NOAA Teacher at Sea Virginia Warren

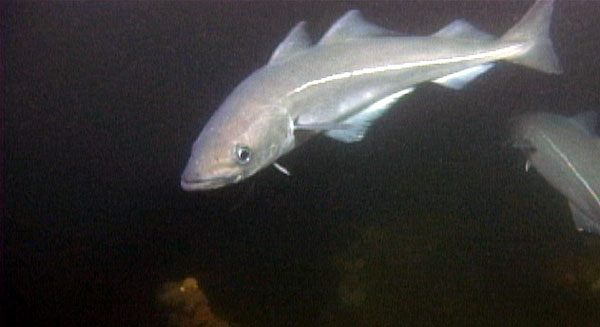

Mission: Acoustic and Trawl Survey of Walleye Pollock

Geographical Area of Cruise: Shelikof Strait

on NOAA ship Oscar Dyson

Date: 3/20/16 – 3/22/16

Data from the Bridge (3/21/16):

Sky: Snow

Visibility: 8 to 10 nautical miles (at one point it was more like 2 to 3 nautical miles)

Wind Speed: 23 knots

Sea Wave Height: 4 – 6 feet

Sea Water Temperature: 5° C (41°)

Air Temperature: 0° C (32° F)

Barometric (Air) Pressure: 994.3 Millibars

Science and Technology Log:

The purpose of this research survey is to collect data on walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus) that scientists will use when the survey is complete to help determine the population of the pollock. This data also helps scientists decide where and when to open the pollock fishery to fishermen. Data collection such as this survey are critical to the survival and health of the pollock fishery.

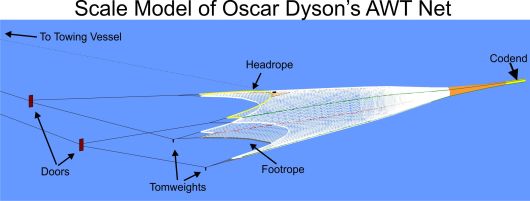

As I mentioned in a previous blog post, we use an AWT (Aleutian Wing Trawl) to complete the pollock survey. The AWT has two doors that glide through the water and hold the net open. The cod end of the net is where all of the fish end up when the trawl is complete.

Scale model of the Aleutian Wing Trawl (AWT) net courtesy of NOAA Scientist Kresimir Williams (Source: TAS Melissa George)

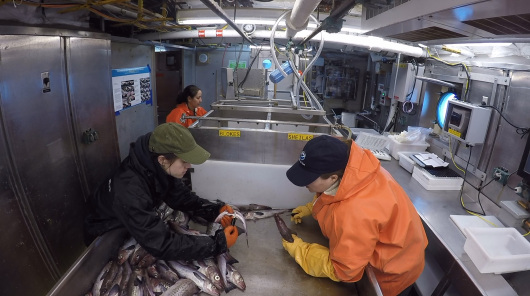

After the trawl is brought back onto the boat, the cod end of net is dumped onto a hydraulic table. The hydraulic table is then lifted up so that it angles the fish down a shoot into the Wet Lab on a conveyor belt.

Once the pollock come through the shoot and onto the conveyor belt, the first thing that we do is pick out every type of animal that is not a pollock. So far we have found lots of eulachons (Thaleichthys pacificus), jellyfish (Cnidaria), isopods, and squid. We have even found the occasional chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), rock fish (Sebastes spp.), and a lumpsucker (Cyclopteridea). The pollock continue to roll down the conveyor belt into a plastic bin until the bin is full. Then the bin of pollock are weighed.

Contents of the Trawl

The data from every fish we sample goes into a computer system called CLAMS. CLAMS stands for Catch Logger for Acoustic Midwater Survey. While we are taking samples of the fish our gloves get covered in fish scales and become slimy, so to be able to enter the data into the CLAMS system without causing damage there is a touch screen on all of the computers in the Wet Lab.

CLAMS computer system with a touch screen.

