NOAA Teacher at Sea

Lynn M. Kurth

Aboard NOAA Ship Rainier

June 20-July 1, 2016

Mission: Hydrographic Survey

Geographical area of cruise: Latitude: 58˚03.973 N Longitude: 153˚34.292 W

Date: July 4, 2016

Weather Data from the Bridge

Sky: Cloudy

Visibility: 10+ Nautical Miles

Wind Direction: 010

Wind Speed: 10 Knots

Sea Wave Height: 0-1 ft. (no swell)

Sea Water Temperature: 11.1° C (51.9° F)

Dry Temperature: 12° C (53.6° F)

Barometric (Air) Pressure: 1013.3 mb

Science and Technology Log

Throughout my experience as a Teacher at Sea, it has been evident that the ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected. This was apparent from my very first evening in Homer when I came across an eagle poised next to its colossal nest assembled in the middle of three rusty pier pilings. An illustration of nature conforming to our presence on the water and what we deem to be acceptable for our environment.

But, humankind must sometimes accept and conform to nature. The fishermen of Uganik Bay have built their fishing camps above the tidal line and strung out their nets where the fish traditionally run. Most of the men and women who live here have chosen to do so because this is where the fish are found. One such gentlemen is Toby Sullivan, a commercial fisherman, who in 1975 headed to Alaska from Connecticut to work on the Alaskan pipeline. Instead, he found himself fishing vs. working on the pipeline and to this day is still gill-netting salmon to make a living. Toby’s fishing camp, East Point, located on the south shore of the Uganik Bay, has had a net on the site for the past 80 years. And, unfortunately, we drifted into that site when a strong current took us by surprise while we were gathering water quality data over the side of the small sonar vessel. When this happened, Toby and his crew worked swiftly and diligently to secure their fishing gear while NOAA divers were summoned from the Rainier to safely help our vessel leave the area.

A few evenings later, Mr. Sullivan and his crew came on board the Rainier as dinner guests and a rich discussion of hydrographic work and fishing gear followed. He explained in detail how he sets his fishing gear and offered the idea that a radio channel be utilized between NOAA’s small vessels that are working around fishing gear and the local fisherman, in order to facilitate better communication.

As I watched the exchange of ideas between Commanding Officer E.J. Van Den Ameele and Mr. Sullivan it appeared that both men recognized that both parties were interested in Uganik Bay because the ocean and humans are inextricably interconnected. The Rainier’s primary mission in Uganik Bay is to gather the necessary data to create accurate and detailed charts for navigational use by the local fisherman and other mariners. As a commercial fisherman, Mr. Sullivan’s primary interest is to keep his gear and crew safe while continuing to make a living from the harvest of local fish.

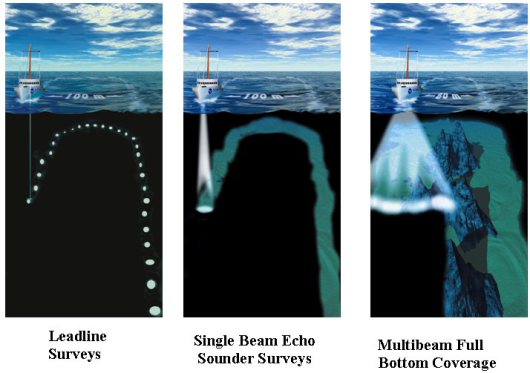

Today the Rainier continues on with its mission of hydrographic work at sea using the multibeam sonar which is located on the hull of the Rainier. The swath that multibeam sonar on the Rainier covers is similar to the swath of the multibeam sonar on the smaller boats; the coverage area depends on the depth of the water. For example, at our current water depth of 226 meters, the swath of each pass that the multibeam sonar makes an image of is 915 meters wide. This evening, upon the completion of the work with the Rainier’s multibeam sonar we will depart the area and be underway for Kodiak, AK.

All Aboard!

Michael Bloom serves as as survey technician aboard the Rainier and kindly took some time with me to discuss his background and work aboard the Rainier.

Tell us a little about yourself:

I grew up in a military family, so I was actually born in England and have lived in Florida, Nebraska, Montana, Oregon and Washington. I went to college at Oregon State University located in Corvallis, OR and majored in earth systems with a focus on marine science.

How did you discover NOAA?:

Ever since I was a little kid instead of having posters of bands etc… I had posters of maps. NOAA Corps participated in career fairs at my university. I stopped at their booth my sophomore year and again my junior and senior year to learn more about their program. After learning more about NOAA I also focused on the marine aspect of earth science because I knew I wanted to work with them. Initially I didn’t know about the civilian side of NOAA, so I applied for the NOAA Corps two times and wasn’t accepted into the program, although I was an alternate candidate once. At some point, when speaking with an officer he told me to apply for a civilian position with NOAA. So, I applied and was accepted.

I’m happy to be on the civilian side because I get to work on the science side of the operations all of the time and I get to keep my beard!

What are your primary responsibilities when working on the ship?:

I am survey tech and my primary duties include data acquisition and data processing. We can work to become the Hydrographer in Charge on the surveys after enough time working in the field and, if after the Field Operations Officer observes us, he feels confident that we are ready. Eventually I’d like to work for NOAA as a physical scientist, a job that would have me going out to sea several times a year but one that is primarily land based.

What do you love about your work with NOAA?:

I get paid to travel! I go to places that people pay thousands of dollars to visit and I actually get paid thousands of dollars to go there. I enjoy that I can see the real world application of the work that I do. Scientists are using our data and ultimately we could be saving lives by creating such accurate charts.

Personal Log

NOAA’s website for the Rainier states that the Rainier is one of the most productive and advanced hydrographic ships in the world. After spending two weeks working on board the Rainier, I couldn’t agree more. However, I don’t believe that it is only the cutting-edge technology that makes the Rainier one of the best hydrographic ships in the fleet. But rather a group of outstanding people at the helm of each of the different technical aspects of hydrography. Hydrographic surveying has many steps before the end product, a chart, is released. The people I met on board who are part of that process are teaching each other the subtle nuances of Rainier’s hydrographic mission in order to become even better at what they do. I am grateful for the time that the crew and Officers have graciously given me while I have been on board. I felt very welcome from the moment a NOAA Corps member picked me up at the airport throughout my stay on the Rainier as I continued to pepper everybody with questions. Thank you Rainier! I am confident that when I return to my classroom your efforts to help me better understand your work of hydrographic surveying will pay off. You have given me the gift of new knowledge that, when shared with my students has the potential to ignite in them the same excitement and passion for science that so many of you possess.