‘Convening and Brokering’ in practice: sorting out Tajikistan’s water problem

In the corridors of Oxfam and beyond, ‘convening and brokering’ has become a new development fuzzword. I talked about it in my recent review of the Africa Power and Politics Programme, and APPP promptly got back to me and suggested a discussion on how convening and brokering is the same/different to the APPP’s proposals that aid agencies should abandon misguided attempts to impose ‘best practice’ solutions and instead seek ‘best fit’ approaches that ‘go with the grain’ of existing institutions in Africa. That discussion took place yesterday, and it was excellent, but that’s the subject of tomorrow’s blog. First I wanted to summarize the case study I took to the meeting.

recent review of the Africa Power and Politics Programme, and APPP promptly got back to me and suggested a discussion on how convening and brokering is the same/different to the APPP’s proposals that aid agencies should abandon misguided attempts to impose ‘best practice’ solutions and instead seek ‘best fit’ approaches that ‘go with the grain’ of existing institutions in Africa. That discussion took place yesterday, and it was excellent, but that’s the subject of tomorrow’s blog. First I wanted to summarize the case study I took to the meeting.

The best example I’ve found in Oxfam’s work is actually from Tajikistan, rather than Africa, but it’s so interesting that I wrote it up anyway. Here’s a summary of a four page case study. Text in italics is from an interview with Ghazi Kelani, a charismatic ex-government water engineer who led Oxfam’s initial work on water and is undoubtedly an important factor in the programme’s success to date. Ghazi is currently Oxfam’s Tajikistan country director.

Water is a key resource in Tajikistan, providing energy, irrigation and drinking water, but its management is chaotic, characterized at both national and local level by paralysis, multiple institutions with overlapping mandates and a state of disintegration in much of the supply network. In many communities, people have reverted to taking water directly from irrigation canals and rivers, and diarrhoea is the most common disease in the country.

Oxfam began working in Tajikistan in 2001, in response to 2 years of drought. Water and sanitation (WatSan) formed an important part of its programme. Concerns over sustainability prompted a review of the work after five years, producing dismaying findings. Oxfam decided to publish these and organized a conference at which it became clear that INGOs, state and private sector providers were all struggling to manage the institutional chaos.

People were knocking on Oxfam’s door saying ‘your water system is broken, please come and fix it.’ That prompted us to ask why they were still saying ‘your’. It raised issues of sustainability. Publishing the findings of the evaluation was the big moment – our own doubts resonated with others.

The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), the leader in the WatSan sector in Tajikistan, got involved, calling in its experts to check Oxfam’s research and develop a plan for how to address the issues raised. SDC asked Oxfam whether we would be interested in running a 3-5 year project, but Oxfam persuaded them to extend this to 10 years, due to the scale and nature of the challenges.

The resulting project (TajWSS) developed a theory of change that would now be described as ‘convening and brokering’.

The network meets every two months. We always have guests, and hot topics, keep it dynamic – a full afternoon, 1.30-4.30pm, and then an extended coffee break so people can network. We get a minimum of 55 people from different sectors – 17 government ministries and agencies; the UN family; INGOs; academia; the media; Tajiki civil society organizations; the private sector; parliament. Now the ‘big questions are flowing’. Lots of other stuff emerges from the side conversations, the coffee breaks. For example, private sector companies working with network members to develop local chlorination, or getting local banks to help communities with finance for investment. Maybe we should add vodka to the menu to keep people there a bit longer!

The network meets every two months. We always have guests, and hot topics, keep it dynamic – a full afternoon, 1.30-4.30pm, and then an extended coffee break so people can network. We get a minimum of 55 people from different sectors – 17 government ministries and agencies; the UN family; INGOs; academia; the media; Tajiki civil society organizations; the private sector; parliament. Now the ‘big questions are flowing’. Lots of other stuff emerges from the side conversations, the coffee breaks. For example, private sector companies working with network members to develop local chlorination, or getting local banks to help communities with finance for investment. Maybe we should add vodka to the menu to keep people there a bit longer!

Central to the new programme is that its work is not framed as a project, but rather about building sustainable institutions. Improving the communications between government actors and other stakeholders in the water and sanitation sector all contributed to building a better environment on decision making.

