14.3. The Development Phase

14.3.1. Step Four – Requirement Definition

14.3.1.1. Conduct Performance Risk Analysis

14.3.1.2. Conduct a Requirements Analysis

14.3.1.3. Build Requirements Roadmap

14.3.1.3.1. Automated Requirements Roadmap Tool

14.3.1.3.2. Acceptable Quality Levels (AQLs)

14.3.1.3.3. Performance Assessment Strategies

14.3.1.3.4. Performance Assessment Personnel

14.3.1.3.5. Assessment Methods

14.3.1.3.6. Contractor’s Quality Control Plan

14.3.1.3.7. Create Your Performance Reporting Structure

14.3.1.4. Standardize Requirements Where Possible to Leverage Market Influence

14.3.1.5. Develop a Performance Work Statement (PWS) and Statement of Objectives (SOO)

14.3.1.5.1. Format

14.3.1.5.2. Best Practices and Lessons Learned for Developing PWS

14.3.1.5.3. Style Guidelines for Writing PWS

14.3.1.5.4. Reviewing your PWS

14.3.1.6. Develop Quality Assessment Surveillance Plan (QASP) Outline

14.3.1.7. Develop Independent Government Estimate (IGE) Based on Projected Demand Forecast

14.3.1.8. Establish Stakeholder Consensus

14.3. The Development Phase

At this point of the process, the Planning Phase of the seven step service acquisition process has been completed. The acquisition team is now ready to use the collected data from the previous three steps (Form the Team, Current Strategy and Market Research) to begin developing the Requirements Document (Step 4) and the Acquisition Strategy (Step 5).

Figure 14.3.1.F1. Model of Step Four

14.3.1. Step Four – Requirement Definition

14.3.1.1. Conduct Performance Risk Analysis

As part of the requirements development process you must identify and analyze risk areas that can impact the performance results you are trying to achieve. Identify possible events that can reasonably be predicted which may threaten your acquisition. Risk is a measure of future uncertainties in achieving successful program performance goals. Risk can be associated with all aspects of your requirement. Risk addresses the potential variation from the planned approach and its expected outcome. Risk assessment consists of two components: (1) probability (or likelihood) of that risk occurring in the future and (2) the consequence (or impact) of that future occurrence.

Risk analysis includes all risk events and their relationships to each other. Therefore, risk management requires a top-level assessment of the impact on your requirement when all risk events are considered, including those at the lower levels. Risk assessment should be the roll-up of all low-level events; however, most likely, it is a subjective evaluation of the known risks, based on the judgment and experience of the team. Therefore, any roll-up of requirements risks must be carefully done to prevent key risk issues from “slipping through the cracks.”

It is difficult, and probably impossible, to assess every potential area and process. The program or project office should focus on the critical areas that could impact your program and thus impact your performance results. Risk events may be determined by examining each required performance element and process in terms of sources or areas of risk. Broadly speaking, these areas generally can be grouped as cost, schedule, and performance, with the latter including technical risk. When the word “system” is used, it refers to the requirement for services as a “system” with many different activities and events. The more complex the service requirement is, the more likely it will have the components and characteristics of a “system.” The following are some typical risk areas:

- Business/Programmatic Risk

- Scheduling issues that may impact success?

- Technical Risk

- Maturity of technology and processes reliant on technology

- Funding Risk

- Are funds identified for which availability is reliant on pending events or approvals? Have adequate funds been identified?

- Process Risk

- Are new processes required to be implemented?

- Will the best contractors have time to propose?

- Organizational Risk

- Implementing change within an organization

- Risk Summary

- Overview of the risk associated with implementing the initiative e.g. “Is there adequate service life remaining to justify this change?”

Additional areas, such as environmental impact, security, safety, and occupational health are also analyzed during the requirements definition phase. The acquisition team should consider these areas for early assessment since failure to do so could cause significant consequences. Program/project managers must recognize that any work being performed on government property or government workspace should have the proper control and oversight into access of facilities, clearances, and visitor control.

Identifying risk areas requires the acquisition team to consider relationships among all these risks and may identify potential areas of concern that would have otherwise been overlooked. This is a continuous process that examines each identified risk (which may change as circumstances change), isolate the cause, determine the effects, and then determine the appropriate risk mitigation plan. If your acquisition team is requesting the contractor to provide a solution as part of their proposal that contains a performance-based statement of work and performance metrics and measures, then it is also appropriate to have the contractor provide a risk mitigation plan that is aligned with that solution.

