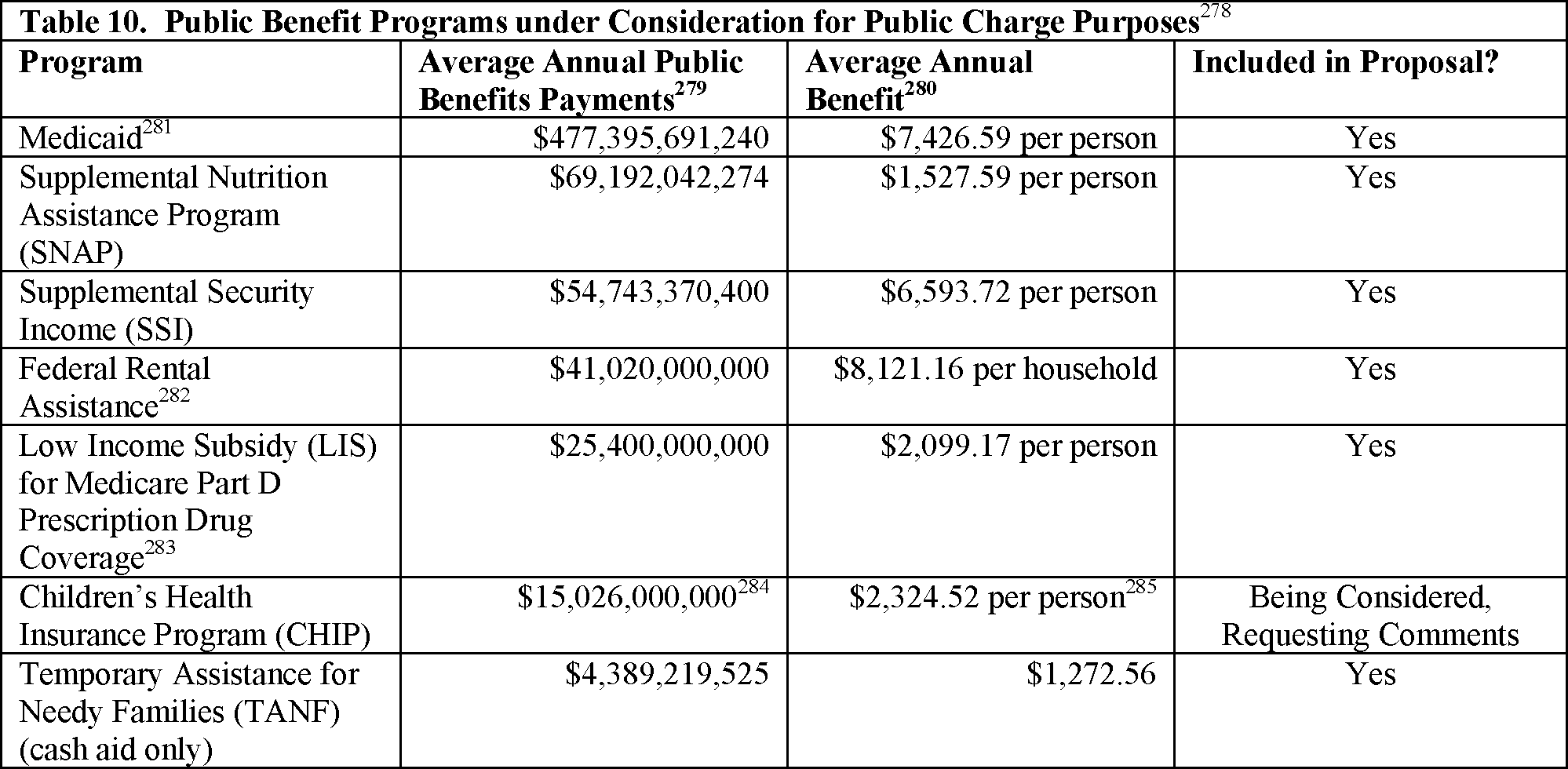

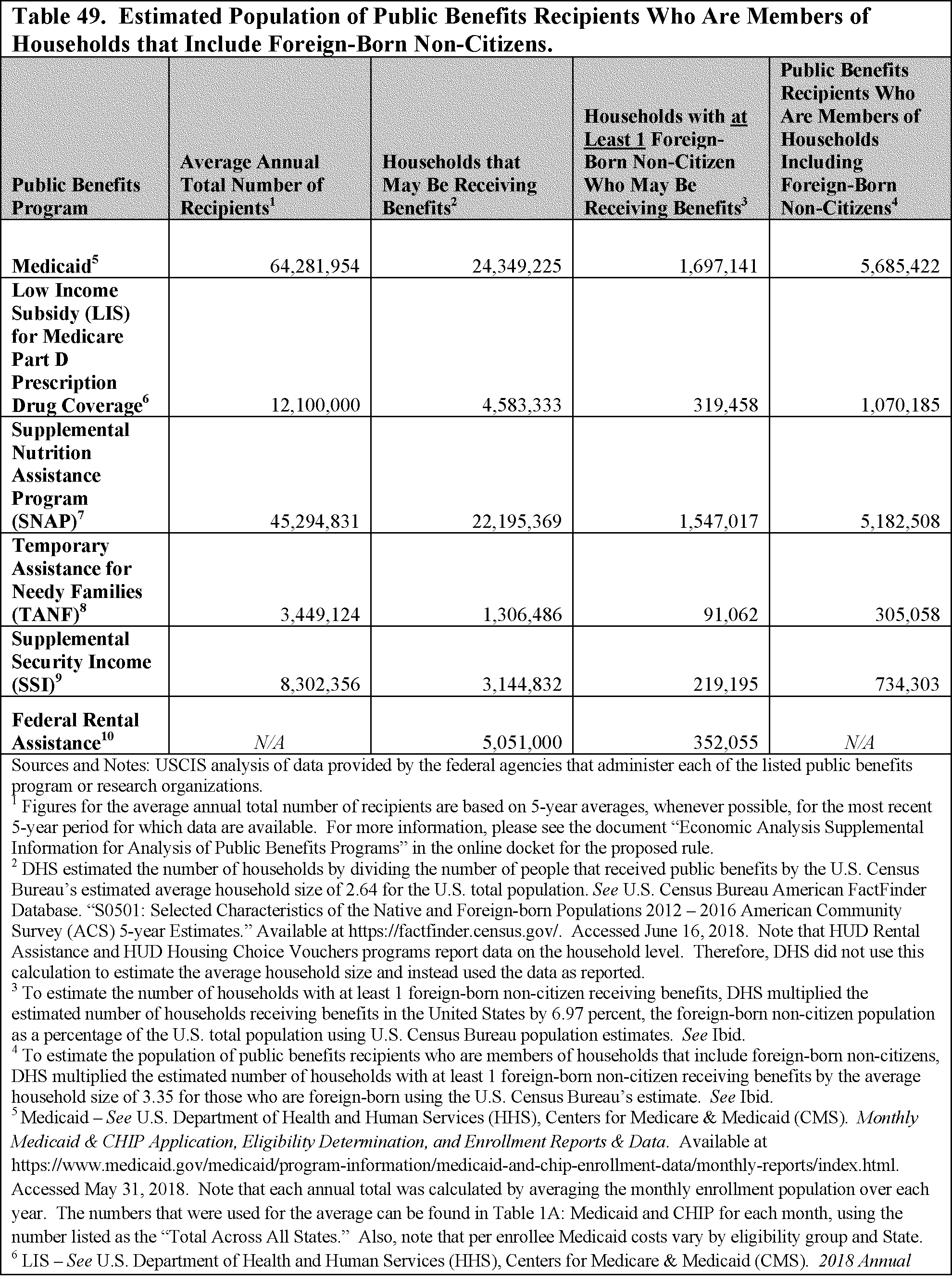

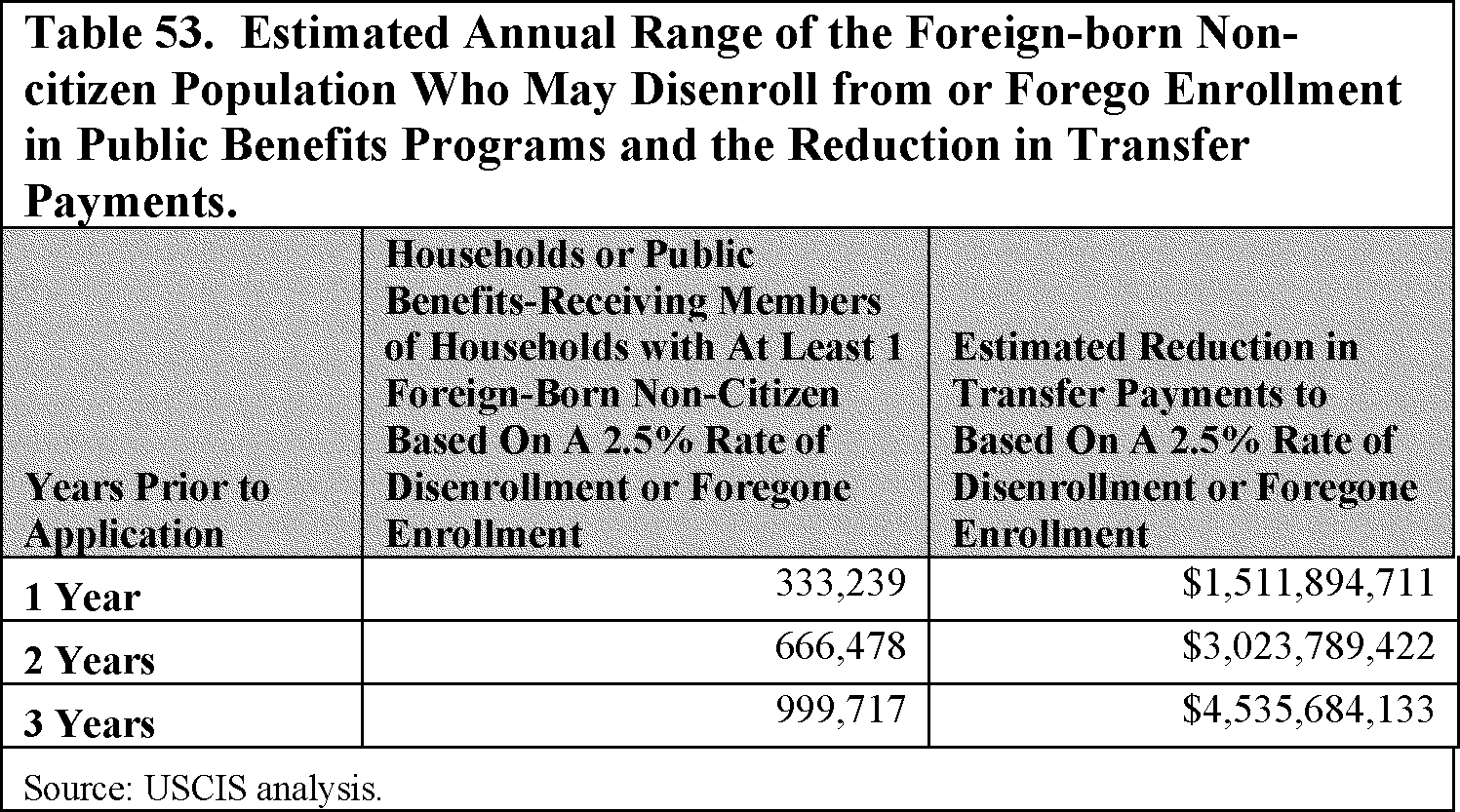

Moreover, the proposed rule would also result in a reduction in transfer payments from the federal government to individuals who may choose to disenroll from or forego enrollment in a public benefits program. Individuals may make such a choice due to concern about the consequences to that person receiving public benefits and being found to be likely to become a public charge for purposes outlined under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, even if such individuals are otherwise eligible to receive benefits. For the proposed rule, DHS estimates that the total reduction in transfer payments from the federal and state governments would be approximately $2.27 billion annually due to disenrollment or foregone enrollment in public benefits programs by aliens who may be receiving public benefits. DHS estimates that the 10-year discounted transfer payments of this proposed rule would be approximately $19.3 billion at a 3 percent discount rate and about $15.9 billion at a 7 percent discount rate. Because state

Start Printed Page 51118

participation in these programs may vary depending on the type of benefit provided, DHS was only able to estimate the impact of state transfers. For example, the federal government funds all SNAP food expenses, but only 50 percent of allowable administrative costs for regular operating expenses.[] Similarly, Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP) in some HHS programs like Medicaid can vary from between 50 percent to an enhanced rate of 100 percent in some cases.[]

However, assuming that the state share of federal financial participation (FFP) is 50 percent, the 10-year discounted amount of state transfer payments of this proposed policy would be approximately $9.65 billion at a 3 percent discount rate and about $7.95 billion at a 7 percent discount rate. DHS recognizes that reductions in federal and state transfers under federal benefit programs may have downstream and upstream impacts on state and local economies, large and small businesses, and individuals. For example, the rule might result in reduced revenues for healthcare providers participating in Medicaid, pharmacies that provide prescriptions to participants in the Medicare Part D Low Income Subsidy (LIS) program, companies that manufacture medical supplies or pharmaceuticals, grocery retailers participating in SNAP, agricultural producers who grow foods that are eligible for purchase using SNAP benefits, or landlords participating in federally funded housing programs.

Additionally, the proposed rule would add new direct and indirect costs on various entities and individuals associated with regulatory familiarization with the provisions of this rule. Familiarization costs involve the time spent reading the details of a rule to understand its changes. To the extent that an individual or entity directly regulated by the rule incurs familiarization costs, those familiarization costs are a direct cost of the rule. For example, immigration lawyers, immigration advocacy groups, health care providers of all types, non-profit organizations, non-governmental organizations, and religious organizations, among others, may need or want to become familiar with the provisions of this proposed rule. An entity, such as a non-profit or advocacy group, may have more than one person that reads the rule. Familiarization costs incurred by those not directly regulated are indirect costs. DHS estimates the time that would be necessary to read this proposed rule would be approximately 8 to 10 hours per person, resulting in opportunity costs of time.

