Recently, I posted on this blog a piece about the use of “spectral evidence” during the Salem witch trials, in which I mentioned that 19 people died by hanging, and one person died from being crushed to death. The victim of this latter cause of death was a farmer named Giles Corey. Corey, an 81-year-old man who lived in the southwest corner of Salem village, stood accused of witchcraft, and rather than plead guilty or innocent to the charges as other members of his community had done, he resolved to stand mute in the face of the accusations. This led the court to apply of a coercive measure known as peine forte et dure, an old and fearsome practice that entailed pressing the accused with weights until he or she agrees to enter a plea.

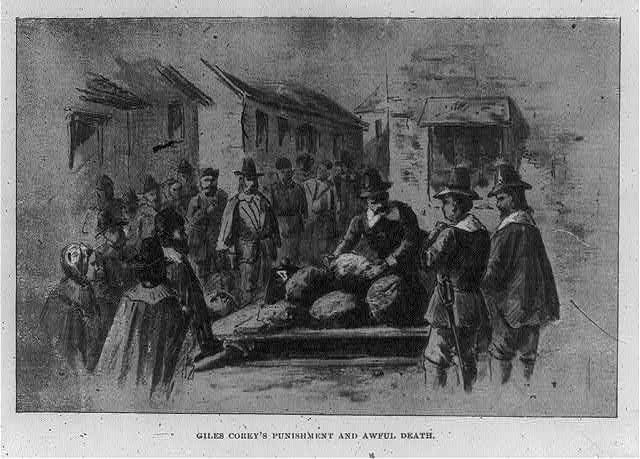

An illustration of Giles Corey’s crushing death. [Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division]

“That notorious Felons, which openly be of evil name, and will not put themselves in Enquests of Felonies that Men shall charge them with before the Justices at the King’s suit, shall have strong and hard Imprisonment (prisone forte et dure), as they which refuse to stand to the common Law of the Land.” This translation is from The Second Part of the Institutes of England by Sir Edward Coke’s (2 Inst. 178).

The statute relates to the jurisdiction of the court over persons accused of felonies. From the early 13th century, the court required the accused to seek its jurisdiction over a matter voluntarily before it could hear the case. The accused expressed this request by entering a plea. If the accused refused to enter a plea, however, the court would not hear the case, which created a very inconvenient impasse for the administration of justice (Pollock, v. 2, p. 650). The statute’s provision authorized a workaround, whereby the court could apply coercive pressure to force certain accused (notorious felons) into accepting the court’s jurisdiction.

The language in the Statute of Westminster, however, refers to prisone forte et dure, rather than peine forte et dure – a strong and hard imprisonment as opposed to a strong a hard punishment. Authorities have often interpreted the reference to prisone, that is “prison,” as imprisonment under conditions of particular hardship, sufficient hardship that it might lead to death. In similar contexts, other 13th century sources likewise omit to mention pressing the accused with weights (Holdsworth, p. 153).

It is unclear precisely when courts began to order that people who refused to enter a plea be pressed under heavy weights. Bartholomew Cotton, the author of the 13th century Historia Anglicana, recorded an instance that was supposed to have taken place in 1293 in which a great number of irons were piled on the arms and legs of an accused (Luard, ed., p. 227-8). An unambiguous instance of pressing to death finally appears in 1406. That year, the Yearbook of Henry IV records a case in which two men who had been indicted for murder stood mute rather than entering a plea. In the course of the Yearbook’s discussion, it becomes apparent both that pressing the accused under weights was not at that time a novel procedure; and that the court acknowledged that pressing the accused would certainly lead to death rather than a plea (Mich. 8 Hen. 4 plac. 2, fol. 1b-2b). This is a translation of the instructions that the court gave to the marshal:

“that the marshal should put them in low and dark chambers, naked except about the waist; that he should place upon them as much weight of iron as they could bear, and more, so that they should be unable to rise; that they should have nothing to eat but the worst bread that could be found, and nothing to drink but water taken from the nearest place to the gaol, except running water; that the clay on which they had bread they should not have water… and that they should lie there till they were dead” (Knight, V. 4, p. 356).

