NOAA Teacher at Sea

David Walker

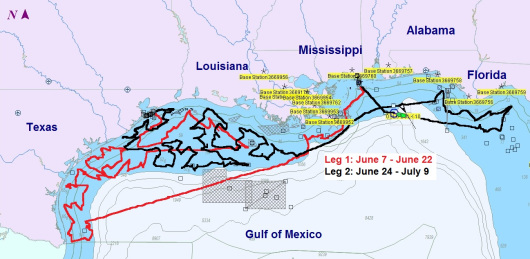

Aboard NOAA Ship Oregon II

June 24 – July 9, 2015

Mission: SEAMAP Bottomfish Survey

Geographical Area of Cruise: Gulf of Mexico

Date: July 8, 2015

Weather Data from the Bridge

NOAA Ship Oregon II Weather Log 7/7/15

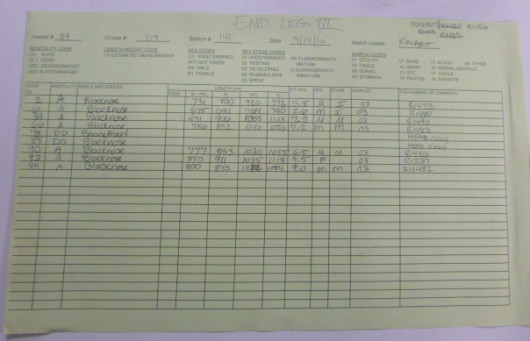

The seas have remained incredibly calm, again with waves normally no higher than 1 ft. July 7, 2015 was a beautiful day, with few (FEW, 1-2 oktas) clouds in the sky (see above weather log from the bridge). Visibility from the bridge was 10 nautical miles (nm) throughout the day.

Science and Technology Log

After a run of around 16 hours, we finally arrived on the west coast of Florida to continue the survey.

-

-

Near the Mississippi River delta on Day 12, setting sail for Florida

-

-

Sunrise on Day 13 near the northern coast of Florida

Wow! The organisms caught on the west coast of Florida were entirely different from those caught west of the Mississippi. In our first trawl catch, I almost didn’t recognize a single species.

Fisheries biologist Kevin Rademacher shared with me an article, “Evidence of multiple vicariance in a marine suture-zone in the Gulf of Mexico” (Portnoy and Gold, 2012), that offers a potential explanation for the many differences observed. The paper is based on what are called “suture-zones.” A suture-zone, as defined previously in the literature, is “a band of geographic overlap between major biotic assemblages, including pairs of species or semispecies which hybridize in the zone” (Remington, 1968). In other words, it is a barrier zone of some kind, allowing for allopatric speciation, yet also containing overlap for species hybridization. As noted by Hobbes, et al. (2009), such suture-zones are more difficult to detect in marine environments, and accordingly, have received less attention in the literature. Such zones, however, have been discovered and described in the northern Gulf of Mexico, between Texas and Florida (Dahlberg, 1970; McClure and McEachran, 1992).

