|

II. Key Content Areas for the

Workshops

While each workshop was customized to

meet the needs of the individual States,

in fact, some

standardized subject areas were covered

by the workshops on issues ranging from

Medicaid,

SCHIP, managed care contracting, and their

relationship to maternal and child health

programs.

Each of the trainings was a mixture of

didactic presentations by the facilitators,

discussions led

by the facilitators, and group problem

solving. The pages that follow in this

section contain the

standardized information that was transmitted

at the workshops. See the Appendices for

the

background information specific to each

of the States visited.

Medicaid and SCHIP Policies to

Improve Child and Family Health

-

Medicaid is a leading purchaser of pediatric

care. It is a source of coverage for

one out of

every five U.S. children, including

more than one-third of births. Seen

in another light, the

program covers 60 percent of poor children

younger than 18 and nearly half of births

to low

income women.

-

Children need coverage and benefits

tailored to their unique needs and designed

to foster

their health, growth, and development.

Medicaid’s Early and Periodic

Screening, Diagnosis,

and Treatment (EPSDT) package of benefits

and services are specifically designed

to fit with

pediatric clinical standards and children’s

health needs.

-

With Medicaid, poor children's access

to health care is similar to that of

non-poor, privately

insured children.

-

Millions of uninsured children are eligible

for, but not enrolled in, publicly financed

health

coverage through Medicaid or SCHIP.

Effective outreach and enrollment can

make a

difference in coverage levels.

-

Children are half of all Medicaid enrollees,

but represent only 16 percent of the

total program

spending primarily because they use

less expensive, primary and preventive

services. The

average per capita Medicaid cost for

a child is approximately $1,150, compared

to more than

$10,000 per elderly enrollee.

-

In more than half of the States, Medicaid

has been used to expand health coverage

beyond

traditional groups. Under current Federal

law, Medicaid can be used to cover millions

more

children and their parents.

-

SCHIP offers no individual legal entitlement

to a federally defined benefit. In the

35 States

that maintain separately administered

SCHIP programs, child health benefits

vary. States are

obligated to use their funds to purchase

coverage known as “child health

assistance,” making

separately administered SCHIP plans

a form of premium support, with broad

discretion given

to contracting health plans.

Managed Care and Children

An increasing number of children receive

health coverage and services through Medicaid

or

SCHIP managed care arrangements.

- Overall,

more than half of all Medicaid beneficiaries

are enrolled in some form of managed

care in all States and the District

of Columbia, except Alaska and Wyoming.

- Children

are the group in Medicaid most likely

to be required to enroll in managed

care.

Children are more likely than beneficiary

groups such as the elderly, pregnant

women, adults

with disabilities to be included in

mandatory managed care enrollment rules

under Medicaid.

-

In 1998, more than half (55 percent)

of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in

managed care

were children under age 21. Many SCHIP

eligible children are enrolled -- on

a voluntary or

mandatory basis -- in managed care arrangements.

- Children

in Medicaid SCHIP plans are entitled

to the same benefits and protections

as

children in regular Medicaid plans.

- Among

26 States using separate, non-Medicaid

SCHIP and comprehensive managed care

in

2000, 11 States integrate the SCHIP

managed care contract with the Medicaid

contract.1

The promise of managed care is that it

can reduce costs to purchasers while improving

health

outcomes for the insured individual. Managed

care organizations (MCOs) seek to fulfill

this

promise through three basic mechanisms:

organizing provider relationships, limiting

what will be

covered, and controlling enrollee access

to services. Controls on access to service

generally are

aimed at high-cost and unnecessary services

(e.g., some elective surgery, and emergency

department use for routine care).2

In theory, MCOs also will seek to ensure

necessary care,

which can help enrollees remain healthy

and reduce long-term costs. In practice,

MCOs’ limits

on care are more frequent than promotions

for utilization of health services, primarily

because

they have greater incentives to reduce

short-term than long-term costs. For children,

such

emphasis on short-term results is a disadvantage.

