EPA Science: Providing the Foundation for Environmental Justice

By Fred Hauchman and Andrew Geller

Yesterday, the Agency released the EJ 2020 Action Agenda, outlining our strategic plan to advance environmental justice for the next five years and set a course for greatly reducing or eliminating environmental health disparities for generations to come. The overall vision is to bring the promise of a clean, healthy, and more sustainable environment to everyone in the country, no matter where they live, work, play, or learn.

Yesterday, the Agency released the EJ 2020 Action Agenda, outlining our strategic plan to advance environmental justice for the next five years and set a course for greatly reducing or eliminating environmental health disparities for generations to come. The overall vision is to bring the promise of a clean, healthy, and more sustainable environment to everyone in the country, no matter where they live, work, play, or learn.

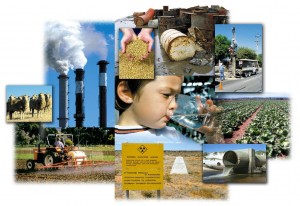

The plan recognizes that while we have made great progress improving the quality of air, water, and land over the past 40-plus years, there are far too many people who still face serious impacts and risks from exposures to environmental pollutants. We know that the people most affected are disproportionately from economically disadvantaged and minority communities. That’s not acceptable. As EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy has stated, “Everyone deserves to have their health protected from environmental exposures.”

As always, science is critical to making that health protection a reality. That’s why the EJ 2020 Action Agenda includes an explicit commitment by the Agency to conduct and support collaborative, community-based research. This approach is needed to not only better understand the complex, interrelated factors that lead to disproportionate environmental and related public health burdens, but to provide citizens with the information, data, and tools they need to fully participate in making the decisions that affect their communities and take action.

We will continue to develop and improve innovative decision support tools that help public health officials, citizen groups, researchers, and others identify and prioritize environmental concerns and assess cumulative impacts. This includes tools such as EnviroAtlas, the Community Cumulative Assessment Tool, and the recently released Community-Focused Exposure Risk and Screening Tool, (C-FERST). It also includes EPA’s Tribal Science effort, recognizing EPA’s responsibilities to America’s indigenous peoples and our shared role in building the capacity for the sovereign tribes to construct environmental programs that serve their nations. This suite of resources provides robust online mapping and visualization capabilities, extensive databases, case studies, and customizable applications.

Our researchers work closely with EPA’s Regions, local communities and stakeholder groups to continually improve and upgrade these and other EPA tools and resources, hold workshops and seminars, and solicit feedback. Such community engagement is key. Frequent, two-way communication with our community partners helps teams identify the highest priorities early. Together we can tailor research strategies that in the end will deliver the information and decision support needed to make lasting, visible local impact.

Another area where science and research are providing the foundation for actions to address environmental justice concerns is through the development of innovative environmental monitoring tools. Our researchers are helping usher in a new generation of low-cost, portable environmental sensors—empowering communities to collect and monitor conditions in their air, water, and other environmental media.

As outlined in EJ 2020: “New technologies and sensors have the potential to supplement regulatory monitoring, provide information on operating processes to facility managers and inspectors, and enable community engagement in the measurement of local pollution through the use of affordable, easy-to-use analytical tools (citizen science).” This emphasizes that citizen science advances environmental protection by helping local communities understand local problems and collect quality data that can be used to advocate for or solve environmental and health issues.

We are committed to providing the science and engineering solutions needed to realize that potential. It’s part of our strategy to ensure that the benefits of environmental protection reach every community across the country. That’s the promise of EPA research, and what every American deserves.

About the Authors: Fred Hauchman, Ph.D., is the Director of the Office of Science Policy, which is the lead organization for integrating, coordinating, and communicating scientific and technical information and advice across EPA’s Office of Research and Development (ORD), and between ORD and the agency’s programs, regions, and external parties.

Andrew Geller, Ph.D., is the Acting National Program Director for the Agency’s Sustainable and Healthy Communities (SHC) research program. SHC researchers are working to provide the knowledge, data, and tools local communities and others need to advance a more sustainable, healthy, and vibrant future. A major priority is delivering the research needed to support environmental justice.