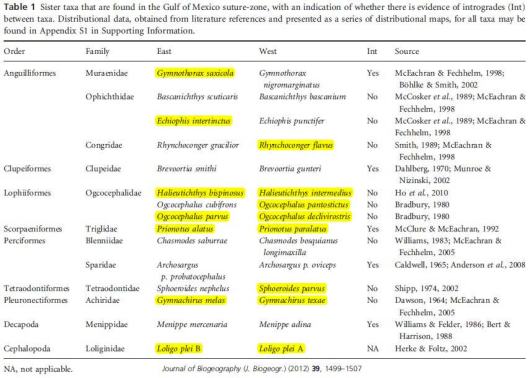

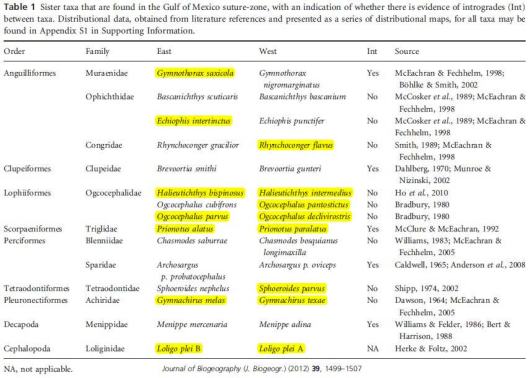

Portnoy and Gold note that “at least 15 pairs of fishes and invertebrates described as ‘sister taxa’ (species, subspecies, or genetically distinct populations) meet in this region, with evidence of hybridization occurring between several of the taxa” (Portnoy and Gold, 2012). The below table delineates these sister taxa. On this table, I have highlighted species that we have found on this survey.

Sister taxa found in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Highlighted are species we have encountered on this survey (Portnoy and Gold, 2012).

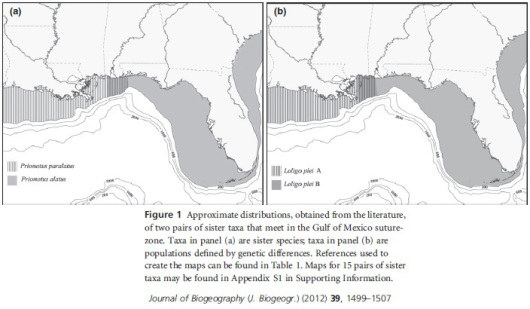

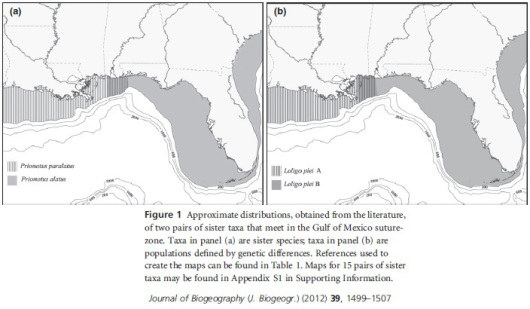

The figure below geographically illustrates distribution patterns of two pairs of sister species within the northern Gulf of Mexico. We have seen all four of these species on this survey, and our observations have been consistent with these distribution patterns.

Distributions of “sister taxa” within the northern Gulf of Mexico (Portnoy and Gold, 2012)

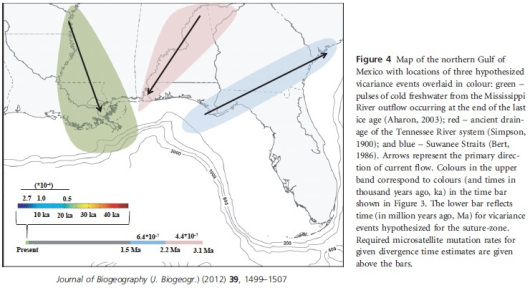

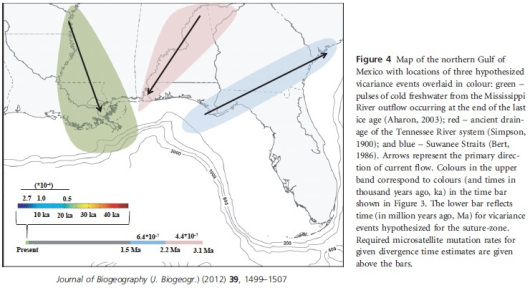

Prior to Portnoy and Gold, hypothesized reasons for the suture-zone and allopatric speciation in the northern Gulf included “(1) a physical barrier, similar to the Florida peninsula, that arose c. 2.5 million years ago (Ma) during the Pliocene (Ginsburg, 1952), (2) an ecological barrier, perhaps a river that drained the Tennessee River basin directly into the Gulf, that existed approximately 2.4 Ma (Simpson, 1900; Ginsburg, 1952), (3) a strong current that flowed from the Gulf to the Atlantic through the Suwanee Straits approximately 1.75 Ma (Bert, 1986), and (4) extended cooling during early Pleistocene glaciations occurring c. 700–135 thousand years ago (ka) (Dahlberg, 1970)” (Portnoy and Gold, 2012). Another explanation has been offered by Hewitt (1996), involving marine species being forced into different areas of refuge during the glacial events of the Pleistocene, allowing for allopatric speciation. Following the retreat of the glaciers, according to this hypothesis, these species would have been allowed to come into contact again, allowing for hybridization.