Improving Child Health Access

and Outcomes through Effective Managed

Care

Contracting

Managed care arrangements are defined

in contracts between the purchaser and

the MCO, as

well as between the managed care organization

and its network providers. The contract

between

the MCO and the purchaser – in this

case the State Medicaid or SCHIP Agency

– sets the

boundaries on what services will be delivered,

when, and how. As use of managed care

has

increased, contracts have become an increasingly

important part of the legal and regulatory

framework under which children and families

receive health care. (See Figure A).

Solid managed care contracts are based

on negotiation and an agreement that reflects

“a meeting

of the minds.” Success depends on

clearly defining the terms of the contract,

specifying the

performance objectives and measures, and

using multiple enforcement tools with

varying levels

of severity. When State governments are

the purchasers, contracts also should

specify the nature

of the agreements and interactions expected

between MCOs and various public programs

(e.g.,

local health departments, WIC Supplemental

Food Program sites).

[D]

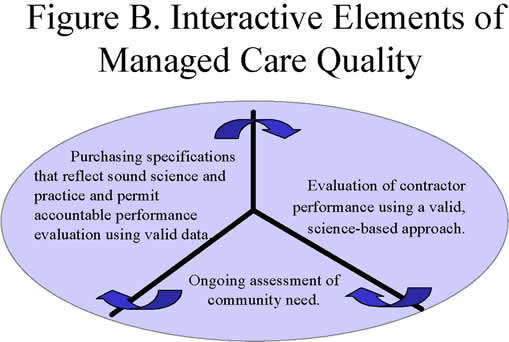

Managed care contracts are a particularly

useful tool for States to use in efforts

to improve health

care quality. (See Figure B.) State Medicaid

or SCHIP Agencies cannot overcome certain

systemic barriers to effective pediatric

preventive care, such as constraints on

access to care,

inadequate provider training and practice,

or deficits in parental knowledge and

parenting skills.

States can, however, set out expectations

for quality and, in turn, monitor quality,

pay for

performance, or penalize those who do

not perform.

Managed care contracts represent a unified

policy Statement by the State and are

the principal

means to create legally binding agreements

with managed care organizations (MCOs).

Contracts,

and the negotiations around contracts,

are the means for working out some very

specific

challenges in the delivery system. Furthermore,

if a benefit, quality standard, or other

expectation is not in the contract, MCOs

and their providers cannot be expected

to meet the

State’s expectations. Contracts

are also useful for policy makers, as

a means to express

priorities. If the State’s contract

development process is inclusive, it creates

inter- and intradepartmental

communication about the inter-relationship

of categorical and entitlement

programs. Such processes force categorical

programs to think about adapting their

programs to

an evolving health care delivery and financing

system. Finally, well-expressed contracts

set the

framework for communication with beneficiaries

(covered persons), including what should

be

contained in enrollment materials, how

people can engage in grievance processes,

and what

protections exist for those involuntarily

disenrolled.

[D]

Managed Care Contracts and Child

Health

A series of analyses of States’

Medicaid managed care contracts by GWU

researchers 3

found that such contracts express a vision

of health care and the health care system,

not

merely health coverage. As State Medicaid

Agencies become more sophisticated health

care purchasers, contracts have become

larger and more complex. Increasingly,

States include

detailed specifications that emphasize

the structure and process of care. Contracts

are

generally comprehensive and specific in

the areas of networks, access, service

delivery,

quality improvement, data collection and

reporting, consumer protections, and provider

payments. At the same time, States continue

to make fairly limited use of provisions

regarding

resolution of conflicting treatment decisions

in the case of contractors and agencies

responsible

for the same member. Detailed analysis

of contract provisions on pediatric care

found that State Medicaid

managed care contracts generally have:

-

Merged coverage and care into comprehensive

specifications that give attention to

pediatric care delivery -- not just

coverage.

-

Increased specificity regarding services

for special populations, such as children

with

special health care needs.

-

Attempted to close the gap between Federal

requirements and State contracts.

