Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

Global map of the seven subpopulations of Leatherback and their nesting sites

Map derived from Wallace et al. (2013)

(click for larger view PDF)

Leatherback turtle hatchling

(Dermochelys coriacea)

Photo: N.Pilcher

Photo: A. Eilers, Permit number 1596

Photo: A. Eilers, Permit number 1596

Did You Know?

- The largest leatherback on record (a male) stranded on the coast of Wales in 1988 and weighed almost 2,020 lbs (915 kg).

- Leatherbacks can dive deeper than 3,900 ft (1,200 m)!

Kids' Times: Leatherback [pdf]

Credit: NOAA

Credit: Scott R. Benson,

NMFS Southwest Fisheries Science Center

NMFS Research Permit #1596

Leatherback turtle esophagus

(Dermochelys coriacea)

Photo: Karumbé, Sea Turtles of Uruguay

Video: Leatherback Turtles- Pacific Upwelling & Jellyfish ![]()

NMFS Southwest Fisheries Science Center

Videos: Leatherback Turtles in the Pacific Ocean

NMFS Southwest Fisheries Science Center

Videos: Leatherback Turtles in the Solomon Islands

NMFS Southwest Fisheries Science Center

Photo: R. Tapilatu (left), S.R. Benson (right)

Status

ESA Endangered - throughout its range

CITES Appendix I - throughout its range

Pacific leatherback sea turtles are one of NOAA Fisheries' Species in the Spotlight

Pacific leatherback sea turtles are genetically and biologically unique. They migrate extreme distances across the Pacific from nesting to foraging areas, and are generally larger in size than Atlantic leatherbacks. Pacific leatherbacks are split into two subpopulations -- Western and Eastern Pacific leatherbacks -- based on range distribution and biological and genetic characteristics. Western Pacific leatherbacks nest in the Indo-Pacific and migrate back to feeding areas off the Pacific coast of North America. Eastern Pacific leatherbacks nest along the Pacific coast of the Americas in Mexico and Costa Rica. Unlike populations of Atlantic leatherbacks, Pacific leatherback populations have plummeted in recent decades: Western Pacific leatherbacks have declined more than 80 percent and Eastern Pacific leatherbacks have declined by more than 97 percent. Extensive egg harvest and bycatch in fishing gear are the primary causes of these declines.

- Leatherback Spotlight Species 5-Year Action Plan

- Our Southwest Fisheries Science Center leatherback sea turtle research

- Recovery plan for Pacific leatherback sea turtles

- Other NOAA Fisheries Species in the Spotlight

Species Description

| Weight: | Adult: up to 2,000 pounds (900 kg) Hatchling: 1.5-2 ounces (40-50 g) |

| Length: | Adult: 6.5 feet (2 m) Hatchling: 2-3 inches (50-75 cm) |

| Appearance: | primarily black shell with pinkish-white coloring on their belly |

| Lifespan: | unknown |

| Diet: | soft-bodied animals, such as jellyfish and salps, and pyrosomes |

| Behavior: | females lay clutches of approximately 100 eggs several times during a nesting season, typically at 8-12 day intervals |

The leatherback is the largest turtle--and one of the largest living reptiles--in the world.

The leatherback is the only sea turtle that doesn't have a hard bony shell. A leatherback's top shell (carapace) is about 1.5 inches (4 cm) thick and consists of leathery, oil-saturated connective tissue overlaying loosely interlocking dermal bones. Their carapace has seven longitudinal ridges and tapers to a blunt point, which help give the carapace a more hydrodynamic structure.

Their front flippers don't have claws or scales and are proportionally longer than in other sea turtles. Their back flippers are paddle-shaped. Both their ridged carapace and their large flippers make the leatherback uniquely equipped for long distance foraging migrations.

Female leatherbacks remigrate to their respective nesting sites at 2-3 year intervals. Females nest several times during a nesting season, typically at 8-12 day intervals and lay clutches of approximately 100 eggs. After about 2 months, leatherback hatchlings emerge from the nest and have white striping along the ridges of their backs and on the margins of the flippers.

Leatherbacks don't have the crushing chewing plates characteristic of other sea turtles that feed on hard-bodied prey (Pritchard 1971). Instead, they have pointed tooth-like cusps and sharp-edged jaws that are perfectly adapted for a diet of soft-bodied pelagic (open ocean) prey, such as jellyfish and salps. A leatherback's mouth and throat also have backward-pointing spines that help retain such gelatinous prey. Leatherbacks can dive to depths of 4,200 feet (1,280 meters)—deeper than any other turtle—and can stay down for up to 85 minutes.

