|

||

|

||

|

|

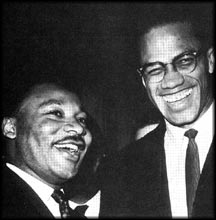

Black Separatism or the Beloved Community? Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.Lesson Plan Two of the Curriculum Unit: Competing Voices of the Civil Rights MovementIntroduction"You don't integrate with a sinking ship." This was Malcolm X's curt explanation of why he did not favor integration of blacks with whites in the United States. As the chief spokesman of the Nation of Islam, a Black Muslim organization led by Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X argued that America was too racist in its institutions and people to offer hope to blacks. The solution proposed by the Nation of Islam was a separate nation for blacks to develop themselves apart from what they considered to be a corrupt white nation destined for divine destruction.In contrast with Malcolm X's black separatism, Martin Luther King, Jr. offered what he considered "the more excellent way of love and nonviolent protest" as a means of building an integrated community of blacks and whites in America. He rejected what he called "the hatred and despair of the black nationalist," believing that the fate of black Americans was "tied up with America's destiny." Despite the enslavement and segregation of blacks throughout American history, King had faith that "the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God" could reform white America through the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement. This lesson will contrast the respective aims and means of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. to evaluate the possibilities for black American progress in the 1960s. Guiding Questions

Learning ObjectivesAfter completing this lesson, students should be able to:

