|

|

Consequences of the Sedition Act

Guiding Question

- What were some applications and consequences of the Sedition Act?

Learning Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to:

- Discuss the consequences of the Sedition Act.

- Illustrate the difficulty of balancing security needs and personal freedom

using an example from John Adams's presidency.

In 1798, Jefferson predicted the consequences of the passage of the Sedition

(and Alien) Act in one of the excerpts reviewed above:

If the Alien and Sedition Acts should stand, these conclusions would flow

from them: that the General Government may place any act they think proper

on the list of crimes, and punish it themselves whether enumerated or not

enumerated by the Constitution as cognizable by them: that they may transfer

its cognizance to the President, or any other person, who may himself be the

accuser, counsel, judge and jury, whose suspicion may be the evidence, his

order the sentence, his officer the executioner, and his breast the sole record

of the transaction: that a very numerous and valuable description of the inhabitants

of these states being, by this precedent, reduced, as outlaws, to the absolute

dominion of one man, and the barrier of the Constitution thus swept away from

us all, no rampart now remains against the passions and the powers of a majority

in Congress to protect from a like exportation, or other more grievous punishment,

the minority of the same body, the legislatures, judges, governors, and counselors

of the States, nor their other peaceable inhabitants, who may venture to reclaim

the constitutional rights and liberties of the States and people, or who for

other causes, good or bad, may be obnoxious to the views, or marked by the

suspicions of the President, or be thought dangerous to his or their election,

or other interests, public or personal: that the friendless alien has indeed

been selected as the safest subject of a first experiment; but the citizen

will soon follow, or rather, has already followed, for already has a Sedition

Act marked him as its prey: that these and successive acts of the same character,

unless arrested at the threshold, necessarily drive these States into revolution

and blood, and will furnish new calumnies against republican government, and

new pretexts for those who wish it to be believed that man cannot be governed

but by a rod of iron.

In this lesson, students will look at documents reflecting some of the consequences

of the Sedition Act. How close was Jefferson's prediction?

1. Supporters of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison believed the Sedition

Act was designed to repress political opposition. The way the act was applied

supports that contention. In all, 25 people were prosecuted under the Sedition

Act. Eventually, 10 were convicted—all were newspaper editors who supported Thomas

Jefferson, a rival of President John Adams. According to the seventh edition

of The Encyclopedia of American History (Morris and Morris, Harper Collins,

1996):

Several of the leading Republican publicists were European refugees. The

threat of war with France sharpened hostility to aliens and gave Federalists

an opportunity to impose severe restrictions….

25 June (1798) The Alien Act authorized the president to order out of the

U.S. all aliens regarded as dangerous to the public peace and safety, or suspected

of "treasonable or secret" inclinations. It expired in 1800….

14 July. Sedition Act made it a high misdemeanor, punishable by fine and imprisonment,

for citizens or aliens to enter into unlawful combinations opposing execution

of the national laws; to prevent a federal officer from performing his duties;

and to aid or attempt "any insurrection, riot, unlawful assembly, or combination."

A fine of not more than $2,000 and imprisonment not exceeding 2 years were

provided for persons convicted of publishing "any false, scandalous and malicious

writing" bringing into disrepute the U.S. government, Congress, or the president;

in force until 3 March 1801.

The Sedition Act was aimed at repressing political opposition….

Republicans attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts as unnecessary, despotic,

and unconstitutional.

Matthew Lyon, the member of the House involved in the fracas described in

Lesson One,

was the first person convicted under the Sedition Act. His crime? Declaring

that President Adams acted more like King John and should be sent "to a mad

house." In court, Lyon would have had to defend himself by proving his remarks

about President Adams to be true and therefore not libelous, false, and so damaging

to President Adams that Lyons deserved punishment. Would it have been possible

for him to do so? Do students consider Lyon's remarks to have been libelous? Were these

trials partisan? Through EDSITEment resources, students

can access a variety of documents about the trials and their aftermath.

2.

How was the Sedition Act used to prosecute speech? Below are four options to

choose from for your class:

What indications of partisanship, if any, are there in the materials the class reviewed? What indications of security concerns, if any, are there? What did students notice about the manner in which any of the trials was conducted?

3. When Jefferson became president, he pardoned everyone convicted under the Sedition Act. However, Congress apparently felt the need to apologize for its abuse of power for the next 50 years. Students can find examples using the EDSITEment-reviewed website American Memory. The act still called for Congressional action to compensate the victims (posthumously) in the 1832 Bill to refund a fine imposed on the late Mathew Lyon, under the Sedition Law and the 1850 Bill to refund the fine imposed on the late Dr. Thomas Cooper, under the Sedition Law.

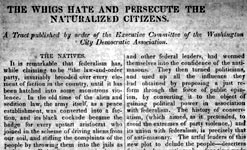

4. The Alien and Sedition Acts were political poison for those who had endorsed them. Federalist support for the acts is often cited as a factor in the victory of Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans against John Adams in the 1800 election. Even in 1828, one could still campaign against someone by saying he was supported by someone who supported the Sedition Act. Share with the class the opening lines of the broadside Jackson triumphant in the great city of Philadelphia on the EDSITEment resource American Memory. Even in 1844, the Alien and Sedition Acts were still worth mentioning in an anti-Whig party tract, The Whigs hate and persecute the naturalized citizens, also available on American Memory.

Assessment

Lead students in a discussion of what they learned through this lesson. They should be able to respond effectively to the following questions:

- What sorts of "crimes" were prosecuted under the Sedition Act?

- What was the political fallout from the Sedition Act?

Our modern understanding of the First Amendment is based on a series of Supreme Court decisions. Though there is no specific rule to use in determining what speech is not protected, there are some general standards. "Writing for the Court in Schenck, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes asked whether 'the words create a clear and present danger that they will bring about substantive evils Congress has a right to prevent?'" (from the Clear and Present Danger Exhibit on Famous Trials, a link from the EDSITEment-reviewed website Internet Public Library).

The Famous Trials website is an excellent starting place for helping students to realize the difficulty of determining the meaning as well as the appropriate applications of the First Amendment. The opinions provided for the four cases all deal in one way or another with the "clear and present danger" rule set down by Holmes in Schenck. The last, Gitlow, addresses an issue raised earlier in the unit—i.e. the application of the First Amendment to the states.

Have the students discuss Holmes' criteria: Who decides whether a danger is "clear and present." and what do the words "clear" and "present" mean?

Extending the Lesson

- Read the World War I U.S. Sedition Act and U.S. Espionage Act on the EDSITEment resource WWI Document Archive. Compare the documents to the Alien and Sedition Acts, and research some of their applications, as demonstrated in the Clear and Present Danger Exhibit on Famous Trials, a link from the EDSITEment-reviewed website Internet Public Library, which includes transcripts of the opinions in four World War I prosecutions under the 20th-century version of the Sedition Act. Justice Holmes wrote opinions in all four of these cases; however, his thinking on the subject of free speech changed over time. Holmes's evolving thought serves to illustrate the difficulty the justices faced in deciding what speech is protected by the First Amendment and when restrictions should be applied. Ask students to read carefully the four opinions written by Holmes on this topic, trace the changes over time, and seek explanations for the developments in his thinking. Conclude with a discussion of whether Holmes's final word on this subject left a clear guideline for courts to follow.

- Interested students can research the connection between the Jeffersonian Claim of Extreme Rights for States (available via a link from the EDSITEment resource American Memory)—such as in the Kentucky Resolutions, on the EDSITEment-reviewed website The Avalon Project—and Nullification and Secession.

Selected EDSITEment Websites

Standards Alignment

View your state’s standards

|