The primary benefit of the proposed rule would be to help ensure that aliens who apply for admission to the United States, seek extension of stay or change of status, or apply for adjustment of status are self-sufficient, i.e., do not depend on public resources to meet their needs, but rather rely on their own capabilities and the resources of their family, sponsor, and private organizations.[]

DHS also anticipates that the proposed rule would produce some benefits from the elimination of Form I-864W. The elimination of this form would potentially reduce the number of forms USCIS would have to process, although it likely would not reduce overall processing burden. DHS estimates the amount of cost savings that would accrue from eliminating Form I-864W would be $35.78 per petitioner.[]

However, DHS is unable to determine the annual number of filings of Form I-864W and, therefore, is currently unable to estimate the total annual cost savings of this change. A public charge bond process would provide benefits to applicants as they potentially would be given the opportunity to adjust their status if otherwise admissible, at the discretion of DHS, after a determination that they are likely to become public charges.

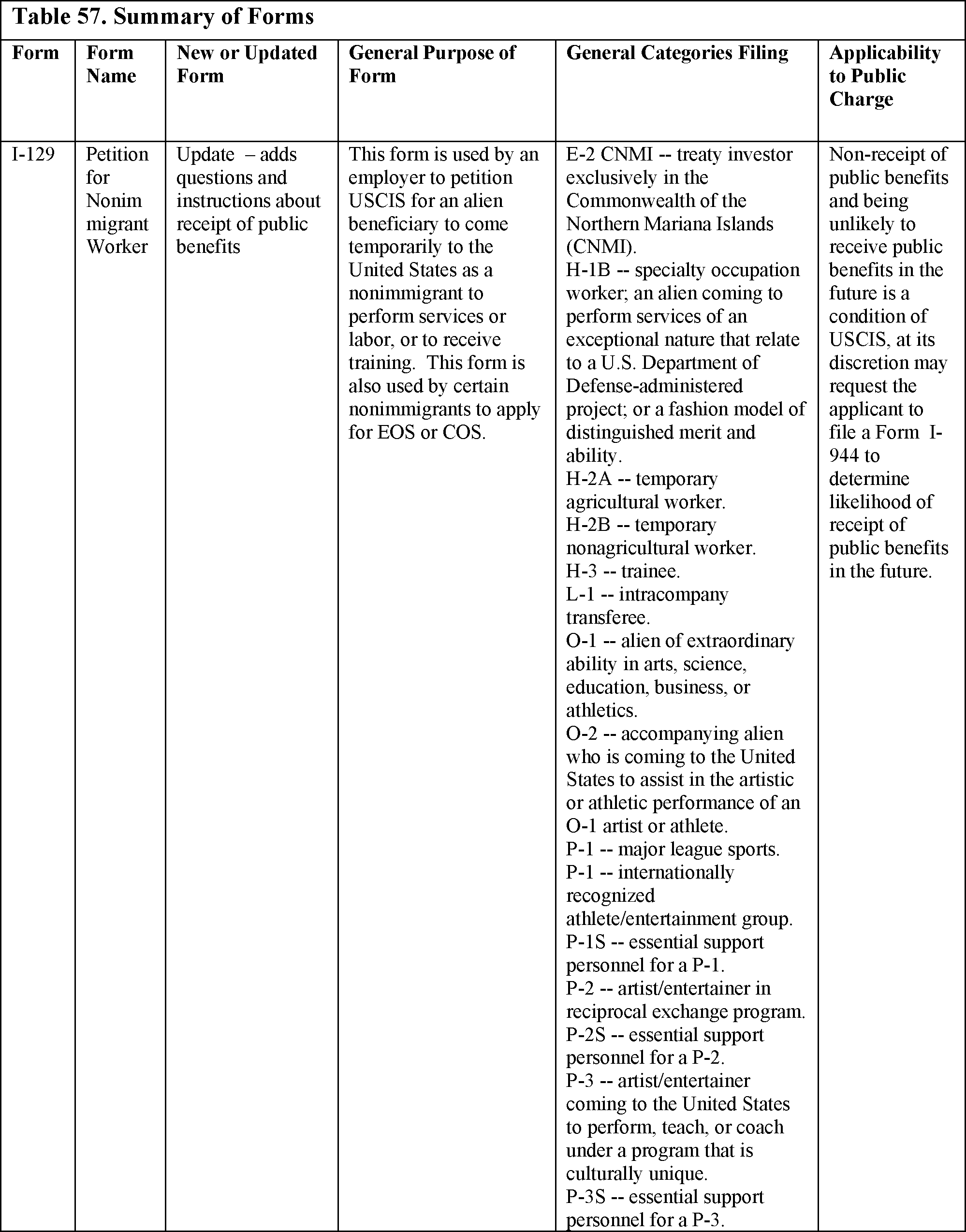

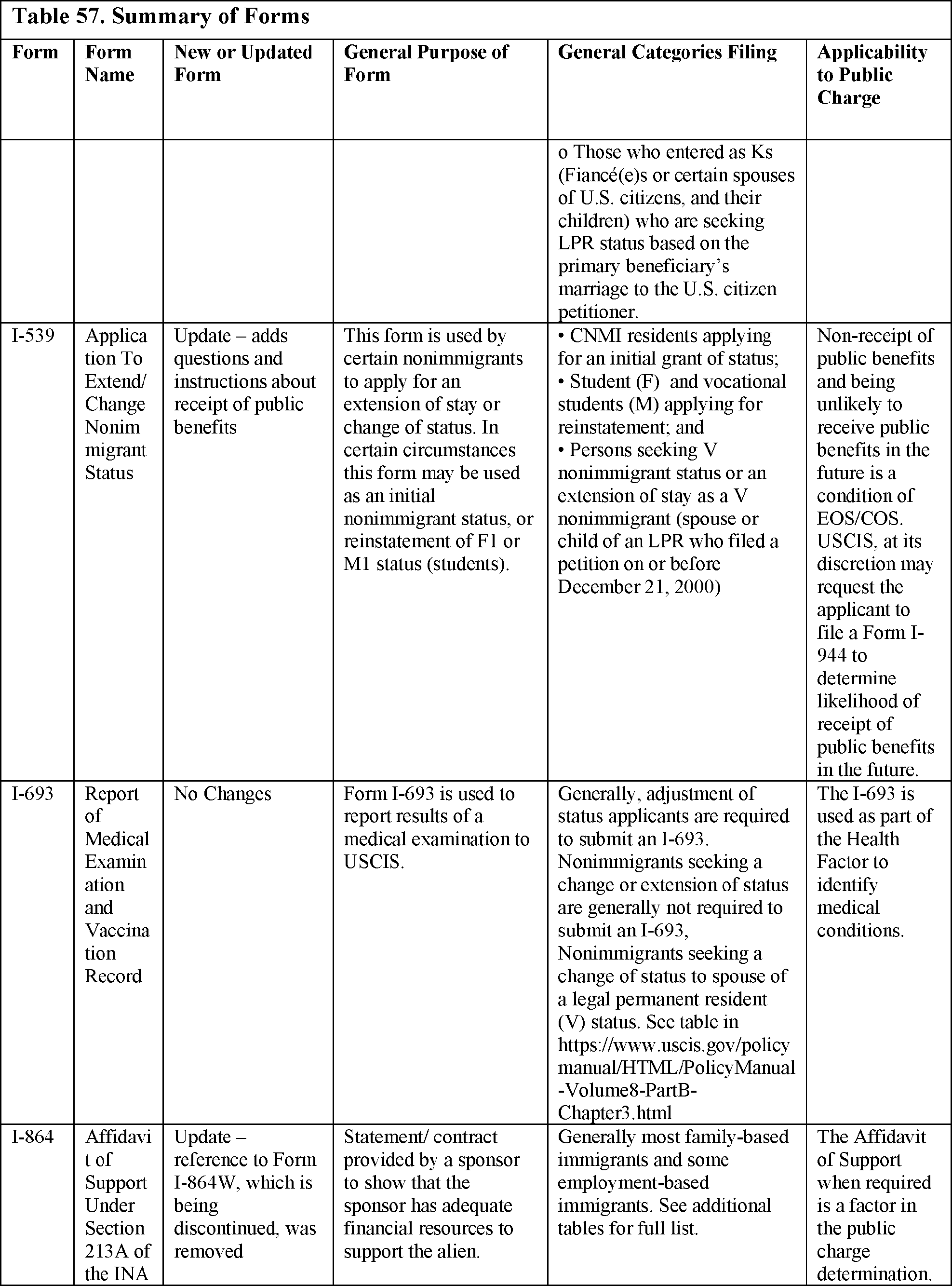

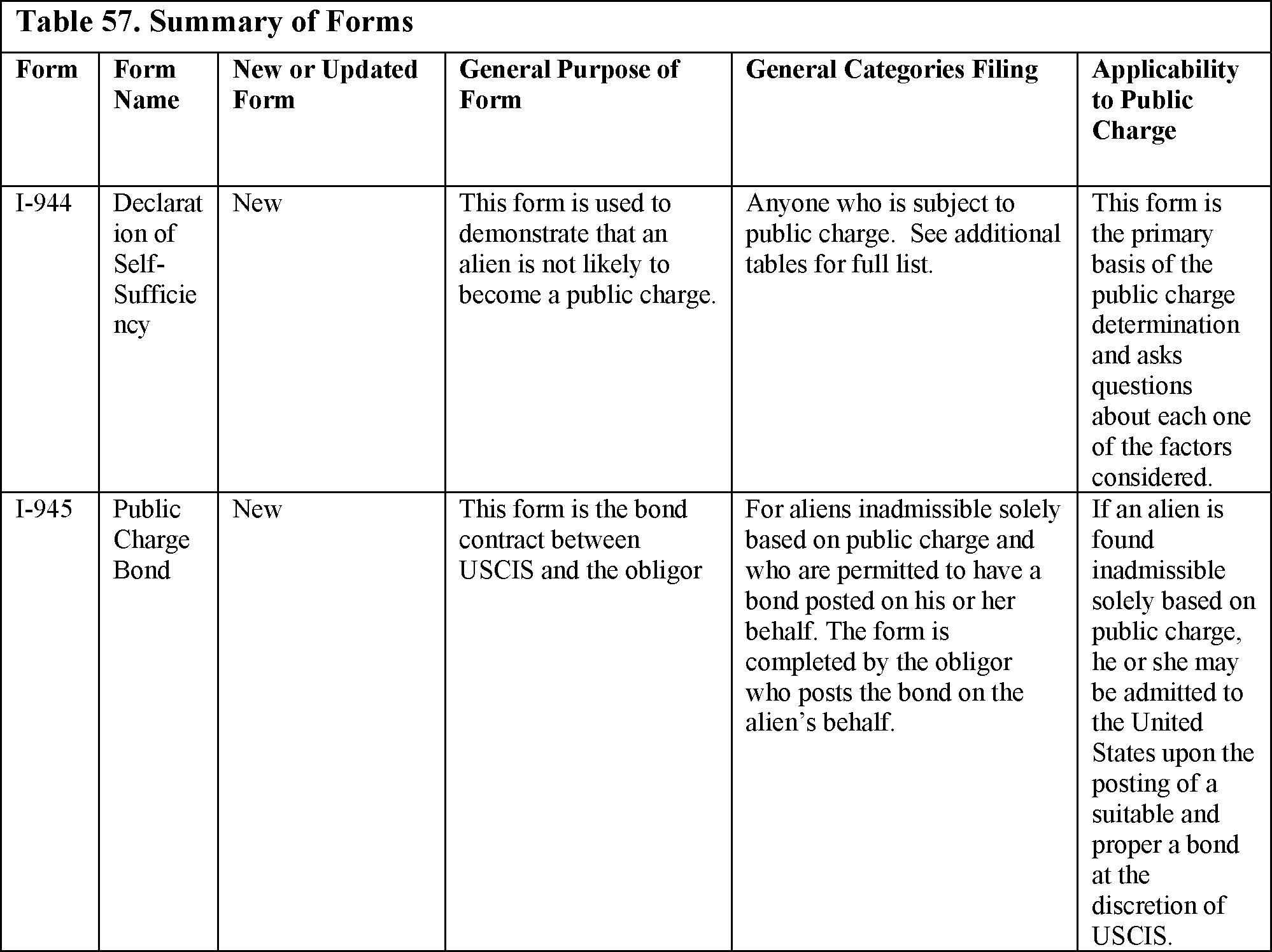

Table 1 provides a more detailed summary of the proposed provisions and their impacts.

Start Printed Page 51119

Start Printed Page 51120

Start Printed Page 51121

Start Printed Page 51122

III. Purpose of the Proposed Rule

A. Self-Sufficiency

DHS seeks to better ensure that applicants for admission to the United States and applicants for adjustment of status to lawful permanent resident who are subject to the public charge ground of inadmissibility are self-sufficient, i.e., do not depend on public resources to meet their needs, but rather rely on their own capabilities and the resources of their family, sponsor, and private organizations.[]

Under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), an alien is inadmissible if, at the time of an application for a visa, admission, or adjustment of status, he or she is likely at any time to become a public charge. The statute requires DHS to consider the following minimum factors that reflect the likelihood that an alien will become a public charge: The alien's age; health; family status; assets, resources, and financial status; and education and skills. DHS may also consider any affidavit of support submitted by the alien's sponsor and any other factor relevant to the likelihood of the alien becoming a public charge.

As noted in precedent administrative decisions, determining the likelihood of an alien becoming a public charge involves “consideration of all the factors bearing on the alien's ability or potential ability to be self-supporting.” []

These decisions, in general, conclude that an alien who is incapable of earning a livelihood, who does not have sufficient funds in the United States for support, and who has no person in the United States willing and able to assure the alien will not need public support generally is inadmissible as likely to become a public charge.[]

Furthermore, the following congressional policy statements relating to self-sufficiency, immigration, and public benefits inform DHS's proposed administration of Start Printed Page 51123section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4).

(1) Self-sufficiency has been a basic principle of United States immigration law since this country's earliest immigration statutes.

