Ventricular system

| Brain: Cerebral ventricles | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

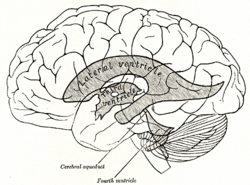

| Scheme showing relations of the ventricles to the surface of the brain. | ||

|

||

| Drawing of a cast of the ventricular cavities, viewed from above. | ||

| NeuroNames | ancil-192 | |

| MeSH | Cerebral+Ventricles | |

The ventricular system is a set of structures containing cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. It is continuous with the central canal of the spinal cord.

Contents |

[edit] Components

The system comprises four ventricles:

- right and left lateral ventricles (the first and second ventricles)

- third ventricle

- fourth ventricle

There are several small holes or foramina that connect these ventricles, though only the first two of the list below are generally considered part of the ventricular system:

| Name | From | To |

| right and left interventricular foramina (Monro) | lateral ventricles | third ventricle |

| cerebral aqueduct (Sylvius) | third ventricle | fourth ventricle |

| Median aperture (Magendie) | fourth ventricle | subarachnoid space/cisterna magna |

| right and left Lateral aperture (Luschka) | fourth ventricle | subarachnoid space/cistern of great cerebral vein |

[edit] Ventricles

[edit] Flow of cerebrospinal fluid

The ventricles are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) which bathes and cushions the brain and spinal cord within their bony confines. Cerebrospinal fluid is produced by modified ependymal cells of the choroid plexus found in all components of the ventricular system except for the cerebral aqueduct and the posterior and anterior horns of the lateral ventricles. CSF flows from the lateral ventricles via the foramina of Monro into the third ventricle, and then the fourth ventricle via the cerebral aqueduct in the brainstem. From there it can pass into the central canal of the spinal cord or into the cisterns of the subarachnoid space via three small foramina: the central foramen of Magendie and the two lateral foramina of Luschka.

The fluid then flows around the superior sagittal sinus to be reabsorbed via the arachnoid villi into the venous system. CSF within the spinal cord can flow all the way down to the lumbar cistern at the end of the cord around the cauda equina where lumbar punctures are performed.

The aqueduct between the third and fourth ventricles is very small, as are the foramina, which means that they can be easily blocked, causing high pressure in the lateral ventricles. This is a common cause of hydrocephalus (known colloquially as "water on the brain"), which is an extremely serious condition due to both the damage caused by the pressure as well as nature of whatever caused the block (e.g. a tumour or inflammatory swelling). The cavities of the cerebral hemispheres are called lateral ventricles, or 1st & 2nd ventricles. These two ventricles open commonly into the 3rd ventricle by a common opening called the foramen of Monro.

[edit] Protection of the brain

The brain and spinal cord are covered by a series of tough membranes called meninges, which protect these organs from rubbing against the bones of the skull and spine. The cerebrospinal fluid within the skull and spine is found between the pia mater and the Arachnoid and provides further cushioning.

The Cerebrospinal Fluid that is produced in the ventricular system has three main purposes: buoyancy, protection, and chemical stability. The protection purpose comes into play with the meninges: pia mater, and the Arachnoid layer. The CSF is there to protect the brain from striking the cranium when the head is jolted. CSF provided buoyancy and support to the brain against gravity. The buoyancy protects the brain since the brain and CSF are similar in density; this makes the brain float in neutral buoyancy, suspended in the CSF. This allows the brain to attain a decent size and weight without resting on the floor of the cranium, which would kill nervous tissue.[1][2]

[edit] Role in disease or disorder

Diseases of the ventricular system include abnormal enlargement (hydrocephalus) and inflammation of the CSF spaces (meningitis, ventriculitis) caused by infection or introduction of blood following trauma or hemorrhage.

Interestingly, scientific study of CT scans of the ventricles in the late 1970s revolutionized the study of mental disorder. Researchers found that individuals with schizophrenia had (in terms of group averages) enlarged ventricles compared to healthy subjects. This became the first "evidence" that schizophrenia was biological in origin and led to a reinvigoration of the study of such conditions via modern scientific techniques. Whether the enlargement of the ventricles is a cause or a result of schizophrenia has not yet been ascertained, however. Still, this founding was not revolutionary at the time, as enlarged ventricles are found in various other types of organic dementia. In fact, ventricle volumes have been found to be "mainly explained by environmental factors"[3] and to be extremely diverse between individuals, such that the percentage difference in group averages in schizophrenia studies (+16%) has been described as "not a very profound difference in the context of normal variation" (ranging from 25% to 350% of the mean average).[4] Nowadays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has superseded the use of CT in research into the role of ventricular abnormalities in psychiatric illness.

[edit] Development

The structures of the ventricular system are embryologically derived from the centre of the neural tube (the neural canal).

[edit] In brainstem

As the part of the primitive neural tube that will become the brain stem develops, the neural canal expands dorsally and laterally, creating the fourth ventricle, whereas the neural canal that does not expand and remains the same at the level of the midbrain superior to the fourth ventricle forms the cerebral aqueduct. Likewise, the neural canal in the spinal cord that does not change forms the central canal.

[edit] Additional images

[edit] References

- ^ Klein, S.B., & Thorne, B.M. Biological Psychology. Worth Publishers: New York. 2007.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology. The Unit of Form and Function. 5th Edition. McGraw-Hill: New York. 2007

- ^ Peper, Jiska S.; Brouwer, RM; Boomsma, DI; Kahn, RS; Hulshoff Pol, HE (2007). "Genetic influences on human brain structure: A review of brain imaging studies in twins". Human Brain Mapping 28 (6): 464–73. doi:10.1002/hbm.20398. PMID 17415783.

- ^ Allen JS, Damasio H, Grabowski TJ (August 2002). "Normal neuroanatomical variation in the human brain: an MRI-volumetric study". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 118 (4): 341–58. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10092. PMID 12124914.

[edit] External links

- ventricular system and CSF (concise description, University of Washington)

- CSF at answers.com (brief description, excellent diagram of CSF flow)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||