2.0 Chapter Introduction

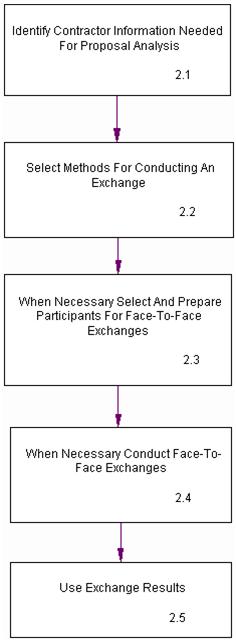

Procedural Steps. The following flow chart outlines the steps of fact-finding:

2.1 Identifying Contractor Information Needed For Proposal Analysis

Exchanges (FAR 15.306). "Exchange" is a general term used to describe any dialogue between the Government and the contractor after receipt of the proposal(s), including contract negotiations. However, the material in this chapter is limited to exchanges prior to contract negotiation.

The objective of prenegotiation exchanges is to identify and obtain available contractor information needed to complete proposal analysis. In addition, most types of prenegotiation exchanges provide the contractor with an opportunity to seek clarification of the Government's stated contract requirements.

In competitive negotiations, there may be several different types of exchanges, each with its own unique rules:

- Clarifications with the intent to award without discussions;

- Communications with contractors before establishment of the competitive range; and

- Exchanges after establishment of the competitive range but before negotiations.

In noncompetitive negotiations, exchanges after receipt of proposals and prior to negotiations are normally referred to as fact-finding.

Information Already Available. Before conducting an exchange with the contractor, you should already have:

- The solicitation, unilateral contract modification, or any other document that prompted the contractor's proposal;

- The proposal and all information submitted by the contractor to support the proposal;

- Information from your market research concerning the product, the market, cost or price trends, and any relevant acquisition history;

- Any relevant field pricing or audit analyses;

- In-house technical analyses; and

- Your initial price analysis and, where appropriate, cost analysis.

Clarifications (FAR 15.306(a), FAR 52.212-1(g), and FAR 52.215-1(f)(4))(WECO Cleaning Spec., CGEN B-279305, June 3, 1998).

Clarifications are limited exchanges, between the Government and contractors, that may occur when the Government contemplates a competitive contract award without discussions.

Remember that award may only be made without discussions when the solicitation states that the Government intends to evaluate proposals and make award without discussions. For example, both the standard FAR Instructions to Offerors -- Competitive Acquisition and Instructions to Offerors -- Commercial Items provisions advise prospective offerors that award will be made without discussions.

When you contemplate making a competitive contract award without conducting discussions, you may give one or more contractors the opportunity to clarify certain aspects of proposals that may have an effect on the award decision. For example, a request for clarification might give the contractor an opportunity to:

- Clarify the relevance of a contractor's past performance information;

- Respond to adverse past performance information if the contractor has not previously had an opportunity to respond; or

- Resolve minor or clerical errors, such as:

- Obvious misplacement of a decimal point in the proposed price;

- Obviously incorrect prompt payment discount;

- Obvious reversal of price f.o.b. destination and f.o.b. origin; or

- Obvious error in designation of the product unit.

- Resolve issues of contractor responsibility or the acceptability of the proposal as submitted.

The key word is limited. The purpose of a clarification is to permit a contractor an opportunity to clarify key points about the proposal as originally submitted. You must not give the contractor an opportunity to revise its proposal.

Communications (FAR 15.306(b)). When negotiations are anticipated, the contracting officer must first establish the competitive range. Communications are exchanges, between the Government and contractors, after receipt of proposals, leading to establishment of the competitive range. Communications are only authorized when the contractor is not clearly in or clearly out of the competitive range. Specifically, communications:

- Must be held with contractors whose past performance information is the determining factor preventing them from being placed within the competitive range. Such communications must address adverse past performance information to which the contractor has not had a prior opportunity to respond.

- May be held with other contractors whose exclusion from, or inclusion in, the competitive range is uncertain. They may be used to:

- Enhance Government understanding of the proposal;

- Allow reasonable interpretation of the proposal; or

- Facilitate the Government's evaluation process.

- Must not be held with any contractor not in one of the situations described above.

The purpose of communications is to address issues that must be explored to determine whether a proposal should be placed in the competitive range.

- Communications must address any adverse past performance information to which the contractor has not previously had an opportunity to comment.

- Communications may address:

- Ambiguities in the proposal or other concerns (e.g., perceived deficiencies, weaknesses, errors, omissions, or mistakes); and

- Information relating to relevant past performance.