(2) It continues to be the immigration policy of the United States that—

(A) Aliens within the Nation's borders not depend on public resources to meet their needs, but rather rely on their own capabilities and the resources of their families, their sponsors, and private organizations; and

(B) The availability of public benefits not constitute an incentive for immigration to the United States.[]

Within this administrative and legislative context, DHS's view of self-sufficiency is that aliens subject to the public charge ground of inadmissibility must rely on their own capabilities and secure financial support, including from family members and sponsors, rather than seek and receive public benefits to meet their needs. Aliens subject to the public charge ground of inadmissibility include: Immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, fiancé(e)s, family-preference immigrants, most employment-based immigrants, diversity visa immigrants, and certain nonimmigrants. Most employment-based immigrants are coming to work for their petitioning employers; DHS believes that by virtue of their employment, such immigrants should have adequate income and resources to support themselves without resorting to seeking public benefits. Similarly, DHS believes that, consistent with section 212(a)(4), nonimmigrants should have sufficient financial means or employment, if authorized to work, to support themselves for the duration of their authorized admission and temporary stay. In addition, immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, fiancé(e)s, most family-preference immigrants, and some employment-based immigrants require a sponsor and a legally binding affidavit of support under section 213A of the Act showing that the sponsor agrees to provide support to maintain the alien at an annual income that is not less than 125 percent of the FPG.[]

DHS's view of self-sufficiency also informs other aspects of this proposal. DHS proposes that aliens who seek to change their nonimmigrant status or extend their nonimmigrant stay generally should also be required to continue to be self-sufficient and not remain in the United States to avail themselves of any public benefits for which they are eligible, even though the public charge inadmissibility determination does not directly apply to them. Such aliens should have adequate financial resources to maintain the status they seek to extend or to which they seek to change for the duration of their temporary stay, and must be able to support themselves.

B. Public Charge Inadmissibility Determinations

DHS seeks to interpret the term “public charge” for purposes of making public charge inadmissibility determinations. As noted above, Congress codified the minimum mandatory factors that must be considered as part of the public charge inadmissibility determination under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4): Age, health, family status, assets, resources, financial status, education, and skills.[]

In addition to these minimum factors, the statute states that any affidavit of support under section 213A of the Act may also be considered.[]

In fact, since an affidavit of support is required for family-sponsored immigrant applicants and certain employment-sponsored immigrant applicants, these aliens are inadmissible as likely to become a public charge if they do not submit such a sufficient affidavit of support.[]

Although INS []

issued a proposed rule and Interim Field Guidance in 1999, neither the proposed rule nor Interim Field Guidance sufficiently described the mandatory factors or explained how to weigh these factors in the public charge inadmissibility determination.[]

The 1999 Interim Field Guidance allows consideration of the receipt of cash public benefits when determining whether an applicant meets the definition of “public charge,” but excluded consideration of non-cash public benefits. In addition, the 1999 Interim Field Guidance placed its emphasis on primary dependence on cash public benefits. This proposed rule would improve upon the 1999 Interim Field Guidance by removing the artificial distinction between cash and non-cash benefits, and aligning public charge policy with the self-sufficiency principles set forth in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA).[]

The proposed rule would provide clarification and guidance on the mandatory factors, including how these factors would be evaluated in relation to the new proposed definition of public charge and in making a public charge inadmissibility determination.[]

IV. Background

Three principal issues []

have framed the development of public charge inadmissibility: (1) The factors involved in determining whether or not an alien is likely to become a public charge, (2) the relationship between public charge and receipt of public benefits, and (3) the consideration of a sponsor's affidavit of support within public charge inadmissibility determinations.

Start Printed Page 51124

A. Legal Authority

DHS's authority for making public charge inadmissibility determinations and related decisions is found in several statutory provisions. Section 102 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Pub. L. 107-296, 116 Stat. 2135), 6 U.S.C. 112, and section 103 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA, or the Act), 8 U.S.C. 1103, charge the Secretary with the administration and enforcement of the immigration and naturalization laws of the United States. In addition to establishing the Secretary's general authority for the administration and enforcement of immigration laws, section 103 of the Act enumerates various related authorities including the Secretary's authority to establish regulations and prescribe such forms of bond as are necessary for carrying out her authority. Section 212 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182, establishes classes of aliens that are ineligible for visas, admission, or adjustment of status and paragraph (a)(4) of that section establishes the public charge ground of inadmissibility, including the minimum factors the Secretary must consider in making a determination that an alien is likely to become a public charge. Section 212(a)(4) of the Act also establishes the affidavit of support requirement as applicable to certain family-based and employment-based immigrants, and exempts certain aliens from both the public charge ground of inadmissibility and the affidavit of support requirement. Section 213 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1183, provides the Secretary with discretion to admit into United States an alien who is determined to be inadmissible as a public charge under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, but is otherwise admissible, upon the giving of a proper and suitable bond. That section authorizes the Secretary to establish the amount and conditions of such bond. Section 213A of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1183a, sets out requirements for the sponsor's affidavit of support, including reimbursement of government expenses where the sponsored alien received means-tested public benefits. Section 214 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1184, addresses requirements for the admission of nonimmigrants, including authorizing the Secretary to prescribe the conditions of such admission through regulations and when necessary establish a bond to ensure that those admitted as nonimmigrants or who change their nonimmigrant status under section 248 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1258, depart if they violate their nonimmigrant status or after such status expires. Section 245 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1255, generally establishes eligibility criteria for adjustment of status to lawful permanent residence. Section 248 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1258, authorizes the Secretary to prescribe conditions under which an alien may change his or her status from one nonimmigrant classification to another. The Secretary proposes the changes in this rule under these authorities.

B. Immigration to the United States

The INA governs whether an alien may obtain a visa, be admitted to or remain in the United States, or obtain an extension of stay, change of status, or adjustment of status.[]

The INA establishes separate processes for aliens seeking a visa, admission, change of status, and adjustment of status. For example, where an immigrant visa petition is required, USCIS will adjudicate the petition. If USCIS approves the petition, the alien may apply for a visa with the U.S. Department of State (DOS) and thereafter seek admission in the appropriate immigrant classification. If the alien is present in the United States, he or she may be eligible to apply to USCIS for adjustment of status to that of a lawful permanent resident. In the nonimmigrant context, the nonimmigrant typically applies directly to the U.S. consulate or embassy abroad for a visa to enter for a limited purpose, such as to visit for business or tourism.[]

Applicants for admission are inspected at or, when encountered, between the port of entry. The inspection is conducted by immigration officers in a timeframe and setting distinct from the visa adjudication process. If a nonimmigrant alien is present in the United States, he or she may be eligible to apply to USCIS for an extension of nonimmigrant stay or change of nonimmigrant status.

DHS has the discretion to waive certain grounds of inadmissibility as designated by Congress. Where an alien is seeking an immigration benefit that is subject to a ground of inadmissibility, DHS cannot approve the immigration benefit being sought if a waiver of that ground is unavailable under the INA, the alien does not meet the statutory and regulatory requirements for the waiver, or the alien does not warrant the waiver in any authorized exercise of discretion.

C. Extension of Stay and Change of Status

Pursuant to section 214(a)(1) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1184(a)(1), DHS permits certain nonimmigrants to remain in the United States beyond their current period of authorized stay to continue engaging in activities permitted under their current nonimmigrant status. The extension of stay regulations require a nonimmigrant applying for an extension of stay to demonstrate that he or she is admissible to the United States.[]

For some extension of stay applications, the applicant's financial status is an element of the eligibility determination.[]

DHS has the authority to set conditions in determining whether to grant the extension of stay request.[]

The decision to grant an extension of stay application, with certain limited exceptions, is discretionary.[]

Under section 248 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1258, DHS may permit an alien to change his or her status from one nonimmigrant status to another nonimmigrant status, with certain exceptions, as long as the nonimmigrant is continuing to maintain his or her current nonimmigrant status and is not inadmissible under section 212(a)(9)(B)(i) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(9)(B)(i).[]

An applicant's financial status is currently part of the determination for changes to certain nonimmigrant classifications.[]

Like extensions of stay, change of status adjudications are discretionary determinations, and DHS has the authority to set conditions that apply for a nonimmigrant to change his or her status.[]

D. Public Charge Inadmissibility

Section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), provides that an alien applicant for a visa, admission, or adjustment of status is inadmissible if he or she is likely at any time to become a public charge. The public charge ground of inadmissibility, therefore, applies to any alien applying for a visa to come to the United States temporarily or permanently, for admission, or for Start Printed Page 51125adjustment of status to that of a lawful permanent resident.[]

Section 212(a)(4) of the Act, does not, however, directly apply to applications for extension of stay or change of status because extension of stay and change of status applications are not applications for a visa, admission, or adjustment of status.

The INA does not define public charge. It does, however, specify that when determining if an alien is likely at any time to become a public charge, consular officers and immigration officers must, at a minimum, consider the alien's age; health; family status; assets, resources, and financial status; and education and skills.[]

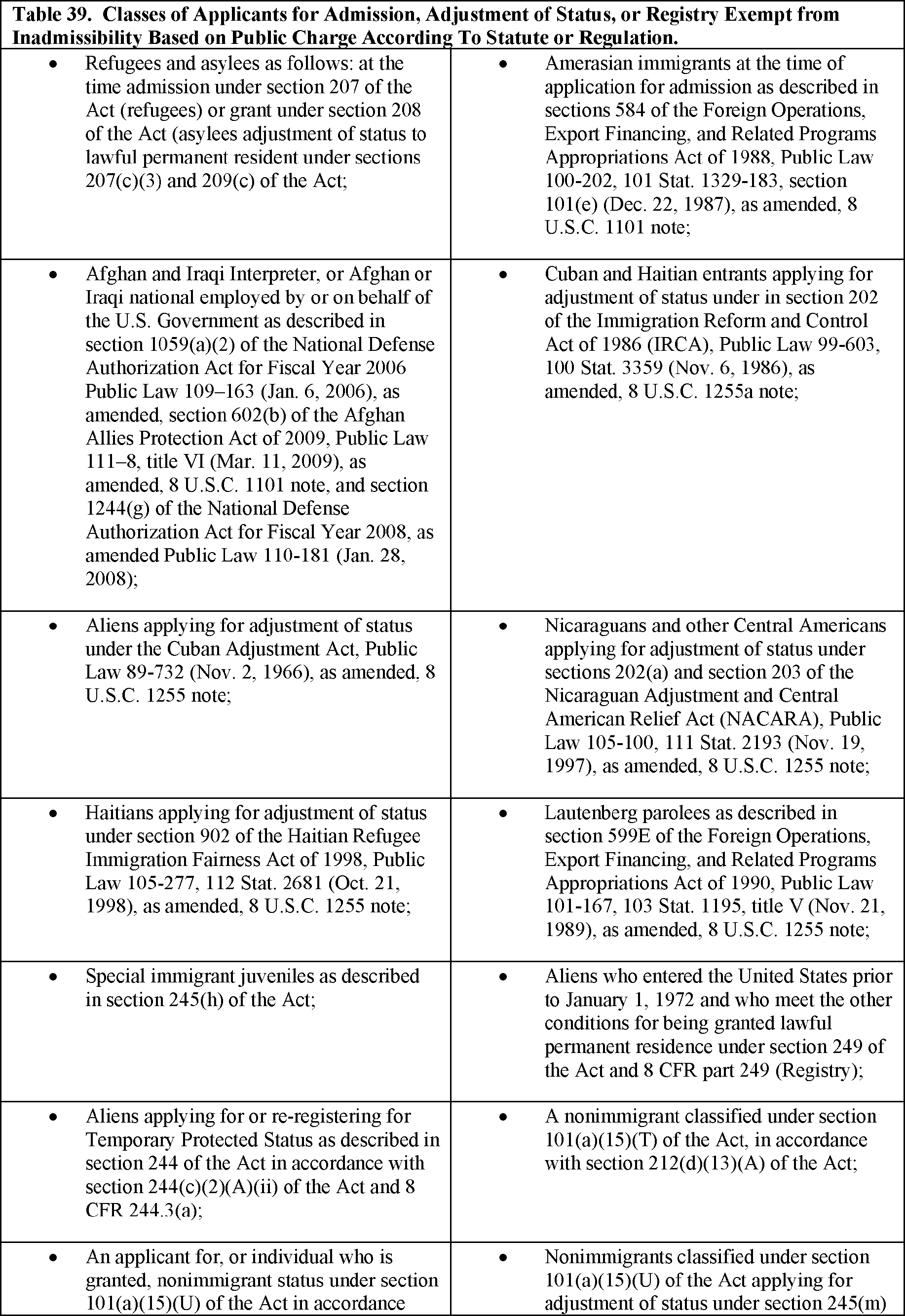

Some immigrant and nonimmigrant categories are exempt from the public charge inadmissibility ground. DHS proposes to list these categories in the regulation. DHS also proposes to list in the regulation the applicants that the law permits to apply for a waiver of the public charge inadmissibility ground.[]

Additionally, section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), permits the consular officer or the immigration officer to consider any affidavit of support submitted under section 213A of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1183a, on the applicant's behalf when determining whether the applicant may become a public charge.[]

In fact, with very limited exceptions, aliens seeking family-based immigrant visas and adjustment of status, and a limited number of employment-based immigrant visas or adjustment of status, must have a sufficient affidavit of support or will be found inadmissible as likely to become a public charge.[]

In general, an alien whom DHS has determined to be inadmissible based on the public charge ground may, if otherwise admissible, be admitted at the discretion of the Secretary upon giving a suitable and proper bond or undertaking approved by the Secretary.[]

The purpose of issuing a public charge bond is to ensure that the alien will not become a public charge in the future.[]

Since the introduction of enforceable affidavits of support in section 213A of the Act, the use of public charge bonds has decreased and USCIS does not currently have a public charge bond process.[]

This rule would outline a process under which USCIS could, in its discretion, offer public charge bonds to applicants for adjustment of status who are inadmissible only on public charge grounds.