Background Information for the TeacherBorn Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm X (1925-65) was the son of a West Indian mother and black Baptist preacher. His father was a local organizer for Marcus Garvey's United Negro Improvement Association, which promoted black separatism and pan-Africanism. After moving to Lansing, Michigan, Malcolm suffered the death of his father (under suspicious circumstances) and several years later saw his mother committed to a mental institution. A top student in elementary school (who was elected the seventh-grade class president), Malcolm told his English teacher he wanted to be a lawyer; he was told, "That's no realistic goal for a Nigger," and he soon asked to go live with his half-sister Ella in Boston. He took a job as a shoe-shine boy; later became a street hustler in New York; and eventually was imprisoned for burglary before his twenty-first birthday. Malcolm read voraciously in prison and was introduced to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam (NOI) by his siblings and inmates. Paroled in August 1952, he went to live in Detroit with his eldest brother Wilfred.After meeting Elijah Muhammad, he began recruiting converts for the local NOI temple and officially adopted "X" for his surname, which represented his lost African family name. He quickly rose through the ranks of NOI temple ministers. Malcolm married Betty X (née Sanders) in January 1958, who bore him four daughters while he was alive and twins after his death. In 1959, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam gained national prominence with the airing of "The Hate That Hate Produced," a documentary by Mike Wallace and Louis Lomax, and subsequent articles in U.S. News & World Report and Time magazine. By 1960, Malcolm X had started or helped start over a hundred temples with thousands of converts; founded the NOI's newspaper Muhammad Speaks; wrote a syndicated column entitled "God's Angry Men" for major black newspapers; and became Elijah Muhammad's chief spokesman. Malcolm X's popularity soon distanced him from rival ministers at the Chicago headquarters. In addition, Elijah Muhammad's bad health and rumors of his infidelity with NOI secretaries led to uncertainty about the future leadership of the Nation. After John F. Kennedy's assassination in November 22, 1963, Elijah Muhammad directed his ministers not to comment on the death of a president popular among black Americans. But after giving a speech entitled "God's Judgment of White America" on December 4, 1963, Malcolm X called the assassination a case of "the chickens coming home to roost." Elijah Muhammad promptly silenced Malcolm X for ninety days. Convinced that jealous rivals were undermining his reputation with the ailing Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam in March 1964 and announced the formation of the Muslim Mosque, Inc. Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam at the climax of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s fame as leader of the Civil Rights Movement. During 1963 and 1964, King was chosen Time magazine's "Man of the Year"; drew national attention to "Bull" Connor's barbaric law enforcement; penned his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail"; delivered his most famous speech ("I Have a Dream") at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom; saw passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act; and received the Nobel Peace Prize. To justify an alternative message for black liberation in America, Malcolm X painted a stark contrast between his philosophy and that of the most popular civil rights spokesman of his day. After a pilgrimage to Mecca in April 1964, where he became a Sunni Muslim (and referred to the NOI as a "pseudo-religious philosophy"), he returned to America as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz and formed the Organization of Afro-American Unity. No longer asserting that whites were "devils," but still skeptical of American institutions to secure the civil rights of black Americans, Malcolm argued that the civil rights movement needed to be taken to a more receptive international forum such as the United Nations and World Court. Denounced by his protégé Louis X (Farrakhan) in Muhammad Speaks as "worthy of death," and suspecting he was poisoned during a tour of Africa, Malcolm X saw his death as imminent. On February 14, 1965, his home was firebombed, and on February 21 Malcolm X was shot to death as he began a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. For Malcolm X, discussing his legacy is complicated by his departure from the Nation of Islam in March 1964, which was followed by a year of self-examination and public exploration of alternative approaches to helping black Americans secure their rights. Although he became famous between 1959 and 1963 as the lead spokesman for the Nation of Islam, his controversial exit from the Black Muslim organization and his eventual assassination in February 1965 make it difficult to give a definitive account of what he actually believed. This lesson will focus on the ideas and recommendations of Malcolm X that produced his greatest fame and notoriety as the public face of the Nation of Islam. (Students can explore some of the changes that his thinking underwent in the last year of his life in the "Extending the Lesson" section of this lesson.) During his seventeen-year association with the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X did not consider politics a legitimate activity for black Americans. He believed that the United States governments (both state and federal) represented the interests of whites exclusively, which made political participation by black Americans a waste of time at best, and complicity in their own oppression at worst. The "so-called Negro," as Elijah Muhammad called black Americans, needed to stay as far away as possible from the white institutions of power. These institutions included not only political parties, offices, and elections but also schools, workplaces, and social venues. According to the Nation of Islam's religious dogma, the one true God, Allah, destined whites for imminent annihilation. Therefore, the less integrated blacks were with white society, the better. Malcolm X believed that the only way to be free from the cultural hegemony of white America was through the reeducation of black Americans. Central to that reeducation was the rejection of the traditional Christianity of black America. Malcolm X read current events in light of Nation of Islam eschatology. With "the race problem" in the U.S. as the problem in modern-day America, Malcolm X believed only God's "Messenger," Elijah Muhammad, knew the true nature of the problem and how it could be solved. Unlike Martin Luther King, Jr., who appealed to the conscience and justice of white America, Malcolm X highlighted the longstanding and manifest injustices of white America to persuade black Americans to seek a separate black state large enough to include all 22 million black Americans then residing in the United States. Self-understanding for black Americans could only come through their becoming a nation unto themselves and form their own schools, shops, and businesses. For an introduction to Martin Luther King, Jr.'s involvement with the Civil Rights Movement, see Sections I and IV of Lesson #1 of "Competing Voices of the Civil Rights Movement" unit, entitled "Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nonviolent Resistance: To Obey or Not to Obey?" Preparing to Teach this LessonThis lesson makes use of sound recordings, written primary source documents, and worksheets, available both online and in the Text Document that accompanies this lesson. Students can read and analyze source materials entirely online, or do some of the work online and some in class from printed copies.Read over the lesson. Bookmark the websites that you will use. If students will be working from printed copies in class, download the documents from the Text Document and duplicate as many copies as you will need. If students need practice in analyzing primary source documents, excellent resource materials are available at the EDSITEment-reviewed Learning Page of the Library of Congress. Helpful Document Analysis Worksheets may be found at the site of the National Archives. Note: Discussion of the Civil Rights Movement can elicit strong responses from individuals, even today. Teachers should be aware of this and closely monitor class discussion, particularly when addressing the derogatory language used to describe different groups of people during this time period. Suggested ActivityActivity: A Journalist's Report: The Better Vision for Black AmericansThis activity is built around the following sequence of tasks: 1. Students gain an understanding of the mission of Civil Rights Movement and the context in which it occurs (a) General overview of the civil right struggle of the 1960s2. Students hear the rhetorical power of Malcolm X and analyze primary sources blockquote>(a) Audio recording of Malcolm X, "Message to the Grassroots" (November 10, 1963) 3. Students hear the rhetorical power of Martin Luther King, Jr., and analyze primary sources 4. Students write reports in which they evaluate the two activists and judge which leader's goals could best secure a better life for black Americans. In the activity for this lesson, students will be playing the part of a reporter from a large city newspaper in the 1960s. This reporter has seen first-hand the inner-city problems and racial conflict that are tearing at the seams of society. He knows that the black community is hearing two persuasive voices: those of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., whose approaches to solving the difficulties are poles apart. His editorial board assigns him the task of writing a column on the two leaders, briefly assessing their strengths and weaknesses, but also judging whose approach better solves the problems facing the black community. Before he writes this column, however, he travels to hear the speeches of the two men, and takes an up-close look at key speeches and writings. In order for students to know why they are listening and doing research, they should be told at the beginning that the goal of their stint at journalistic writing is a column for the newspaper. They can then proceed with the assignment with this final objective in mind. Let them know that the final report will be graded. If an additional prize is to be offered for the best report or reports, announce this before the project begins. Give students the option of either working individually or working in pairs as a journalistic team. Start this activity with a homework assignment. A day or two before the lesson begins, have students gain historical context for this assignment by accessing two EDSITEment-reviewed websites or by reading printed copies of the same information located in the Text Document on pages 1-3, distributed to students in advance. 1. (a) For an overview of the civil rights struggle of the 1960s, see paragraphs one, two, and five at the following site, linked from the EDSITEment-reviewed "American Studies at the University of Virginia". 1. (b) Tell students to pay particular attention to specific examples of racial discrimination and segregation laws found in the following EDSITEment-reviewed website from the National Park Service: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/travel/civilrights/intro1.htm. (Students need to scroll down to the bottom of the page and click on "The Need for Change.") Have students take notes on these sites for later use in their newspaper articles. 2. (a) On the first full period devoted to this lesson, begin class with an introduction to Malcolm X's provocative rhetoric by having students listen to 3-5 minutes of his November 10, 1963 speech, "Message to the Grassroots", linked from the EDSITEment-reviewed "American Studies at the University of Virginia". Given the length of the audio clip, you may want to suggest that each student listen to a different 3-5 minute segment of the speech to give a more expansive coverage of Malcolm X's riveting oratory. 2. (b) Next, have students read Louis Lomax's interview of Malcolm X (November 1963) and answer the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on pages 9-10 of the Text Document. A link to the text "A Summing Up: Louis Lomax Interviews Malcolm X" can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "Teaching American History". For a shorter version of the interview that can be printed out and distributed to the students, see the excerpted version on pages 4-8 of the Text Document.