- Communications must not permit the contractor to:

- Cure proposal deficiencies or material omissions;

- Materially alter the technical or cost elements of the proposal; and/or

- Otherwise revise the proposal.

Exchanges After Establishment of the Competitive Range But Before Negotiations. Exchanges after establishment of the competitive range but before negotiations should normally not be necessary. Proposals included in the competitive range should be adequate for negotiation. However, there may be situations when you need additional information to prepare reasonable negotiation objectives.

The purpose of such exchanges is to obtain additional information for proposal analysis and to eliminate misunderstandings or erroneous assumptions that could impede objective development. You must not give the contractor an opportunity to revise its proposal.

Fact-Finding (FAR 15.406-1). In a noncompetitive procurement, fact-finding may be necessary when information available is not adequate for proposal evaluation. It will most often be needed when:

- The proposal submitted by the contractor appears to be incomplete, inconsistent, ambiguous, or otherwise questionable; and

- Information available from market analysis and other sources does not provide enough additional information to complete the analysis.

The purpose of fact-finding is to obtain a clear understanding of all the contractor's proposal, Government requirements, and any alternatives proposed by the contractor. Hence, both you and contractor personnel should view fact-finding as an opportunity to exchange information and eliminate misunderstandings or erroneous assumptions that could impede the upcoming negotiation. Typically, fact-finding centers on:

- Analyzing the actual cost of performing similar tasks. This analysis should address such issues as whether:

- Cost or pricing data or information other than cost or pricing data are accurate, complete, and current;

- Historical costs are reasonable; or

- Historical information was properly considered in estimate development.

- Analyzing the assumptions and judgments related to contract cost or performance, such as:

- The reasonableness of using initial production lot direct labor hours and improvement curve analysis to estimate follow-on contract labor hours;

- Projected labor-rate increases; or

- Anticipated design, production, or delivery schedule problems.

Because the procurement is not competitive, there is a special temptation to negotiate during fact-finding. However, it is especially important for both parties to avoid that temptation. Negotiating during fact-finding causes the Government to lose in two ways:

- The negotiations may inadvertently harm the Government position because the issues are negotiated before analysis is completed.

- Once fact-finding turns into negotiation, it becomes less likely that any remaining fact-finding issues will be clarified.

2.2 Selecting Methods For Conducting An Exchange

Methods for Conducting an Exchange. The following table identifies several methods commonly used to conduct exchanges after receipt of proposals but prior to contract negotiation. The table also identifies when each method is commonly used in procurements with prices exceeding the simplified acquisition threshold.

|

Methods Commonly Used to Conduct Exchanges Prior to Contract Award

|

|

Method of Exchange

|

Use in Exchange Situations

|

|

Telephone

|

Rarely used for 2-way exchanges in competitive situations. May be used to request a written response to relatively simple questions.

Commonly used in noncompetitive situations when questions are relatively simple. Especially common when the dollar value is relatively low.

Rarely used in noncompetitive situations when questions are relatively complex.

|

|

Written

|

Commonly used in competitive situations to assure complete documentation of the information requested and received.

Rarely used in noncompetitive situations unless the question is very complex and there is time to wait for a written reply.

|

|

Face-to-face -- involving either a single representative from each side or several team members from each side. Teams may include audit and/or technical specialists

|

Rarely used for exchanges in competitive situations.

Commonly used in noncompetitive situations when questions are relatively complex and the dollar value justifies the cost involved.

|

Telephone Exchanges. Telephone exchanges permit personal and timely communications related to less complex issues. When using telephone exchanges, there are several points that you should consider.

- Identify all questions to be covered before initiating an exchange. The telephone is a casual medium of exchange that we use everyday. There is a great temptation to pick up the phone whenever we have a question. Before you do, remember that multiple conversations could confuse the contractor about the issues involved.

- Make a checklist of the points you want to cover. It is easy to get sidetracked during a telephone conversation. The checklist will help keep you on track.

- Document all information requested or received. A good record is vital, but a telephone conversation does not normally provide one.

- Generally, a written summary is the most practical approach to documenting a telephone conversation.

- Some contracting officers use audio recordings, but many people resist having a conversation taped. Never tape a conversation unless all parties to the exchange give their permission. Make sure that they give permission and that permission is recorded each time a conversation is taped.

- Request a written response for complex questions or in situations where the exact wording of the response is important. For example, the exact wording of any information received from a contractor is particularly important in a competitive situation.

Written Exchanges. Written exchanges are particularly useful in competitive situations where it is important to have complete and accurate documentation of the question asked and the exact response. There are several points that you should consider before initiating a written exchange.

- Make sure that your written document asks exactly the question you want answered. The contractor may misinterpret a poorly written question.