1. Public Laws and Case Law

Since at least 1882, the United States has denied admission to aliens on public charge grounds.[]

The INA of 1952 excluded aliens who, in the opinion of the consular officer at the time of application for a visa, or in the opinion of the Government at the time of application for admission, are likely at any time to become public charges.[]

The Government has long interpreted the words “in the opinion of” as evincing the subjective nature of the determination.[]

A series of administrative decisions after passage of the Act clarified that a totality of the circumstances review was the proper framework for making public charge determinations and that receipt of welfare would not, alone, lead to a finding of likelihood of becoming a public charge. In Matter of Martinez-Lopez, the Attorney General opined that the statute “require[d] more than a showing of a possibility that the alien will require public support. Some specific circumstance, such as mental or physical disability, advanced age, or other fact showing that the burden of supporting the alien is likely to be cast on the public, must be present. A healthy person in the prime of life cannot ordinarily be considered likely to become a public charge, especially where he has friends or relatives in the United States who have indicated their ability and willingness to come to his assistance in case of emergency.” []

In Matter of Perez, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) held that “[t]he determination of whether an alien is likely to become a public charge . . . is a prediction based upon the totality of the alien's circumstances at the time he or she applies for an immigrant visa or admission to the United States. The fact that an alien has been on welfare does not, by itself, establish that he or she is likely to become a public charge.” []

As stated in Matter of Harutunian,[]

public charge determinations should take into consideration factors such as an alien's age, incapability of earning a livelihood, a lack of sufficient funds for self-support, and a lack of persons in this country willing and able to assure that the alien will not need public support.

The totality of circumstances approach to public charge inadmissibility determinations was codified in relation to one specific class of aliens in the 1980s. In 1986, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), providing eligibility for lawful status to certain aliens who had resided in the United States continuously prior to January 1, 1982.[]

No changes were made to the language of the public charge exclusion ground under former section 212(a)(15) of the Act, but IRCA contained special public charge rules for aliens seeking legalization under 245A of the Act. Although IRCA provided otherwise eligible aliens an exemption or waiver for some grounds of excludability, the aliens generally remained excludable on public charge grounds.[]

Under IRCA, however, if an applicant demonstrated a history of self-support through employment and without receiving public cash assistance, he or she would not be ineligible for adjustment of status on public charge grounds.[]

In addition, aliens who were “aged, blind or disabled” as defined in section 1614(a)(1) of the Social Security Act, could obtain a waiver from the public charge provision.[]

Start Printed Page 51126

INS promulgated 8 CFR 245a.3,[]

which established that immigration officers would make public charge determinations by examining the “totality of the alien's circumstances at the time of his or her application for legalization.” []

According to the regulation, the existence or absence of a particular factor could never be the sole criterion for determining whether a person is likely to become a public charge.[]

Further, the regulation established that the determination is a “prospective evaluation based on the alien's age, health, income, and vocation.” []

A special provision in the rule stated that aliens with incomes below the poverty level are not excludable if they are consistently employed and show the ability to support themselves.[]

Finally, an alien's past receipt of public cash assistance would be a significant factor in a context that also considers the alien's consistent past employment.[]

In Matter of A-,[]

INS again pursued a totality of circumstances approach in public charge determinations. “Even though the test is prospective,” INS “considered evidence of receipt of prior public assistance as a factor in making public charge determinations.” INS also considered an alien's work history, age, capacity to earn a living, health, family situation, affidavits of support, and other relevant factors in their totality.[]

The administrative practices surrounding public charge inadmissibility determinations began to crystalize into legislative changes in the 1990s. The Immigration Act of 1990 reorganized section 212(a) of the Act and re-designated the public charge provision as section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4).[]

In 1996, PRWORA []

and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) []

altered the legislative landscape of public charge considerably.[]

Through PRWORA, which is commonly known as the 1996 welfare reform law, Congress declared that aliens generally should not depend on public resources and that these resources should not constitute an incentive for immigration to the United States.[]

Congress also created section 213A of the Act and made a sponsor's affidavit of support for an alien beneficiary legally enforceable.[]

The affidavit of support provides a mechanism for public benefit granting agencies to seek reimbursement in the event a sponsored alien received means-tested public benefits.[]

2. Public Benefits Under PRWORA

PRWORA also significantly restricted alien eligibility for many Federal, State, and local public benefits.[]

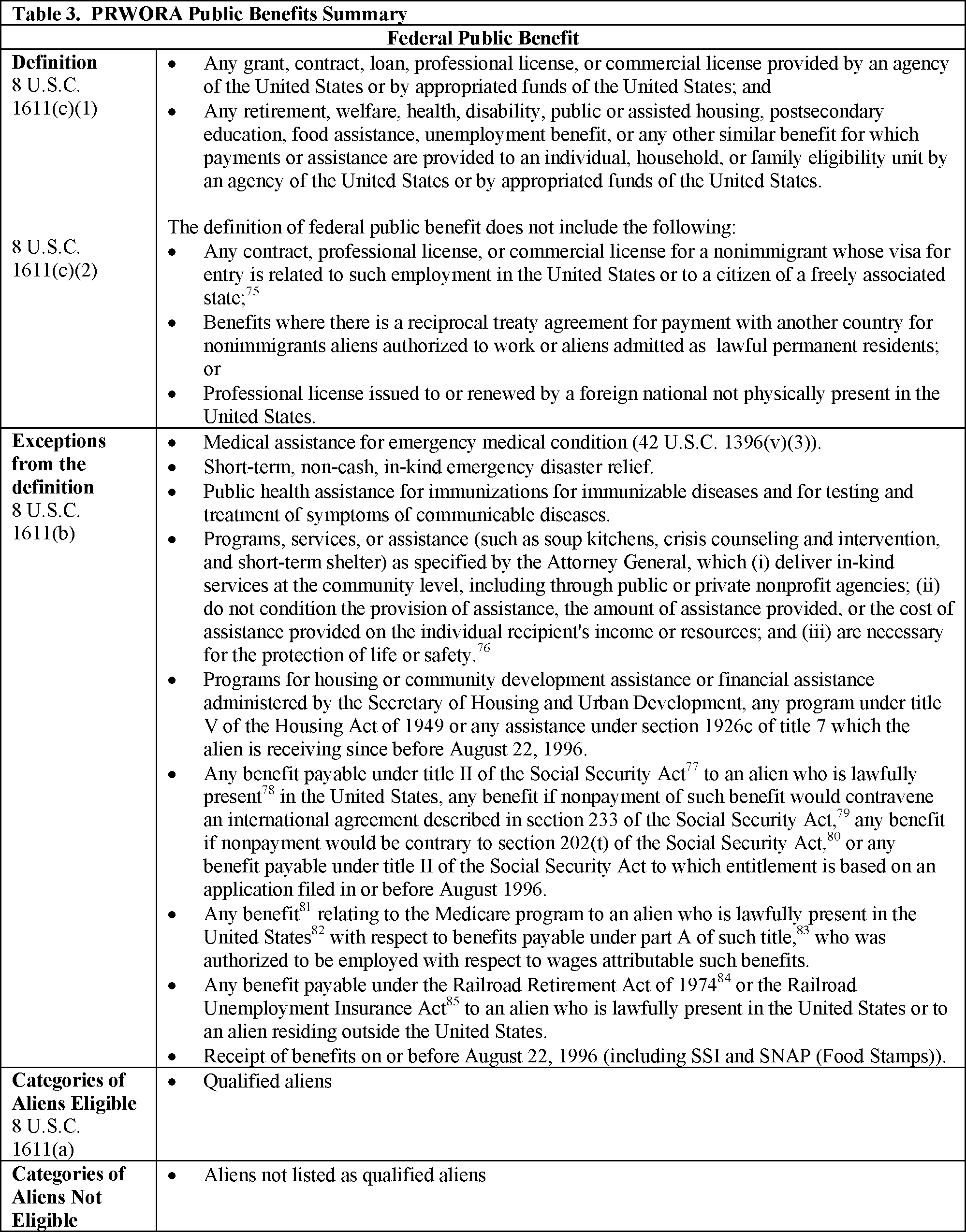

With certain exceptions, Congress defined the term “Federal public benefit” broadly as:

(A) Any grant, contract, loan, professional license, or commercial license provided by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States; and

(B) Any retirement, welfare, health, disability, public or assisted housing, postsecondary education, food assistance, unemployment benefit, or any other similar benefit for which payments or assistance are provided to an individual, household, or family eligibility unit by an agency of the United States or by appropriated funds of the United States.[]

