Louis M. Staudt, M.D., Ph.D., and members of

his NCI laboratory

In a development that is literally lifesaving, Dr. Staudt, who has been on the staff of NCI for nearly 20 years, has successfully used genomic technology to reliably distinguish Burkitt's lymphoma from Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas (DLBCL).

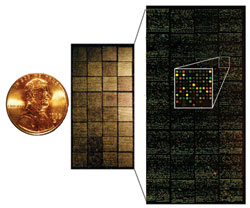

With DNA microarrays, researchers are

beginning to unravel the complexities and

highlight the unique genetic features of the

30-plus forms of lymphoma

The Lymphoma/Leukemia Molecular Profiling Project (LLMPP) is a network of 11 clinical groups that maintain biospecimens and clinical data from hundreds of patients with this cancer of the lymphatic system. An international consortium of investigators, including NCI-funded investigators and researchers around the world, the LLMPP is classifying lymphoma by distinct molecular characteristics and is then using that information to more accurately guide diagnosis and to target treatment.

Louis M. Staudt, M.D., Ph.D., studies lymphoma, a cancer of the lymphatic system that affects 23,000 patients yearly and causes 10,000 deaths Treatment can be dfficult, because this cancer has many subtypes, which require different treatment options. For example, Burkitt's lymphoma and diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) are difficult to diagnose because the two cancers appear very similar under a microscope. However, the two are genetically distinct, and thus require very different treatments.

And the stakes couldn't be higher. "If Burkitt's patients are treated with intensive therapy, there is roughly an 80 percent survival rate," says Dr. Staudt, deputy chief of the Metabolism Branch and head of the Molecular Biology of Lymphoid Malignancies Section in NCI's Center for Cancer Research. "However, if they are misdiagnosed and treated with the lower intensity chemotherapy recommended for DLBCL, the survival rate is 20 percent or even less."

In a development that is literally life-saving, Dr. Staudt, who has been on the staff of NCI for nearly 20 years, has successfully used genomic technology to reliably distinguish Burkitt's lymphoma from DLBCL. Dr. Staudt demonstrated that DNA microarrays, a technology rooted in the Human Genome Project, can accurately distinguish Burkitt's lymphoma from DLBCL, thereby optimizing the treatment choice for each patient. "The current goal with the improved diagnostics technology is to make it uniform, reproducible, and available as a cost-effective test," notes Dr. Staudt.

In collaboration with a private sector company, researchers are now enrolling 2,000 to 4,000 patients for a large study of a new test designed to distinguish between all types of lymphomas and other, benign conditions.

Even as work continues on better diagnostics, Dr. Staudt points out that improved lymphoma treatments are also being discovered. Dr. Wyndham Wilson, a clinician at the NIH Clinical Center, has developed a novel, less toxic form of chemotherapy to treat Burkitt's lymphoma, called dose-adjusted EPOCH-R. In this treatment, the dosage of chemotherapeutic drugs is increased with every cycle until a maximum tolerated dosage is reached. "It's an empirical way of adjusting the dosage to fit each patient, which avoids both under treatment and over treatment," says Dr. Staudt. "This approach adjusts for differences in metabolism, age and genetics that can influence a patient's response to drugs."