Portnoy and Gold used mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA sequence data from Karlsson et al. (2009) to “determine if estimated divergence times in lane snapper were consistent with the timing of [the above] hypothesized variance events in the suture-zone area, in order to distinguish whether the Gulf suture-zone is characterized by a single or multiple vicariance event(s)” (Portnoy and Gold, 2012).

Their results suggest that the divergence of lane snapper in the northern Gulf occurred much more recently than the hypothesized events described by Ginsberg (1952), Bert (1970), and Dahlberg (1970). These results also suggest that the explanation offered by Hewitt (1996) is an unlikely explanation for the divergence of lane snapper, for even though the time of multiple glaciations is consistent with the time of lane snapper divergence, water temperatures across the Gulf are estimated to have been within the thermal tolerance of lane snapper during these glaciations. Evidence also suggests that a shallow shelf existed during these glaciations, representing a habitat in which lane snapper could have lived.

The explanation that Portnoy and Gold favor, in terms of explaining lane snapper divergence, is one suggested by Kennett and Shackleton (1975), as well as by Aharon (2003). This explanation involves “large pulses of freshwater from the Mississippi River caused by a recession of the Laurentide Ice Sheet between 16 and 9 ka” (Portnoy and Gold, 2012). This explanation would have also allowed for potential sympatric or parapatric speciation, because it contains multiple lane snapper habitat types (carbonate sediment, as well as mud and silt bottom).

Notably, the fact that the above explanation is favored by Portnoy and Gold for lane snapper divergence does not discount the explanations of Ginsberg (1952), Bert (1970), Dahlberg (1970), and Hewitt (1996), in terms of explaining the many other examples of species divergence exhibited within the northern Gulf. It is most probable that many geological and ecological causes worked, sometimes in confluence, to create the divergences and hybridizations in species observed today. A geographical depiction of many of the hypothesized explanations described by Portnoy and Gold is below.

Geographical depiction of hypothesized triggers of species divergence in the northern Gulf of Mexico (Portnoy and Gold, 2012)

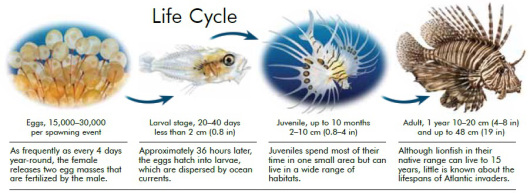

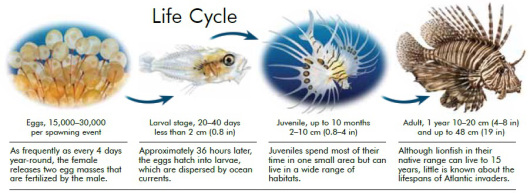

In addition to the species divergence observed in our survey, another interesting difference noted in our catches along the western coast of Florida was the emergence of lionfish. These invasive species are native to the Indian Ocean and southwest Pacific Ocean, and they were most likely introduced by humans into the waters surrounding Florida. There are two lionfish species that are invasive in Florida, P. miles and P. volitans (Morris, Jr. et al., 2008), and the earliest records of their introduction into Florida’s waters are from 1992 (Morris, Jr. et al., 2008). Many characteristics have allowed these species to be successful alien invaders in these waters – (1) they are formidable, with venomous spines and an intimidating appearance, (2) they reproduce incredibly quickly, breed year-round, and mature at a young age, (3) they outcompete native predators for food and habitat, (4) they are indiscriminate feeders with voracious appetites, and (5) they take advantage of a sea that is over-fished, in which many of their predators are regularly being eliminated by humans (Witherington, 2012).

