|

Print Page | ||||||||||||||||||||

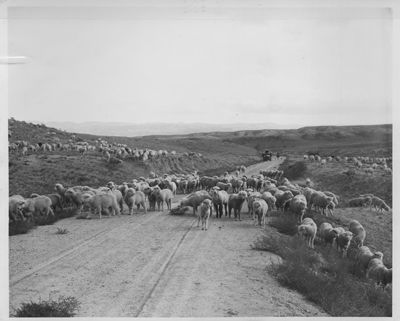

| Grazing | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contact: Tom Gorey, BLM Public Affairs (202-912-7420)

New Video Clips Fact Sheet on the BLM’s Management of Livestock GrazingGrazing on Public LandsThe Bureau of Land Management, which administers about 245 million acres of public lands, manages livestock grazing on 155 million acres of those lands, as guided by Federal law. The terms and conditions for grazing on BLM-managed lands (such as stipulations on forage use and season of use) are set forth in the permits and leases issued by the Bureau to public land ranchers. The BLM administers nearly 18,000 permits and leases held by ranchers who graze their livestock, mostly cattle and sheep, at least part of the year on more than 21,000 allotments under BLM management. Permits and leases generally cover a 10-year period and are renewable if the BLM determines that the terms and conditions of the expiring permit or lease are being met. The amount of grazing that takes place each year on BLM-managed lands can be affected by such factors as drought, wildfire, and market conditions.

A Brief History of Public Lands GrazingDuring the era of homesteading, Western public rangelands were often overgrazed because of policies designed to promote the settlement of the West and a lack of understanding of these arid ecosystems. In response to requests from Western ranchers, Congress passed the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 (named after Rep. Edward Taylor of Colorado), which led to the creation of grazing districts in which grazing use was apportioned and regulated. Under the Taylor Grazing Act, the first grazing district to be established was Wyoming Grazing District Number 1 on March 23, 1935. Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes created a Division of Grazing within the Department to administer the grazing districts; this division later became the U.S. Grazing Service and was headquartered in Salt Lake City. In 1946, as a result of a government reorganization by the Truman Administration, the Grazing Service was merged with the General Land Office to become the Bureau of Land Management.

The unregulated grazing that took place before enactment of the Taylor Grazing Act caused unintended damage to soil, plants, streams, and springs. As a result, grazing management was initially designed to increase productivity and reduce soil erosion by controlling grazing through both fencing and water projects and by conducting forage surveys to balance forage demands with the land’s productivity (“carrying capacity”). These initial improvements in livestock management, which arrested the degradation of public rangelands while improving watersheds, were appropriate for the times. But by the 1960s and 1970s, public appreciation for public lands and expectations for their management rose to a new level, as made clear by congressional passage of such laws as the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976. Consequently, the BLM moved from managing grazing in general to better management or protection of specific rangeland resources, such as riparian areas, threatened and endangered species, sensitive plant species, and cultural or historical objects. Consistent with this enhanced role, the Bureau developed or modified the terms and conditions of grazing permits and leases and implemented new range improvement projects to address these specific resource issues, promoting continued improvement of public rangeland conditions. Current Management of Public Lands Grazing

Legal Mandates relating to Public Lands GrazingLaws that apply to the BLM’s management of public lands grazing include the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, and the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978. Expenditures and CollectionsIn Fiscal Year 2015, the BLM was allocated $79 million for its rangeland management program. Of that figure, the agency spent $36.2 million (46 percent) on livestock grazing administration. The other funds covered such activities as weed management, rangeland monitoring (not related to grazing administration), planning, water development, vegetation restoration, and habitat improvement. In 2015, the BLM collected $14.5 million in grazing fees (see section on grazing fee below). The receipts from these annual fees, in accordance with legislative requirements, are shared with state and local governments.Federal Grazing FeeThe Federal grazing fee, which applies to Federal lands in 16 Western states on public lands managed by the BLM and the U.S. Forest Service, is calculated annually by using a formula originally set by Congress in the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978. Under this formula, as modified and extended by a presidential Executive Order issued in 1986, the grazing fee cannot fall below $1.35 per animal unit month (AUM); also, any fee increase or decrease cannot exceed 25 percent of the previous year’s level. (An AUM is the amount of forage needed to sustain one cow and her calf, one horse, or five sheep or goats for a month.) The grazing fee for 2016 is $2.11 per AUM, as compared to the 2015 fee of $1.69. The Federal grazing fee is computed by using a 1966 base value of $1.23 per AUM for livestock grazing on public lands in Western states. The figure is then adjusted each year according to three factors – current private grazing land lease rates, beef cattle prices, and the cost of livestock production. In effect, the fee rises, falls, or stays the same based on market conditions, with livestock operators paying more when conditions are better and less when conditions have declined. Thus, the grazing fee is not a cost-recovery fee, but a market-driven fee. Number of Livestock on BLM-managed Lands

Grazing Permit SystemAny U.S. citizen or validly licensed business can apply for a BLM grazing permit or lease. To do so, one must either:

The first alternative happens when base property (a private ranch) is sold or leased to a new individual or business; the buyer or lessee then applies to the BLM for the use of grazing privileges associated with that property. The second alternative would happen when a rancher wants to transfer existing public land grazing privileges to another party while keeping the private ranch property. Before buying or leasing ranch property, it is advisable to contact the BLM Field Office that administers grazing in the area of the base property. The BLM has information on the status of the grazing privileges attached to the base property, including the terms and conditions of the associated grazing permit or lease that authorizes the use of those privileges and other important information. All applicants for grazing permits or leases must meet the qualifications for public land grazing privileges that are specified in the BLM’s grazing regulations. The Role of Livestock Grazing on Public Lands TodayGrazing, which was one of the earliest uses of public lands when the West was settled, continues to be an important use of those same lands today. Livestock grazing now competes with more public land uses than it did in the past, as other industries and the general public look to these lands as sources of both conventional and renewable energy and as places for outdoor recreational opportunities, including off-highway vehicle use. Among the key issues that face public land managers today are drought, severe wildfires, invasive plant species, and the effects of urbanization on once-remote parcels of land. Public rangelands and the private ranches adjacent to them maintain open spaces in the fast-growing West. Together they will continue to help write the West’s history while shaping the region’s character in the years to come.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||