To learn more about risk management and using a risk mitigation plan, we suggest you take the DAU online course, entitled Continuous Learning Module (CLM) 017, Risk Management. Figure 14.3.1.1.F1 is a typical risk analysis model.

Figure 14.3.1.1.F1. Risk Analysis Model

14.3.1.2. Conduct a Requirements Analysis

Like risk analysis, requirements analysis means conducting a systematic review of your requirement given the guidance you captured from your stakeholders during the planning phase – steps One, Two, and Three. The objective of this step is to describe the work in terms of required results rather than either “how” the work is to be accomplished or the number of hours to be provided (FAR 37.602). This analysis is the basis for establishing the high level objectives, developing performance tasks, and standards, writing the Performance Work Statement, and producing the Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan.

The acquisition team needs to identify the essential processes, and outputs or results required. One approach is to use the "so what?" test during this analysis. For example, once the analysis identifies the outputs, the acquisition team should verify the continued need for the output. The team should ask questions like the following:

- Who needs the output or result?

- Why is the output needed?

- What is done with it?

- What occurs as a result?

- Is it worth the effort and cost?

- Would a different output be preferable?

- And so on...

14.3.1.3. Build Requirements Roadmap

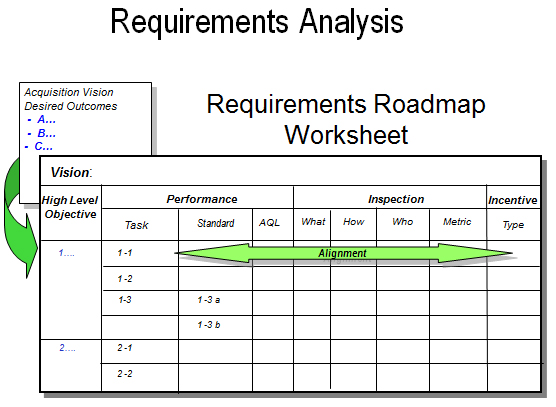

The requirements roadmap worksheet (Appendix A) provides a method that links required performance to the overall acquisition desired outcomes. The roadmap takes the performance tasks and aligns performance standards and acceptable quality levels (AQLs). It also includes detailed inspection information and responsibilities. Each of these areas will be discussed in greater detail in this step. When using this approach, it is vital that all elements of the document be aligned with the mission objectives you are trying to deliver. If you develop a performance task and standard, but have no way to inspect it, you have a problem. In this case you will need to revisit the objective or find new technology for the inspection. All the elements must fit together as a whole before writing the PWS.

As you build your roadmap with high level objectives and task statements, prioritize them in descending order of importance based on risk, criticality or priority. This will help you later when determining what you want to evaluate in a contractors proposal.

Figure 14.3.1.3.F1. Requirements Roadmap Worksheet

Initially, the High Level Objectives (HLO) need to be defined. What must be accomplished to satisfy the requirement? This should have been accomplished during steps 1 and 2 when you were talking with your stakeholders and customers. To define HLOs, list what needs to be accomplished to satisfy the overall requirement, from a top-level perspective. HLOs are similar to level two in work bread down structures.

Tasks are the results or actions required to achieve the HLO. It may take several tasks to satisfy a HLO. Tasks consist of results, the context of what or who the results pertain to and what actions are required to complete the task. Defining the task goes into greater detail and expands the stakeholder analysis beyond the top-level perspective. The goal of a task is to adequately describe what action or result is required (not how to accomplish it).

Tasks are generally nouns and verbs and tend to be declarative statements such as the following:

- Conduct a study on …

- Provide financial analysis of…

- Maintain vehicles…

- Review and assess…

- Develop a strategic plan…

- Identify potential…

- Perform and document…

When developing tasks ask the question “WHY is this action needed?” A ”because” answer usually drives the focus on the performance results needed. “Why do you want the river to be dredged?” “Because we want the boats to be able to go in and out.” Bottom line: we need to keep the river navigable. That is the objective.

