• Physical Description of Humpback Whales

• Migration of Humpbacks in the North Pacific Ocean

• Humpback Whale Song in the Breeding Grounds

• Foraging (Feeding) Behaviors

Quick Facts

• Grow up to 50 feet (15.25 m) in length• Up to 70,000 lbs (35 tons)

• Gestation 11.5 months

• Birth 1 calf at a time

• 15-16 feet and 2,000 lbs at birth

• Diet: (Carnivores) Euphausiids, Copepods (krill) and small schooling fish

• Feeding Strategy: Baleen filter feeders

Humpback whale

Megaptera novaeangliae

Kingdom - Animalia

Phylum - Chordata

Class - Mammalia

Order - Cetacea

Suborder - Mysticeti

Family - Balenopteridae

Genus - Megaptera

Species - Novaeangliae

Common Name: Humpbacks are named for the steep arching of the back characteristic when they descend on deep, sounding dives.

Scientific Name: Megaptera is Latin for great, or large winged. This is descriptive of their pectoral flippers (side flippers), which are unusually long. The species name, novaeangliae, is Latin for New Englander given because of the location humpbacks were first described by scientists.

Physical Description of Humpback Whales

Humpback whales are the most commonly sighted baleen whales in the Juneau area. When trying to distinguish humpbacks from other whales, there are a few unique features that can be used. Humpbacks have longer pectoral flippers (side flippers) than any other marine mammal. These flippers are striking in comparison to other whales, measuring roughly 1/3 of their body length.

They also have distinct protuberances on their head and chin. These protrusions, called tubercles, contain a single hair. The purpose of these hairs is unknown, though it is speculated that they are sensory hairs that perform much like whiskers.

Another noteworthy feature of a humpback whale is the 14-22 grooves that run the length of their undersides, from their chin to their navel. These grooves are called ventral pleats, and they allow the throat cavity to expand many times its normal size. This is an important feature in the filter feeding strategy of this baleen whale.

Humpback whales, along with all other baleen whales, have a paired blowhole atop their heads. In contrast, all toothed whales (such as killer whales) have single blowhole.

Humpbacks have an enormous lung capacity which makes it possible for these animals to dive for long periods, often in excess of 20 minutes. These extended dives allow the animals to descend to deep water for foraging (up to 500 feet). When a whale breaks the surface of the water for a breath, it only has a few moments to exchange the air in its lungs, so it must exhale with tremendous force. The force of this exhale vaporizes the seawater that surrounds the blowhole and creates a ‘blow’ at the surface of the water. This vertical pillar of water vapor is usually the first indication that a whale is in the area.

Migration of Humpbacks in the North Pacific Ocean

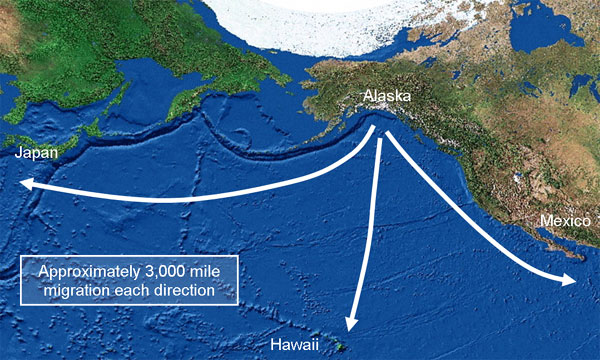

Humpbacks make long, trans-ocean migrations allowing them to spend summers in high latitudes feeding and winters in lower latitudes where the water is warmer and more conducive to birthing and breeding.

In the North Pacific Ocean, humpbacks can be found in waters of British Columbia, Alaska and eastern Russia foraging (feeding) during the summer season and in one of the major breeding areas in the winter months; Hawaii (most common), Central America, Mexico or Asia.

While humpbacks will follow this general seasonal pattern, there are exceptions and described migration patterns are really only general patterns observed. For example, humpbacks are expected to leave Alaska in winter months, though this is not always the case. Humpbacks can be observed in Alaskan waters every month of the year, though only in low numbers from December through March. Because there have been few documented cases of individual humpbacks in the foraging areas all year round, it is likely that the whales unexpectedly present in winter months are usually a combination of “late-departing” and “early-returning” migrating whales.

