|

||

|

||

|

|

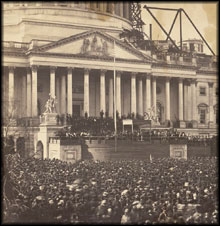

The First Inaugural Address (1861)—Defending the American UnionLesson Plan Two of the Curriculum Unit: "A Word Fitly Spoken": Abraham Lincoln on the American UnionIntroduction"Plainly, the central idea of secession, is the essence of anarchy." With this statement, Abraham Lincoln tried to show why the attempt of seven states to leave the American union peacefully was, in fact, a total violation of law and order. The Constitution required that the newly elected president of the United States take an oath to "preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States," and so Lincoln explained how he would keep that Union together. Exactly one month before Lincoln delivered his First Inaugural Address on March 4, 1861, a provisional Confederate States of America had already drawn up a constitution and elected officers. Moreover, the departing president, James Buchanan, added to the new president's difficulties. While his December 1860 State of the Union Address argued that secession was not "an inherent constitutional right," Buchanan saw no constitutional provision that empowered the president "to coerce a state into submission."Lincoln read the federal constitution differently, stating "the declared purpose of the Union that it will constitutionally defend, and maintain itself." But he also affirmed that "there needs to be no bloodshed or violence; and there shall be none, unless it be forced upon the national authority." To this end, he used his inaugural address to try to mend the rift between sections of the nation that would soon go to war. Lincoln closed his First Inaugural Address by appealing to "the better angels of our nature" as his fondest hope for preserving the union of the American states. This lesson will examine Lincoln's First Inaugural Address to understand why he thought his duty as president required him to treat secession as an act of rebellion and not a legitimate legal or constitutional action by disgruntled states. This lesson will especially aid teachers of AP U.S. History classes by augmenting student knowledge and evaluation of a decisive time in U.S. history, listed in the Course Description as "Abraham Lincoln, the Election of 1860, and Secession," a subtopic under "The Crisis of the Union." The learning activities will strengthen the higher order thinking skills students will need to do well on the AP exam, particularly the DBQ and essay part of the exam, by guiding them through successive levels of thought, from knowledge and comprehension of concepts like federalism, states' rights, national sovereignty, perpetual union, and secession, to analysis and evaluation of these issues in the context of making a persuasive argument. Guiding QuestionHow did Lincoln defend the American union from states seeking to leave or "secede" from the Union?Learning ObjectivesAfter completing this lesson, students should be able to:

Background Information for the TeacherAt the time that Lincoln delivered his First Inaugural Address, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union and set up a provisional government. Lincoln's Address reassured them and the rest of the South that he had no intention of interfering with their "domestic institutions" (meaning slavery), but Southerners remained vexed with their own economic and political concerns. While cotton was still "king" of the Southern economy, the cost of producing cotton had risen because the price of slaves, needed to harvest the crop, had gone up dramatically in the past twenty years. Even the average farmer felt the pinch, as small plots were being consolidated into larger agricultural enterprises, making it more difficult for lesser-income Southerners to make a living. Efforts to industrialize and diversify the economy had also largely failed.In addition, the South felt increasingly isolated on the political front, especially when the Democratic National Convention in April 1860, led by the eventual nominee of the Northern Democrats, Stephen A. Douglas, refused to endorse a federal law protecting slavery in the federal territories. Southerners walked out of the convention. After a second convention in June failed to reconcile these opposing interests, Southerners bolted again and drafted a separate platform. For President they nominated the vice president under James Buchanan, Kentucky Senator John C. Breckenridge. But this turned them into a regional party. In fact, the electoral returns of 1860 showed it to be a regional election across the board, with the Republican Party as the party of the North and Northeast. When the victorious Republicans suggested a modest protective tariff—something that had long been opposed in the South—Southerners became convinced that their concerns were not appreciated by the party now in power in the executive branch. Because Northerners had elected someone from a party hostile to the interests of the South, Southerners thought that the Union had made the first move in cutting them adrift: the Union had left the South "in sympathy," so seven Southern states responded by leaving the Union "in fact" by seceding. The first Republican president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, drew less than forty percent of the popular vote, though he received a clear majority of the electoral votes (180 out of 303)—all from Northern, free states. His leadership of a party opposed to the spread of slavery led to his name being left off the ballots of nine Southern states (where no Republican Party surfaced). Southerners therefore viewed Lincoln and the Republicans as representing sectional interests in opposition to those of the slaveholding states, who claimed to uphold the constitutional rights of all property owners. Although Lincoln hated slavery and consistently argued against its expansion into federal territory, he was not an abolitionist; he disagreed with those who would promote emancipation at the expense of preserving the Constitution and the rule of law. He acknowledged the legal right to own slaves under state constitutions that already permitted the "peculiar institution," which the Constitution respected through compromises that helped produce "a more perfect union." Lincoln also recognized the fragile condition of the country, and therefore did not seek the repeal of the notorious (but constitutional) Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required that escaped slaves be returned to their masters in the South. Lincoln used his inaugural address to declare his constitutional intentions as the incoming president, especially given the anxiety in the Southern states over the protection of their slaves, and to explain the nature of the national union. He announced that he would not interfere with slavery where it already existed, and pledged to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act—a key issue for seceding states, who complained that Northern states obstructed the enforcement of this act by passing personal liberty laws. Lincoln then declared that "the Union of these States is perpetual" and added that "no State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union." Why? First, all national governments by their nature existed in perpetuity; second, even if one assumed that the United States was "not a government proper," but an "association of States," all the States would need to agree to dissolve the association, not just those who found reason to do so unilaterally; and third, the existence of the American Union preceded the Constitution, demonstrating that the States intended to act as a union at every pivotal stage of their development. Alluding to Article II of the Constitution, Lincoln considered his "simple duty" to make sure "that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States." Specifically, he intended to occupy federal property and collect duties, but for the time being not fill federal offices with "obnoxious strangers" in areas hostile to the government. Prior to his inauguration, Lincoln argued repeatedly on behalf of the natural rights of all human beings, including American slaves. He thought a concern for "the individual rights of man," and not just self interest, should inform majority rule. But given the unprecedented attempt at secession by seven states, Lincoln focused his inaugural address on what he hoped was a less controversial argument for preserving the Union: namely, the rule of law. The crux of his argument was his definition of secession as "the essence of anarchy." Lincoln was a firm believer in majority rule constrained by "constitutional checks" and informed by public opinion. Rule by any other principle or practice, he explained, would only lead to anarchy or despotism. He added that any disagreement between the sections could be resolved better within the Union than as separate entities. Closing the address with an appeal to "the better angels of our nature," Lincoln hoped that passion would give way to reason, and that the Union would restore its luster in the eyes of a divided nation. Preparing to Teach this Lesson

