Sleep and Health

Adequate sleep contributes to a student’s overall health and well-being. Students should get the proper amount of sleep at night to help stay focused, improve concentration, and improve academic performance.

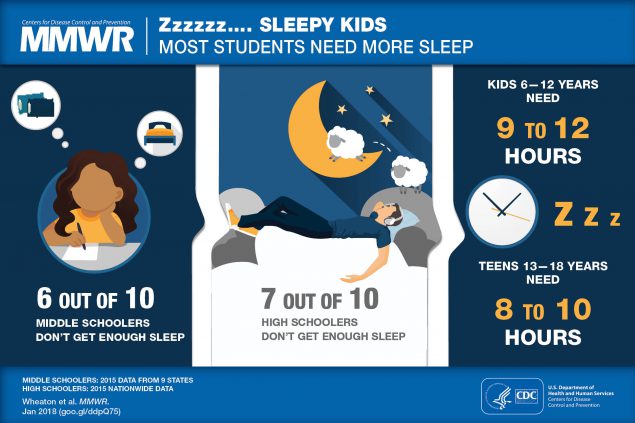

Children and adolescents who do not get enough sleep have a higher risk for many health problems, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, poor mental health, and injuries.1-4 They are also more likely to have attention and behavior problems, which can contribute to poor academic performance in school.1,2

How much sleep someone needs depends on their age. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has made the following recommendations for children and adolescents1:

| Age Group | Recommended Hours of Sleep Per Day |

|---|---|

| 6–12 years | 9 to 12 hours per 24 hours |

| 13–18 years | 8 to 10 hours per 24 hours |

The data from the 2015 national and state Youth Risk Behavior Surveys, a CDC study, shows that a majority of middle school and high school students reported getting less than the recommended amount of sleep for their age.5

Middle school students (grades 6–8)

- Students in 9 states were included in the study.

- About 6 out of 10 students (57.8%) did not get enough sleep on school nights.

High school students (grades 9–12)

- National sample.

- About 7 out of 10 students (72.7%) did not get enough sleep on school nights.