3. (a) Begin day two by introducing students to Martin Luther King, Jr.'s stirring rhetoric by having them listen to a brief excerpt from his "I Have a Dream" speech. Go to the EDSITEment-reviewed site "Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project: Popular Requests" and click the Quicktime or Realmedia link for a three-minute, audio excerpt from "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom." 3. (b) Then, spend part of the class having students read Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "The Power of Nonviolence" (June 4, 1957) and answering the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 17 of the Text Document. A link to the text of "The Power of Nonviolence" can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "Teaching American History". The speech is also included in the Text Document on pages 14-16, and can be printed out for student use.

A link to the full text of King's "Letter from Birmingham Jail" can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project":. For purposes of this lesson, use the excerpts from the essay, located on pages 18-22 of the Text Document.

4. After students have gained an understanding of the key ideas of the two leaders, they are ready, as reporters, to assume their final, culminating task of writing their columns for the newspaper. Devote most of the class time to the writing assignment. The article should include the following points, using the Text Document guidelines on page 25, which students should have in hand for reference as they write:

AssessmentAssessment #1: Grade the final report.Assessment #2: Evaluate, Reflect, DialogueInstruct students to give a one- or two-paragraph answer to any or all of the following questions, which are available in worksheet form on pages 26-27 of the Text Document:

Extending the Lesson1. A Different Malcolm X: From Nation of Islam Spokesman to Independent Political ActivistWhile a member of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X was apolitical. This was due to Elijah Muhammad's strictures against Black Muslims participating in a political system he believed was rigged against blacks. Malcolm X was chiefly a religious spokesman who exhorted black Americans to separate from what he viewed as white American institutions. His message to white Americans was to repair the damage they had done to black Americans (for example, by giving them a separate state and money for 25 years to get started), or else God's judgment would fall on them for domestic oppression and international imperialism and colonialism.After Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam in March 1964, he felt free to offer political solutions to the problems that afflicted black Americans. He was still dubious of the American political system, but advised black Americans to (1) engage in smarter political voting and organization (for example, no longer voting for black leaders he viewed as shills for white interests) and (2) fight for civil rights at the international level, where he thought the non-white nations of the world would side with the oppressed black American minority and pressure the United States (through the United Nations and World Court) to protect their rights. A month after leaving the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X gave a speech entitled "The Ballot or the Bullet." This speech will help students understand how his thinking about America and black progress was evolving. In particular, it will explore how his goal and methods changed after he left the Nation of Islam. Have students read the "The Ballot or the Bullet" (April 3, 1964) and answer the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on pages 7-8 of the corresponding Text Document. A link to the text "The Ballot or the Bullet" can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "Teaching American History". For purposes of this lesson, use the excerpts from the speech, located on pages 1-6 of the Text Document.

2. King Confronts the Black Power MovementAfter Malcolm X's violent death in February 1965, and amidst urban riots the following year, increasing numbers of black youth rejected Martin Luther King, Jr.'s nonviolent methods and sought a more militant approach to combating white supremacy in America. The cry of "Black Power," instead of "We Shall Overcome" and "Freedom Now," became the slogan of a new faction of the Civil Rights Movement. In response to Black Power advocates, King wrote an article for Ebony magazine that directly addressed the claims of this new movement and explained why he believed nonviolent protest remained the most prudent means of advancing the cause of black Americans.Have students read King's October 1966 essay, "Nonviolence: The Only Road to Freedom," and answer the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on pages 14-15 of the Text Document. A link to the "Nonviolence" text can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "Teaching American History". A shorter excerpt from the article is also included in the Text Document on pages 9-13, and can be printed out for student use.

Related EDSITEment Lesson Plans

Previous Lesson PlanReturn to the Curriculum Unit Overview: Competing Voices of the Civil Rights MovementSelected EDSITEment Websites

Standards Alignment View your state’s standards |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||

| EDSITEment contains a variety of links to other websites and references to resources available through government, nonprofit, and commercial entities. These links and references are provided solely for informational purposes and the convenience of the user. Their inclusion does not constitute an endorsement. For more information, please click the Disclaimer icon. | ||

| Disclaimer | Conditions of Use | Privacy Policy Search

| Site

Map | Contact

Us | ||