Next, identify appropriate and reasonable performance standards (i.e., how well the work must be performed to successfully support mission requirements). The purpose is to establish measurable standards (adjectives and adverbs) for each of the tasks that have been identified. The focus is on adjectives and adverbs that describe the desired quality of the service’s outcome. How fast, how thorough, how complete, how error free, etc. Examples of performance standards could include the following:

- Response times, delivery times, timeliness (meeting deadlines or due dates), and adherence to schedules.

- Error rates or the number of mistakes or errors allowed in meeting the performance standard.

- Accuracy rates.

- Milestone completion rates (the percent of a milestone completed at a given date).

- Cost control (performing within the estimated cost or target cost), as applied to flexibly priced contracts.

This should reflect the minimum needs to meet the task results. The standards you set are cost drivers because they describe the performance levels that the contractor must reach to satisfy the task. Therefore, they should accurately reflect what is needed and should not be overstated. In the case of keeping a river navigable, the standard might be: “100 feet wide, 12 feet deep at mean low water.” Thus we have a measure for what we define as ”navigable.”

Standards should accurately reflect what is needed and should not be overstated. We should ask the following questions in this area:

- Is this level of performance necessary?

- What is the risk to the government if it does not have this level of performance?

- What is the minimum acceptable level of performance necessary to successfully support your mission?

In the case of the navigable river, 12 feet deep means low water might be sufficient for pleasure craft type usage. However, setting a depth of 34 feet which might be needed for larger commercial watercraft that may never use that river would be considered overkill and a waste of money. The standard must fit, or be appropriate to, the outcome’s need.

Another way of describing a performance standard is using terms like measurement threshold or defining it as “the limit that establishes that point at which successful performance has been accomplished.” Performance standards should:

- Address quantity, quality and timeliness;

- Be objective, not subjective (if possible);

- Be clear and understandable;

- Be realistically achievable;

- Be true indicators of outcome or output; and

- Reflect the government’s needs.

The performance standards should describe the outcome or output measures but does not give specific procedures or instructions on how to produce them. When the government specifies the “how-to’s,” the government also assumes responsibility for ensuring that the design or procedure will successfully deliver the desired result. On the other hand, if the government specifies only the performance outcome and accompanying quality standards, the contractor must then use its best judgment in determining how to achieve that level of performance. Remember that a key PBA tenet is that the contractor will be entrusted to meet the government’s requirements and will be handed both the batons of responsibility and authority to decide how to best meet the government’s needs. The government’s job is to then to evaluate the contractor’s performance against the standards set forth in the PWS. Those assessment methods identified in the QASP, together with the contractor’s quality control plan, will also help in evaluating the success with which the contractor delivers the contracted level of performance.

14.3.1.3.1. Automated Requirements Roadmap Tool

The Automated Requirements Roadmap Tool (ARRT) is a job assistance tool that enables users to develop and organize performance requirements into draft versions of the performance work statement (PWS), the quality assurance surveillance plan (QASP), and the performance requirements summary (PRS). ARRT provides a standard template for these documents and some default text that can be modified to suit the needs of a particular contract. This tool should be used to prepare contract documents for all performance-based acquisitions for services. The ARRT is available for download at: http://sam.dau.mil/ARRTRegistration.aspx

14.3.1.3.2. Acceptable Quality Levels (AQLs)

The acquisition team may also establish an AQL for the task, if appropriate. The AQL is a recognition that unacceptable work can happen, and that in most cases zero tolerance is prohibitively expensive. In general, the AQL is the minimum number (or percentage) of acceptable outcomes that the government will permit. An AQL is a deviation from a standard. For example, in a requirement for taxi services, the performance standard might be "pickup the passenger within five minutes of an agreed upon time." The AQL then might be 95 percent; i.e., the taxi must pick up the passenger within five minutes 95 percent of the time. Failure to perform at or above the 95 percent level could result in a contract price reduction or other action. AQLs might not be applicable for all standards especially for some services such as Advisory and Assistance Services (A&AS) or research and development (R&D) services.

Once the team has established the AQLs, they should review them:

- Are the AQLs realistic?

- Do they represent true minimum levels of acceptable performance?

- Are they consistent with the selected method of surveillance?

- Are they aligned with the task and standard?

- Is the AQL clearly understood and communicated?