- Make sure that your written exchange meets time constraints. Traditionally, written exchanges take two weeks or more. With e-mail, fax, and overnight mail, a written exchange can now be almost as fast as a telephone call.

Face-to-Face Exchanges. With complex issues, face-to-face exchanges with the contractor are often desirable. Exchanges at the contractor's place of business may be particularly desirable when issues are complex and the dollar value is large. Quick access to contractor technical information and support can facilitate and expedite the exchange process.

2.3 Selecting And Preparing Participants For Face-To-Face Exchanges

Select Government Team Members. For smaller less complex contract actions, the contracting officer or contract specialist may be the only Government representative participating in face-to-face exchanges. Normally as the value and complexity of the contract action increase, the size of the Government team will also increase.

Select team members based on their expertise in the areas being considered in the exchange. The table below identifies common roles in face-to-face exchanges and potential team members to fill those roles.

|

Face-To-Face Exchange Team Selection

|

|

Team Role

|

Potential Team Member

|

|

Team leader

|

Contracting officer

Contract specialist

|

|

Technical analyst

|

Engineer

Technical specialist

Project or requirements manager

End user

Commodity specialist

Inventory manager

Transportation manager

Property manager

Logistics manager

|

|

Pricing analyst

|

Auditor

Cost/Price Analyst

|

|

Business terms analyst

|

Legal Counsel

Administrative Contracting Officer

Administration Specialist

|

|

Team Leader Preparation. The team leader is responsible for team preparation as well as team leadership during the exchange session. Team preparation includes the following responsibilities:

- Planning for the exchange session. Several key points must be considered and many require coordination with team members and the contractor:

- Location of the exchange session (i.e., Government or contractor facility);

- Timing of the exchange session;

- The exchange session agenda;

- Exchange methodology (e.g., group meeting with the contractor, small team interviews, or individual interviews);

- Exchange logistics (e.g., team member availability, travel funding when applicable, or meeting room arrangements).

- Assigning roles to team members.

- Assign analysis responsibilities based on member qualifications.

- When appropriate, some team members may be assigned specific responsibility for listening to, documenting, and analyzing contractor responses.

- Assuring that team members are generally and individually prepared for the exchange session.

- Reviewing initial team questions. This review will assure that the team leader has an opportunity to:

- Become aware of the projected areas and depth of the exchange.

- Identify any issues that may cross the boundaries of individual analyses.

- Identify any inappropriate questions for elimination or rephrasing.

- Sending initial questions to the contractor. Sending initial questions to the contractor's designated team leader prior to the exchange session will speed the exchange. Why start the session by asking questions and then waiting an extended period for the contractor's initial response? Sending initial questions before the exchange will permit faster contractor responses and the contractor will also be aware of the areas of greatest Government concern. This awareness will permit better overall contractor preparation for the exchange session.

General Team Preparation. All team members must be familiar with the rules for Government-contractor dialog during the exchange session.

- Encourage team members to DO the following:

- Use questions as a way to begin the exchange.

- Start with simple questions.

- Include questions on the rationale for estimated amounts.

- Break complex issues into simple questions.

- Continue questioning until each answer is clearly understood.

- Identify and rank discussion subjects and levels of concern.

- Be thorough and systematic rather than unstructured.

- Ask for the person who made the estimate to explain the estimate.

- Caucus with team members to review answers and, if needed, formulate another round of questions.

- Assign action items for future exchanges related to unanswered questions.

- Emphasize that team members MUST NOT DO the following:

- Negotiate contract price or requirements.

- Make Government technical or pricing recommendations.

- Answer questions that other team members ask the contractor.

- Allow the contractor to avoid direct answers.

- Discuss available funding.

Technical Analyst Preparation. Technical analyst preparation includes the following:

- Analyzing the technical proposal and marking areas of concern. Government personnel must be able to communicate effectively with contract personnel. By the time that exchanges begin, key contractor personnel will have been working with the proposal for several weeks. Proposal development likely involves systems that have been in place several years. Careful proposal analysis by Government personnel is essential for an effective exchange. Marking the proposal provides a clear reference to guide the exchange.

- Developing initial questions. Each Government analyst should develop initial exchange questions during the analysis. Some questions may be answered later in the analysis, but preparing the questions during analysis will eliminate time wasted reconstructing the question at a later time. More importantly, it will assure that a particular concern is not lost in the rush to complete preparations for the exchange. Questions should deal directly with each issue involved in a non-threatening way, such as:

- How was the estimate developed?

- What is to be provided by the proposed task listed on (specific) page number?

- When will proposed effort be finished?

