“If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.”

— Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan

When Sol Goldstein heard that the National Socialist (Nazi) Party of America was planning to march through Skokie, Illinois, in 1977, he was outraged.

Sol was a Holocaust survivor, one of approximately 6,000 who lived in Skokie, a quiet suburb of Chicago notable for its large Jewish population. Many residents, like Goldstein, had seen their family members tortured and killed by the Nazis during World War II, and the idea of swastika-adorned, jackbooted marchers in their town was too much to bear.

Goldstein organized the Jewish community to stop the city from issuing the Nazis a permit to march. He sued the National Socialist Party of America, and was a main witness in the ensuing court battle between the Nazi group and the town. However, despite Goldstein’s testimony about what life had been like in the concentration camp and how much it would affect him to see the symbols of Nazi Germany paraded through his town, the Jewish community of Skokie could not stop the city from issuing the permit to march.

In a series of court decisions that went all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, the courts ruled in favor of the Nazis. The justices held that the National Socialists had a constitutionally protected right to hold a rally and to display swastikas and other signs.

The citizens of Skokie were devastated. They had thought that the government existed to protect them from the Nazis and bigots. How could this have happened?

“Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble …” — U.S. Constitution, Amendment I (1791)

The First Amendment

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution forbids the federal government from preventing someone from speaking or from punishing someone for something they’ve said. It was originally created to protect political speech and keep the government from shutting down newspapers that expressed dissent; however, over time the Supreme Court has interpreted speech to include marches, protests and other forms of expressive conduct. The concept also has expanded to cover hate speech and offensive conduct. This means that no matter how offensive someone’s ideas or how upsetting their imagery, the First Amendment protects their ability to be heard.

That’s why Skokie had to issue the Nazis a permit to march. Denying their right to assemble would have been the equivalent of preventing them from speaking. That’s also why today hateful messages and radical organizations remain legal.

Checking government power

The Founding Fathers were suspicious of government power. The First Amendment was ratified soon after the Constitution itself to address popular concern that the government might suppress political dissent.

“Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government,” said Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers and an author of the Constitution. “When this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved.”

Once you start trying to decide what is permissible speech and what is not, the question becomes “Who is the censor?” explains Burton Caine, a professor of law at Temple University in Philadelphia. The government’s power to punish people for what they say “has been used by governments throughout history, all over the world,” to suppress dissent and hurt political minorities. The founders protected us from that, Caine concludes.

The only way to truly protect free speech is to protect it for everyone, even those whose opinions are intolerable to many others. That way no matter who comes to power, the free-speech rights of political protesters and minorities cannot be repressed.

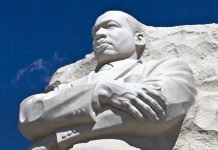

This protection was never more evident than during the civil rights era when courts upheld the rights of protesters, like Martin Luther King Jr., to march against the injustice of racial segregation. Despite the opposition of local governments, King’s nonviolent speeches, sit-ins and protests were allowed to go forward because the First Amendment restricted what those governments could do to stop him. In many cases, anticipating the logic that would allow the Nazis to march in Skokie, courts ruled that cities couldn’t deny civil rights protesters the right to march just because they didn’t like what the activists had to say.

From the street to the web

Today, much racist and offensive speech occurs on the internet. Social media sites like Twitter and Facebook struggle with how to handle online hate speech, and groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights advocacy group, and the Muslim Advocates organization have spent years documenting and fighting hate speech and racism online.

Yet, just as in Skokie, the courts have repeatedly protected the rights of those who make hateful comments and post racist images, so long as their speech does not cross the line into direct and credible threats of violence.

Speech that leads to violence is not protected

Despite the First Amendment, courts do not protect all speech. The test is whether the speech can reasonably be expected to lead to violence or other lawless action. Basically, the courts have ruled that if someone makes a direct threat against another person or incites a group to commit imminent violence, the speech is not protected and the government can intervene.

.

Thus, for instance, when the leader of the Ku Klux Klan, a white racist organization, gave a speech in Ohio calling for revenge against blacks, Jews and the U.S. government, the Supreme Court found that he could not be arrested for inciting violence because he was not threatening anyone specifically.

But when the Klan threatened a specific black family in Virginia, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment did not protect their actions and the government could prosecute the offending parties.

As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. once famously put it, “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” Holmes’ point: When you create a “clear and present danger” to others through your speech, that speech is not protected.

Drawing the line “has never been easy and is never going to be easy,” said John Shuford, who teaches conflict resolution at Portland State University in Oregon and is the founder of the Hate Studies Policy Research Center. “We have to accept the sometimes distasteful speaker and the sometimes distasteful premise that [people] get to say things that are hurtful and inflammatory,” he said. But also recognize that when those people cross the line, when they “take that step too far,” they break the law.

Fighting offensive speech

The question then, asks Shuford, is “What is our best approach to dealing with speech and activity that is controversial, maybe offensive, maybe inflammatory, but that doesn’t necessarily cross any lines of otherwise illegal conduct?”

.

The answer is robust debate, and the idea that the best way to fight ideas you disagree with is to put forward your own.

In this competition of ideas, the government doesn’t outlaw speech that it disagrees with but instead assures that everyone may speak and confront ideas that they find offensive. By defending individual rights, this approach ensures that everyone can voice their opinions regardless of who controls the levers of power.

The community in Skokie couldn’t deny the Nazis their march permit, but they could make sure the Nazis weren’t the only voices heard. The city of Skokie worked with the Jewish community to build a Holocaust museum to commemorate those who had died and to ensure that people will always remember what happens when racist ideology goes unopposed.

![Inaugural gown previews a first lady’s style [video] A grid of images showing women in formal gowns (© AP Images; © Getty)](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20170124234028im_/https://share.america.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Gowns_w_Background-1-218x150.jpg)

![Immigrants find success in Silicon Valley’s venture capital industry [video] Two people in front of freshdesk logo (VOA)](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20170124234028im_/https://share.america.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/maxresdefault-2-218x150.jpg)

![One approach for bringing jobs to low-income neighborhoods [video] David Williamson smiling, with text added (State Dept.)](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20170124234028im_/https://share.america.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/maxresdefault-17-218x150.jpg)

![Look what has happened since the 2015 climate pact was adopted [video] Illustration of windmills on green hills (State Dept.)](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20170124234028im_/https://share.america.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Screen-Shot-2016-12-16-at-11.54.40-AM-218x150.jpg)

![Rock’s Hall of Fame picks its 2017 inductees [video] One man singing, another playing guitar (© AP Images)](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20170124234028im_/https://share.america.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/AP_16355457878731-218x150.jpg)