The global population of leatherbacks comprises seven biologically and geographically subpopulations, which are located in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Ocean. The subpopulations with ranges overlapping U.S. territory are the West Pacific, East Pacific, and Northwest Atlantic leatherbacks. Western Pacific leatherbacks feed off the Pacific Coast of North America, and migrate across the Pacific to nest in Malaysia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. Eastern Pacific leatherbacks, on the other hand, nest along the Pacific coast of the Americas in Mexico and Costa Rica. Although the leatherback populations in the Caribbean and Atlantic Ocean are generally stable or increasing, the situation in the Pacific Ocean is dire: in recent decades, Western Pacific leatherbacks have declined more than 80 percent and Eastern Pacific leatherbacks have declined by more than 97 percent.

Habitat

Leatherbacks are commonly known as pelagic (open ocean) animals, but they also forage in coastal waters. In fact, leatherbacks are the most migratory and wide ranging of sea turtle species.

Thermoregulatory adaptations such as a counter-current heat exchange system, high oil content, and large body size allow them to maintain a core body temperature higher than that of the surrounding water, thereby allowing them to tolerate colder water temperatures. For example:

- Nesting female leatherbacks tagged in French Guiana have been found along the east coast of North America as far north as Newfoundland.

- Atlantic Canada supports one of the largest seasonal foraging populations of leatherbacks in the Atlantic.

- Leatherbacks have also been tagged with satellite transmitters at sea off Nova Scotia (James et al., 2005)

Leatherbacks mate in the waters adjacent to nesting beaches and along migratory corridors. After nesting, female leatherbacks migrate from tropical waters to more temperate latitudes, which support high densities of jellyfish prey in the summer.

Pacific Leatherback

Western Pacific leatherbacks engage in one of the greatest migrations of any air-breathing aquatic marine vertebrate, swimming from tropical nesting beaches in the western Pacific (primarily Papua Barat, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands) to foraging grounds in the neritic eastern North Pacific. The nearly 7000-mile trans-Pacific journey through exclusive economic zones of multiple Pacific nations and international water requires10-12 months to complete. (See the map below)

The Eastern Pacific Leatherback subpopulation nests along the Pacific coast of the Americas from Mexico to Ecuador, and marine habitats extend from the coastline westward to approximately 130°W and south to approximately 40°S. This subpopulation is genetically distinct from all other Leatherback subpopulations, despite having some areas of overlap with the Western Pacific subpopulation (Dutton et al. 1999).

Atlantic Leatherback

In the Atlantic nesting female leatherbacks tagged in French Guiana have been found along the east tracked, using satellite transmitters, to the west coast of North America as far north as Newfoundland. Atlantic Canada supports one of the largest seasonal foraging populations of leatherbacks in the Atlantic. Leatherbacks have also been tagged with satellite transmitters at sea off Nova Scotia (James et al., 2005).

Critical Habitat

|

|

U.S. West Coast

NMFS designated critical habitat to provide protection for endangered leatherback sea turtles along the U.S. West Coast in January 2012 (77 FR 4170).

Atlantic

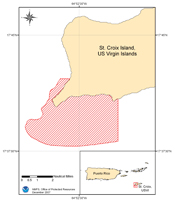

U.S. Virgin Islands

In 1979, we designated critical habitat for leatherback turtles to include the coastal waters adjacent to Sandy Point, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Puerto Rico

On February 2, 2010, the Sierra Club petitioned [pdf] us to revise the critical habitat designation for leatherback sea turtles to include waters adjacent to a major nesting beach in Puerto Rico. We published a negative 90-day finding on the petition [pdf] on July 16, 2010, which found the petition did not present substantial scientific information indicating that the critical habitat revision was warranted for leatherback sea turtles.

The Sierra Club submitted a new petition [pdf] on November 2, 2010 to revise the critical habitat designation to again include waters in Puerto Rico. On August 4, 2011, NMFS and FWS published a 90-day finding and 12-month determination (76 FR 47133) on the petition to revise critical habitat. NMFS denied the petitioned revision in June 2012 (77 FR 32909).

Distribution

Leatherbacks have the widest global distribution of all reptile species. The leatherback turtle is distributed worldwide in tropical and temperate waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. It is also found in small numbers as far north as British Columbia, Newfoundland, and the British Isles, and as far south as Australia, Cape of Good Hope, and Argentina.

Pacific Leatherback

Pacific leatherback turtle nesting grounds are located in tropical latitudes in the eastern and western Pacific around the world. The largest remaining nesting assemblages are found on the coasts of

- Northern South America. New Guinea and Papua New Guinea

- West Africa solomon Islands

- Mexico

- Costa Rica

Atlantic Leatherback

Globally, the most important nesting beach for leatherbacks in the eastern Atlantic lies in Gabon, Africa. The largest nesting population at present in the western Atlantic is in French Guiana. Within the U.S., there are minor--though the most significant nesting in the U.S.--nesting colonies in:

- Caribbean, primarily

- Puerto Rico

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- Southeast Florida

Adult leatherbacks are capable of tolerating a wide range of water temperatures and have been sighted along the entire continental east coast of the United States as far north as the Gulf of Maine and south to Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and into the Gulf of Mexico.