14.3.1.3.3. Performance Assessment Strategies

Traditional acquisition methods have used the term “quality assurance” to refer to the functions performed by the government to determine whether a contractor has met the contract performance standards. The QASP is the government’s surveillance document used to validate that the contractor has met the standards for each performance task.

The QASP describes how government personnel will evaluate and assess contractor performance. It is intended to be a “living” document that should be revised or modified as circumstances warrant. It’s based on the premise that the contractor, not the government, is responsible for delivering quality performance that meets the contract performance standards. The level of performance assessment should be based on the criticality of the service or associated risk and on the resources available to accomplish the assessment.

Performance assessment answers the basic question “How are you going to know if it is good when you get it?” Your methods and types of assessment should focus on how you will approach the oversight of the contractor’s actual performance and if they are meeting the standards that are set in the PWS. Completing the assessment elements of the requirements roadmap will ensure that you determine who and how you will assess each performance task before you write the PWS. If you develop a task or standard that cannot be assessed you should go back and reconsider or redefine the task or standard into one that can be assessed. This section of the roadmap provides the foundation for your QASP. The QASP is not incorporated into the contract since this enables the government to make adjustments in the method and frequency of inspections without disturbing the contract. An informational copy of the QASP should be furnished to the contractor.

14.3.1.3.4. Performance Assessment Personnel

The COR plays an essential role in the service acquisition process and should be a key member of your acquisition team. During the requirements development process his/her input is vital, because they will be living with this requirement during performance. In accordance with DFARS 201.602-2, “A COR must be qualified by training and experience commensurate with the responsibilities to be delegated in accordance with department/agency guidelines.”

The method for assessing the contractor’s performance must be addressed before the contract is awarded. It is the responsibility of the COR, as part of the acquisition team, to assist in developing performance requirements and quality levels/standards, because the COR will be the one responsible for conducting that oversight. The number of assessment criteria and requirements will vary widely depending on the task and standard as it relates to the performance risk involved, and the type of contract selected. Using the requirements roadmap worksheet (Appendix A) will help ensure that the requirement and assessment strategies are aligned.

14.3.1.3.5. Assessment Methods

Several methods can be used to assess contractor performance. Performance tasks with the most risk or mission criticality warrant a higher level of assessment than other areas. No matter which method you select you should periodically review your assessment strategy based on documented contractor performance and adjust as necessary. Below are some examples of commonly used assessment methods.

Random sampling: Random sampling is a statistically based method that assumes receipt of acceptable performance if a given percentage or number of scheduled assessments is found to be acceptable. The results of these assessments help determine the government’s next course of action when assessing further performance of the contractor. If performance is considered marginal or unsatisfactory, the evaluators should document the discrepancy, begin corrective action and ask the contractor why their quality control program failed. If performance is satisfactory or exceptional, they should consider adjusting the sample size or sampling frequency. Random sampling is the most appropriate method for frequently recurring tasks. It works best when the number of instances is very large and a statistically valid sample can be obtained.

Periodic sampling: Periodic sampling is similar to random sampling, but it is planned at specific intervals or dates. It may be appropriate for tasks that occur infrequently. Selecting this tool to determine a contractor’s compliance with contract requirements can be quite effective, and it allows for assessing confidence in the contractor without consuming a significant amount of time.

Trend analysis: Trend analysis should be used regularly and continually to assess the contractor’s ongoing performance over time. It is a good idea to build a database from data that have been gathered through performance assessment. Additionally, contractor-managed metrics may provide any added information needed for the analysis. This database should be created and maintained by government personnel.

Customer feedback: Customer feedback is firsthand information from the actual users of the service. It should be used to supplement other forms of evaluation and assessment, and it is especially useful for those areas that do not lend themselves to the typical forms of assessment. However, customer feedback information should be used prudently. Sometimes customer feedback is complaint-oriented, likely to be subjective in nature, and may not always relate to actual requirements of the contract. Such information requires thorough validation.

Third-party audits: The term “third-party audit” refers to contractor evaluation by a third-party organization that is independent of the government and the contractor. All documentation supplied to, and produced by, the third party should be made available to both the government and the contractor. Remember, the QASP should also describe how performance information is to be captured and documented. This will later serve as past performance information. Effective use of the QASP, in conjunction with the contractor’s quality control plan, will allow the government to evaluate the contractor’s success in meeting the specified contract requirements. Those assessment methods identified in the QASP, together with the contractor’s quality control plan will help evaluate the success with which the contractor delivers the level of performance agreed to in the contract.

