Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Persons and Tobacco Use

People who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) include all races and ethnicities, ages, and socioeconomic groups, and come from all parts of the U.S. It is estimated that lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) persons make up approximately 3% of the total U.S. population.1

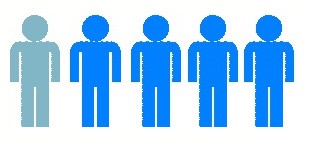

Cigarette smoking among LGB individuals in the U.S. is higher than among heterosexual/straight individuals. About 1 in 5 LGB adults smoke cigarettes compared with about 1 in 6 heterosexual/straight adults.2

20.5% of LGB adults smoke cigarettes compared to 15.3% of straight adults.2

* Data taken from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey and refer to adults aged 18 years and older.

* Data taken from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey and refer to adults aged 18 years and older.

Transgender Individuals

Limited information exists on cigarette smoking prevalence among transgender people; however, cigarette smoking prevalence among transgender adults is reported to be higher than among the general population of adults.3

The transgender population is considered especially vulnerable because of high rates of substance abuse, depression, HIV infection, and social and employment discrimination, all of which are associated with higher smoking prevalence.4

- Gay men have high rates of HPV infection which, when coupled with tobacco use, increases their risk for anal and other cancers.5

- LGBT individuals often have risk factors for smoking that include daily stress related to prejudice and stigma that they may face.6,7

- Bartenders and servers in LGBT nightclubs are exposed to high levels of secondhand smoke.8

- Among women, secondhand smoke exposure is more common among non-smoking lesbian women than among non-smoking straight women.9

- LGB individuals are 5 times more likely than others to never intend to call a smoking cessation quitline.10

- LGBT individuals are less likely to have health insurance than straight individuals,11 which may negatively affect health as well as access to cessation treatments, including counseling and medication.

- Gay, bisexual, and transgender men are 20% less likely than straight men to be aware of smoking quitlines despite LGBT individuals having exposure to tobacco cessation advertising similar to straight individuals’ exposure.12

High rates of tobacco use within the LGBT community are due in part to the aggressive marketing by tobacco companies that sponsor events, bar promotions, giveaways, and advertisements.4,5,13

- Tobacco companies advertise at “gay pride” festivals and other LGBT community events and contribute to local and national LGBT and HIV/AIDS organizations.5

- Tobacco advertisements in gay and lesbian publications often depict tobacco use as a “normal” part of LGBT life.4

- The tobacco industry encourages menthol cigarette use among LGBT populations.13

- Approximately 36% of LGBT smokers report smoking menthol cigarettes compared to 29% of heterosexual/straight smokers.13

- The marketing campaign, Project SCUM (Sub-Culture Urban Marketing), was created in the mid-1990s by a tobacco company to target LGBT and homeless populations.14

Culturally appropriate anti-smoking health marketing strategies and mass media campaigns like CDC’s Tips From Former Smokers national tobacco education campaign, as well as CDC-recommended tobacco prevention and control programs and policies, can help reduce the burden of disease among the LGBT population.

- T, Scout, Kim Y, Fagan P, Vera LE, Emery S. Transgender Use of Cigarettes, Cigars, and E-cigarettes in a National Studyexternal icon. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2017;53(1):e1-e7 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- American Lung Association. The LGBT Community: A Priority Population for Tobacco Control pdf icon[PDF–367 KB]external icon. Greenwood Village (CO): American Lung Association, Smokefree Communities Project [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Margolies L. The Same, Only Scarier—The LGBT Cancer Experienceexternal icon. American Cancer Society, 2015 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2014;63(47):1108-12 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- King BA, Dube SR, Tyan M. Current Tobacco Use Among Adults in the United States. Findings from the National Adult Tobacco Surveyexternal icon. American Journal of Public Health 2012;102(11):e93-e100 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Americans for Nonsmokers’ Rights. LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender)external icon. [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Cochran SD, Bandiera FC, Mays VM. Sexual Orientation-Related Differences in Tobacco Use and Secondhand Smoke Exposure among US Adults Aged 20-59 Years: 2003-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveysexternal icon. American Journal of Public Health 2013;103(10):1837-44 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Burns EK, Deaton EA, Levinson AH. Rates and Reasons: Disparities in Low Intentions to Use a State Smoking Cessation Quitlineexternal icon. American Journal of Health Promotion, 2011; 25, No. sp5:S59-65 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Kates J, Ranji U, Beamesderfer A, Salganicoff A, Dawson L. Health and Access to Care and Coverage for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Individuals in the U.S.external icon The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 2015; Issue Brief [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

- Fallin A, Lee YO, Bennett K, Goodin A. Smoking Cessation Awareness and Utilization Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adults: An Analysis of the 2009-2010 National Adult Tobacco Survey. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 2015:1-5 [cited 2018 Jun 1].

- Fallin A, Goodin AJ, King BA. Menthol Cigarette Smoking among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2015;48(1):93-7 [cited 2018 Jun 1].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices User Guide: Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control pdf icon[PDF–5.05 MB]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2015 [accessed 2018 Jun 1].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.

![MPOWERED: Best and Promising Practices for LGBT Tobacco Prevention and Control [PDF–2.03 MB]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20201220002729im_/https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/lgbt/images/mpowered.jpg)