Life cycle of the lionfish

This invasion mechanism hauntingly reminds me of that of the Cane Toad, a very famous alien invader which has decimated the flora and fauna of Australia. One of the main worrisome effects of lionfish around Florida is on coral reefs. Lionfish “can reduce populations of juvenile and small fish on coral reefs by up to 90 percent…[and] may indirectly affect corals by overconsuming grazing parrotfishes, which normally prevent algae from growing over corals” (Witherington, 2012).

-

-

Areas affected by the invasive lionfish

-

-

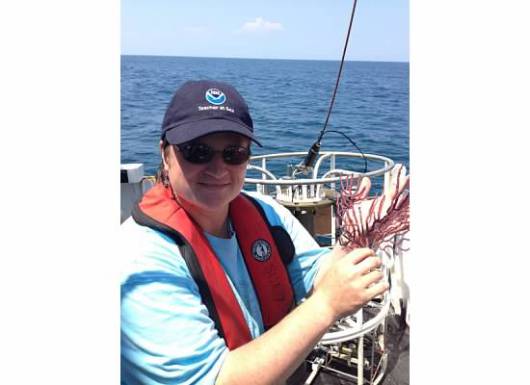

One of the larger lionfish (Pterios spp.) caught on Day 13

One of the ways in which Floridians are trying to eliminate this problem is through lionfish hunting tournaments. CJ Duffie, a volunteer on this survey from Florida, has participated in these tournaments and also participates in lionfish research directed by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. CJ harvested the gonads of the lionfish we caught on Day 13 to take back to the lab for further analysis. Floridians also actively promote the lionfish as a delicacy, in an attempt to encourage more people to eat the invasive species. CJ described the fish as the best he has ever tried, so I was very easily intrigued. A fillet was prepared from the large lionfish caught on Day 13 fish, and Second Cook (2C) Lydell Reed was able to cook it on the spot. I agree with CJ – white, flakey, slightly sweet, this is the best fish I have ever tasted.

-

-

Volunteer CJ Duffie, removing the gonads of a lionfish

-

-

Lionfish gonads

-

-

Filleting a larger lionfish

-

-

Lionfish fillet

Personal Log

The survey is nearly over, and this will be my last post. We are in transit back to Pascagoula, Mississippi, the ship’s home port. I leave by plane from Mobile, Alabama for Austin on Friday, July 10, 2015. I am eagerly anticipating walking on land, as I’ve heard it’s strange at first after being on a boat for awhile. Apparently this weird feeling has a semi-formal name — “dock rock”.

This experience has truly been one of the best of my life, especially in terms of the raw amount I have learned every day. Coming in, the sole knowledge of fish life I had derived from my stints fly fishing with my father, and most of this knowledge concerns freshwater fish. I now feel as though I have a much more comprehensive knowledge of the biodiversity that exists in the Gulf of Mexico and a much greater appreciation for the diversity of life as a whole. I have taken over 200 photos to document this biodiversity, accumulated a diverse collection of preserved specimens, and collected a wide variety of resources (textbooks, scientific papers, etc.) on marine life in the Gulf of Mexico. These resources will surely make the preparation of a project-based activity for my students focused on this research a much easier feat.

Having fun with a sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates) during analysis of the last trawl catch

I have also learned how a large portion of marine field research is conducted. We have surveyed dissolved oxygen levels in the water, plankton biodiversity, and bottomfish biodiversity throughout the northern Gulf, using established (and quite popular) research methods. The knowledge I have gained here can be applied to the biodiversity project portion of my geobiology class, in which students conduct biodiversity surveys in local Austin-area parks and preserves. I anxiously await the comprehensive results of this summer’s NOAA survey – the complete dissolved oxygen contour map, the biodiversity indexes for different regions of the Gulf, and plankton biodiversity data from Poland. These data will definitely help me come to even more conclusions about the marine life in the Gulf and the factors affecting it.