This approach is not as easy as it sounds, and requires a particular skill set from the facilitator:

Everyone agreed with the overall idea. Of course, when you raise issues that affect the pocket, for example proposing tax exemption for investment in infrastructure projects, the Ministry of Finance gets irritated and opposes. There are always winners and losers and the losers try to push back by any means they can. Some Ministers get pissed off and try to make trouble. We deal with it case by case – we have to be patient, diplomatic, absorb their anger. We try to keep everyone calm! We use participatory techniques, task groups to help on this. Sometimes the best solution is to ignore someone; sometimes to go to them twice a day and explain we are doing this for Tajikistan. By creating forums to tackle contentious issues, TajWSS has become the only well-functioning game in town.

Project Impact

The initial impact was institutional, with more practical impacts following later. TajWSS helped set up an Interministerial Co-ordination Council (IMCC), established by presidential decree, with membership from 14 ministries and government agencies. This meets four times a year to discuss policy and make decisions. TajWSS facilitates the meetings and helps the Chair (who is the Minister of Water). (Without our facilitation it wouldn’t happen).

Our biggest victory so far is the Water Law. We didn’t draft it – it has been there for years in somebody’s drawer. The network raised the importance of having a law, and someone dug it up, and we decided it was good enough for a start.

Why does a water law matter? Previously there were laws on water and agriculture, water and energy, but not on drinking water. This creates chaos, everyone claiming water supply rights, providing without any quality control. The law frames the issues, establishes who’s in charge, who regulates, who is the service provider and targets monopolies. It is bringing order to an important subsector.

claiming water supply rights, providing without any quality control. The law frames the issues, establishes who’s in charge, who regulates, who is the service provider and targets monopolies. It is bringing order to an important subsector.

Our other major breakthrough is on construction permits for rural infrastructure. Currently it is really unclear, even for the biggest company. Getting a permit takes a minimum of 2 years and needs 3 separate permits for land acquisition, the license to exploit natural resource and the license to build infrastructure. And people in rural areas have to go to the capital to get the permit, because local government is not empowered to make decisions. So we found some nice work from USAID and the World Bank on ‘single window reform’, proposing a 200 day maximum for approval, and we used that as the basis for our proposal. We mapped 72 procedures and started to cost each one and weed out the unnecessary ones. It’s now down to 19 steps, and 180 days, and we’re still trying to simplify further, e.g. a fast-track procedure for small scale infrastructure. The inter-ministerial council has already approved it and the president has signed off (presidential decree no. 282.)

These institutional breakthroughs are now starting to deliver concrete results, according to Ghazi

We have now got the government to co-fund the water infrastructure programme. The Minister of Finance wrote to the president saying ‘we will support the Oxfam initiative and contribute 30% of capital costs’. The other 70% is SDC money channelled via Oxfam. The first 3 constructions were finished in December 2012 and handed over to communities for service provision (operating and maintaining) and making an income. Three more are in the pipeline. The water has started flowing – initially to 9,000 people in 7 villages. By August 2013 at least 30,000 people will get access to sustainable water provision.

Lessons

- It’s comparatively rare for NGOs or aid agencies to adopt the approach of ‘we all see there’s a problem, but we’re not sure how to fix it, let’s work something out together’. In this case, though, that seems to work better than either service delivery, or advocacy based on a shopping list of ‘policy demands’.

- In this area, for credibility, being operational as Oxfam is really important

- Acknowledging failure, and going public with it, created the basis for a coalition to find new solutions

- Oxfam’s role in convening/brokering has managed to bring players together and build trust, leading to an emerging set of initiatives, both in public policy, and partnerships. Part of that is Oxfam’s international brand: ‘The reason we can convene is our credibility and knowledge but also our international brand. Before meetings people go and google Oxfam and when they see what we are doing, it gives them confidence. It also matters that as Oxfam we are not vulnerable to political pressure, whereas a local NGO might be.’

- Building on existing legislation (e.g. the shelved Water Law) can often be a faster route than starting from scratch.

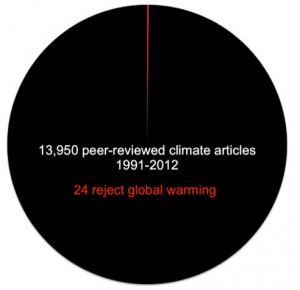

- Good research and killer facts (eg on permit procedures) can create conditions for policy change.

- Synergise and build on others projects rather than re duplicating or re-inventing the wheel

- I learned that facilitation and support of a network means taking care of each member organisation separately and in some cases individuals inside the member organisation.

I’m keen to collect more examples of this ‘problem without solution’/convening and brokering approach from NGOs and others – if you’ve got any, please let me know. Part two of this post tomorrow will report back on the ensuing discussion.