In our case of the navigable river, the method of inspection might be using a boat with sonar and GPS, thus measuring the channel depth and width from bridge A to Z. The results would document actual depths and identify where any depths are not compliant with the standards.

14.3.1.3.6. Contractor’s Quality Control Plan

A quality control plan is a plan developed by the contractor for its internal use to ensure that it delivers the service levels contained in the contract. The quality control plan should be part of the contractor’s original proposal, and in many cases, it is incorporated into the resultant contract. The inspection of services clause requires that the quality control plan be acceptable to the government.

14.3.1.3.7. Create Your Performance Reporting Structure

Invest some time to determine how and to whom you will present the contractor’s performance results. Most often this is to your leadership and stakeholders. This should take the form of periodic performance reviews that quickly capture summary performance results yet also provide the drill down capability when necessary to identify and resolve performance problems. One way to structure your performance reporting is to use the key stakeholder outcomes as key performance indicators (KPIs). These measures are few in number, but supported by the process and sub-process measures in your PWS. The chart below, Figure 14.3.1.3.7.F1, illustrates this approach.

Figure 14.3.1.3.7.F1. Performance Indicators

Key Process Indicators (KPIs): Top level summary metrics that quickly capture current performance status that link to your stakeholder desired outcomes.

Process Measures: Capture the overall status of each process area contained in your PWS.

Sub Process Measures: Capture specific performance outcomes for each performance task in your PWS.

More on performance reporting will be discussed in step seven, but remember that in developing your approach make sure that the effort required for collection and measurement does not exceed the value of the information.

14.3.1.4. Standardize Requirements Where Possible to Leverage Market Influence

Market research may reveal that commercially acceptable performance standards will satisfy the customer with the potential of a lower price. The acquisition team may also discover that industry standards and tolerances are measured in different terms than those that the customer has used in the past. Rather than inventing metrics or quality or performance standards, the acquisition team should use existing commercial quality standards (identified during market research), when applicable. It is generally a best practice to use commercial standards where they exist, unless the commercial standard proves inappropriate for the particular requirement. Industry’s involvement, accomplished through public meetings, requests for information (RFI), or draft request for proposals (RFPs), will help in finding inefficiencies in the PWS, and will also lead to cost efficiencies that can be achieved through the use of commercial practices.

14.3.1.5. Develop a Performance Work Statement (PWS) and Statement of Objectives (SOO)

The PWS comprises the “heart” of any service acquisition and the success or failure of a contract is greatly dependent on the quality of the PWS. Ensure you have completed all elements of the requirements roadmap worksheet including inspection before starting to write the PWS. There is no mandatory template or outline for a PWS. The FAR only requires that agencies to the maximum extent practicable:

- Describe work in terms of required results rather than “how” the work is to be accomplished or the number of hours to be provided.

- Enable assessment of work performance against measurable performance standards.

- Rely on measurable performance standards and financial incentives in a competitive environment to encourage innovation and cost effective methods of performing the work.

The roadmap worksheet contains the basic outline for the requirements section of your PWS. The HLOs and supporting performance tasks and standards should be the main component of your PWS. After the introduction and general sections, the nuts and bolts of your PWS might have the HLOs listed as 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, as appropriate. Under HLO 3.1, you would list the tasks and standards associated with this HLO. For example, 3.1.1 would be task 1 under that HLO 3.1. A task can have multiple performance standards and AQLs associated with it from your roadmap such as timeliness, quality etc. Make sure they are accurately captured in your PWS.

14.3.1.5.1. Format

There is no mandatory format for a PWS; however, one normally includes the following:

1. Introduction: It should capture the importance of your mission and how this requirement contributes to the overall mission of your organization. The introduction describes your overall acquisition vision and desired mission results. It sets your expectations of contractor performance in terms of teamwork and improving mission results thru efficiencies and process improvements. Keep this section focused and relatively brief, but capture the importance of achieving mission results and your performance expectations.