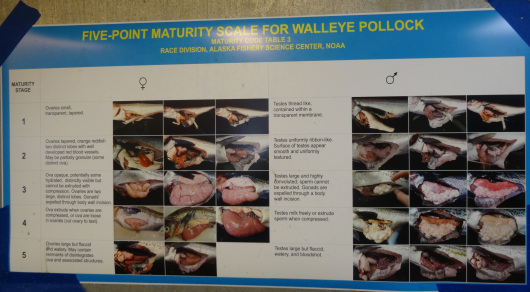

Once the pollock are weighed, a sample of the fish are taken to be sexed. To sex the fish, we use a scalpel to slice into the side of the fish. The picture of the chart below shows what we are looking for to determine if a pollock is male or female. Once we know what sex the fish is, we put it into a bin that says “Sheilas” for the female fish and “Blokes” for the male fish.

This chart of the Maturity Scale for Walleye Pollock is hanging in the Wet Lab.

Up-close of the Maturity Scale for female pollock.

Up-close of the Maturity Scale for male pollock.

Kim showing Virginia what to look for when sexing the fish.

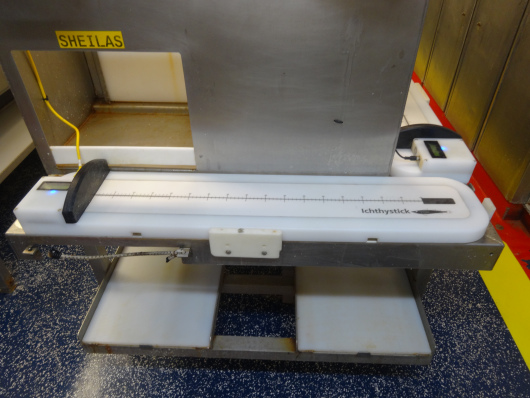

Once the fish are in their correct male/female bin, they are then measured for their length using an Ichthystick.

The Ichtystick was designed and built by MACE staff Rick Towler and Kresimir Williams who wrote a paper on it: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165783610001517

The Ichthystick has a magnet under the board. When the fish is placed on top of the board, a hand held magnet is placed at the fork of the fish tale. Where the hand held magnet is attracted to the magnet under the board tells the computer the length of the fish and the data is automatically stored in the CLAMS program.

Ichtystick

Getting the length of the starry flounder using the Ichthystick.

The next station is where the stomach, ovaries, and otoliths are removed from the fish and preserved for scientists to research when the survey is over. The ovaries of a female fish are weighed as well. Depending on the size of the ovaries, they may be collected for further research. Once all of the data has been collected from the fish, a label is printed with the data on it. This label is placed in the bag with the stomach or ovaries sample. Kim completes a special project for this survey. She is a stomach content analysist, so she collects stomachs from a sample of fish that will be taken back to her lab to analyze the stomach content of what she collected. She puts the stomach and the label with the fish’s information, into a bag that is placed in a solution of formalin that preserves the samples.

The next step is to get the otoliths out of the fish. A knife is used to cut across the head of the pollock. Otoliths are used to learn the age of the fish. The otoliths are placed in a glass vile that has a barcode number that can be scanned and put with all of the fish’s information in CLAMS. This number is used to keep track of the fish data for when the otoliths get analyzed later on.

Getting the Otoliths

We also collect length, weight, sex, and stomach samples from other fish that come up in the trawl as well.

Interview with a NOAA Corps Officer: Ensign Caroline Wilkinson

Caroline is a Junior NOAA Corps Officer on board the NOAA ship Oscar Dyson. She is always very helpful with any information asked of her and always has a smile on her face when she does so. Thank you Caroline for making me feel so welcomed on board the Dyson!

Ensign Caroline Wilkinson

How did you come to be in NOAA Corps? (or what made you decide to join NOAA Corps and not another military branch?

- I graduated from college in May of 2015. I was looking for a job at a career fair at my school and discovered the NOAA Corps. I had heard of NOAA, but didn’t know a lot about NOAA Corps. I wanted to travel and NOAA Corps allowed me that opportunity. I was unsure what type of work I wanted to do, so I decided to join and explore career options or make a career out of NOAA Corps.

What is your educational/working background?

- I went to the University of Michigan where I received an undergraduate degree in ecology and evolutionary biology and a minor in physical oceanography.

How long have you been in NOAA Corps?

- July of 2015 I started basic training. Training was at the Coast Guard academy in a strict military environment. We had navigation and ship handling classes seven hours a day.