Through this experience, I have also gained much appreciation for the diversity of careers that exist on board a NOAA research vessel. I have learned about the great work of the NOAA Corps, a Commissioned Service of the United States. I have learned from the fisherman, engineers, stewards, and other personnel on the boat, all required for a successful research survey.

First and foremost, I have to thank the science team on the night watch – fisheries biologists Kevin Rademacher and Alonzo Hamilton, FMES Warren Brown, and volunteer CJ Duffie. These individuals were instrumental in helping me identify organisms, label my photos, and craft my blog posts and photo captions. Kevin Rademacher provided me with most of the papers which I have referenced in this blog, and with no internet connectivity on the boat for around half of the trip, his library of information was essential. For the “Notable Species Seen” section of this blog, Kevin also individually went through all of my species photos with me to help me add common and scientific names in the photo captions. This took a great deal of his time, almost every day, and I am incredibly appreciative.

The rest of the night watch. From left to right — FMES Warren Brown and NOAA Fisheries Biologists Kevin Rademacher and Alonzo Hamilton

I also definitely need to thank Lead Fisherman Chris Nichols and Skilled Fisherman Chuck Godwin for their mentorship with CTD data collection and plankton sampling. In addition, many thanks to Field Party Chief Andre Debose and Lieutenant Commander Eric Johnson for proofreading my blog entries and ensuring that my experience on the ship was a good one. I enjoy learning from people much more than I enjoy learning from books, and these have been some of best (and most patient) teachers I have ever had.

Lastly, thanks so much to the NOAA Teacher at Sea staff for your work on this great program. It truly makes a difference for many teachers and many students. I have had an amazing time, and I am positive my students will benefit from what I have learned.

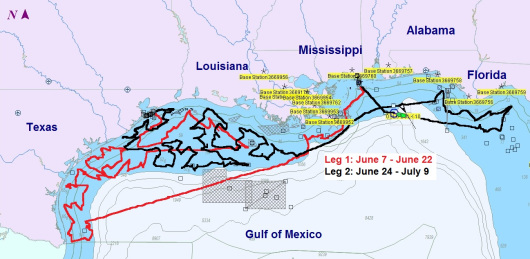

The ship’s path during the survey, thus far. I have been on the boat for Leg 2, drawn in black.

Did You Know?

Lionfish venom is not contained within the tips of the fish’s spines. Rather, glandular venom-producing tissue is located in two grooves that run the length of each spine. When skin is punctured by a spine, this glandular tissue releases the venom (a neurotoxin), which travels up the spine and into the wound by means of the grooves (Witherington, 2012).

Anatomy of the lionfish spine

Notable Species Seen

-

-

Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus)

-

-

Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus)

-

-

Sea Star (Goniaster tessellatus)

-

-

Cushion Sea Star (Oreaster grandis)

-

-

Lined Sea Star (Luidia clathrata)

-

-

Banded Sea Star (Luidia alternata)

-

-

Pencil Urchin (Stylocidaris affinis)

-

-

Spotfin Butterflyfish (Chaetodon ocellatus)

-

-

Bank Sea Bass (Centropristis ocyurus)

-

-

Fringed Filefish (Monacanthus ciliatus)

-

-

Gray Triggerfish (Balistes capriscus)

-

-

Horned Searobin (Bellator militaris)

-

-

Lancer Stargazer (Kathetostoma albigutta)

-

-

Barbfish (Scorpaena brasiliensis)

-

-

Longfin Scorpionfish (Scorpaena agassizii)

-

-

Lionfish (Pterios spp.)

-

-

Lionfish (Pterios spp.)

