Subscriber content preview. or Sign In

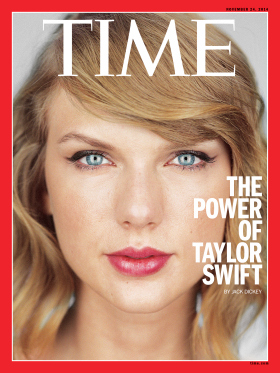

How pop's savviest romantic conquered the music business

Read TIME's full interview with Taylor Swift.

At eight o’clock on the most exciting night of her life, America’s most important musician was leading several dozen fans in a performance of “Happy Birthday” directed toward a young woman named Caylee, who had just turned 21. She presented Caylee with a bottle of champagne and a card. “Do you know what kind of drinker you are yet?” the 24-year-old superstar asked the 21-year-old, as she put her arm around her. “Are you a happy drunk?”

Earlier that day, in the same Manhattan event space, Taylor Swift had charmed music-biz executives while waiters circulated with frenched lamb and lobster canapés. Her fifth album had come out that morning. She greeted bosses from iHeartMedia—formerly Clear Channel, recently rechristened—and …