Suggested ActivitiesActivity: Debating Lincoln's views of the UnionThis lesson is built around the following sequence of tasks:

Debate: Is the Union of American States Permanent and Binding, or Does a State Have the Right to Secede? Students will debate the central questions of this lesson: Once the citizens of a state join the Union, are they permanently, perpetually bound to the other states? Or does a state then have the right to secede from the Union? In other words, what is the nature of the Federal Union? Make clear to students that they should hold these questions in mind as they undertake their primary source analysis and the debate that follows. Students will read primary source material and answer questions about those documents in preparation for a debate. As Lincoln's First Inaugural Address is the focus of this lesson, all students will read this text first. Then the class will be divided into three teams: two to debate the opposing sides and one to act as judges by evaluating the debate and declaring a winner. The first two teams will be given separate readings to prepare for the debate: one side will argue the pro-Union point of view and the other side will argue the pro-secession point of view. The third team will be given the readings of both the pro-Union and the pro-secession sides so that they can become familiar with the content that will be debated. Before the Classroom Lesson Begins"The Union of these States is Perpetual": Lincoln's View of the American UnionIn the class period before this lesson begins, assign the reading of Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address to all students for homework, and have them answer the four questions that follow below, which are available in worksheet form on page 5 of the Text Document. A link to the First Inaugural Address can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site American President of the Miller Center of Public Affairs (University of Virginia). A shorter excerpt of Lincoln's First Inaugural Address is available in worksheet form on pages 1-4 of the Text Document. Students should bring Lincoln's Inaugural Address and their answers to the questions to class the following day.

Preparation for the Debate

Unionist GroupFor the pro-Union side of the debate, students will read excerpts from the Constitution, in addition to re-reading Lincoln's First Inaugural Address."On the Execution of His Office": What the Constitution Expects of the President Have the pro-Union students read the Preamble, Article II (Sections 1-3), and Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, which deal with the executive power and the nature and purpose of the federal constitution. Then have them answer in their group the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 7 of the Text Document. A link to the Constitution can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "The Charters of Freedom" of the National Archives. The relevant sections of the Constitution are also included in the Text Document on page 6, and can be printed out for student use.

Finally, have these students read Lincoln's First Inaugural Address again, and answer in their groups the additional questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 8 of the Text Document.

Secessionist GroupFor the pro-secession side of the debate, students will read excerpts from South Carolina's "Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union" and a Louisiana newspaper editorial."Released from Her Obligation": South Carolina Decides to Leave the Union Have these students read an excerpt from South Carolina's "Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union" (December 20, 1860) and answer in their groups the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on pages 12-13 of the Text Document. A link to South Carolina's Secession Declaration can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site "The Avalon Project." The relevant Secession Declaration excerpts are also included in the Text Document on pages 9-11, and can be printed out for student use.

Next, have students read the New Orleans Daily Crescent editorial, "The Policy of Aggression" (located at the EDSITEment-reviewed site Teaching American History), and answer in their groups the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 16 of the Text Document. The editorial is also included on pages 14-15 of the Text Document, and can be printed out for student use.

