Creative Ways to Cut Your Holiday Waste

By Grace Doran and Jessica Kidwell

Between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day, American household waste increases by more than 25 percent. Trash cans full of holiday food waste, shopping bags, bows and ribbons, packaging, and wrapping paper contribute an additional 1 million tons a week to our landfills.

As we celebrate the holidays, it pays to be mindful of sustainable consumption and materials management practices. They may help you focus even more on caring and celebration during this holiday season, and could even reduce the strain on our fiscal budgets and the natural environment.

Giving

- Less is more. Choose items of value, purpose, and meaning – not destined for a yard sale.

- Give treasure. Pass on a favorite book, plant start, or antique. Check estate sales, flea markets, and resale shops for unique finds.

-

Give “anti-matter.” Focus on the experience, rather than wrapping and shipping. Share event tickets, museum memberships, gift certificates, or even your time and talents.

- Impart values, not wastefulness. Start a child’s savings account, or make a donation to a favorite charity in the recipient’s name.

- DIY. Handmade food and gifts display your creativity and demonstrate your dedication.

- Consider the source. Choose recycled or sustainably sourced materials. Shop local to support area shops, makers, and artisans while reducing shipping costs and impacts.

- Recharge. Consider rechargeable batteries (and chargers) with electronic gifts.

-

Use a reusable cloth bag for your purchases. Avoid bags altogether for small or oversized purchases.

- Plan ahead. Consolidate your shopping trips to save time, fuel, and aggravation. You’ll have more time for careful gift choices.

- Rethink the wrap. Reuse maps, comics, newsprint, kid art, or posters as gift wrap. Wrap gifts in recycled paper or a reusable bag. Or skip the gift wrap, hide the gifts, and leaves clues or trails for kids to follow.

Celebrating

- Trim the tree. Consider a potted tree that can be replanted, or a red cedar slated for removal during habitat/farm maintenance.

- Light right. Choose Energy Star energy-efficient lighting. LED outdoor holiday lights use 1/50th the electricity of conventional lights and last 20 to 30 years.

-

Make it last. Choose and reuse durable service items.

- Keep it simple. For larger gatherings, choose recyclable or compostable service items. All food-soiled paper products are commercially compostable, unless plastic- or foil-coated.

Looking Ahead

- Reduce. Donate outgrown clothes, old toys, and unwanted gifts.

- Reuse packing and shipping materials. Save ribbons, bows, boxes, bags, and décor for the next holiday.

- Recycle old electronics and batteries with an e-steward.

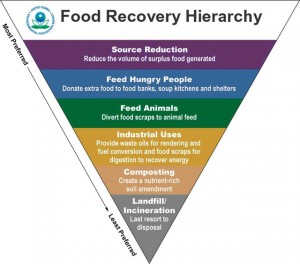

- Replant, mulch, or compost your live tree. Compost food scraps.

About the Co-Author: Grace Doran is a student intern in EPA Region 7’s Water, Wetlands and Pesticides Division. She is a senior at the University of Missouri-Columbia, studying civil engineering with an emphasis in environmental engineering. Grace has a passion for environmental education, listening to podcasts, running and pizza (and those don’t contradict each other).

About the Co-Author: Jessica Kidwell is a hydrogeologist with EPA Region 7’s Environmental Data and Assessment staff. She’s provided technical expertise and worked with stakeholders to advance scientific, environmental, and sustainability objectives for nearly 20 years.

is complex. One of its main components provides for states to monitor their waters to see whether these water bodies are meeting different designated uses. For example, if a stream is not swimmable, or has poor habitat for wildlife, the states pinpoint the lacking water-quality metrics, then come up with a plan to fix the problem, known as

is complex. One of its main components provides for states to monitor their waters to see whether these water bodies are meeting different designated uses. For example, if a stream is not swimmable, or has poor habitat for wildlife, the states pinpoint the lacking water-quality metrics, then come up with a plan to fix the problem, known as