The distribution and developmental habitats of juvenile leatherbacks are poorly understood. In an analysis of available sightings (Eckert 2002), researchers found that leatherback turtles smaller than about 3 feet (100 cm) carapace length were only sighted in waters about 79°F (26°C) or warmer, while adults were found in waters as cold as 32-59°F (0-15°C) off Newfoundland (Goff and Lean 1988).

Population Trends

Because adult female leatherbacks frequently nest on different beaches, nesting population estimates and trends are especially difficult to monitor. However, it is estimated that the global population has declined an estimated 40% over the past three generations (Wallace et al. 2015).

Pacific Leatherback

Western pacific and Eastern Pacific leatherbacks continue to decline. Western Pacific leatherbacks have declined more than 80% over the last three generations, and Eastern Pacific leatherbacks have declined by more than 97% over the last three generations. Of the Eastern Pacific leatherbacks, the Mexico nesting population -- once considered to be the world’s largest with 65 percent of the worldwide population -- is now less than one percent of its estimated size in 1980.

Atlantic Leatherback

In the Caribbean, Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, leatherback populations are generally increasing. In the United States, the Atlantic coast of Florida is one of the main nesting areas in the continental United States. Data from this area reveals a general upward trend of, though with some fluctuation. Florida index nesting beach data from 1989-2014, indicate that number of nests at core index nesting beach ranged from 27 to 641 in 2014. In the U.S. Caribbean,nesting in Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and the U.S. Virgin Islands continues to increase as well,with some shift in the nesting between these two islands.

Threats

- harvest of eggs and turtles themselves

- incidental capture in fishing gear, such as

- gillnets

- longlines

- trawls

- traps/ pots

- dredges

- general threats to marine turtles

Leatherback turtles face threats on both nesting beaches and in the marine environment. The greatest causes of decline and the continuing primary threats to leatherbacks worldwide are long-term harvest and incidental capture in fishing gear. Harvest of eggs and adults occurs on nesting beaches while juveniles and adults are harvested on feeding grounds. Incidental capture primarily occurs in gillnets, but also in trawls, traps and pots, longlines, and dredges. Additionally, leatherbacks are threatened by the existence of marine debris such as plastic bags and balloons, which they often consume after mistaking them for their preferred prey, jellyfish. Together these threats are serious ongoing sources of mortality that adversely affect the species' recovery. It is estimated that only about one in a thousand leatherback hatchlings survive to adulthood.

For more information, please visit our threats to marine turtles page.

Conservation Efforts

The highly migratory behavior of sea turtles makes them shared resources among many nations. Thus, conservation efforts for sea turtle populations in one country may be jeopardized by activities in another. Protecting sea turtles on U.S. nesting beaches and in U.S. waters alone, therefore, is not sufficient to ensure the continued existence of the species.

Sea turtles are protected by various international treaties and agreements as well as national laws:

- CITES: listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, which prohibits international trade

- CMS: listed in Appendices I and II of the Convention on Migratory Species and are protected under the following auspices of CMS:

- IOSEA: Memorandum of Understanding on the Conservation and Management of Marine Turtles and their Habitats of the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia

- Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Conservation Measures for Marine Turtles of the Atlantic Coast of Africa

- SPAW: protected under Annex II of the Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife Protocol of the Cartagena Convention

- IAC: The U.S. is a party of the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles, which is the only international treaty dedicated exclusively to marine turtles

In the U.S., NOAA Fisheries(NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) have joint jurisdiction for leatherback turtles, with NOAA having the lead in the marine environment and USFWS having the lead on the nesting beaches. Both federal agencies, along with many state agencies and international partners, have issued regulations to eliminate or reduce threats to sea turtles, while working together to recover them.

In the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, we have required measures to reduce sea turtle bycatch in pelagic longline, mid-Atlantic gillnet, Chesapeake Bay pound net, and southeast shrimp and flounder trawl fisheries, such as

- gear modifications

- changes to fishing practices

- time/ area closures

NOAA Fisheries have worked closely with the shrimp trawl fishing industry to develop turtle excluder devices (TEDs) to reduce the mortality of sea turtles incidentally captured in shrimp trawl gear. TEDs that are large enough to exclude even the largest sea turtles are now required in shrimp trawl nets. Since 1989, the U.S. has prohibited the importation of shrimp harvested in a manner that adversely affects sea turtles. The import ban does not apply to nations that have adopted sea turtle protection programs comparable to that of the U.S. (i.e., require and enforce the use of TEDs) or to nations where incidental capture in shrimp fisheries does not present a threat to sea turtles (for example, nations that fish for shrimp in areas where sea turtles do not occur). The U.S. Department of State is the principal implementing agency of this law, while we serve as technical advisor. We provide extensive TED training throughout the world.