- Who will accomplish the proposed effort?

- Why is the level of proposed efforts needed?

- How does the proposed effort relate to the contract requirements?

- Reviewing the initial questions. After the proposal analysis is completed, the technical analyst should review initial questions to assure that the:

- Questions do not unwittingly give away potential Government positions or other confidential information.

- Analyst is completely familiar with the questions so that the analyst can concentrate on listening and verifying answers during the exchange session.

- Providing initial questions to the team leader.

Pricing Analyst Preparation. For most contract actions, the contracting officer or the contract specialist is the pricing analyst -- the expert who analyzes material prices, labor rates, and indirect cost rates. The cognizant auditor typically is not a member of the exchange team, but provides advice and assistance.

For larger more complex contract actions, there may be a cost/price analyst assigned. For even larger contract actions, the cognizant auditor may join the team.

Pricing analyst preparation includes the following:

- Analyzing the proposal and obtaining related information. In particular, detailed information on rates and factors may not be contained in the proposal under analysis. Instead they may be contained in one or more forward pricing rate proposal(s). The pricing analyst must obtain enough information to analyze the proposed rates and factors used in proposal preparation. Normally, that requires close liaison with the cognizant auditor and administrative contracting officer (ACO) when one is assigned to the contractor.

- Developing initial questions. Questions should deal directly with each issue involved in a non-threatening way, such as:

- How does the proposed material unit cost compare with recent contractor experience?

- What steps were used to develop and apply the escalation factor for unit material costs?

- What points were considered in key make-or-buy decisions?

- What steps were used to estimate direct labor rates?

- What steps were used to estimate indirect cost rates?

- Reviewing the initial questions. After the proposal analysis is completed, the pricing analyst should review initial questions to assure that the:

- Questions do not unwittingly give away potential Government positions or other confidential information.

- Analyst is completely familiar with the questions so that the analyst can concentrate on listening and verifying answers during the exchange session.

- Providing all questions to the team leader.

Business Terms Analyst Preparation. For most contract actions, the contracting officer or the contract specialist is also the business analyst -- the expert responsible for analyzing proposed terms and conditions. In fact, for most contract actions, little analysis is required at this point, because the contractor accepts the Government's terms and conditions as presented in the solicitation or contract modification.

For more complex contract actions, the ACO, contract administration specialists, legal counsel, and others may be involved in analyzing proposed terms and conditions.

Preparation must center on how proposed terms and conditions will affect the contractual relationship.

- Analyzing the proposal and obtaining related information. Normally, the analysis will center on the legality and advisability of the proposed business terms.

- Developing initial questions. Normally, questions should be carefully coordinated with all Government activities affected.

- Providing all questions to the team leader.

2.4 Conducting Face-To-Face Exchanges

Orientation. The face-to-face exchange session should begin with an orientation. The contents of the orientation will typically depend on numerous factors including: the size of the Government and contractor teams participating in the exchange, the location of the exchange, the procedures for the exchange, and the complexity of the issues involved.

- Greeting. Create a cordial atmosphere by exchanging pleasantries and compliments. At the very least, express appreciation to the contractor for participating in the acquisition. If you are the host, welcome the contractor team to your facility. If you are the visitor, thank the contractor for the opportunity to visit the contractor's facility.

- Introductions. If all the parties involved do not know each other, participants should be asked to introduce themselves and describe their role in the exchange session. If the group is large, circulate a roster to obtain a permanent record of information such as each attendee's name, job title, business address, and telephone number.

- Facility Orientation. If you plan a group meeting in a single conference room, the facility orientation can be limited to information such as security restrictions and the location of facilities such as refreshment areas and rest rooms. If Government team members will separate and meet with different contractor experts in different locations throughout the contractor's facility, an orientation on the entire facility may be appropriate.

- Agenda Review. If you plan a group meeting in a single conference room, the agenda will normally be limited to an overview of the topics to be covered and anticipated length of the exchange session. If you expect the session to continue over more than one day, you should review the projected daily schedule.

- Session Purpose. Emphasize that the purpose of the session is to obtain information, not negotiate.

Exchange Interviews. The key to the exchange process is the Government exchange interview of contractor personnel. The whole Government team can work together to conduct each interview, subsets of the team can conduct different interviews simultaneously, individual team members can conduct the interviews, or different combinations can be used for different interviews.

Team members conducting an exchange interview must present a professional image, listen carefully, and actively encourage an open exchange.

The basic interview skills include:

- Questioning. This is the backbone of the exchange interview. The best questioning style largely depends on the subject matter and the personality of the person being interviewed.