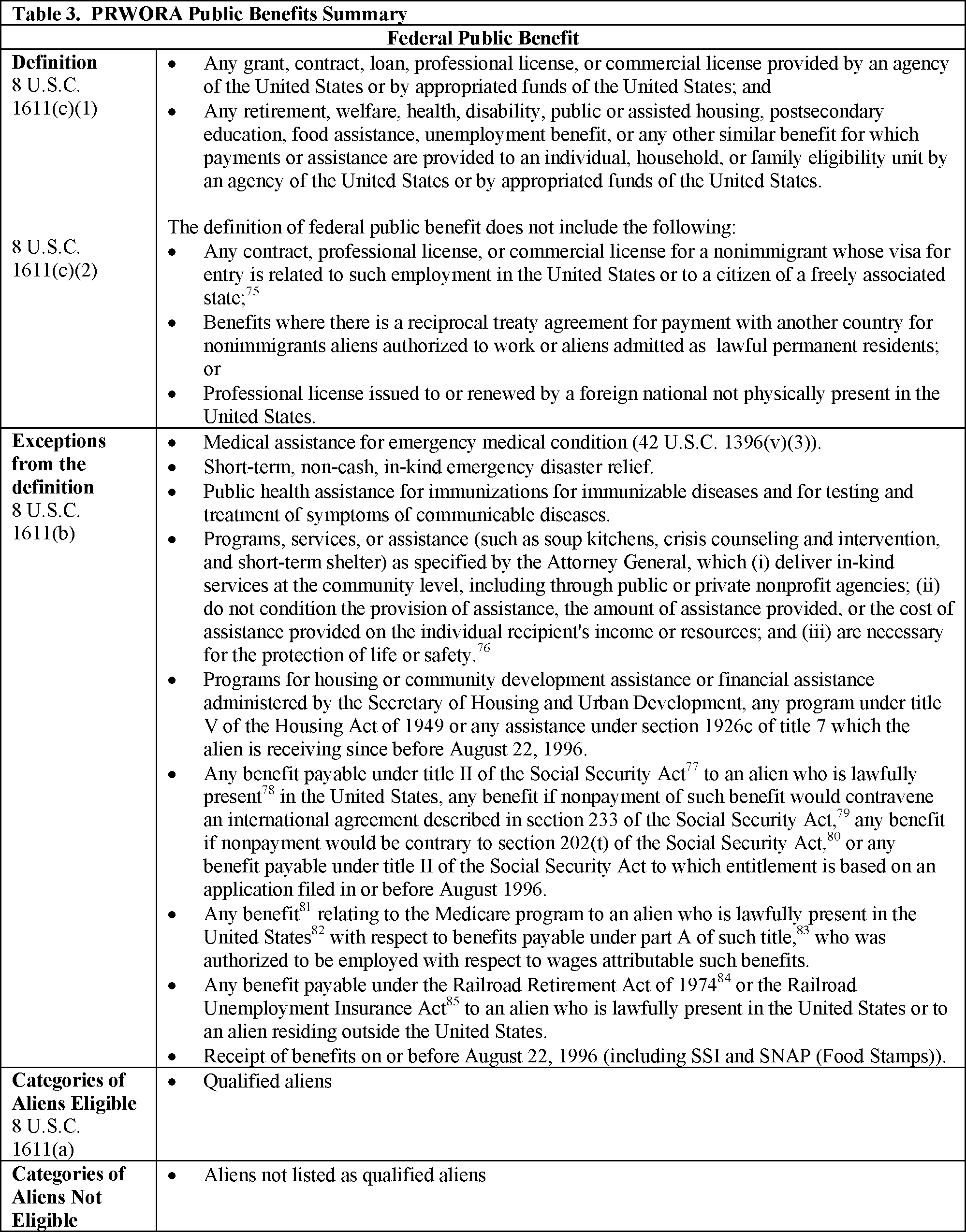

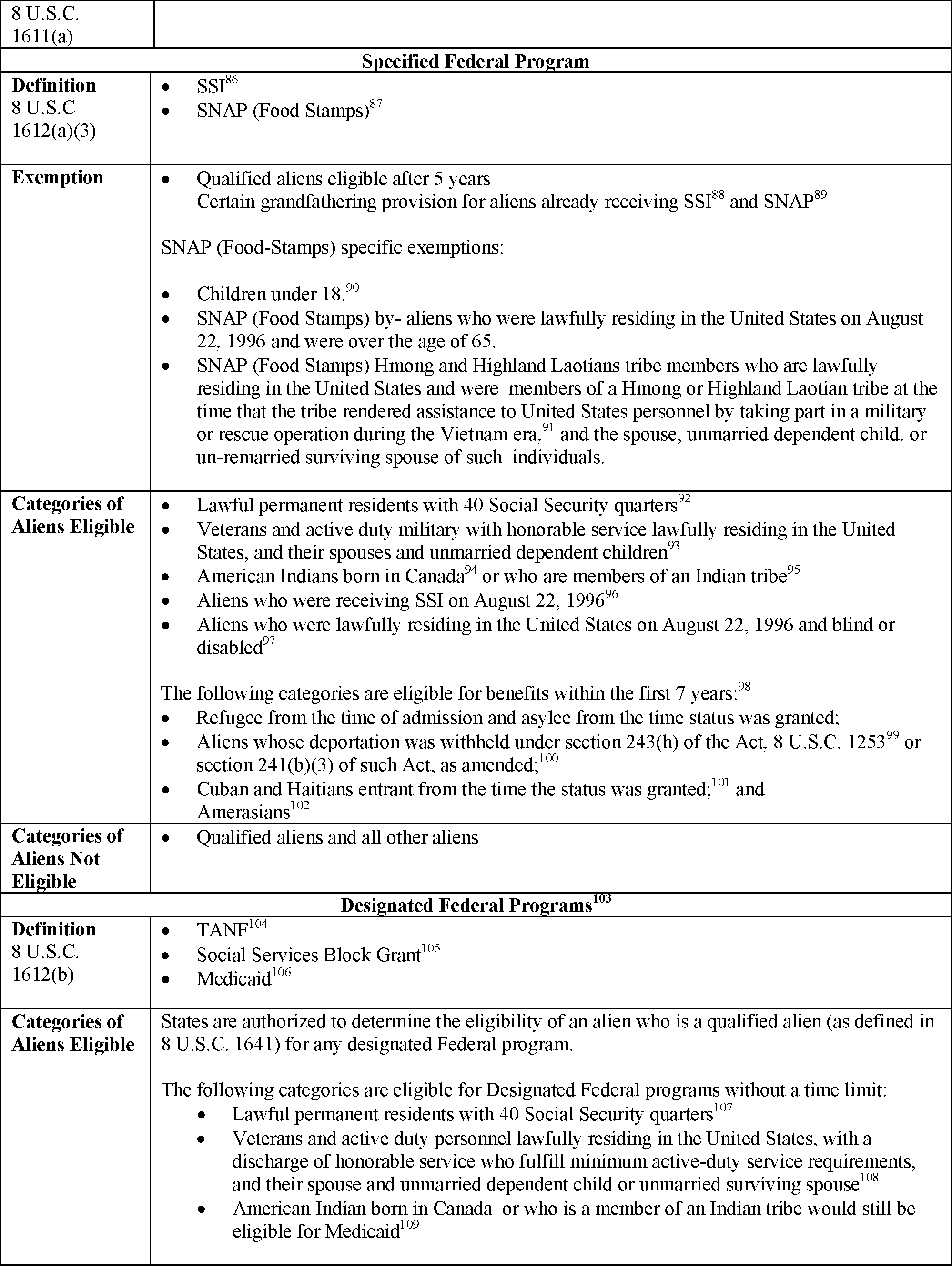

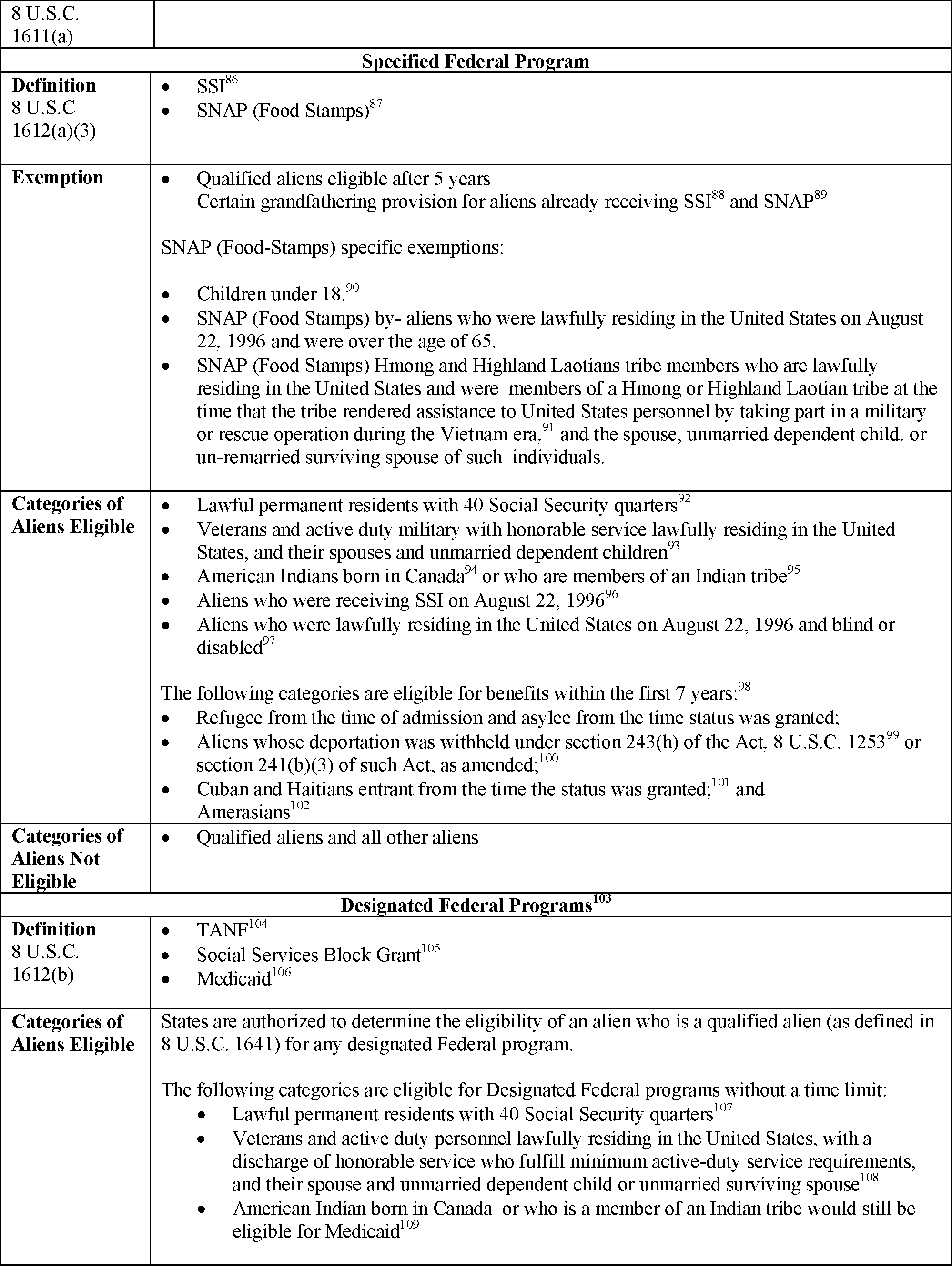

(a) Qualified Aliens

Generally, under PRWORA, “qualified aliens” are eligible for federal means-tested benefits after 5 years and are not eligible for “specified federal programs,” and states are allowed to determine whether the qualified alien is eligible for “designated federal programs.” []

The following table provides a list of immigration categories that are qualified aliens under PRWORA.[]

Start Printed Page 51127

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 further provided that an alien who is a victim of a severe form of trafficking in persons, or an alien classified as a nonimmigrant under section 101(a)(15)(T)(ii) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(15)(T)(ii), is eligible for benefits and services under any Federal or State program or activity funded or administered by any official or agency.[]

These individuals are generally exempt from the public charge inadmissibility ground.[]

With certain exceptions, aliens who were not “qualified aliens,” including nonimmigrants and unauthorized aliens, were generally barred from obtaining Federal benefits.[]

In addition to the federal public benefits definitions, PRWORA categorizes the benefits into the following categories:

- Specified Federal Programs;

- Designated Federal Programs; and

- Federal Means-Tested Benefits.

The following tables provide a summary of the definition of federal public benefit and the three categories of public benefits under PRWORA as applicable to aliens and qualified aliens.

Start Printed Page 51128

Start Printed Page 51129

Start Printed Page 51130

Congress chose not to restrict eligibility for certain benefits, including Start Printed Page 51131emergency medical assistance; short-term, in-kind, non-cash emergency disaster relief; and public health assistance related to immunizations and treatment of the symptoms of a communicable disease.[]

PRWORA defined the term “State or local public benefit” in broad terms except where the term encroached upon the definition of Federal public benefit.[]

With certain exceptions for qualified aliens, nonimmigrants, or parolees, PRWORA also limited aliens' ability to obtain certain State and local public benefits.[]

Under PRWORA, States may enact their own legislation to provide public benefits to certain aliens not lawfully present in the United States.[]

PRWORA also provided that a State that chooses to follow the Federal “qualified alien” definition in determining aliens' eligibility for public assistance “shall be considered to have chosen the least restrictive means available for achieving the compelling governmental interest of assuring that aliens be self-reliant in accordance with national immigration policy.” []

Still, some States and localities have funded public benefits (particularly medical and nutrition benefits) that aliens may be not eligible for federally.[]

While PRWORA allows both qualified aliens and non-qualified aliens to receive certain benefits (e.g., emergency benefits (all aliens); SNAP (qualified alien children under 18)), Congress did not exempt the receipt of such benefits from consideration for purposes of INA section 212(a)(4).” []

Therefore, DHS may take into consideration for purposes of a public charge determination, receipt of public benefits even if an alien may receive such benefits under PRWORA.

(b) Public Benefits Exempt Under PRWORA

Although PRWORA provided a broad definition of public benefits that only qualified aliens are eligible to receive,[]

it also made certain public benefits available even to non-qualified aliens.[]

Congress excluded certain benefits, such as contracts, professional licenses, and commercial licenses from the “federal public benefit” definition.[]

In addition, Congress further provided that the following public benefits are available to all aliens, regardless of whether an individual is a qualified alien: []

- Medical assistance under title XIX of the Social Security Act [42 U.S.C. 1396 et seq.] (or any successor program to such title) for care and services that are necessary for the treatment of an emergency medical condition (as defined in section 1903(v)(3) of such Act [42 U.S.C. 1396b(v)(3)]) of the alien involved and are not related to an organ transplant procedure, if the alien involved otherwise meets the eligibility requirements for medical assistance under the State plan approved under such title (other than the requirement of the receipt of aid or assistance under title IV of such Act [42 U.S.C. 601 et seq.], supplemental security income benefits under title XVI of such Act [42 U.S.C. 1381 et seq.], or a State supplementary payment).

- Short-term, non-cash, in-kind emergency disaster relief.[]

- Public health assistance (not including any assistance under title XIX of the Social Security Act [42 U.S.C. 1396 et seq.]) for immunizations with respect to immunizable diseases and for testing and treatment of symptoms of communicable diseases whether or not such symptoms are caused by a communicable disease.

- Programs, services, or assistance (such as soup kitchens, crisis counseling and intervention, and short-term shelter) specified by the Attorney General, in the Attorney General's sole and unreviewable discretion after consultation with appropriate Federal agencies and departments, which (i) deliver in-kind services at the community level, including through public or private nonprofit agencies; (ii) do not condition the provision of assistance, the amount of assistance provided, or the cost of assistance Start Printed Page 51132provided on the individual recipient's income or resources; and (iii) are necessary for the protection of life or safety.

- Programs for housing or community development assistance or financial assistance administered by the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, any program under title V of the Housing Act of 1949 [42 U.S.C. 1471 et seq.], or any assistance under section 1926c of title 7, to the extent that the alien is receiving such a benefit on August 22, 1996.

These benefits, which are described in 8 U.S.C. 1611(b), were further clarified by the Department of Justice and some of the agencies that administer these public benefits. On January 16, 2001, the Department of Justice published a notice of final order, “Final Specification of Community Programs Necessary for Protection of Life or Safety Under Welfare Reform Legislation,” []

which indicated that PRWORA does not preclude aliens from receiving police, fire, ambulance, transportation (including paratransit), sanitation, and other regular, widely available services programs, services, or assistance. In addition, the notice provided for a three-part test in identifying excluded benefits and services for the protection of life and safety. Specified programs must satisfy all three prongs of this test:

1. The government-funded programs, services, or assistance specified are those that: Deliver in-kind (non-cash) services at the community level, including through public or private non-profit agencies or organizations; do not condition the provision, amount, or cost of the assistance on the individual recipient's income or resources; and serve purposes of the type described in the list below, for the protection of life or safety.

2. The community-based programs, services, or assistance are limited to those that provide in-kind (non-cash) benefits and are open to individuals needing or desiring to participate without regard to income or resources. Programs, services, or assistance delivered at the community level, even if they serve purposes of the type described, are not within this specification if they condition on the individual recipient's income or resources: (a) The provision of assistance; (b) the amount of assistance provided; or (c) the cost of the assistance provided on the individual recipient's income or resources.

3. Included within the specified programs, services, or assistance determined to be necessary for the protection of life or safety are the following types of programs:

- Crisis counseling and intervention programs; services and assistance relating to child protection, adult protective services, violence and abuse prevention, victims of domestic violence or other criminal activity; or treatment of mental illness or substance abuse;

- Short-term shelter or housing assistance for the homeless, for victims of domestic violence, or for runaway, abused, or abandoned children;

- Programs, services, or assistance to help individuals during periods of heat, cold, or other adverse weather conditions;

- Soup kitchens, community food banks, senior nutrition programs such as meals on wheels, and other such community nutritional services for persons requiring special assistance;

- Medical and public health services (including treatment and prevention of diseases and injuries) and mental health, disability, or substance abuse assistance necessary to protect life or safety;

- Activities designed to protect the life or safety of workers, children and youths, or community residents; and

- Any other programs, services, or assistance necessary for the protection of life or safety.

In congressional debates leading up to the passage of IIRIRA, Senator Kennedy stated that “[t]hese benefit all, because they relate to the public health and are in the public interest. Where the public interest is not served, we should not provide the public assistance to illegal immigrants.” []

Therefore, these benefits were provided to all aliens including illegal aliens. These benefits would not be part of the public charge determination under the proposed rule.[]

3. Changes Under IIRIRA

Under IIRIRA,[]

the public charge inadmissibility statute changed significantly. IIRIRA codified the following minimum factors that must be considered when making public charge determinations: []

- Age;

- Health;

- Family status;

- Assets, resources, and financial status; and

- Education and skills.[]

Congress also generally permitted but did not require consular and immigration officers to consider an enforceable affidavit of support as a factor in the determination of inadmissibility,[]

except in certain cases where an affidavit of support is required and must be considered at least in that regard.[]

The law required affidavits of support for most family-based immigrants and certain employment-based immigrants and provided that these aliens are inadmissible unless a satisfactory affidavit of support is filed on their behalf.[]

In the Conference Report, the committee indicated that the amendments to INA section 212(a)(4), 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), were designed to expand the public charge ground of inadmissibility.[]

The report indicated that self-reliance is one of the fundamental principles of immigration law and aliens should have affidavits of support executed.[]

DHS believes that the policy goals articulated in PRWORA and IIRIRA should inform its administrative implementation of the public charge ground of inadmissibility. There is no tension between the availability of public benefits to some aliens as set forth in PRWORA and Congress's intent to deny visa issuance, admission, and adjustment of status to aliens who are likely to become a public charge. Indeed, Congress, in enacting PRWORA and IIRIRA very close in time, must have recognized that it made certain public benefits available to some aliens who are also subject to the public charge grounds of inadmissibility, even though receipt of such benefits could render the alien inadmissible as likely to become a public charge.Start Printed Page 51133

Under the carefully devised scheme envisioned by Congress, aliens generally would not be issued visas, admitted to the United States, or permitted to adjust status if they are likely to become public charges. This prohibition may deter aliens from making their way to the United States or remaining in the United States permanently for the purpose of availing themselves of public benefits.[]

Congress must have understood, however, that certain aliens who were unlikely to become public charges when seeking a visa, admission, or adjustment of status might thereafter reasonably find themselves in need of public benefits that, if obtained, would render them a public charge. Consequently, in PRWORA, Congress made limited allowances for that possibility. But Congress also did not correspondingly limit the applicability of the public charge statute; if an alien subsequent to receiving public benefits wished to adjust status in order to remain in the United States permanently or left the United States and later wished to return, the public charge inadmissibility consideration (naturally including consideration of receipt of public benefits) would again come into play. In other words, although an alien may obtain public benefits for which he or she is eligible, the receipt of those benefits may be considered for future public charge inadmissibility determination purposes.

