|

||

|

||

|

|

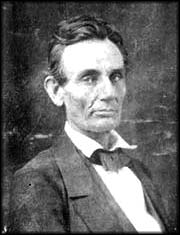

Abraham Lincoln, the 1860 Election, and the Future of the American Union and SlaveryLesson Plan Four of the Curriculum Unit: A House Dividing: The Growing Crisis of Sectionalism in Antebellum AmericaIntroductionThis lesson plan will explore Abraham Lincoln's rise to political prominence during the debate over the future of American slavery. Lincoln's anti-slavery politics will be contrasted with the abolitionism of William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass and the "popular sovereignty" concept of U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas. The views of southern Democrats like Jefferson Davis and William Lowndes Yancey will also be examined to show how sectional thinking leading up to the 1860 presidential election eventually produced a southern "secession" and the American Civil War. In addition, the Republican Party platform of 1860 will be compared with the platforms of the two Democratic factions and the Constitutional Union Party to determine how the priorities of Lincoln and his party differed from the other parties in 1860, and how these differences eventually led to the dissolution of the Union. Guiding Questions

Learning ObjectivesUpon completion of this lesson, students should be able to:

Background Information for the TeacherWhat follows are brief descriptions of the key figures (and their related political parties) leading up to the 1860 presidential election: William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) was an abolitionist orator and editor of The Liberator. He began as a moderate abolitionist, arguing for gradual emancipation and somewhat open to colonization of black Americans. But his association with Quaker abolitionist Benjamin Lundy brought a greater urgency and fervor to Garrison's abolitionism. He believed the U.S. Constitution was more hindrance than help in the cause of emancipation because it tolerated slavery in southern states and called it "a covenant with death and an agreement with hell." By 1844, Garrison and his American Anti-Slavery Society welcomed disunion so free states would not have to enforce the federal fugitive slave law and no longer have to work with slaveholding states. He employed an inflammatory rhetoric that made rebuke rather than persuasion the hallmark of his appeals to the nation's conscience. "I have need to be all on fire," he once remarked, "for I have mountains of ice about me to melt." Despite his militant abolitionism, he was a pacifist who did not believe politics or any coercion could achieve God's purposes on earth. Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was an escaped slave who joined William Lloyd Garrison as an abolition speaker and journalist. They eventually parted ways when he rejected Garrison's pro-slavery view of the Constitution. "I hold that in the Union," Douglass wrote in 1855, "this very thing of restoring to the slave his long-lost rights, can better be accomplished than it can possibly be accomplished outside of the Union." Douglass acknowledged the constitutional compromises with slavery, at least in its application, but he viewed it as a document that "leaned toward freedom." He argued that a pro-liberty interpretation of the Constitution committed the federal government to no more concessions to the southern slaveholding interest. That said, after Lincoln's election, Douglass did toy with the idea of accepting southern secession so that renegade runs into the South ("the John Brown way") could spur the liberation of fugitive slaves, who would no longer be returned from the North. During the Civil War, he was perhaps Lincoln's most famous loyal opposition, urging him at every stage of the conflict to do more for emancipation and to arm the freedmen. He eventually considered Lincoln the savior of both the Union and black Americans. Stephen Douglas (1813-1861) believed that his "popular sovereignty" policy, enshrined in the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act see Lesson Plan Three in this unit, (The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854), solved the slavery controversy by removing it from national discussion and placing it in the hands of the territorial settlers themselves. What could be more American, more democratic, than what he called "the sacred right of self-government"?! He believed that this also positioned him as the only truly national candidate for the presidency. After all, the Republican Party stood with the abolitionists against slavery, which made them a sectional (northern) party due to their anti-southern slave interest. Similarly, southern Democrats sought stronger federal protection of slavery in all federal territories, making them a sectional faction—a conviction that eventually led to their bolting from the first national Democratic Convention in 1860. In short, Stephen Douglas was a free-state Democratic senator and 1860 Northern Democratic presidential nominee who believed the following about slavery and the Constitution, and the American union: (1) neutral toward slavery, i.e., his "don't care," federal non-intervention policy toward slavery in the territories; (2) pro-Constitution with a "popular sovereignty" interpretation of self-government that applied at the territorial level as well as the state level, with Congress leaving states and now territories to protect or exclude slavery as they sought fit; and (3) pro-Union, as witnessed by his fervent campaigning on Lincoln's behalf after he saw both that Lincoln's election was inevitable and that southern states would use his election as reason to secede from the union. Jefferson Davis (1808-1889) and William Lowndes Yancey (1814-1863) were southern, slaveholding, Democratic senators who believed in a pro-slavery Constitution to the point of demanding in 1860 that Congress protect by law the property right of a slaveholder to take his slaves into a federal territory. In addition, they supported the Constitution, but believed that states retained their sovereignty within a federal structure. This "states' rights" view held that each state delegated only a portion of its powers to the national government and thus could leave or "secede" from the union if it deemed that sufficient violations of the federal compact were committed by other states: for example, a few free states passed personal liberty laws to prevent local enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) thought that the future of self-government was at stake in how American citizens decided to resolve the slavery controversy. Against the Garrisonian abolitionists, who hoped to purify the nation of the admitted blot of slavery, Lincoln thought Americans should neither disparage the rule of law nor encourage their erring southern brethren to "secede" from or leave the Union. Nor should they adopt Stephen Douglas's "Don't Care" policy of popular sovereignty, for this would teach them that there exist no principles upon which to base their vote or their very constitutional regime. It would turn republican self-government—which is based upon the natural equality of human beings that gives rise to government by consent of the governed—into crude majoritarianism, where the only principle of governance is mere self-interest. In short, Abraham Lincoln was a former Illinois Whig congressman and 1860 Republican presidential nominee who believed the following about slavery, the Constitution, and the American union: (1) anti-slavery in principle and in practice, who argued against slavery's extension into federal territories but tolerated it where it already existed in American states as a domestic (i.e., non-federal) institution and one who hoped and worked for emancipation by state initiative and eventually a federal amendment, but emphatically not an abolitionist because they elevated emancipation above preserving the Constitution and the rule of law; (2) pro-Constitution, which he saw as a pro-liberty document, and pro-Union as long as it embodied and operated according to the principles of the Declaration of Independence. Against the view of southern Democrats like Jefferson Davis and William Lowndes Yancey, Lincoln believed in restricting the extension of slavery in hopes that this would put slavery "on the course of ultimate extinction." Specifically, he supported Congress' right to do so under the federal constitution and made this the newly formed Republican Party's reason for being, which he saw as the linchpin that secured the various elements of the fusionist party of Free-Soilers, former Whigs, and Nativists. But he acknowledged the legal right to own slaves under state constitutions that already permitted it and which the U.S. Constitution respected through compromises that helped produce "a more perfect union." To this end, Lincoln recognized both the constitutional imperative to return fugitive slaves to their claimants and the fractious condition of the country, and hence did not seek the repeal of the notorious fugitive slave act of 1850, which was part of the Great Compromise of 1850. The future would show that as president, Lincoln attempted to preserve a constitutional regime from the physical force of rebellious southerners, as well as the rhetorical force of impatient abolitionists: the former were unwilling to obey a duly-elected Republican administration, while the latter were unwilling to support a constitutional union that respected the right of southern citizens to hold slaves. Preparing to Teach this LessonThis lesson will feature Lincoln's rise to national prominence as the Republican Party's preeminent anti-slavery spokesman. In the activities below, students will contrast Lincoln's ideas with those of two abolitionists, two southern Democrats, and a northern Democrat. They will also compare and contrast the platforms of the Republican Party, the two branches of the Democratic Party, and the Constitutional Union Party during the election of 1860.Review the activities, then locate and bookmark websites and primary documents (included in the PDF files for this lesson) that you will use.