2. Background: This section briefly describes the scope of the performance requirement and the desired outcome. Provide a brief historical description of the program/requirement that provides the context for this effort (include who is being supported and where). Describe the general desired outcomes of your new requirement. Consider that a contractor will have a greater chance at success with adequate information that clearly defines the magnitude, quality, and scope of the desired outcomes.

3. General Requirements: Describe general requirements that are not specifically related to performance outcomes but have an impact on the success of the mission. (Place of performance, period of performance, security clearance requirements, etc.)

4. Performance Requirements: This portion is basically transference of the HLOs, tasks and standards from the roadmap into the PWS. Specify standards to which the task must be completed. Your major paragraphs and subparagraphs should be in descending order of importance based on your earlier risk analysis.

5. Deliverables: This section contains information on deliverables such as data requirements, reports or any other items contained within a contract data requirements list (CDRL). Some agencies list CDRL items separately in Section J of the contract. Limit CDRL requirements to those needed by the government to make a decision, measure performance, or to comply with a higher level requirement. The inspection portion of your roadmap identifies ‘what’ is going to be inspected, and this often results in a data deliverable.

6. Special Requirements: This section will include information on Government Furnished Property (GFP) or Equipment (GFE). Also include any special security or safety information, environmental requirements, special work hours and contingency requirements. If necessary, include a transition plan and a listing of all applicable documents and/or directives. The number of directives referenced should be limited to those required for this specific effort such as quality standards, statutory, or regulatory.

7. Task Orders: If task orders will be used, you need to address their use and ensure each task order has a well-written PWS that includes HLOs, tasks, standards, data deliverables and incentives as appropriate. Task descriptions should clearly define each deliverable outcome. Subtasks should be listed in their appropriate order and should conform to the numbering within the basic PWS from which the task order derives. All task orders must capture performance assessments gathered using the task order QASP. Each task order should have a trained COR assigned.

However, the team can adapt this outline as appropriate. Before completing the PWS, there should be final reviews, so be sure your team examines every performance requirement carefully and delete any that are not essential. Many agencies have posted examples of a PWS that can provide some guidance or helpful ideas. Because the nature of performance-based acquisition is tied to mission-unique or program-unique needs, keep in mind that another agency's solution may not be an applicable model for your requirement.

14.3.1.5.2. Best Practices and Lessons Learned for Developing PWS

Best practices and lessons learned for developing a PWS include:

- The purpose of defining your requirement at high level objectives and tasks is to encourage innovative solutions for your requirement. Don't specify the requirement so tightly that you get the same solution from each offeror. If all offerors provide the same solution, there is no creativity and innovation in the proposals.

- The acquisition team must move beyond less efficient approaches of buying services (time and material or labor hour), and challenge offerors to propose their own innovative solutions. Specifically, specifying labor categories, educational requirements, or number of hours of support required should be avoided because they are "how to" approaches. Instead, let contractors propose the best people with the best skill sets to meet the need and fit the solution. The government can then evaluate the proposals based both on the quality of the solution and the experience of the proposed personnel.

- Prescribing manpower requirements limits the ability of offerors to propose their best solutions, and it could preclude the use of qualified contractor personnel who may be well suited for performing the requirement but may be lacking -- for example – a complete college degree or the exact years of specified experience.

- Remember that how the PWS is written will either empower the private sector to craft innovative solutions, or stifle that ability.

14.3.1.5.3. Style Guidelines for Writing PWS

The most important points for writing style guidelines are summarized below:

Style: Write in a clear, concise and logical sequence. If the PWS is ambiguous, the contractor may not interpret your requirements correctly and courts are likely to side with the contractor’s interpretation of the PWS.

Sentences: Replace long, complicated sentences with two or three shorter, simpler sentences. Each sentence should be limited to a single thought or idea.

Vocabulary: Avoid using seldom-used vocabulary, legal phrases, technical jargon, and other elaborate phrases.

Paragraphs: State the main idea in the first sentence at the beginning of the paragraph so that readers can grasp it immediately. Avoid long paragraphs by breaking them up into several, shorter paragraphs.

Language Use: Use active voice rather than passive.

Abbreviations: Define abbreviations the first time they are used, and include an appendix of abbreviations for large documents.

Symbols: Avoid using symbols that have other meanings.