4. INS 1999 Interim Field Guidance

On May 26, 1999, INS issued interim Field Guidance on Deportability and Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds.[]

This guidance identified how the agency would determine if a person is likely to become a public charge under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a), for admission and adjustment of status purposes, and whether a person is deportable as a public charge under section 237(a)(5) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1227(a)(5).[]

INS proposed promulgating these policies as regulations in a proposed rule issued on May 26, 1999.[]

DOS also issued a cable to its consular officers at that time implementing similar guidance for visa adjudications, and its Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM) was similarly updated.[]

USCIS has continued to follow the 1999 Interim Field Guidance in its adjudications, and DOS has continued following the public charge guidance set forth in the FAM.[]

In the 1999 proposed rule, INS proposed to “alleviate growing public confusion over the meaning of the currently undefined term `public charge' in immigration law and its relationship to the receipt of Federal, State, or local public benefits.” []

INS sought to reduce negative public health and nutrition consequences generated by the confusion and to provide aliens, their sponsors, health care and immigrant assistance organizations, and the public with better guidance as to the types of public benefits that INS considered relevant to the public charge determinations.[]

INS also sought to address the public's concerns about immigrants' fears of accepting public benefits for which they remained eligible, specifically in regards to medical care, children's immunizations, basic nutrition and treatment of medical conditions that may jeopardize public health. With its guidance, INS aimed to stem the fears that were causing noncitizens to refuse limited public benefits, such as transportation vouchers and child care assistance, so that they would be better able to obtain and retain employment and establish self-sufficiency.[]

INS defined public charge in its proposed rule and 1999 Interim Field Guidance to mean “the likelihood of a foreign national becoming primarily dependent []

on the government for subsistence, as demonstrated by either:

- Receipt of public cash assistance for income maintenance; or

- Institutionalization for long-term care at government expense.”

When developing the proposed rule, INS consulted with Federal benefit-granting agencies such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of Agriculture (USDA). The Deputy Secretary of HHS, which administers Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and other benefits, advised that the best evidence of whether an individual is relying primarily on the government for subsistence is either the receipt of public cash benefits for income maintenance purposes or institutionalization for long-term care at government expense.[]

The Deputy Commissioner for Disability and Income Security Programs at SSA agreed that the receipt of SSI “could show primary dependence on the government for subsistence fitting the INS definition of public charge provided that all of the other factors and prerequisites for admission or deportation have been considered or met.” []

And the USDA's Under Secretary for Food, Nutrition and Consumer Services advised that “neither the receipt of food stamps nor nutrition assistance provided under the Special Nutrition Programs administered by [USDA] should be considered in making a public charge determination.” []

While these letters supported the approach taken in the 1999 proposed rule and Interim Field Guidance, the letters specifically focused on the reasonableness of a given INS interpretation; i.e. primary dependence on the government for subsistence. The letters did not foreclose the agency adopting a different definition consistent with statutory authority.

The 1999 proposed rule provided that non-cash, supplemental and certain limited cash, special purpose benefits should not be considered for public charge purposes, in light of INS' decision to define public charge by reference to primary dependence on public benefits. Ultimately, however, INS did not publish a final rule conclusively addressing these issues.

E. Public Charge Bond

If an alien is determined to be inadmissible on public charge grounds under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), he or she may be admitted in the discretion of the Secretary of Homeland Security, if otherwise admissible, upon the giving of a suitable and proper bond.[]

Start Printed Page 51134

Historically, bond provisions started with states requiring certain amounts to assure an alien would not become a public charge.[]

Bond provisions were codified in federal immigration laws in 1903.[]

Notwithstanding codification in 1903, the acceptance of a bond posting in consideration of an alien's admission and to assure that he or she will not become a public charge apparently had its origin in federal administrative practice earlier than this date. Beginning in 1893, immigration inspectors served on Boards of Special Inquiry that reviewed exclusion cases of aliens who were likely to become public charges because the aliens lacked funds or relatives or friends who could provide support.[]

In these cases, the Board of Special Inquiry usually admitted the alien if someone could post bond or one of the immigrant aid societies would accept responsibility for the alien.[]

The present language of section 213 of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1183, has been in the law without essential variation since 1907.[]

Under section 21 of the Immigration Act of 1917, an immigration officer could admit an alien if a suitable bond was posted. In 1970, Congress amended section 213 of the Act to permit the posting of cash received by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and to eliminate specific references to communicable diseases of public health significance.[]

At that time, Congress also added, without further explanation or consideration, the phrase that any sums or other security held to secure performance of the bond shall be returned “except to the extent forfeited for violation of the terms thereof” upon termination of the bond.[]

Subsequently, IIRIRA amended the provision yet again when adding a parenthetical which clarified that a bond is provided in addition to, and not in lieu of, the affidavit of support and the deeming requirements under section 213A of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1183A.[]

Regulations implementing the public charge bond were promulgated in 1964 and 1966,[]

and are currently found at 8 CFR 103.6 and 8 CFR 213.1.

V. Discussion of Proposed Rule

This proposed rule would establish a proper nexus between public charge and receipt of public benefits by defining the terms public charge and public benefit, among other terms. DHS proposes to interpret the minimum statutory factors involved in public charge determinations and to establish a clear framework under which DHS would evaluate those factors to determine whether or not an alien is likely at any time in the future to become a public charge. DHS also proposes to clarify the role of a sponsor's affidavit of support within public charge inadmissibility determinations.

In addition, DHS proposes that certain factual circumstances would weigh heavily in favor of determining that an alien is not likely to become a public charge and other factual circumstances would weigh heavily in favor of determining that an alien is likely to become a public charge.[]

The purpose of assigning greater weight to certain factual circumstances is to provide clarity for the public and immigration officers with respect to how DHS would fulfill its statutory duty to assess public charge admissibility. Ultimately, each determination would be made in the totality of the circumstances based on consideration of the relevant factors. In addition, DHS proposes that for applications for adjustment of status, the alien would be required to submit a Form I-944.

DHS also proposes to establish a public charge bond process in the adjustment of status context, and proposes to clarify DHS's authority to set conditions for nonimmigrant extension of stay and change of status applications.

Finally, this proposed rule interprets the public charge inadmissibility ground under section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), not the public charge deportability ground under section 237(a)(5) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1227(a)(5). Department of Justice precedent decisions would continue to govern the standards regarding public charge deportability determinations.

A. Applicability, Exemptions, and Waivers

This rule would apply to any alien subject to section 212(a)(4) of the Act, 8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4), who is applying for admission to the United States or is applying for adjustment of status to that of lawful permanent resident before DHS.[]

DOS screens applicants who are subject to public charge inadmissibility grounds and who are seeking nonimmigrant or immigrant visas at consular posts worldwide. Nearly sixty percent of the 2.7 million immediate relatives, family-sponsored,[]

employment-based, and diversity visa-based immigrants who obtained lawful permanent resident status in the United States between fiscal years 2014 and 2016 consular processed immigrant visa applications overseas prior to being admitted to the United States as lawful permanent residents at a port-of-entry. Fifty-one percent of immediate relatives, ninety-two percent of family-sponsored immigrants, and ninety-eight percent of diversity visa immigrants obtained an immigrant visa at a consular post overseas before securing admission as a lawful permanent resident at a port-of-entry between fiscal years 2014 and 2016.[]

This rule also addresses eligibility for extension of stay and change of Start Printed Page 51135status.[]

Because the processes, evidentiary requirements, and nature of the stay in the United States for aliens seeking a visa, admission, extension of stay, change of status, and adjustment of status differ, DHS proposes public charge processes appropriately tailored to the benefit the alien seeks. For instance, aliens seeking adjustment of status undergo a different process than a temporary visitor for pleasure from Canada seeking admission to the United States. The length and nature of the stay of these two subsets of aliens differs significantly, as does frequency of entry. Accordingly, the processes and evidentiary requirements proposed in this rule vary in certain respects depending on the type of benefit and status an alien is seeking, as set forth below.