If your students lack experience in dealing with primary sources, you might use one or more preliminary exercises to help them develop these skills. The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress includes a set of such activities. Another useful resource is the Digital Classroom of the National Archives, which features a set of Document Analysis Worksheets. Suggested Activities1. Comparing Abraham Lincoln with Philosophical and Political Rivals in 18602. Comparing the Republican Party Platform with the Other Party Platforms of 18601. Comparing Abraham Lincoln with Philosophical and Political Rivals in 1860 Divide the class into four groups. All groups (1-4) will read selections from Lincoln's speeches and writings. Then each group will be given the writings or speeches of one additional political or social figure to contrast with those of Lincoln. The group assignments are as follows.

Students will read the primary texts and then answer the questions for each source. The questions are designed to show points of agreement or disagreement between the two figures in regard to the federal union, the Constitution, and the future of American slavery. The task of each group will be to read the information in the documents, discuss the questions, and come to a group consensus on the answers to the questions. Each group will appoint one or two students to speak for the group. After they have been given a sufficient amount of time, they will reassemble as a class and each group will share what it has learned with the rest of the class. Note: All of the speeches and writings used below are also available in the PDF files, along with the accompanying textual analysis worksheets and compare-and-contrast matrices, for downloading, printing and distributing to students. All Groups (1-4)1. Abraham Lincoln:Have all students read the following documents and answer the corresponding questions on pages 1-3 of the PDF.

Group 1 Assignment: William Lloyd Garrison: Have students read the following documents and answer the corresponding questions on pages 4-6 of the PDF:

Group 2 Assignment: Frederick Douglass Have students in Group 2 read the following documents and answer the corresponding questions on pages 1-3 of the PDF:

Group 3 Assignment: Stephen A. Douglas: Leader of the Northern Democrats Have students in Group 3 read the following documents and answer the corresponding questions on pages 1-3 of this PDF.

