African Americans and Tobacco Use

Black or African American is defined by the Office of Management and Budget as “a person having origins in any of the black racial groups of Africa.”1 There were over 40 million African Americans in the United States in 2016—approximately 13% of the U.S. population.2

Although African Americans usually smoke fewer cigarettes and start smoking cigarettes at an older age, they are more likely to die from smoking-related diseases than Whites.3,4,5,6,7,8

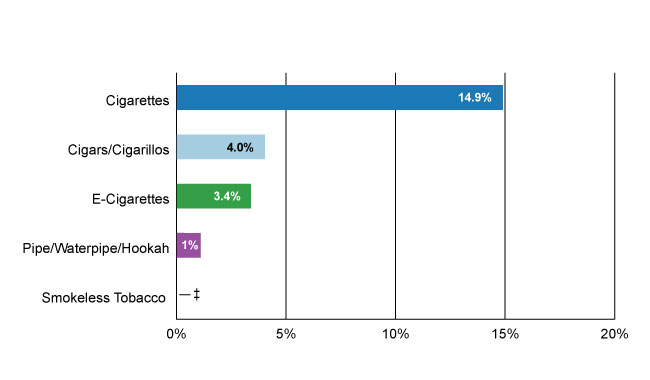

Current Tobacco Use* Among African American Adults—2019†9

* “Tobacco Use” is defined as use either “every day” or “some days” of at least one tobacco product among individuals (For cigarettes, users were defined as persons who reported use either “every day” or “some days” at the time of survey and had smoked ≥100 cigarettes during their lifetime).

† Data taken from the National Health Interview Survey, 2019, and refer to Black, non-Hispanic adults aged 18 years and older.

‡ Dashes indicate prevalence estimates with a relative standard error > 30% and are not presented.

Tobacco use is a major contributor to the three leading causes of death among African Americans—heart disease, cancer, and stroke.3,4,5

- Diabetes is the fourth leading cause of death among African Americans.4 The risk of developing diabetes is 30–40% higher for cigarette smokers than nonsmokers.10

- African American youth and young adults have significantly lower prevalence of cigarette smoking than Hispanics and Whites.11

- Although the prevalence of cigarette smoking among African American and White adults is similar, African Americans smoke fewer cigarettes per day.3,6

- On average, African Americans initiate smoking at a later age compared to Whites.3,

African American children and adults are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke than any other racial or ethnic group.12

- During 2013-2014, secondhand smoke exposure was found in:

- 66.1% of African American children aged 3–11 years.12

- 55.3% of African American adolescents aged 12–19 years.12

- 45.5% of African American adults aged 20 years and older.12

- African American nonsmokers generally have higher cotinine levels (an indicator of recent exposure to tobacco smoke) than nonsmokers of other races/ethnicities.12

Most African American adult cigarette smokers want to quit smoking, and many have tried.10,13

- Among African American current daily cigarette smokers aged 18 years and older:

- 72.8% report that they want to quit compared to 67.5% of Whites, 69.6% of Asian Americans, 67.4% of Hispanics, and 55.6% of American Indians/Alaska Natives.13

- 63.4% report attempting to quit compared to 56.2% of Hispanics, 53.3% of Whites, and 69.4% of Asian Americans.13

- Despite more quit attempts, African Americans are less successful at quitting than White and Hispanic cigarette smokers, possibly because of lower utilization of cessation treatments such as counseling and medication.3,13

Targeted Marketing

- The tobacco industry has aggressively marketed menthol products to young people and African Americans, especially in urban communities.14 Historically, the tobacco industry’s attempts to maintain a positive image among African Americans have included such efforts as supporting cultural events and making contributions to minority higher education institutions, elected officials, civic and community organizations, and scholarship programs.3

- Tobacco companies have historically placed larger amounts of advertising in African American publications, exposing African Americans to more cigarette ads than Whites.3

Menthol Cigarette Advertising

- Historically, the marketing and promotion of menthol cigarettes have been targeted heavily toward African Americans through culturally tailored advertising images and messages.14,15

- Over 7 out of 10 African American youth ages 12-17 years who smoke use menthol cigarettes16