We are also involved in cooperative gear research projects designed to reduce sea turtle bycatch in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic pelagic longline fisheries, the Hawaii-based deep set longline fishery, the Atlantic sea scallop dredge fishery, the Chesapeake Bay pound net fishery, and non-shrimp trawl fisheries in the Atlantic and Gulf.

Regulatory Overview

The leatherback turtle was listed under the Endangered Species Act as endangered in 1970.

In 1992, we finalized regulations to require TEDs in shrimp trawl fisheries to reduce interactions between turtles and trawl gear. Since then, we have modified these regulations as new information became available on increasing the efficiency of TEDs (for example, larger TEDs are now required to exclude larger turtles).

We designated critical habitat in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1998 for leatherback turtles for the coastal waters adjacent to Sandy Point, St. Croix, USVI.

In 2012, we designated critical habitat along the U.S. West Coast (77 FR 4170).

We implement measures to reduce sea turtle interactions in fisheries by regulations and permits under the ESA and Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. Since the early 1990s, we have implemented sea turtle conservation measures including:

- TEDs in trawl fisheries

- large circle hooks in longline fisheries

- time and area closures for gillnets

- modifications to pound net leaders

A list of our regulations to protect marine turtles is available on our website.

Taxonomy

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Reptilia

Order: Testudines

Family: Dermochelyidae

Genus: Dermochelys

Species: coriacea

Key Documents

(All documents are in PDF format.)

| Title | Federal Register | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Spotlight Species 5-Year Action Plan | n/a | 01/20/2016 |

| 5-year Review of Leatherback Turtle | n/a | 11/2013 |

| NMFS Initiates 5-year reviews of four sea turtles (Kemp's ridley, olive ridley, leatherback, and hawksbill) | 77 FR 61573 | 10/10/2012 |

|

Critical habitat designated for endangered leatherback sea turtles along the U.S. West Coast |

77 FR 4170 | 01/26/2012 |

Sierra Club Re-Petition to NMFS to revise the critical habitat designation to include waters adjacent to a major nesting beach in Puerto Rico

|

n/a 77 FR 32909 76 FR 25660 |

11/02/2010 06/04/2012 05/05/2011 |

| Sierra Club petition to NMFS and USFWS to revise the critical habitat designation to include nesting beach habitat and waters adjacent to the nesting beach in Puerto Rico | n/a | 02/22/2010 |

|

75 FR 41436 | 07/16/2010 |

|

76 FR 47133 | 08/04/2011 |

|

Proposed Rule to Revise Critical Habitat Designation |

75 FR 319 75 FR 7434 75 FR 5015 |

01/05/2010 02/19/2010 02/01/2010 |

Petition to Revise the Critical Habitat Designation for the Leatherback Sea Turtle

|

n/a 72 FR 73745 |

09/26/2007 12/28/2007 |

| 5-Year Review | n/a | 08/31/2007 |

| Virginia Pound Net Fishery Regulations | 71 FR 36024 | 06/23/2006 |

| Recovery Plan - U.S. Pacific | 63 FR 28359 | 05/22/1998 |

| Status Review of Sea Turtles Listed Under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 | 61 FR 17 | 01/02/1996 |

| TED Regulations for Shrimp Trawls | 57 FR 57348 | 12/04/1992 |

| Recovery Plan - U.S. Caribbean, Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico | n/a | 10/29/1991 |

| Critical Habitat - Sandy Point, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands | 44 FR 17710 | 03/23/1979 |

|

43 FR 12050 | 03/23/1978 |

| ESA Listing Rule | 35 FR 8491 | 06/02/1970 |

More Information

- Kids' Times: Leatherback Sea Turtle [pdf]

- Videos of Leatherback Turtles from Southwest Fisheries Science Center

- Sea Turtle Recovery Planning

- NOAA's National Marine Sanctuaries Encyclopedia

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Leatherback Turtle Species Profile

- More Sea Turtle Related Links

Literature Cited

- Pritchard, P. C. H. (1971). The Leatherback Or Leathery Turtle: Dermochdys Coriacea (No. 1). IUCN.

- Eckert, S.A. 2002. Distribution of juvenile leatherback sea turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, sightings. Marine Ecology Progress Series 230: 289-293.

- Goff, G.P. and J. Lien. 1988. Atlantic leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) in cold water off Newfoundland and Labrador. Canadian Field Naturalist 102 (1):1-5.

- James, M.C., C.A. Ottensmeyer and R.A. Myers. 2005. Identification of high-use habitat and threats to leatherback sea turtles in northern waters: new directions for conservation. Ecology Letters 2005(8):195-201.

- Wallace, B.P., Tiwari, M. and Girondot, M. 2013. Dermochelys coriacea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2015.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 09 June 2015.

Updated: February 10, 2016