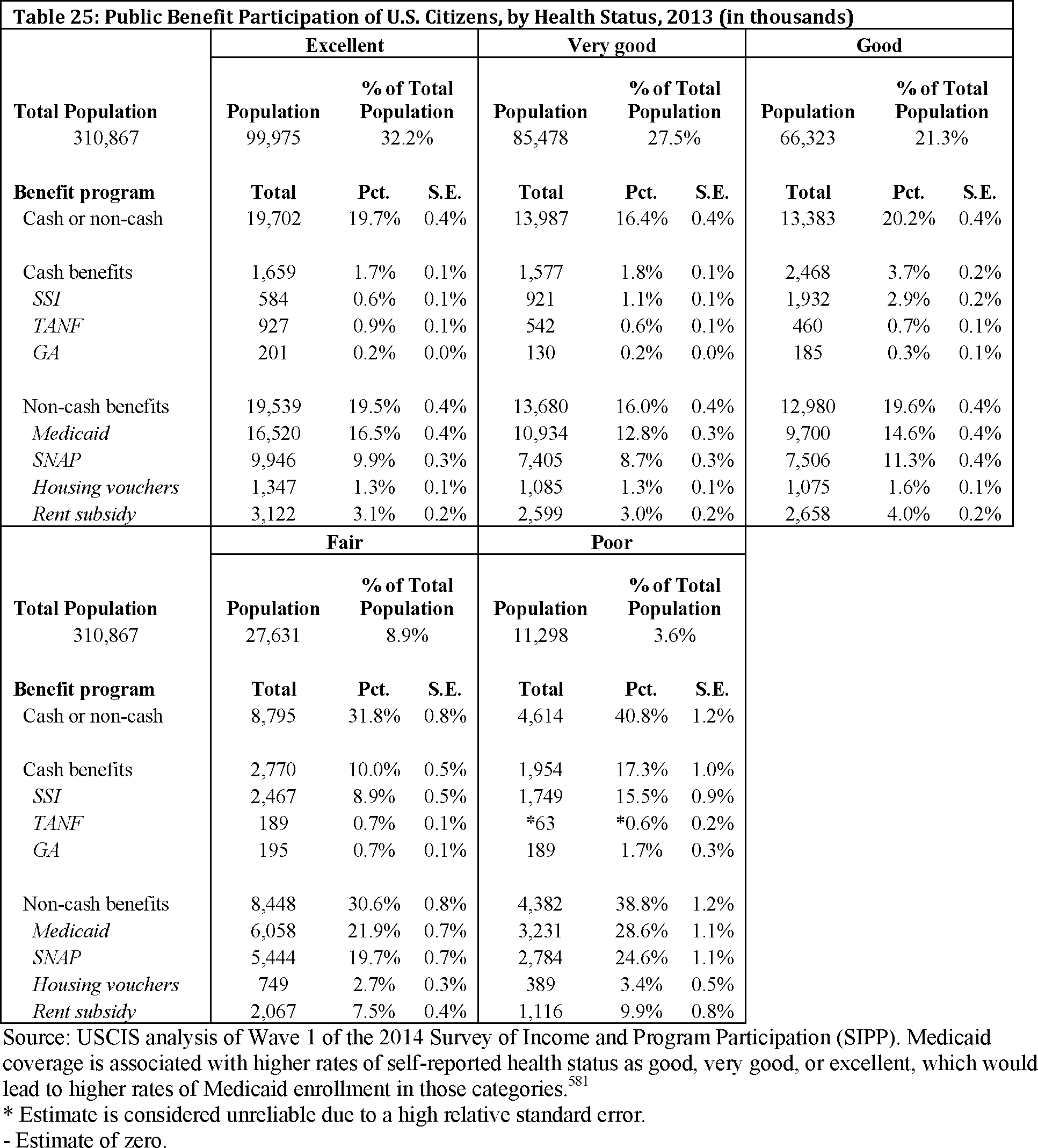

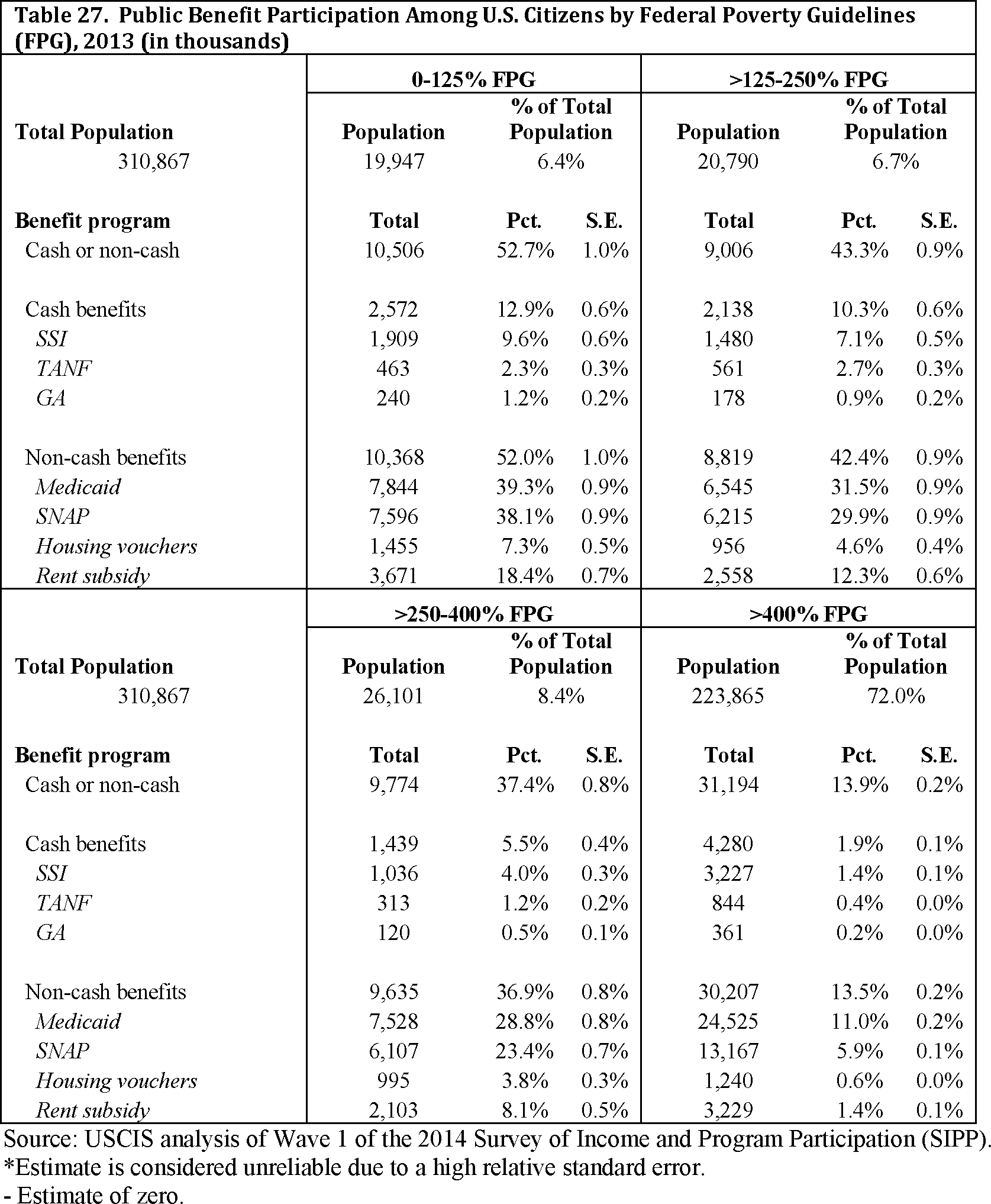

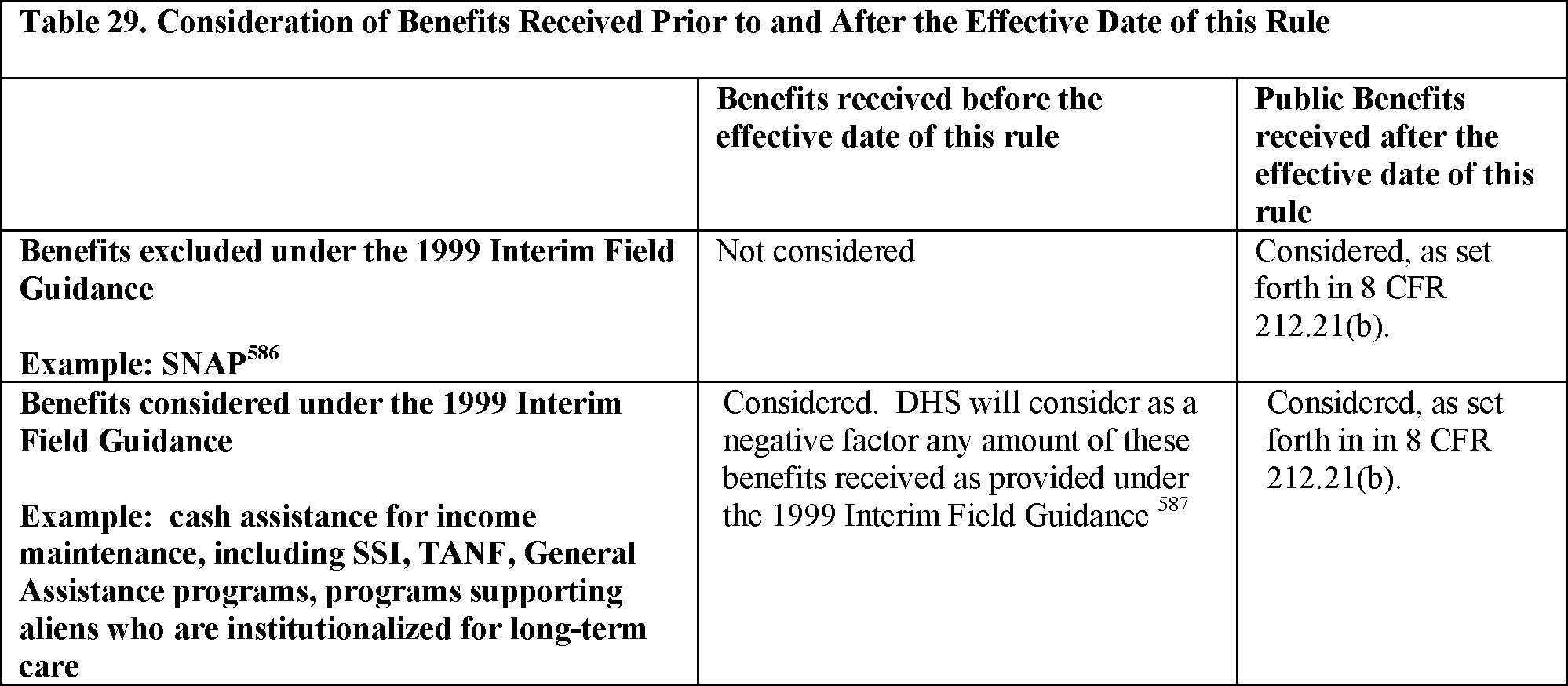

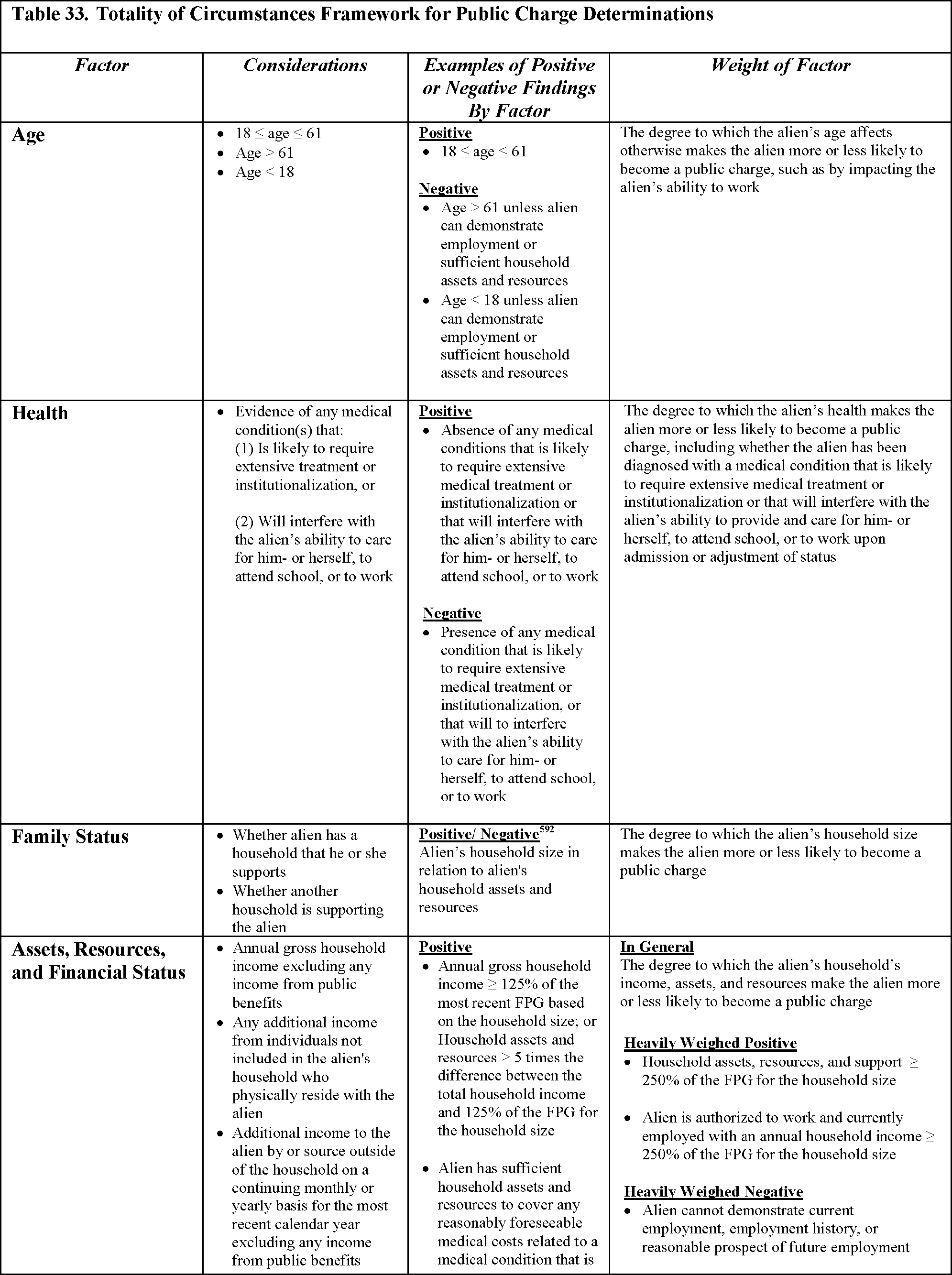

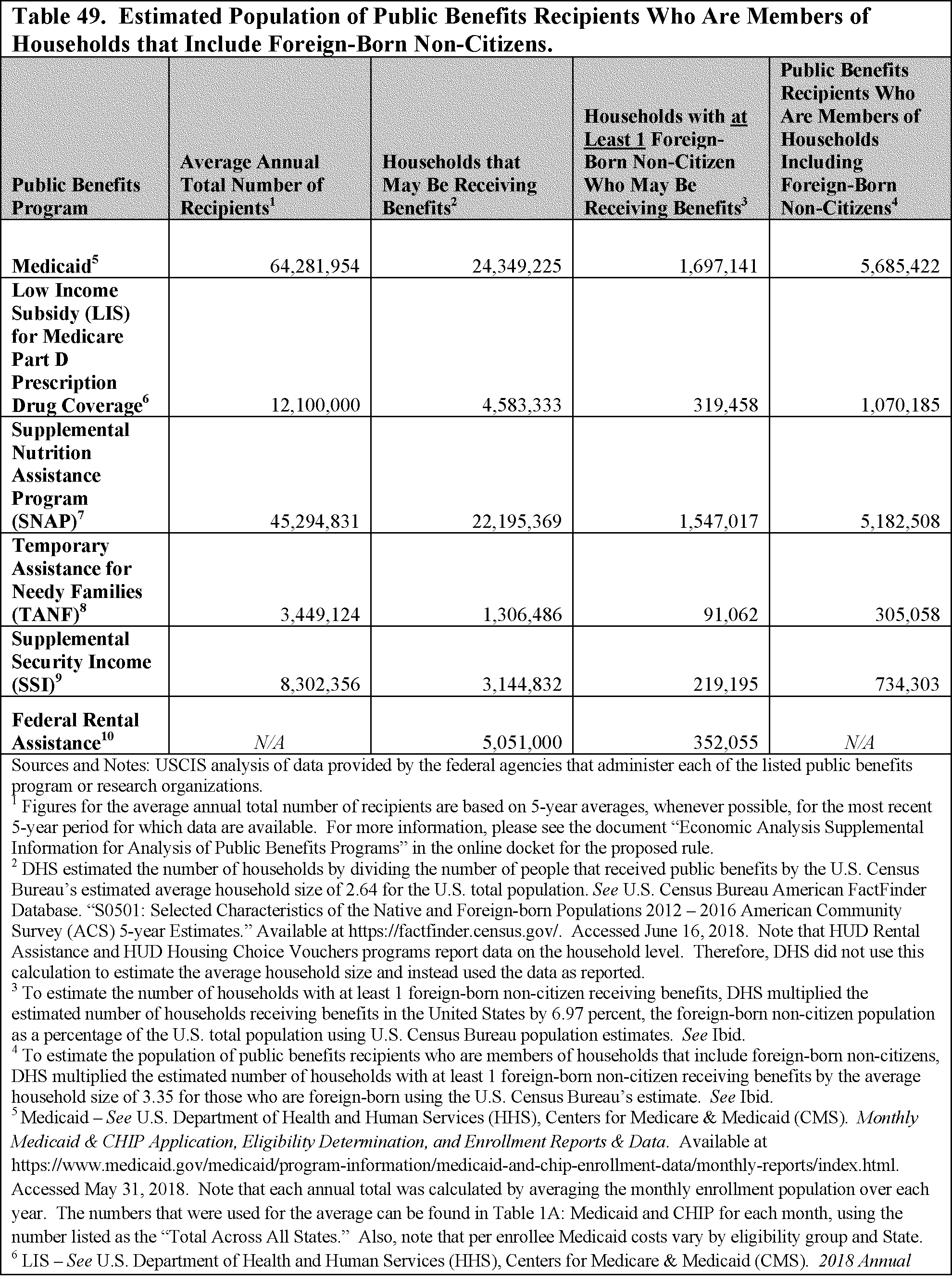