- Detailed questions on specific issues are normally recommended, because of the limited time available for interviews. This can be used to get to the heart of a specific issue without unnecessary and sometimes confusing discussion.

- Wide-ranging and non-directed questions can be particularly useful when the Government analyst desires to obtain broad information on contractor processes and systems. In addition, some people resent detailed questioning, because they feel they are being interrogated. As a result, they are prone to be more candid in responding to wide-ranging questions.

- Probing. This technique is useful when the interviewee's answers are either vague or qualified. Probing:

- Typically involves a series of questions concerning the same issue. The initial questions are general. Each successive question is more specific and designed to elicit a more detailed response. The goal is a full and adequate answer.

- May also involve asking the same question in different ways. When the answer is not satisfactory, you may rephrase it and ask it again. Alternatively, you may allow a period of time to pass before rephrasing and asking it again. This process continues until the interviewee provides an adequate answer.

- May lead to interviewee frustration and anger. Do not allow a question to go unanswered. You might ask the question another way to assure clarity and understanding. If the interviewee cannot or will not answer candidly, the team leader may need to elicit contractor management support in obtaining an acceptable answer.

- Listening. Listening is as vital to communication as talking. Inadequate communication is too often caused by inadequate listening. Moreover, the art of listening is of special significance during fact-finding because the purpose of the sessions is to absorb answers by listening.

- Understanding. Differences in language or interpretation can often lead to misunderstandings and even unintentional disputes. There are several techniques that you might consider using to assure understanding:

- Share relevant portions of the Government's evaluation of the contractor's proposal with the contractor to demonstrate points that Government evaluators did not understand.

- Rephrase the interviewee's statement and ask whether your interpretation is correct.

- Use a form similar to the example on the next page to document understanding.

|

Exchange Interview

Date: _______________

Subject: ________________________________________________________________

Government Team Member(s) ______________________________________________

Contractor Team Member(s) ________________________________________________

Summary (topics, questions, answers, and exhibits): ______________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Documents Reviewed: _____________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________

Action Items: ____________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________

__________________________ __________________________

Government Representative Contractor Representative

|

Government Caucus. As information is gathered, Government team members should caucus periodically to compare notes about the information obtained so far. The caucus may highlight conflicting information provided by the contractor or confirm the viability of supporting information provided by the contractor. Accordingly, a caucus may result in additional questions, confirmation of progress, or the confirmation that Government concerns about the contractor's proposal have been answered.

Conclusion. The face-to-face exchange should continue until both parties agree on the facts or at least one party feels that a break is necessary because the needed facts are not currently available. Neither party's position can be realistic until there is mutual understanding concerning the facts.

Sessions should end with a formal conclusion where the Government team leader:

- Summarizes the important findings during the session.

- Identifies open issues when questions remain.

- Asks the contractor's representative for comment.

- Expresses appreciation to the contractor.

- Schedules another exchange session if necessary.

- Schedules a tentative time for negotiations, if another exchange is not needed.

Document Results. Document exchange results. The documentation should identify the information received and how it was used on the contracting decision process. Usually, the documentation is prepared by the team leader. However, in large complex negotiations, the team leader may designate another team member as the team recorder.

2.5 Using Exchange Results

Use Depends on Purpose. Your use of exchange results will depend on the reason for the exchange.

Use of Clarification Results (FAR 15.306(a)). The results of a clarification can be considered in the award decision without negotiation. For example, if the contractor demonstrates the relevance of past experience, that experience should be considered in making the contract award decision. Unrelated experience should not be considered.

Use of Communications Results (FAR 15.306(b)). The results of a communication can be considered in establishing the competitive range. For example, if the contractor's response to adverse past performance information does not refute that information, that failure might lower the firm's overall rating enough to exclude the firm from the competitive range.

Use of Other Exchanges Before Competitive Negotiations (FAR 15.306(d)). The results from exchanges that take place after establishment of the competitive range but before contract negotiations, may be used to complete proposal evaluation. Those results should be considered in developing negotiation objectives.

If the exchange reveals serious flaws in the request for proposals, the contracting officer should consider amending the solicitation or canceling the solicitation and resoliciting.

Use of Fact-Finding Results. The results from fact-finding should be used to reevaluate preliminary prenegotiation objectives. Normally, the Government and the contractor positions should be closer together, based on the results of the fact-finding.

During the fact-finding, the Government team should have:

- Obtained a mutual understanding with the contractor on the pertinent facts pertaining to the offer;

- Tested the validity of the issues and positions identified prior to the exchange;

- Verified the facts presented in the proposal;

- Verified or refuted proposal assumptions; and

- Identified the contractor position on key negotiation issues and the relative importance of each position.