-

Not often met the challenge of incorporating

the broad EPSDT benefits into contracts,

despite greater attention to child health.

-

Specified the inclusion of "pediatric

providers" in the managed care

network.4

Table

1. Pediatric Purchasing Specifications:

Table of Contents

Part I Items and Services Covered

101- Medicaid Items and Services

101-A. Coverage Determination Standards

and Procedures

101-B. Delivery of Covered Items and

Services

102- EPSDT

103- Prescription Drugs

104- Family Planning Services and

Supplies

105- Medicaid Items and Services Not

Covered

106- Dental Services

107- STD Services

108- HIV Services

109- TB Services

110- Childhood Lead Poisoning Services

111- Diabetes Services

Part 2 Enrollment and Disenrollment

Part 3 Information for New and Potential

Enrolled Children

Part 4 Provider Selection and Assignment

Part 5 Provider Network

Part 6 Access Standards

Part 7 Relationships with Other State

and Local Agencies

Part 8 Quality Measurement and Improvement

Part 9 Data Collection and Reporting

Part 10 Enrolled Child Safeguards

Part 11 Vaccines for Children Program

Part 12 Remedies for Noncompliance

Part 13 Other Applicable Federal and

State Requirements

Part 14 Definitions |

Pediatric Purchasing Specifications

GWU has prepared purchasing specifications

to assist State agencies, private purchasers,

and

others interested in improving managed

care contract provisions. The Medicaid

Pediatric

Purchasing Specifications include numerous

provisions addressing a wide range of

issues for

Medicaid-eligible children and adolescents.

The purchasing specifications are based

on an understanding of existing contract

provisions

(such as those in the Medicaid managed

care contract database), as well as review

by Federal and

State government agencies, issue content

experts, and consumer advocates.

The GWU Pediatric Purchasing Specifications

are not official government policies and

do not

define a right and a wrong way to set

up contracts. They do provide advice on

how to construct

contract provisions so that they accurately

and precisely reflect the intentions and

expectations of

those who purchase managed care coverage.

They give options and alternatives based

on legal or

clinical guidelines -- they do not indicate

a single "correct" course of

action. The Purchasing

Specifications are designed for “plug

and play” to address key issues

in the context of a larger

purchasing process in a specific State

context. Thus, they can assist Medicaid

and SCHIP

agencies operating in different health

systems and under different State policies.

Purchasing specifications might be used

as a checklist for comparing contract

language, as a

source for examples of legally accurate

provisions, or as a way to explore specific

contract issues

in greater depth. The following examples

illustrate how purchasing specifications

might be used

by different agencies.

State Maternal and Child Health (MCH)

Programs may wish to use the Pediatric

Purchasing

Specifications to:

-

Raise maternal and child health issues

with the State Medicaid agency;

-

Integrate appropriate public health

surveillance activities -- such as immunization

registries

or birth defects surveillance -- with

managed care efforts;

-

Clarify the role of Programs for Children

with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN)

in

financing extra items and services for

Medicaid beneficiaries under age 21;

-

Ensure that quality standards appropriate

to children's unique developmental,

physical, and

mental health needs are reflected in

the contract;

-

Ensure reimbursement for Medicaid-covered

services provided through local health

or early

intervention agencies (under Part C

of IDEA); and

-

Define linkage and referral mechanisms

between outreach and home visiting programs

for

families with young children.

State Medicaid Agencies may choose to

use pediatric specifications to:

-

Maximize the value of purchasing Medicaid

or SCHIP coverage for children;

- Better

define standards and expectations of

MCOs, particularly under the EPSDT benefit

for

children and services for children with

special health care needs;

- Better

define services that go into determination

of a capitation rate for Medicaid or

SCHIP,

particularly the EPSDT benefit for children

and services for children with special

health care

needs;

- Better

define performance expectations of MCOs,

beyond typical measures such as

immunization or prenatal care rates;

- Define

the outreach, informing, and support

services required under EPSDT, clarifying

and

specifying the expected role of MCOs;

- Better

integrate Medicaid or SCHIP managed

care with other publicly supported services

such as early intervention for infants

and toddlers, school-based health services,

home

visiting, or mental health services;

- Assist

in reducing overall State spending by

avoiding unnecessary public health expenditures

for children enrolled in Medicaid or

SCHIP (e.g., immunization, lead poisoning,

transportation, or case management);

and

-

Focus on selected outcomes to improve

health and reduce costs in areas such

as obstetrical

risk management, early childhood developmental

screening, or preventive services to

adolescents.