But why would anyone voluntarily expose oneself to this terrible fate if they could just enter a plea and avoid it? The reason was generally property. In England, following an act of King Edward II from 1324 (17 Edward 2. c.16) (though possibly earlier) and until the late 19th century, conviction of a felony resulted in the forfeiture of all of one’s property (4 William Blackstone, Commentaries 97). The penalty of forfeiture continued until it was abolished in England with the passing of the Forfeiture Act of 1870. For much of that time, the threat of forfeiture created a significant motive to avoid submitting oneself to the judgment of the court. Even the prospect of death by pressing could be preferable to leaving one’s widow and children without means.

Some historians have said that this was the motive that led Giles Corey to accept the fate that he suffered, although this idea has been challenged (Brown 1993, p. 88). Corey owned land in the Salem area, which he deeded to his sons-in-law William Cleeves and John Moulton while he was in prison. During the witchcraft trials, George Corwin, the sherriff of Essex County, seized property of some of the people who had been accused and convicted of witchcraft. Thomas Hutchinson, who was governor of Massachusetts in the 1770s, asserted in the The History of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts-Bay that the Laws and Liberties of Massachusetts which governed the colony since 1648 did not impose attainder on the property of convicted felons (Brown 1993, p. 88). This has led to an impression that Corwin’s confiscation of property was altogether illegal. The situation, however, was not so clear-cut. The Court of Oyer and Terminer, which conducted the proceedings in Salem, was operating under a new colonial regime whose establishment had cast doubt on the applicability of earlier Massachusetts law. For several months during 1692, the colony adopted a new legal order. Rather than relying on existing rules of Massachusetts criminal procedure, the new colonial governor, William Phips, charged the court with applying the laws and customs of England. It was arguably under these rules that Corwin believed seizing property was justified, but this cannot account for all of his conduct (Brown 1993, p. 88-89).

Giles Corey was charged with witchcraft on April 18, 1692. His arrest came amid suspicions that he himself aroused after he mysteriously offered testimony against his wife, Martha, and then attempted to recant. Martha had been charged with witchcraft on March 19, and the two were in prison together in Ipswich, Massachusetts, from the time of Corey’s examination until his trial on September 17 of that year. On the day of the trial, Corey entered an innocent plea as regards the indictment, but refused to submit himself to trial by the court, arguing that the court had already made up its mind about his guilt. The people, he claimed, who offered testimony against him were the same people upon whose testimony the court had relied for convictions in many previous trials. The trial was a farce (Brown 1985, p. 285). A principal piece of evidence against Corey, for instance, came from twelve-year-old Ann Putnam who claimed in her deposition on September 9 that the specter of Giles Corey appeared to her and asked her to write in his diabolical book. Faced with Corey’s refusal to cooperate, the court applied the peine forte et dure.

Corey was pressed to death by Captain John Gardner of Nantucket in an empty field on Howard Street, which was next to the jail in Salem Village, between September 17 and 19, 1692 (Brown 1985, p. 290). Peine forte et dure was abolished in England in 1772, during the reign of King George III (12 Geo. 3, c. 20).

References:

Brown, David C. “The Forfeitures at Salem, 1692.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Jan., 1993, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 85-111.

Brown, David C. “The Case of Giles Cory,” Essex Institute Historical Collections. Vol. 121, No. 1985: 282-299.

Craker, Wendel D. “Spectral Evidence, Non-Spectral Acts of Witchcraft, and Confession at Salem in 1692.” The Historical Journal, Vol. 40, No. 2 (June 1997), pp. 331-358.

Holdsworth, William Searle, Sir (1871-1944). A History of English Law. London, Methuen & co., 1903-.

Knight, Charles. The English Cyclopaedia. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1854-1872, 25 v.