EPA’s MESA Air Study Confirms that Air Pollution Contributes to the #1 Cause of Death in the U.S.

By Dr. Wayne Cascio

This week we took a giant leap forward in our understanding of the relationship between air pollution and heart disease with the publication of results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Air Pollution Study (MESA Air) in the leading medical journal The Lancet.

For more than two decades, scientific evidence has shown fine particle pollution (PM2.5) in the outside air is a cause of cardiovascular illness and death, and has justified improving the PM2.5 annual National Ambient Air Quality Standard to protect public health. Yet, MESA Air was the first U.S. research study to examine a group of people over a period of 10 years and measured directly how long-term exposure to air pollution contributes to the development of heart disease and can lead to heart attacks, abnormal heart rhythms, heart failure, and death. MESA Air did just that, and Dr. Joel Kaufman, the leader of MESA Air at the University of Washington and his colleagues should be commended for their accomplishment.

MESA Air was funded by EPA and made possible by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which supports a larger study on atherosclerosis called MESA. The additional air pollution study had the ambitious goal of seeking an answer to the question of whether long-term exposure to PM2.5 and nitrogen oxides (NOx) was associated with the development and progression of cardiovascular disease. A total of 6,800 people with diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds and residing in six locations throughout the country agreed to participate in the decade-long study by researchers at the University of Washington who received the grant. And the results are in!

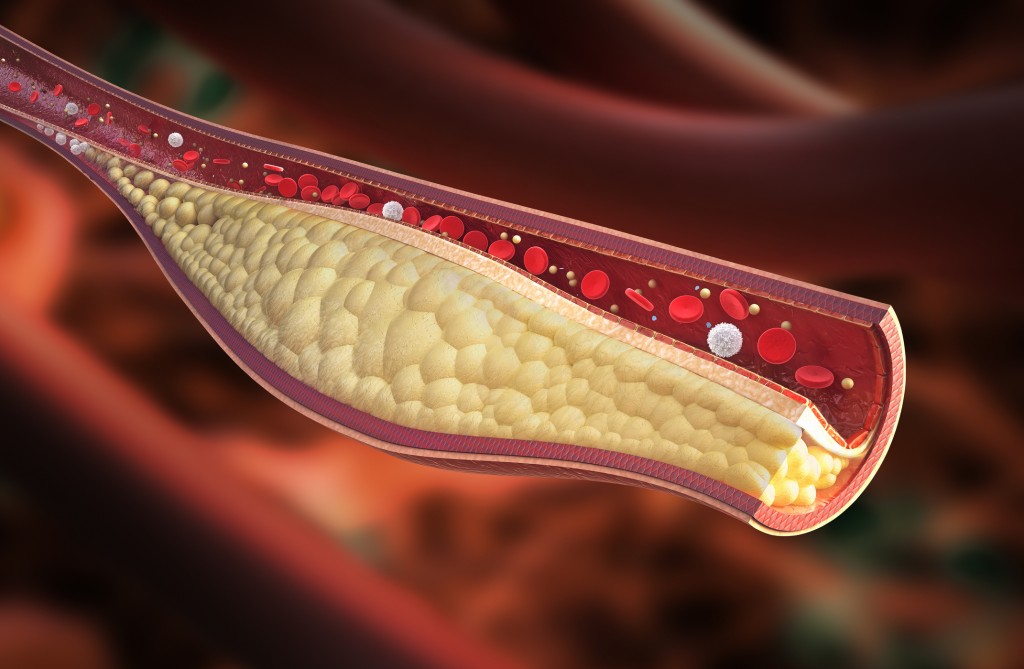

The researchers used computerized tomography imaging to measure coronary artery calcium content in the same person repeatedly during the study as an indication of coronary artery disease. The results showed that long-term exposure to PM2.5 and NOx increased coronary artery calcium. The increase observed is at a rate that, over the period of the study, would change the risk of heart attack in some.

This study is extraordinary in many ways. First it provides the strongest evidence yet that air pollution can and does contribute to cardiovascular disease–the number one killer of Americans and people in developed countries throughout the world. Secondly, the results define the relationship between air pollutants and the progression of coronary artery disease over time. This relationship will help estimate the long-term health impacts and economic burden of air pollution within our population. And, third the study shows the power of intra-agency cooperation to conduct valuable and cost-effective science.

The findings of MESA Air will continue to reverberate throughout the environmental science and public health communities for some time, but it’s time for healthcare providers, air quality managers and state and local planners to take note and to begin to consider long-term exposure to air pollution as having long-term health implications, even at levels near the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

About the Author: Dr. Wayne Cascio spent more than 25 years as a cardiologist before joining EPA’s Office of Research and Development where he now leads research on the links between exposures to air pollution and public health, and how people can use that information to maintain healthy hearts.

May 30, 2016 @ 09:52:12

Morning:

We are in city of Toronto, the largest city in Canada, a outdoor asphalt plant is adjacent to our property, and very closes to other neighbor buildings. Its machine just beside us and storage beside street where are bus stops. The dust and smoke, noise and vibration has affected too many people for 16 years, there are more than 25800 people within 1000m of it, and more than 2300 within 300m, including a senior home and long term care facility. People have health problem here, like throat sore, cough, hard to breathe and chest tightness…Some got asthma, some have heart disease…

I believe our area is good area for your study, long term — already 16 years, dense population area — big city center, unique — asphalt plant beside public without any separate distance, convenient — very closes to you.. Please study this case, you will get a lots of first hand data, rare opportunity for research. Please do not miss it.

Our community is Ward 12, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, our councillor, MPP and MP community offices (location 99 Ingram Drive) are all beside Ingram Asphalt Inc. (location 103 Ingram Drive), you will be very easy to find us. We are looking to hear from you soon.

Thank you for your time.