Having clear and specific contracts is

key to optimal service for children and

families enrolled in

managed care plans. The Pediatric Purchasing

Specifications are a tool to assist with

improving

contract language. Each player in the

health care system has a role to play.

Suggestions for

using the pediatric purchasing specifications

to improve contract provisions related

to pediatric

care are shown in Table 2.

Table

2. A Contract Review Tool for Purchasing

Child Health Services in Medicaid

Managed Care

Does your State’s Medicaid

managed care contract:

-

Specify pediatric services covered,

including items necessary to prevent,

correct, or ameliorate a condition,

disability, illness, or injury

or to promote growth and developmental,

or to maintain functioning.

-

Specify coverage of recommended

childhood immunizations without

prior authorization.

-

Specify coverage of items and

services for an enrolled child

under an Individualized Family

Services Plan (IFSP) or an Individualized

Education Program (IEP) developed

by an agency under the Individuals

with Disabilities Education Act

(IDEA)

-

Specify coverage of dental services.

-

Reference "Bright Futures:

Guidelines for Health Supervision

of Infants, Children, and Adolescents"

or other applicable medical

and dental association guidelines.

-

Prohibit prior authorization with

respect to comprehensive well-child

(EPSDT) screens based on a State’s

periodic visit schedule, as well

as interperiodic visits not on

the schedule.

-

Prohibit denial of coverage for

newborns due to a "pre-existing

condition" according to the

Newborns' and Mothers' Health

Protection Act of 1996.

-

Require that plans offer the family

or caregiver of a child with special

health care needs the option of

designating as the child's primary

care provider a pediatric

specialist participating

in the provider network as described

in enrollee information materials.

-

Require that safety net providers

be included in provider networks.

-

Require timely access to pediatric

services, including an initial

assessment of an enrolled child

conducted by a primary care provider

using the standards of Bright

Futures.

-

Specify elements for Memorandum

of Understanding (MOU) defining

relationships between the contractor

and public health departments,

Title V agency, SCHIP agency,

child welfare agency, State and

local education agencies, developmental

disabilities agency, and mental

health and substance abuse agency.

-

Specify use of quality measures

or studies appropriate for children.

-

Specify that the contractor shall

collect and report to the purchaser

on underutilization of services

by enrolled children.

-

Require that contractor ensure

each provider furnishing covered

immunizations participate in the

Vaccines for Children Program.

-

Specify remedies for noncompliance

or nonperformance, such as withholding

payments, suspension of enrollment,

or money penalties.

Source: George Washington University

Center for Health Services Research

and Policy. Pediatric Purchasing

Specifications Module © 2001 |

1

Rosenbaum S and Markus AR. Policy

Brief #2 "State Benefit Design Choices

under SCHIP: Implications for

pediatric health care. Washington,

DC: The George Washington University,

2002.

2

Rosenbaum S, et al. Negotiating the

New Health System: A nationwide study

of Medicaid Managed Care

Contracts. (First Edition) Washington,

DC: The George Washington University,

1997.

3

Rosenbaum S, et al. Negotiating the New

Health System: A nationwide study of Medicaid

Managed Care

Contracts. First Edition, 1997; Second

Edition, 1998; Third Edition, 1999; Fourth

Edition, 2001. Washington, DC:

The George Washington University.

4

Rosenbaum S, Sonosky CA, Shaw K, et al.

Negotiating the New Health System: A nationwide

study of Medicaid

Managed Care Contracts. Third Edition,

Vol. 1, 1999. Washington, DC: The George

Washington University. |