- African American adults have the highest percentage of menthol cigarette use compared to other racial and ethnic groups.17

- Menthol in cigarettes is thought to make harmful chemicals more easily absorbed in the body, likely because menthol makes it easier to inhale cigarette smoke.3,18

- Some research shows that menthol cigarettes may be more addictive than non-menthol cigarettes.19

Price Promotions, Retail, and Point-of-Sale Advertising

- Tobacco companies use price promotions such as discounts and multi-pack coupons—which are most often used by African Americans and other minority groups, women, and young people—to increase sales.20

- Areas with large racial/ethnic minority populations tend to have more tobacco retailers located within them, which contributes to greater tobacco advertising exposure.20

- Menthol products are given more shelf space in retail outlets within African American and other minority neighborhoods.20

Culturally appropriate anti-smoking health marketing strategies and mass media campaigns like CDC’s Tips From Former Smokers national tobacco education campaign, as well as CDC-recommended tobacco prevention and control programs and policies, can help reduce the burden of disease among the African American population.

Publication

CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health sponsored a special supplement to the journal of Nicotine & Tobacco Research titled Critical Examination of Factors Related to the Smoking Trajectory among African American Youth and Young Adults. The supplement focuses on disparities in tobacco use and tobacco-related health outcomes between African Americans and Whites. Research studies in the supplement highlight that African Americans have disproportionately higher rates of several smoking-related diseases even though African Americans start smoking later in life and smoke fewer cigarettes per day than Whites. Interventions to prevent smoking initiation and facilitate quitting among African Americans can help reduce disparities in this population. In addition, addressing other broader, systemic issues such as access to health care, screening and diagnostic services, and quality of care may help reduce disparities in morbidity and mortality from tobacco-attributable disease.

Historical Publication

- Pathways to Freedom: Winning the Fight Against TobaccoThe Pathways to Freedom booklet was produced in partnership with key segments of the African-American community, including churches, service organizations, and educational institutions.

- Government Printing Office. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity, 1997 pdf icon[PDF–156 KB]external icon. [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Fact Finder, 2016external icon American Community Survey Demographic and Housing Estimates. [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2014 pdf icon[PDF–2.95 MB]. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2016;vol 65: no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Heron, M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2010 pdf icon[PDF–5.08 MB]. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2013;62(6) [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health Behaviors of Adults: United States, 2008–2010 pdf icon[PDF–3.21 MB]. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10(257) [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- American Lung Association. Too Many Cases, Too Many Deaths: Lung Cancer in African Americans pdf icon[PDF–1.68 MB]external icon. Washington, D.C.: American Lung Association, 2010 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan C, Neff L. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults – United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2020. Volume 69(issue 46); pages 1736–1742. [accessed 2020 November 19].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2015;64(14):381–5 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Tsai J, Homa DM, Gretzke AS, et al. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Among Nonsmokers — United States, 1988–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2018;67(48);1342–1346 [accessed 2019 Nov 18].

- Babb S, Malarcher A, Schauer G, et al. Quitting Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2000–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2017;65(52):1457-64 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes [PDF–1.6 MB]external icon. 2013.

- National Cancer Institute. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Useexternal icon. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19, NIH Pub. No. 07-6242, June 2008 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Gardiner PS. The African Americanization of Menthol Cigarette Use in the United States. Nicotine and Tobacco Research 2004; 6:Suppl 1:S55-65 [cited 2018 Jun 12].

- Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD et al. Differential Trends in Cigarette Smoking in the USA: Is Menthol Slowing Progress? Tobacco Control, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159, August 30, 2013 [cited 2018 Jun 12].

- Ton HT, Smart AE, Aguilar BL, et al. Menthol enhances the desensitization of human alpha3beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 2015;88(2):256-64 [cited 2018 Jun 12].

- Smokefree.gov. Menthol Cigarettesexternal icon. Bethesda (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2015 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

- Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Strategies: A Tobacco Control Guide pdf icon[PDF–15.6 MB]external icon. St. Louis: Center for Public Health Systems Science, George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis and the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, 2014 [accessed 2018 Jun 12].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.