The JudgesAs the two groups above are answering questions in preparation for the debate, students in this group—subdivided into smaller groups if necessary—will be reading the documents of both sides. In collaboration with each other, they will make a list of the strongest points of each side of the argument that they will be listening for during the debate. If students in this group do not finish compiling their main points during Day One, they can be assigned the rest of the reading and analysis for homework. They can also continue their work during the first part of Day Two, when the other two teams are choosing their speakers and consulting with each other on their best arguments.Let the Debate Begin! The Nature of the Federal Union—Does a State Have the Right To Secede?On Day Two, students will engage in a debate concerning the nature of the federal union: Is the Union of the states perpetual, permanent, and binding, or does a state have the right to secede or break away from the Union?The two sides in this debate will arrange their desks so that each team faces the other with some space opened up in the middle of the floor. Each of the first two teams, the unionist and secessionist sides, chooses three speakers, one to make the main points of the argument (principal speaker), one to focus attention on one or two key points (second speaker), and one to summarize the argument (summarizer). With answers to their questions at hand, each side helps its speakers to develop their arguments. If the class is too large to make this feasible, have each side divide into three groups, with one speaker in each group. Each small group will then help its speaker to develop his or her argument. When it is time for the debate to begin, seat the judges off to the side, between the two groups, where they can view and hear the proceedings. Make sure the judges understand that the outcome of the debate is to be decided on the merits of the arguments themselves: that is, on the basis of which team made the better case for explaining the nature of the federal union. Emphasize to the students that this is not a debate about slavery or who won the war; it is a debate about which argument better comprehends how the states are joined together as a nation. Give the principal speaker for each side an allotted amount of time to make his or her speech. Do the same for the second speakers (usually less time than the first). Then throw the debate open, in the British style, so that team members from each side can question or direct comments to the other side. Alternate this process back and forth several times, as interest requires or time permits, so that each side has an equal chance to state their views. The summarizer concludes the debate by making the team's best case, using the earlier input from his team and the strongest points of the team's two speakers and the open debate. The judges then take a vote among themselves to determine the winner of the debate. Before telling the outcome to the two teams, they should give the class the strongest points made by each side of the debate. AssessmentHave students answer, in a well-constructed paragraph or two, some or all of the questions below:

Extending the LessonNo "Power to Make War Against a State." What the Exiting President Advised Regarding Secession.Have students read excerpts from President James Buchanan's "State of the Union Address" (December 3, 1860), and answer the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 7 of the "Extending the Lesson" Text Document. A link to James Buchanan's State of the Union Address can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site Teaching American History. A shorter excerpt from the speech is also included in the Text Document on pages 1-6 of the "Extending the Lesson" Text Document, and can be printed out for student use.

Although Lincoln entered politics as a Whig opponent of Democratic President Andrew Jackson, Lincoln agreed with Jackson's 1832 opposition to nullification and secession and borrowed from Jackson's "Proclamation Regarding Nullification" when he prepared his First Inaugural Address. According to Lincoln's law partner, William H. Herndon, the president-elect wrote the first draft of his inaugural address in Springfield, Illinois, consulting four reference works: "He asked me to furnish him with Henry Clay's great speech delivered in 1850; Andrew Jackson's proclamation against Nullification; and a copy of the Constitution." On November 24, 1832, in response to federal tariffs seen as favoring northern manufacturers against southern agricultural interests, South Carolina issued an Ordinance of Nullification declaring these tariffs "null, void, and no law, nor binding upon this State." The State also claimed a right to "organize a separate government," i.e., to secede, because its leaders believed that the federal union existed as a compact or league of states. In a "Proclamation Regarding Nullification" (December 24, 1832), Andrew Jackson rejected this claim to a right of nullification and the notion that the federal union was merely a league of states. Have students read an excerpt from Andrew Jackson's Proclamation and answer in their groups the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 10 of the "Extending the Lesson" Text Document. A link to Jackson's Proclamation Regarding Nullification can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site The Avalon Project. The relevant Proclamation excerpts are also included on pages 8-9 of the "Extending the Lesson" Text Document, and can be printed out for student use.

After initially exhorting his home state of Georgia not to secede, Alexander Stephens eventually defended the secession of the Deep South and anticipated additional states would join. (The Confederate States of America would eventually include eleven states: in order of secession, South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.) As Confederate Vice President, Stephens delivered what is known as the "Cornerstone Speech" about two weeks after Lincoln's First Inaugural Address. Have students read excerpts from Alexander Stephens's "Cornerstone Speech" (March 21, 1861), and answer the questions that follow, which are available in worksheet form on page 14 of the "Extending the Lesson" Text Document. A link to Alexander Stephens's "Cornerstone Speech" can be found at the EDSITEment-reviewed site Teaching American History. A shorter excerpt from the speech is also included in the Text Document on pages 11-13 of the "Extending the Lesson" Text Document, and can be printed out for student use.

Previous Lesson PlanNext Lesson PlanReturn to the Curriculum Unit Overview: "A Word Fitly Spoken": Abraham Lincoln on the American UnionRelated EDSITEment Lesson Plans

Selected EDSITEment Websites

Standards Alignment View your state’s standards |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||

| EDSITEment contains a variety of links to other websites and references to resources available through government, nonprofit, and commercial entities. These links and references are provided solely for informational purposes and the convenience of the user. Their inclusion does not constitute an endorsement. For more information, please click the Disclaimer icon. | ||

| Disclaimer | Conditions of Use | Privacy Policy Search

| Site

Map | Contact

Us | ||