Tobacco Use and Quitting Among Individuals With Behavioral Health Conditions

Adults with mental health or substance use disorders (i.e., behavioral health conditions), smoke cigarettes more than adults without these disorders.1,2,3 Mental disorders are conditions that affect a person’s thinking, feeling, mood or behavior, such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Substance use disorders occur when frequent or repeated use of alcohol, drugs, or both causes significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home.4

Approximately 1 in 4 adults in the U.S. has some form of behavioral health condition, and these adults consume almost 40% of all cigarettes smoked by adults.3

[Information described below uses data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, with different specific definitions on mental illness and substance use disorder]

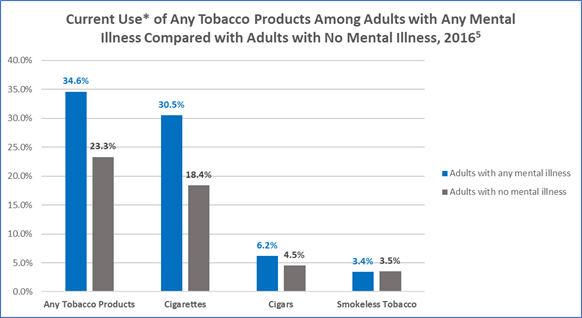

34.6% of adults with any mental illness reported current use* of tobacco in 2016 compared to 23.3% of adults with no mental illness.5

Individuals who have mood disorders, psychoses, anxiety disorders, developmental disorders, and substance use disorders are more likely to be addicted to nicotine than those without these disorders. Nicotine dependence has proven to be particularly challenging for individuals suffering from psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia.6 Smoking prevalence was highest among those with schizophrenia, at nearly 90%.6

*“Current Use” is defined as self-reported consumption of cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco in the past month (at the time of survey).

**Any Tobacco Products includes cigarettes, smokeless tobacco (i.e., snuff, dip, chewing tobacco, or “snus”), cigars, and pipe tobacco.

†Data taken from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2016, and refer to adults aged 18 years and older self-reporting any mental illness in the past year, excluding serious mental illness.

In 2016, 43.5% of adults who smoke cigarettes reported binge drinking in the past month compared to 21.7% of adults who don’t smoke.5

| Adults Who Smoke | Adults Who Don’t Smoke | |

|---|---|---|

| Current illicit drug use (in past month) | 25.3% | 7.1% |

| Marijuana | 21.8% | 5.9% |

| Cocaine | 2.5% | 0.3% |

| Heroin | 0.8% | 0.0% |

| Hallucinogens | 1.5% | 0.3% |

| Inhalants | 0.4% | 0.1% |

| Non-medical use of prescription drugs | 5.9% | 1.5% |

| Current alcohol use (in past month) | 63.5% | 52.8% |

| Binge drinking§ | 43.5% | 21.7% |

| Heavy drinking¶ | 14.6% | 4.5% |

‡ Data taken from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2016, and refer to persons aged 18 years and older reporting smoking, drug, and/or alcohol use in the past 30 days.

§ Binge alcohol use in males is defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days. Binge alcohol use in females is defined as drinking four or more drinks on an occasion.

¶ Heavy alcohol use is defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days; all heavy alcohol users are also binge alcohol users.

- People with behavioral health conditions die about 5 years earlier than those without these disorders;7 many of these deaths are caused by smoking cigarettes.7,8 Additionally, individuals with serious mental health disorders who smoke die almost 15 years earlier than individuals without these disorders who do not smoke.9

- The most common causes of death among people with behavioral health conditions are heart disease, cancer, and lung disease, which can all be caused by smoking.7

- People with behavioral health conditions who smoke cigarettes are four times more likely to die prematurely than those who do not smoke.10

- Nicotine has mood-altering effects that can temporarily mask the negative symptoms of mental health disorders, putting people with such disorders at higher risk for cigarette use and nicotine addiction.2,8

- Tobacco smoke can interact with and inhibit the effectiveness of certain medications taken by patients with behavioral health conditions, often resulting in the need for higher medication doses to achieve the same therapeutic benefit.11,12

- Many individuals with behavioral health conditions want to quit smoking but may face extra challenges in successfully quitting and thus may benefit from extra help.2,8,14

- People with mental health disorders are more likely to have stressful living conditions, have low annual household income, and lack access to health insurance, health care, and help in quitting. All these factors make it more challenging to quit.2,8

- Fewer than half of mental health and substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States offer evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments.13,15

The tobacco industry has used multiple strategies to market cigarettes to populations with behavioral health conditions. Some strategies, summarized in CDC’s Best Practices User Guide: Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control pdf icon[PDF-5.05 MB]16, include the following:

- Developing relationships with and making financial contributions to organizations that work with persons with mental health disorders.