Researchers have found strong breeding and feeding fidelity, or tendency for animals to return to the same areas year after year. This may be an indication that humpbacks are likely to feed and breed in the same areas as their mothers.

Interestingly, it is still unknown how humpbacks are capable of navigating to breeding and feeding grounds with such high success. It is quite intriguing that a whale in Juneau waters can weave its way out the channels and dead ends of the Inside Passage and make its way to the relatively small chain of Hawaiian Islands, located in the middle of the largest ocean basin on earth. While some theories exist, the exact methods used by humpbacks for navigation remain a mystery.

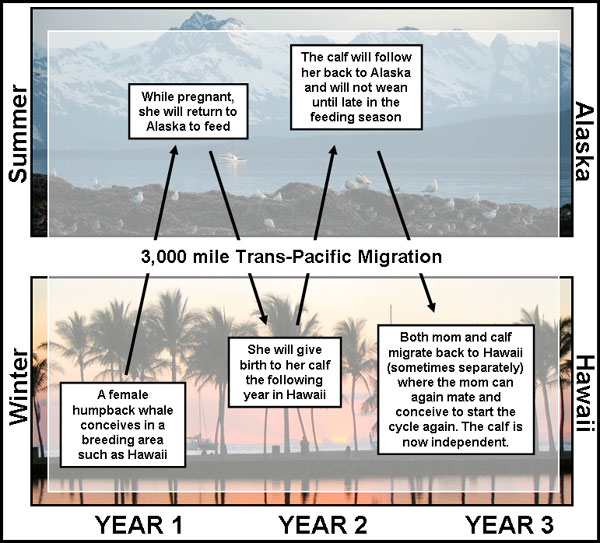

This migration takes humpbacks a minimum of about 30 days in each direction. The figure below follows the migration pattern of a female throughout a pregnancy and time with a dependent calf.

When humpback whales are migrating and in the breeding grounds, there is little to no available food. This is a time when humpbacks survive by metabolizing the food energy in their blubber stores. It is common for whales to return to Alaska from this migration having lost 1/3 of their body weight.

This time is especially taxing on new mothers. A female must nurse her calf immediately, though she herself is fasting. It is estimated that she delivers over 100 gallons of thick, 55% fat milk to her calf every day. Despite this obvious challenge, she will provide food for her calf for a number of months before she can get back to the feeding areas to replenish her blubber stores.

Underwater nursing poses unique challenges, which are overcome in a number of ways. First, nursing occurs in short bursts. Second, the mammary gland is triggered by direct pressure, so the calf can insert a rolled tongue into the mammary gland and trigger the flow of milk. Third, the consistency of the food is think, and much closer to what we would call yogurt, this helps the milk stay together rather than dispersing into the surrounding water.

Humpback Whale Song in the Breeding Grounds

The best known whale vocalization is the humpback song. This is a rather meticulous composition of grunts, moans, squeals and other indescribable sounds. The song is heard primarily in the winter breeding grounds, though has been regularly documented in the feeding areas in the fall and winter months. Whales generate these elaborate songs while suspended underwater. These songs have complex musical organization homologous with music we are familiar with; including repeating themes, phrases and sub-phrases. Curiously, whales throughout the Pacific Ocean sing a remarkably similar version of this song. The song evolves and changes primarily during the breeding season, and all singing whales will adjust and use the most current version. Only male humpbacks have been proven singers, suggesting that this song plays a role in breeding.

For more information about humpback whale song, visit: http://www.whaletrust.org/

Other noises produced by whales include social and feeding related vocalizations. Sounds produced by humpback whales are low in frequency, generally lower than 1.5 kHz. Low frequency sounds, such as these, are conducive for traveling great distances through the water.