Group 4 Assignment: Southern Democrats: Jefferson Davis and William Lowndes Yancey Have students in Group 4 read the following documents and answer the corresponding questions on pages 1-3 of this PDF.

2. Comparing the Republican Party Platform with the Other Party Platforms of 1860 Groups 1-4 will now contrast the Republican Party platform with the platforms of both factions of the Democratic Party and the Constitutional Union Party. Have students read the platforms and answer the corresponding questions on pages 1-3 of the PDF:

Assessment1. Students will use the matrix provided on this PDF to demonstrate their knowledge of the differences between Abraham Lincoln and the others in this lesson regarding the American union, the U.S. Constitution, and slavery.2. Have students write a paragraph explaining one of the following ironies listed below:

Extending the Lesson1. Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857)Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) was a Supreme Court decision that held that Dred Scott, a slave, was not freed by virtue of his master taking him to reside for a while in the free state of Illinois and free territory of Wisconsin. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney added that Congress had no constitutional authority to enact the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which outlawed slavery in federal territory north of the 36º30' parallel. This meant Congress could not legislate regarding slavery in the territories, which raised a hue and cry throughout the free states of the North. For more details about Dred Scott's life and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's reasoning in his majority opinion, see the EDSITEment-reviewed weblinks Africans in America: Dred Scott's Fight for Freedom Decision of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott Case at, and Africans in America: Dred Scott case: the Supreme Court decision. 2. John Brown's Raid at Harpers Ferry (1859) John Brown (1800-1859) was a radical abolitionist who took the fight against slavery literally into his own hands. First, in retaliation against slaveholders who terrorized settlers in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1855, he and four of his sons and two accomplices killed five slaveholders in what became known as "Bleeding Kansas." Second, he attempted to foment a slave insurrection by seizing a federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859. Col. Robert E. Lee led a company of U.S. Marines to capture Brown, who was then tried and eventually hanged on December 2. Frederick Douglass said of John Brown, "His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him." For more details about how John Brown's raid of the Harpers Ferry armory shaped American attitudes in the year before the 1860 election, see the EDSITEment-reviewed weblink John Brown and the Underground Railroad. 3. 1860 Platforms Compared: Additional, Specific Questions (a) Have students read the Republican Party Platform (Abraham Lincoln, Chicago, May 16, 1860) found in the PDF for this lesson and at the EDSITEment-reviewed weblink American Memory: An American Time Capsule, and answer the following questions, which address primarily the first ten resolutions:

The Crittenden Compromise (December 18, 1860), named for Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden, was a last ditch effort to prevent state "secessions" from the Union through constitutional amendments and resolutions. These reinstated the 36º30' parallel by extending it formally to the California border and guaranteeing slavery's existence below parallel while forbidding slavery north of the parallel, and strengthened the federal government's authority to return fugitive slaves to their owners. Lincoln opposed the compromise as the incoming Republican president, and it failed to pass both the House of Representatives and the Senate. For more details about the Crittenden Compromise, see the EDSITEment-reviewed weblink Crisis at Fort Sumter: Dilemmas of Compromise (click "December 18" on the calendar for a brief description, and then click "compromise plan" for the text of Crittenden's proposed amendments and resolutions). 5. Abraham Lincoln's First Inaugural Address For Lincoln's explanation of his intentions as the incoming president of a nation where seven states had already declared their separation from the federal union, see the final printed version of Lincoln's First Inaugural Address at EDSITEment-reviewed weblink The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, and the EDSITEment lesson entitled We Must Not Be Enemies: Lincoln's First Inaugural Address. 6. Frederick Douglass's 1876 "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln" To read what is arguably the most astute appraisal of Abraham Lincoln's statesmanship by a contemporary, have students read the following excerpt from Frederick Douglass's "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln" (April 16, 1876) found at the EDSITEment-reviewed weblink, The Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress (read page 42 of the 50-page document). Have students answer the following questions:

Previous Lesson PlanReturn to the Curriculum Unit Overview-A House Dividing: The Growing Crisis of Sectionalism in Antebellum AmericaRelated EDSITEment Lesson PlansAttitudes Toward Emancipation Selected EDSITEment Websites

Standards Alignment View your state’s standards |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||

| EDSITEment contains a variety of links to other websites and references to resources available through government, nonprofit, and commercial entities. These links and references are provided solely for informational purposes and the convenience of the user. Their inclusion does not constitute an endorsement. For more information, please click the Disclaimer icon. | ||

| Disclaimer | Conditions of Use | Privacy Policy Search

| Site

Map | Contact

Us | ||