- Funding research to foster the myth that cessation would be too stressful because persons with mental health disorders use nicotine to alleviate negative mood (i.e., self-medicate).

- Providing free or reduced-cost cigarettes to psychiatric facilities.

- Supporting efforts to block smoke-free psychiatric hospital policies.

- Creating marketing plans that target marginalized populations, including persons with mental health disorders. One example was “Project SCUM” (Sub Culture Urban Marketing), which was implemented in San Francisco in the mid-1990s.

-

Culturally appropriate anti-smoking health marketing strategies and mass media campaigns like CDC’s Tips From Former Smokers national tobacco education campaign, as well as CDC-recommended tobacco prevention and control programs and policies, can help reduce the burden of disease among people with mental illness.

A number of policy strategies can be used in mental health and substance use disorder treatment facilities to encourage smoking cessation:

- Tobacco-free campus policies that prohibit all forms of tobacco product use can support tobacco cessation, reinforce tobacco-free norms, and eliminate exposure to secondhand tobacco product emissions.13

- Counselors can ask clients who smoke cigarettes or use other tobacco products about their interest in quitting while in treatment for substance use disorders.7,11

- Evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment can help patients succeed in quitting, including cessation counseling and FDA-approved medications. Individuals with behavioral health conditions may need more intensive or longer-term treatment and support.8,16

- Staff can be prohibited from smoking with and providing cigarettes to patients as an incentive or reward.2,11

Publications

- What We Know: Tobacco Use and Quitting Among Individuals With Behavioral Health Conditions

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration—list of additional resources pdf icon[PDF–247 KB]external icon

- National Behavioral Health Network for Tobacco and Cancer Controlexternal icon

- Smoking Cessation Leadership Centerexternal icon

- Million Hearts in Municipalities: Tobacco Cessation in a Mental Health Clinic in Albany County, New York pdf icon[PDF – 128 KB]external icon

- National Partnership on Behavioral Health and Tobacco Useexternal icon (hosted on SCLC site, which also has a link to multiple resources.)

- SAMHSA Tool Kit: Implementing Tobacco Cessation Programs in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Settings: A Quick Guide for Program Directors and Clinicians external icon

- Lipari R, Van Horn S. Smoking and Mental Illness Among Adults in the United Statesexternal icon. The CBHSQ Report: March 30, 2017. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years With Mental Illness—United States, 2009–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2013;62(05):81-7 [accessed 2018 Jun 20].

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH Report Data Spotlight: Adults with Mental Illness or Substance Use Disorder Account for 40 Percent of All Cigarettes Smoked pdf icon[PDF–563 KB]external icon. U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services, Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, March 30, 2013 [accessed 2018 Oct 3].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Learn About Mental Health.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. pdf icon[PDF–35 MB]external icon Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2017 [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- NIH State‐of‐the‐Science Panel. National Institutes of Health State‐of‐the‐Science conference statement: tobacco use: prevention, cessation, and controlexternal icon. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:839‐844

- Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding Excess Mortality in Persons With Mental Illness: 17-Year Follow Up of a Nationally Representative US Survey. Medical Care 2011;49(6):599–604 [cited 2018 Jun 18].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs Fact Sheet: Adult Smoking Focusing on People With Mental Illness, February 2013. National Center for Chronic Disease and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2013 [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- Tam J, Warner KE, Meza R. Smoking and the reduced life expectancy of individuals with serious mental illness.external icon American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016; 51(6):958–966.

- Smoking Cessation Leadership Center. Fact Sheet: The Tobacco Epidemic Among People With Behavioral Health Disordersexternal icon. San Francisco: Smoking Cessation Leadership Center, University of California, 2015 [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- Smoking Cessation Leadership Center. Fact Sheet: Drug Interactions With Tobacco Smokeexternal icon. San Francisco: Smoking Cessation Leadership Center, University of California, 2015 [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- Prochaska JJ. Smoking and Mental Illness—Breaking the Linkexternal icon. New England Journal of Medicine, 2011;365:196-8 [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- Marynak K, Vanfrank B, Tetlow S, et al. Tobacco Cessation Interventions and Smoke-Free Policies in Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities—United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2018;67(18):519-23 [accessed 2018 Jul 17].

- Richter KP, Arnsten JH. A rationale and model for addressing tobacco dependence in substance abuse treatmentexternal icon. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2006;1(1):23.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The N-SSATS Report: Tobacco Cessation Servicesexternal icon. September 19, 2013. Rockville, MD [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices User Guide: Health Equity in Tobacco Prevention and Control. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2015 [accessed 2018 Jun 18].

For Further Information

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Office on Smoking and Health

E-mail: tobaccoinfo@cdc.gov

Phone: 1-800-CDC-INFO

Media Inquiries: Contact CDC’s Office on Smoking and Health press line at 770-488-5493.