Conservation All Around Us: The Great Swamp

By Tina Wei

On June 9th, I assisted David Kluesner, EPA Region 2 community affairs team leader, at an event with the Great Swamp Watershed Association where he gave a presentation to the community members of Morristown, NJ about the significant steps the EPA is taking to clean up the lower Passaic River.

At the meeting, we heard attendees express strong support for activities to conserve the environment and protect human health. To learn about the community’s relationship with the environment and to see an example of successful, impactful conservation efforts, we visited the nearby Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge.

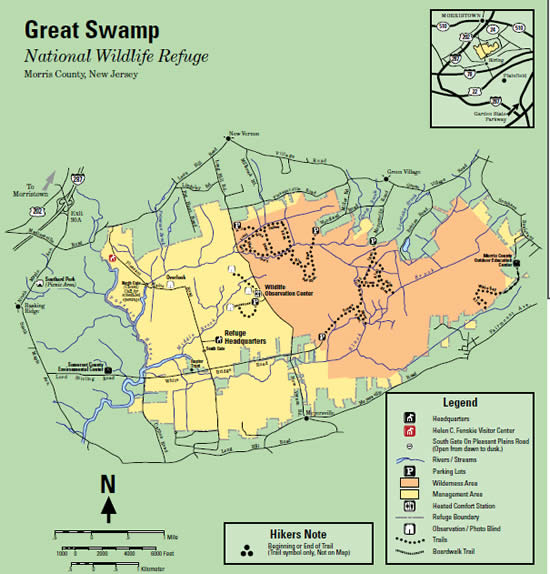

This refuge, established by Congress in 1960 and located in Morris County, NJ, is one of the 560 refuges in the Department of Interior’s U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s National Wildlife Refuge System. We toured the wonderful Helen C. Fenske Visitor Center, featuring interactive environmental education activities, friendly rangers, and live bird-cams. The refuge’s 7,768 acres of habitat allow for wildlife viewing, photography, and hunting.

We learned that North America is divided into four key flyways for migrating birds. New York City is located in the highly trafficked Atlantic Flyway. This refuge, located only 26 miles away from Times Square, is of great importance, providing a crucial resting place for over 244 species of birds who can’t rest in NYC.

Image by the the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

We also learned about this refuge’s unique history. Beginning in 1844, this area’s marshlands were drained and converted to agricultural fields. As these farms became unprofitable and disappeared, alternative uses for this land were proposed, including a 1959 proposal to turn this area into a major airport (what is now Newark Liberty International Airport). In response, community members raised more than one million dollars to buy almost 3,000 acres of the Great Swamp land, donating it to the Department of the Interior to be conserved and reverted back to swampland.

This history is interesting for thinking about key questions regarding conservation:

- When, why, and how should we conserve the environment?

- How can we understand our local histories in light of these questions?

Do you know about the local history of a National Wildlife Refuge? What do you think about conservation? Tell us in the comments section!

About the Author: Tina Wei is a summer intern in EPA’s Region 2 Public Affairs Division. She has loved this wonderful learning opportunity, and especially enjoys going on work-related fieldtrips. During the school year, she is an undergraduate student at Princeton University.