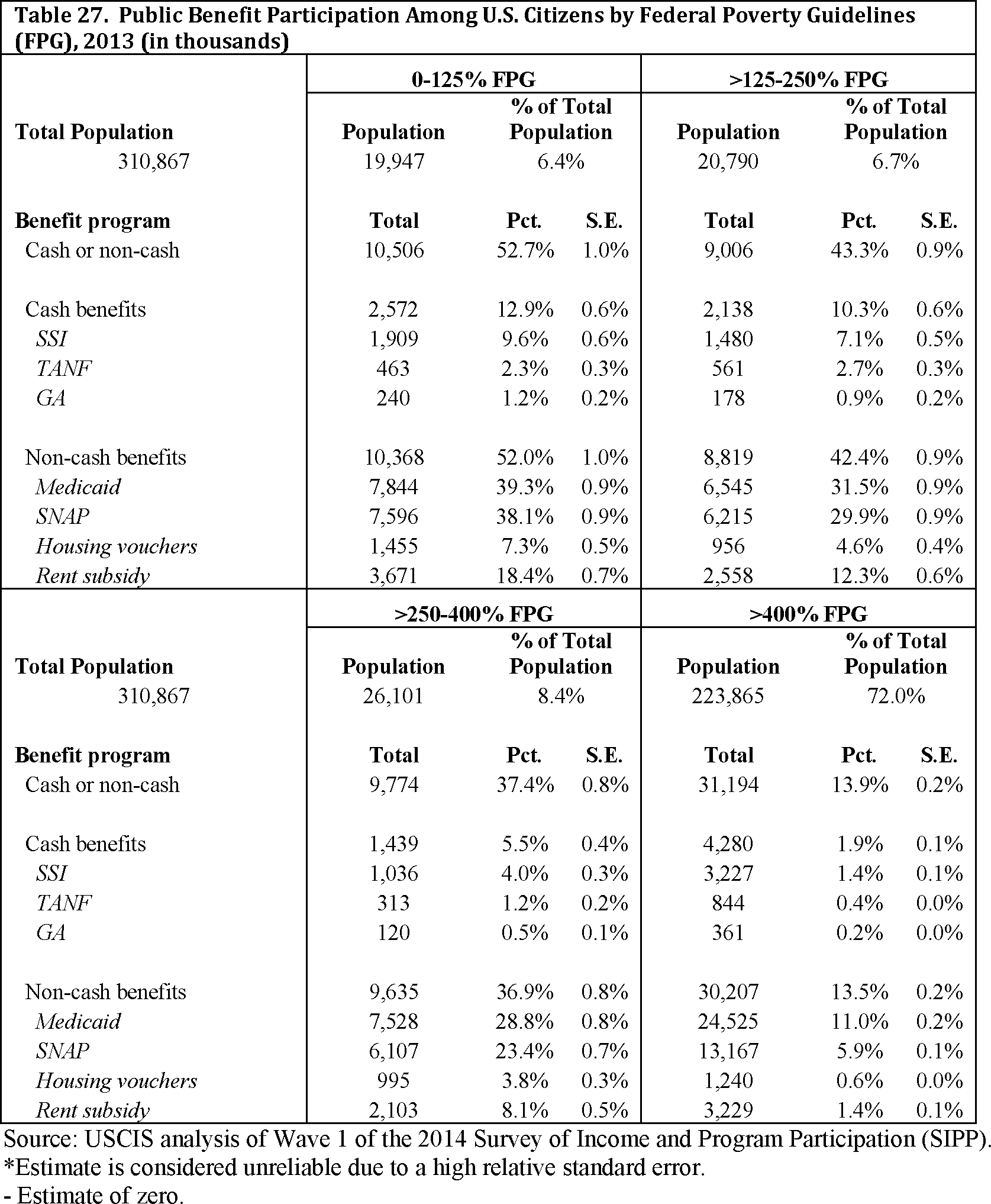

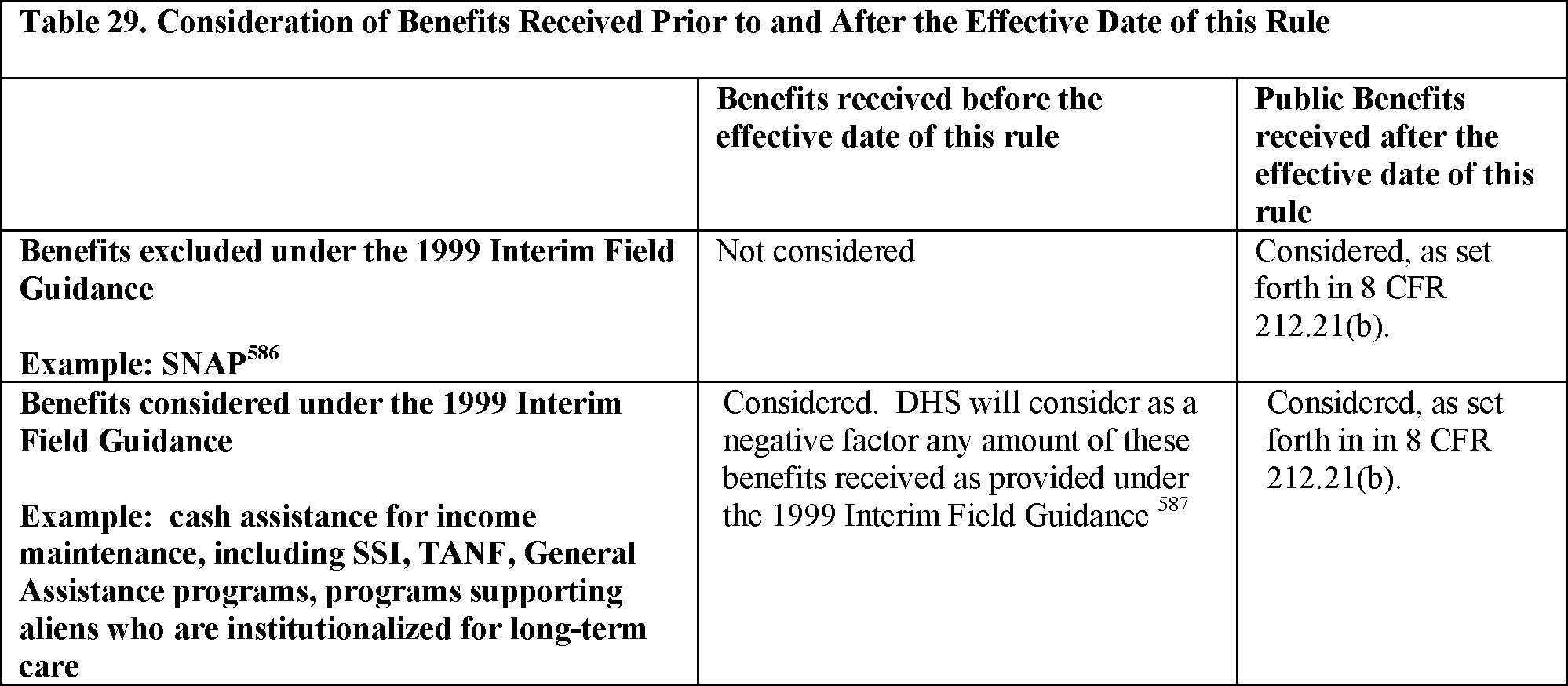

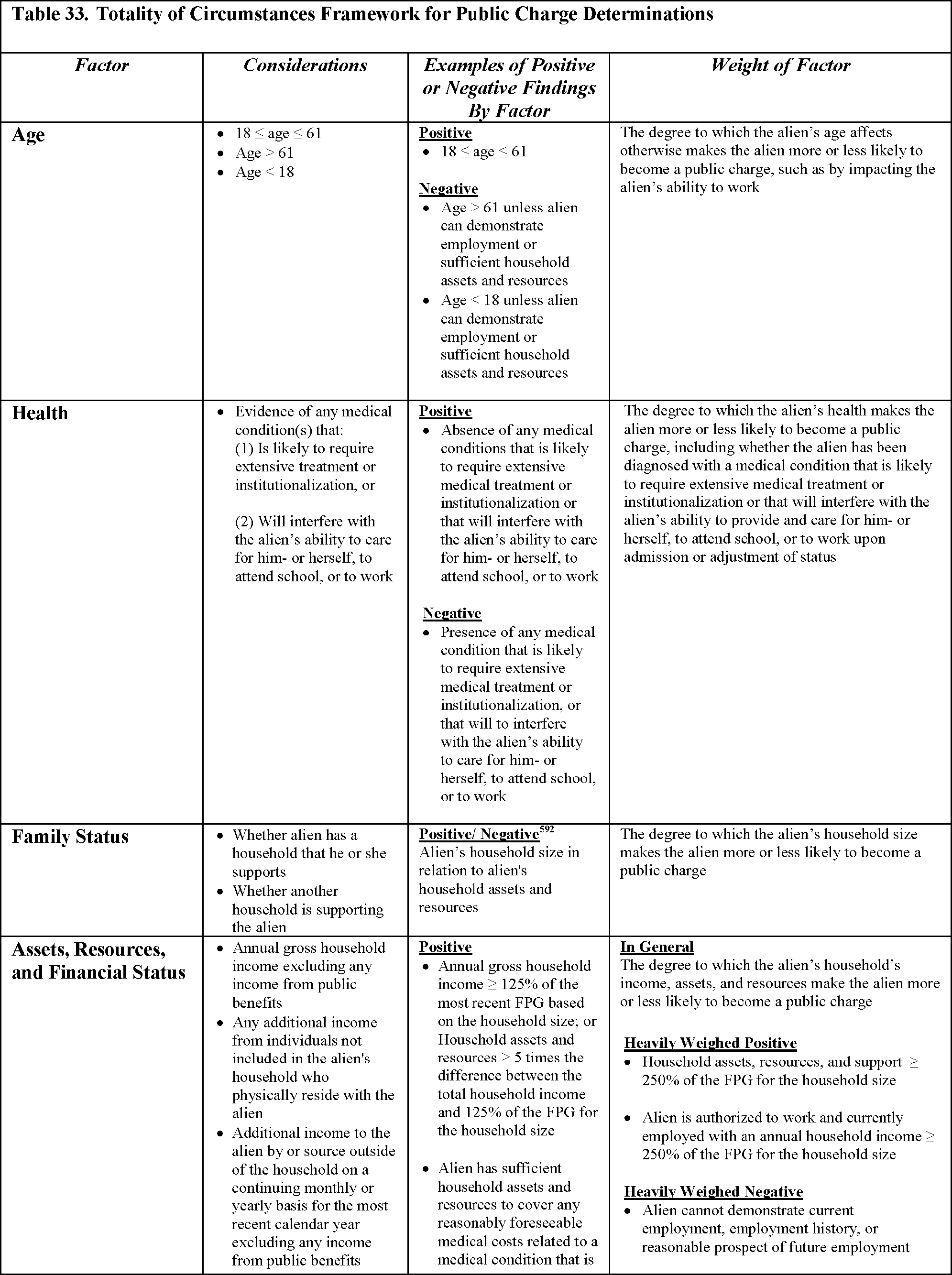

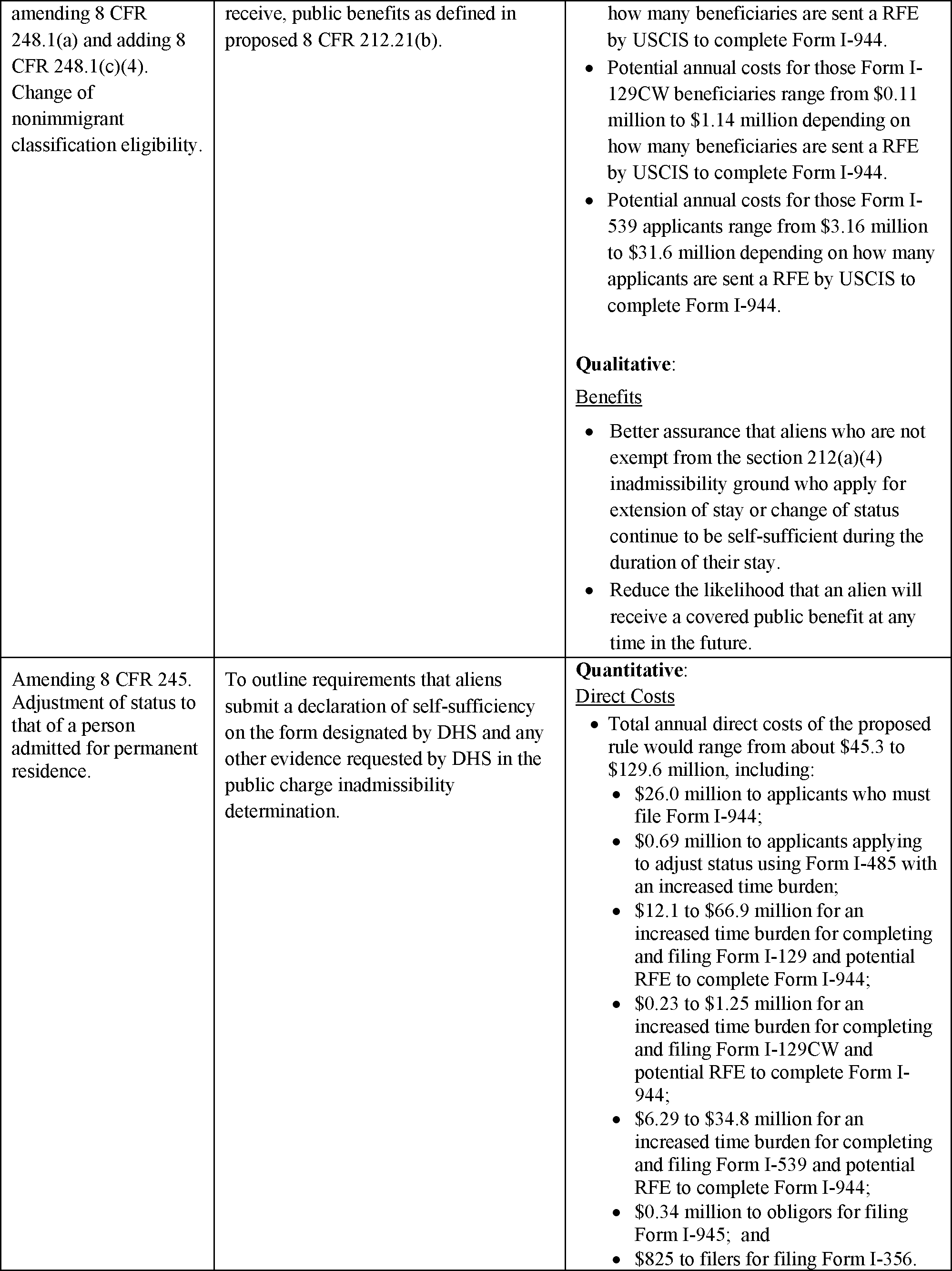

1. Applicants for Admission