In the mind of Janet Yellen

In a speech by Janet Yellen on April 11, 2012, she talked about her preferred version of the Taylor rule to determine the Federal Funds rate.

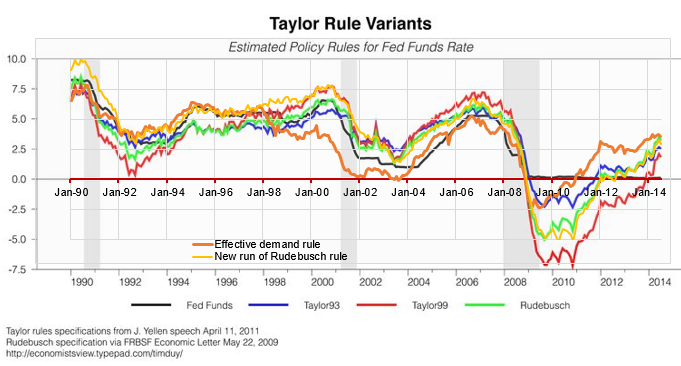

The Taylor (1993) rule calls for the federal funds rate to begin rising in early 2013, whereas the Taylor (1999) rule has its liftoff in early 2015, a lot closer to the optimal control path. A sizable literature has examined the performance of simple rules like these by conducting stochastic simulations with a range of economic models. Many studies, including Taylor’s own analysis, suggest that the Taylor (1999) rule generates considerably less variability in real activity and only slightly more variability in inflation than his original rule. Given the differential responses to economic slack across these two rules, this finding is hardly surprising, but it is a key reason why I consider the Taylor (1999) rule to be a more suitable guide for Fed policy.

The Taylor rule (1999) actually had “liftoff” in early 2014 according to Tim Duy, when the rule (1999) went positive. Then she puts the rule into perspective of her broader view on the future of monetary policy.

“While the Taylor (1999) rule can serve as a useful policy benchmark, its prescriptions fail to take into account some considerations that I consider important in the current context. In particular, this rule does not fully take into account the implications of the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates and hence tends to understate the rationale for maintaining a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy under present circumstances.”

Where is she going with this idea of “maintaining a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy”?

Importantly, resource utilization rates have been so low since late 2008 that a variety of simple rules have been calling for a federal funds rate substantially below zero, which of course is not possible. Consequently, the actual setting of the target funds rate has been persistently tighter than such rules would have recommended. The FOMC’s unconventional policy actions–including our large-scale asset purchase programs–have surely helped fill this “policy gap” but, in my judgment, have not entirely compensated for the zero-bound constraint on conventional policy. In effect, there has been a significant shortfall in the overall amount of monetary policy stimulus since early 2009 relative to the prescriptions of the simple rules that I’ve described.

She mentions a “significant shortfall”. What is this shortfall? In the end, it is not what she thinks.

“Analysis by some of my Federal Reserve colleagues suggests that monetary policy can produce better economic outcomes if it commits to making up for at least some portion of the cumulative shortfall created by the zero lower bound–namely, by maintaining a highly accommodative monetary policy for longer than a simple rule would otherwise prescribe. This consideration is one important reason that the optimal control simulation generates a more accommodative path than the Taylor (1999) rule.

So in effect, she will keep the effective Fed rate at the ZLB beyond the moment when the Taylor rule (1999) goes positive. In her mind, this will compensate for the period when the effective Fed rate could not go negative. Thus presently, she is keeping the Fed rate at the ZLB in order to make up for the shortfalls in policy when the rate could not go negative.

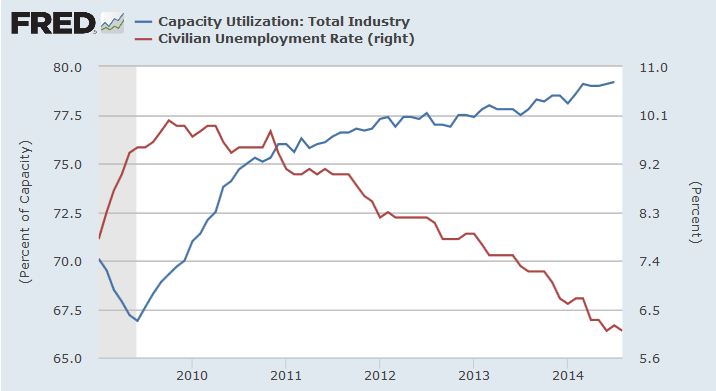

There is a risk though. She is expecting a couple of years of slack in the economy now to give her room for this maneuver and for normalizing the effective Fed rate. That vision of plentiful slack is what is in the mind of Janet Yellen. I for one do not believe that such plentiful slack is available due to the effective demand limit.

Analogies

The Fed rate should move with the preferred policy rate rule when the rule catches up to the Fed rate.

Let’s say you are walking to the store with a friend, and suddenly the friend drops back to tie their shoe. So you wait for your friend to catch up. When your friend catches up to you, do you allow them to walk a little further ahead to make up for the time they were behind? No… you start walking together. You are supposed to walk together.

Is there an analogy that makes sense of Janet Yellen’s plan? Could it be “affirmative action”?

In affirmative action, you have people who have been disadvantaged for a period of time, so they fall behind everyone else. So you create a policy to give them extra advantages to catch up.

But the analogy of affirmative action assumes a comparison of someone who did fall behind and someone who did not. So who fell behind who? In reality, labor fell behind capital. So does Janet Yellen’s maneuver to hold the Fed rate at the ZLB give labor an extra advantage? No… Her maneuver keeps giving capital extra advantages. It is a backwards policy. She is helping the advantaged thinking that they will help the disadvantaged once the labor market tightens up. However, reports are showing that on balance firms do not plan on raising labor’s share.

The Shortfall is actually Labor’s, not Capital’s

Unless Janet Yellen’s plan can directly help labor gain a higher share of national income, she is simply creating more policy for cheaper capital, cheaper labor and sustained inequality. She is harming society by giving extra advantages to capitalists, who have garnered pretty much all the gains from the recovery…

In her mind, she is on the correct curve for monetary policy. Yet in reality she is putting monetary policy and society behind the curve.