How long have you been on the Dyson?

- I have been here since December of 2015.

How long do you usually stay onboard the ship before going home?

- We stay at sea for two years and then in a land assignment for 3 years before heading back to sea.

Have you worked on any other NOAA ships? If so, which one and how long did you work on it?

- Nope, no other ships. I had no underway experience except a five-day dive trip in Australia.

Where have you traveled to with your job?

- We were in Newport, Oregon and then we went to Seattle, Washington for a couple of weeks. Then we went to Kodiak and then to Dutch Harbor.

What is your job description on the Dyson?

- I’m a Junior Officer, the Medical Officer, and the Environmental Compliance Officer. As a junior officer I am responsible for standing bridge watch while underway. As a Junior Officer I am responsible for standing 8 hours of watch, driving the ship, every day. As medical officer, we have over 150 drugs onboard that I am responsible for inventorying, administering, and ordering. I also perform weekly health and sanitary inspections and Weekly environmental walkthroughs where I’m looking for any safety hazards, unsecured items, leaks or spills that could go into the water.

What is the best part of your job?

- Getting to drive the ship.

What is the most difficult part of your job?

- Being so far away from my family and friends.

Do you have any career highlights or something that stands out in your mind that is exceptionally interesting?

- During training we got to sail in the US Coast Guard Cutter Eagle. It’s a tall ship (like a pirate ship). We were out for eight days. We went from Baltimore to Port Smith, Virginia and had the opportunity to do a swim call 200 miles out in the Atlantic.

What kind of sea creature do you most like to see while you are at sea?

- We have seen some killer whales and humpback whale in the bay we are in this morning. We’ve also seen some albatross.

Do you have any advice for students who want to join NOAA Corps?

- You need an undergraduate degree in math or science. There are 2 classes of ten students a year. Recruiters look for students with research experience, a willingness to learn, and a sense of adventure.

Ensign Caroline Wilkinson at the helm.

Personal Log:

I have really been enjoying my time aboard the Oscar Dyson and getting to know the people who are on the ship with me. I love spending time on the Bridge because you can look out and see all around the ship. I also like being on the bridge because I get to witness, and sometimes be a part of, the interactions and camaraderie between the NOAA Corps Officers that drive/control the ship and the other ship workers.

Panoramic view of the NOAA Ship Oscar Dyson‘s Bridge. Look at all of those windows!

Arnold and Kimrie are responsible for making breakfast, lunch, and dinner for all 34 people on the Oscar Dyson. They also clean the galley and all of the dishes that go along with feeding all of those people. They probably have the most important job on the ship, because in my previous experiences, hungry people tend to be grouchy people.

Arnold and Kimrie are the stewards of the Oscar Dyson.

We’ve had a variety of yummy dishes made for us while we’ve been at sea. Breakfast starts at 7 a.m. and could include a combination of scrambled eggs, breakfast casserole, French toast, waffles, chocolate pancakes, bacon, sausage, or my personal favorite, eggs benedict.

Breakfast is served. YUM!!!

Lunch is served at 11 a.m. and seems like a dinner with all of the variety of choices. Lunch usually has some type of soup, fish, and another meat choice available, along with vegetables, bread, and desert. Dinner is served at 5 p.m. and usually soup, fish, and another meat choice available, along with vegetables, bread and desert. I loved getting to try all of the different types of fish that they fix for us and I also really liked getting to try Alaskan King Crab for the first time!!

If you are still hungry after all of that, then there is always a 24-hour salad bar, a variety of cereal, snacks, and ice cream available in the galley. The left-overs from previous meals are also saved and put in the refrigerator for anyone to consume when they feel the need. If we are working and unable to get to the galley before a meal is over, Arnold or Kimrie will save a plate for us to eat when we get finished.

I also tried Ube ice cream, which is purple and made from yams. At first I was very skeptical of any kind of sweet treat being made out of yams, but I was pleasantly surprised that it tasted really good!

Ube ice cream made from yams! Very YUMMY!!!

There is even a place to do laundry on this ship, which I was very happy about because fishy clothes can get pretty stinky!

Laundry Room

I can’t end a blog without showing off some of the beautiful scenery that I have been privileged to see on this journey. The pictures below are of the Semidi Islands.