Use shall and don’t use will: The term shall is used to specify that a provision is binding and usually references the work required to be done by the contractor. The word “will” expresses a declaration of purpose or intent.

Be careful using any or either. These words clearly imply a choice in what needs to be done contractually. For instance, the word any means in whatever quantity or number, great or small which leaves it at the discretion of the contractor.

Don’t use and/or since the two words together (and/or) are meaningless; that is, they mean both conditions may be true, or only one may be true.

Avoid the use of etc. because the reader would not necessarily have any idea of the items that could be missing.

Ambiguity: Avoid the use of vague, indefinite, uncertain terms and words with double meanings.

Do not use catch-all/open-ended phrases or colloquialisms/jargon. Examples of unacceptable phrases include “common practice in the industry,” “as directed,” and “subject to approval.”

Terms: Do not use terms without adequately defining them.

14.3.1.5.4. Reviewing your PWS

You can review the PWS by answering the following questions:

- Does the PWS avoid specifying the number of contractor employees required to perform the work (except when absolutely necessary)?

- Does the PWS describe the outcomes (or results) rather than how to do the work?

- What constraints have you placed in the PWS that restrict the contractors ability to perform efficiently? Are they essential? Do they support your vision?

- Does the PWS avoid specifying the educational or skill level of the contract workers (except when absolutely necessary)?

- Can the contractor implement new technology to improve performance or to lower cost?

- Are commercial performance standards utilized?

- Do the performance standards address quantity, quality and timeliness?

- Are the performance standards objectives easy to measure and timely?

- Is the assessment of quality a quantitative or qualitative assessment?

- Will two different CORs come to the same conclusion about the contractor’s performance based on the performance standards in the PWS?

- Are AQLs clearly defined?

- Are the AQL levels realistic and achievable?

- Will the customer be satisfied if the AQL levels are exactly met? (Or will they only be satisfied at a higher quality level?

- Are the persons who will perform the evaluations identified?

14.3.1.6. Develop Quality Assessment Surveillance Plan (QASP) Outline

The heart of your QASP comes directly from your roadmap. It addresses each HLO and its tasks with their associated standards. It includes the methods and types of inspection (who is going to do the inspection, how the inspections are to be conducted and how often they are to be conducted). Numerous organizations use the term performance requirements summary (PRS), while others incorporate the standards within the PWS. Either way, as long as the HLOs and tasks are tied to the standards in the resultant contract, that is what is important.

Recognize that the methods and degree of performance assessment may change over time in proportion to the evaluator’s level of confidence in the contractor’s performance. Like the PWS there is no required format for a QASP, a suggested format is shown below:

- Purpose

- Roles and Responsibilities

- Performance Requirements and Assessments

- Objective, Standard, AQL, Assessment Methodology

- Assessment Rating Structure Outline (1 to 5)

- Performance Reporting - establish reporting frequency to leadership

- Metrics

- Remedies used and impacts

- CPARS Report

- Attachments

- Sample Contract Deficiency Report

- Sample Performance Report Structure

Reviewing Your QASP

You can review the QASP by answering the following questions:

- Is the value of evaluating the contractor’s performance on a certain task worth the cost of surveillance?

- Has customer feedback been incorporated into the QASP?

- Have random or periodic sampling been utilized in the QASP?

- Are there incentives to motivate the contractor to improve performance or to reduce costs?

- Are there disincentives to handle poor performance?

- Will the contractor focus on continuous improvement?

14.3.1.7. Develop Independent Government Estimate (IGE) Based on Projected Demand Forecast

Determining an accurate IGE can be a challenging task for the acquisition team. This will involve various skills sets from the team to project demand forecasts for the service. What sort of constraints do you have in computing your IGE? You could have cost constraints that can limit what you require in the PWS or Statement of Objectives (SOO). Program scope may also be an issue if it’s difficult to determine exactly what the contractor is being asked to propose. Remember, if you can’t develop an IGE, how do you expect the contractor to propose based on the PWS?

14.3.1.8. Establish Stakeholder Consensus

This is the point where it would be beneficial to revisit the customer and stakeholders to ensure everyone is satisfied with the PWS and the way forward. It is typical to have varying levels of resistance to the team’s strategy. The key is to develop an acquisition team approach to sell the strategy to the customer and stakeholders and then schedule review cycles.