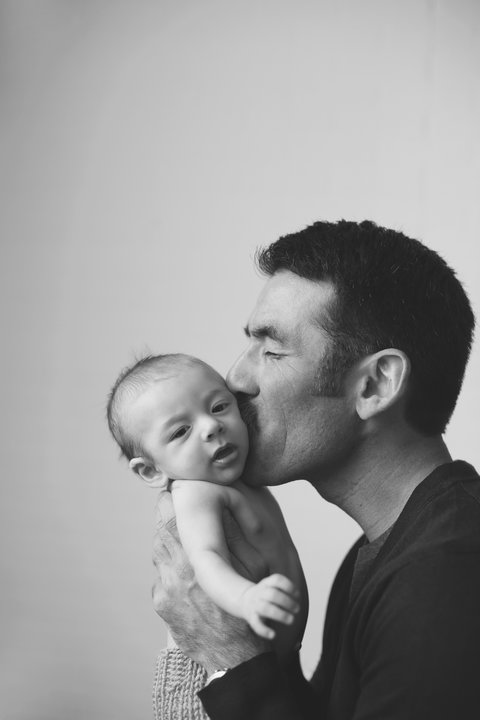

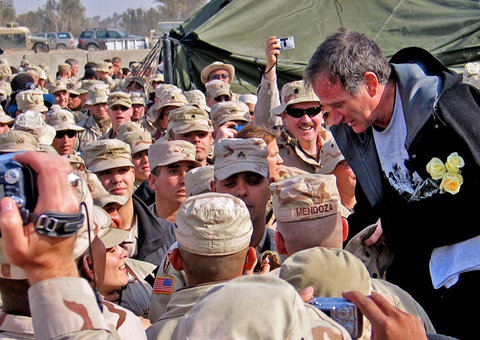

No millennial worth his iPhone remembers life before social media. While previous generations’ warfighters wrote letters or phoned home over spotty connections, Marines today can post on Instagram photos of themselves sitting atop cans of ammunition. In 2010, the photojournalist Teru Kuwayama and his collaborators embedded in Afghanistan to start a Facebook page for the First Battalion, Eighth Marines to communicate with loved ones. Far from resulting in just another live-stream of minutiae, their Basetrack project became a way for deployed troops to maintain relationships with their families. The resulting trove of photos and videos provide ample fodder for “Basetrack Live” — the onstage story of one corporal’s deployment and homecoming, and the effects on his family.

For both the battalion and a nation’s artists, self-reflection occurred stunningly quickly through the use of social media. Anne Hamburger, executive producer of En Garde Arts, the company behind “Basetrack Live,” said she felt it was important to document the human side of going to war, without sensationalizing the experience.

“The issues are so complex” when an ordinary person deploys, Ms. Hamburger said. Her biggest challenge for the production, which is showing at the Harvey Theater, Brooklyn Academy of Music, and will be going on a national tour, was paring down the “incredible wealth of material,” she said.

Ms. Hamburger reached out through Facebook, gathering more than 100 respondents and conducting three dozen interviews to cull images and video for the project. Every word in “Basetrack Live” is taken from interviews with Marines or members of their families.

This citizen journalism captures the truth of troops’ feelings during deployment, including graffiti about pornography, and profane, funny rules for standing watch and cleaning toilets. The images chosen for the production reflect the Marines’ brotherhood, including an impressive assortment of tattoos. Because of the authentic, emotion-rich material, the Marines are painted neither as heroes nor victims.

Read more...