-

-

Bigeye Searobin (Prionotus longispinosus

-

-

Blue Angelfish (Holacanthus bermudensis)

-

-

Dusky Flounder (Syacium papillosum)

-

-

Bluespotted Searobin (Prionotus roseus)

-

-

A Chace Slipper Lobster (Scyllarus chacei), doing handstand pushups

-

-

Clearnose Skate (Raja eglanteria)

-

-

Honeycomb Moray (Gymnothorax saxicola)

-

-

Honeycomb Moray (Gymnothorax saxicola)

-

-

Spotted Spoon-Nose Eel (Echiophis intertinctus)

-

-

Spotted Spoon-Nose Eel (Echiophis intertinctus)

-

-

Marbled Puffer (Sphoeroides Dorsalis)

-

-

Sooty Seahare (Aplysia morio)

-

-

Sooty Seahare (Aplysia morio), swimming underwater

-

-

Red Goatfish (Mullus auratus)

-

-

Roughback Batfish (Ogcocephalus parvus)

-

-

Sargassumfish (Histrio histrio)

-

-

Sharpnose Puffer (Canthigaster rostrata)

-

-

Sponge (Demospongiae)

-

-

Sponge (Demospongiae)

-

-

Sponge (Demospongiae)

-

-

Sponge (Demospongiae)

-

-

Sponge (Demospongiae)

-

-

Snakefish (Trachinocephalus myops)

-

-

Shrimp Flounder (Gastropsetta frontalis)

-

-

Striped Burrfish (Chilomycterus schoepfii)

-

-

Tattler (Serranus phoebe)

-

-

Variegated Urchin (Lytechinus variegatus)

-

-

Atlantic Guitarfish (Rhinobatos lentiginosus)

-

-

Jackknife-Fish (Equetus lanceolatus)

-

-

Hogfish (Lachnolaimus maximus)

-

-

Hidalgo’s Murex (Murexiella hidalgoi)

-

-

Hidalgo’s Murex (Murexiella hidalgoi)

-

-

Hairy Sponge Crab (Cryptodromiopsis antillensis)

-

-

Cubbyu (Paraques umbrosus)

-

-

Blue-Eye Hermit (Paguristes sericeus) in shell

-

-

Blue-Eye Hermit (Paguristes sericeus) out of shell

-

-

Leopard Searobin (Prionotus scitulus)

-

-

Littlehead Porgy (Calamus proridens)

-

-

Longlure Frogfish (Anternnarius multiocellatus)

-

-

Nodose Box Crab (Calappa tortugae)

-

-

Polka-Dot Batfish (Ogcocephalus cubifrons)

-

-

Unicorn Filefish (Aluterus monoceros)

-

-

Twospot Flounder (Bothus robinsi)

-

-

Twospot Cardinalfish (Apogon pseudomaculatus)

-

-

Sponge Cardinalfish (Phaeoptyx xenus)

-

-

Scrawled Filefish (Aluterus scriptus)

-

-

Sea Star (Echinaster serpentarius)

-

-

Sea Cucumber (Holothuriidae)

-

-

Scrawled Cowfish (Acanthostracion quadricornis)

-

-

Scrawled Cowfish (Acanthostracion quadricornis)

-

-

Short Bigeye (Pristigenys alta)

-

-

Round Scad (Decapterus punctatus)

-

-

Bigtooth Cardinalfish (Apogon affinis)

-

-

Dwarf Humpback Shrimp (Solenocera atlantidis)

-

-

Longnose Batfish (Ogcocephalus corniger)

-

-

Vermilion Snapper (Rhomboplites aurorubens)

-

-

Yellowline Arrow Crab (Stenorhynchus seticornis)

-

-

Unidentified Crab #1 – taken back to lab for further analysis

-

-

Unidentified Crab #2 – taken back to lab for further analysis

-

-

Unidentified Crab #3 – taken back to lab for further analysis

-

-

Unidentified Crab #4 – taken back to lab for further analysis

-

-

A laughing gull dives for some of the fish jettisoned after completion of the analysis of the catch.

Newest addition to our family: Paavo a Finnish Lapphund Photo Credit: Lynn Drumm,

Newest addition to our family: Paavo a Finnish Lapphund Photo Credit: Lynn Drumm,