Since food is unavailable to humpbacks in the breeding areas, they sustain a focused feeding effort throughout their stay in northern latitudes, where food is abundant. With the exception of traveling and short rest periods, humpbacks in Alaska are feeding virtually all day and night. When the prey source is subsurface, whales will spend only short periods at the surface to breath in between longer (5-8 min) foraging dives. At other times, humpbacks can be seen feeding on surface prey by skimming the surface of the water, or lunging, mouths open to the surface.

Humpback whales are filter feeders, they obtain food by engulfing large amounts of water and prey (small schooling fish, or small crustaceans such as euphausiids and copepods often called krill) and push the water back out of their mouths through baleen plates which act to sieve and retain the prey in the whale’s mouth. Their mouths have some interesting features which make this feeding strategy possible.

- They have an expandable throat space. The ventral pleats can expand to accommodate thousands of gallons of water and prey in a single mouthful.

- Humpbacks have a tongue that is both huge and powerful. It is the tongue that really forces the water out of the throat cavity and through the baleen. Once strained, it is the tongue that licks the fish and krill from the baleen plates so they can be swallowed.

- Their actual throat it relatively small, at largest, this is only about as large around as a basketball. Baleen whales have a digestive system capable of processing only small organisms; the restriction at the throat assures that only small and digestible organisms are swallowed.

- Most importantly, humpback whales have several hundred baleen plates which allow them to separate the food and seawater. They are oriented on the upper jaw in the place of teeth with the fringe positioned towards the inside the mouth. Because the pieces are arranged so closely in the mouth, the roof of a humpbacks mouth looks more like a mat of hair than individual plates of baleen.

Bubble Net Feeding in Southeast Alaska

Occasionally, humpbacks in Southeast Alaska will feed in coordinated groups using bubbles to trap fish at the water’s surface. This behavio r is known as bubble net feeding. Bubble net feeding involves anywhere from 4-20 whales all working together to herd schooling fish into dense schools in order to maximize the feeding productivity of the group.

While many other whales and other animals use bubbles to assist in prey capture, the specific methods used in this complex feeding strategy are unique to whales in Southeast Alaska and are seen only in certain areas and seasons. To summarize the bubble net technique; a group of humpbacks will dive down to herring schools where one whale (the bubble-blower) will release a ring of bubbles from its blowhole as it spiral beneath the prey. As this air rises to the surface, it creates a curtain of bubbles that acts as a physical barrier to frighten and retain the school of herring. Simultaneously, another whale in the group will produce resonating vocalizations, which also act to frighten the prey and trigger them to school up in tight balls within the bubble net. The whales then orient below the schooled fish and lunge, mouths open, to the surface through the center of the bubble ring, or bubble net. This motion drives the fish to the surface, where they are trapped from all sides (the surface of the water above, the bubble curtain on the sides and the open mouths of whales below). The whales will break the surface of the water in unison with mouths wide open, and then close their mouths while roll at the surface as they force the water from their throat cavity out through their baleen plates; the sieving process which allows them to swallow their catch without having to swallow excess saltwater.

Perhaps the most amazing aspects of this feeding behavior are in the precision and organization of the group. The whales in a bubble netting group will surface in the same relative orientation with each successful bubble net, in some ways this behavior can be viewed as a highly organized dance. Further, it is fascinating that these animals are capable of coordinating this behavior while partitioning tasks to increase the overall efficiency. This behavior signifies complex social interactions within humpback whale populations, which are poorly understood and documented.

Research groups, such as Alaska Whale Foundation, strive to understand the various roles of the whales involved in these groups, the full purpose of the vocalizations and bubbles, and to document the individual whales that partake in order to shed more light on this complex and fascinating display of animal cooperation.

Other behaviors seen in humpback whales can include acrobatic displays. Humpbacks have a reputation for their elaborate surface activities including; breaching, spy hopping, pectoral flipper slapping and tail lobbing. These behaviors are often sporadic and difficult to interpret. While the purpose of these behaviors is largely unknown, some speculate they could be used for; social interactions, communication, looking above the surface of the water, sloughing barnacles and dead skin fragments or as play behaviors.