Department History

A Short History of the Department of State

The Expansionist Years, 1823-1867

The Expansionist Years, 1823-1867

Early Map of U.S.

From the birth of the Monroe

Doctrine in 1823 to the purchase of Alaska in 1867,

Americans devoted their national energies to extending their borders from

Atlantic to Pacific and to building a diversified economy. American

diplomats played an integral part in that process despite a lack of funding,

an absence of respect, and numerous hardships abroad.

Early Map of U.S.

From the birth of the Monroe

Doctrine in 1823 to the purchase of Alaska in 1867,

Americans devoted their national energies to extending their borders from

Atlantic to Pacific and to building a diversified economy. American

diplomats played an integral part in that process despite a lack of funding,

an absence of respect, and numerous hardships abroad.

The World in the Early-19th Century

A rare set of international circumstances gave the United

States the luxury to concentrate on domestic expansion during

the middle of the 19th century, because the country faced no serious

external threats until the Civil War

(1861-1865).

Napoleon surrenders his sword.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1812, a

stable and complex balance of power evolved in Europe. Maintaining that

delicate balance deterred possible aggressors from intervention in the New

World, because any nation tempted to interfere in the affairs of the Western

Hemisphere would have would have found itself in considerable difficulty

from its neighbors at home. The result was that the United States enjoyed an

extended period of tranquility—a very different atmosphere from the days of

the early republic.

Napoleon surrenders his sword.

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1812, a

stable and complex balance of power evolved in Europe. Maintaining that

delicate balance deterred possible aggressors from intervention in the New

World, because any nation tempted to interfere in the affairs of the Western

Hemisphere would have would have found itself in considerable difficulty

from its neighbors at home. The result was that the United States enjoyed an

extended period of tranquility—a very different atmosphere from the days of

the early republic.

The United States was free to practice a liberal form of nationalism, one that stressed a vague good will toward other nations rather than the pursuit of an active foreign policy. “Wherever the standard of freedom has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions, and her prayers be. But she does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” wrote John Quincy Adams in 1821. The republic would influence the world by offering an example rather than by exercising force. That sentiment would govern American foreign policy for nearly 100 years, until the outbreak of World War I.

President Millard Fillmore

For example, in response to the liberal revolutions of 1848 in Europe, President Millard Fillmore insisted that the United States must grant to others what it wanted for itself: the right to establish “that form of government which it may deem most conducive to the happiness and prosperity of its own citizens.” It became an imperative for the United States not to interfere in the government or internal policy of other nations. Although Americans might “sympathize with the unfortunate or the oppressed everywhere in their fight for freedom, our principles forbid us from taking any part in such foreign contests,” Fillmore explained.

A Foreign Policy of Inaction

The shift toward domestic concerns and the practice of liberal nationalism slowed the growth of the Department of State throughout the 19th century. Secretaries of State after 1823 fought to preserve, not expand, the influence of the Department. In foreign affairs, Presidents sought the counsel of the Secretary of the Treasury or the Secretary of War rather than that of the Secretary of State.

Secretary of State Edward Livingston

The low priority attached to foreign relations resulted in the open denigration of diplomacy and its practitioners. Secretary of State Edward Livingston himself summarized this widespread attitude, when he wrote that Americans thought of their ministers as privileged characters “selected to enjoy the pleasures of foreign travel at the expense of the people; their places as sinecures; and their residence abroad as a continued scene of luxurious enjoyment.” Congress often reflected a similar view of diplomats as lazy and under-employed. For example, in 1844 the House Committee on Foreign Affairs proposed to make diplomats work harder by assigning ministers to serve more than one country, so that only one minister would be needed to serve Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. In 1859 Representative Benjamin W. Stanton of Ohio said that he knew of “no area of the public service that is more emphatically useless than the diplomatic service—none in the world.”

The practice of the “spoils system,” the award of government appointments in return for political support, reinforced the idea that the Department of State and the Diplomatic and Consular Services were filled with unqualified loafers. President Andrew Jackson believed that “the duties of public officers are . . . so plain and simple that men of intelligence may readily qualify themselves for their performance . . . More is lost by the long continuance of men in office than is generally to be gained by their experience.” Attitudes like this perpetuated both amateurism in government and a disdain for public service. The egalitarian celebration of the common man worked against efforts to improve the quality and status of those who conducted foreign relations.

Some ministers still gained appointment because of their experience and talent. For example, two distinguished historians headed diplomatic missions: George Bancroft (United Kingdom, 1846-49) and John Lothrop Motley (Austria, 1861-67). More often, however, personal wealth, political services, or social position, were the only requirements. Many lacked qualifications—even the most elementary knowledge of diplomatic etiquette. A tale is often told, most likely apocryphal, that in 1830 John Randolph of Virginia actually addressed the Russian Tsar, “Howya, Emperor? And how’s the madam?”

Distinguished historian and statesmen, George Bancroft

One of the few talented diplomats of the era who made a career in the Diplomatic Service, Henry Wheaton, argued in vain for a professional service that recognized merit and granted tenure to the deserving. Those with necessary qualifications, linguistic skill, awareness of diplomatic forms, and with appropriate experience, should, he thought, “be employed where they can do most service, while incapable men should be turned out without fear or partiality. Those who have served the country faithfully and well ought to be encouraged and transferred from one court to another, which is the only advancement that our system permits of.”

The strains of office, including domestic political criticism, imposed great burdens on most Secretaries of State. One of them, John Clayton of Delaware who served President Zachary Taylor in 1849-1850, noted the consequences: “The situation I have filled,” he wrote, “was . . . more difficult, more thorny and more liable to misrepresentation and calumny than any other in the world, as I verily believe.”

The Department Reorganized—Again

The difficulties of those who conducted the nation’s foreign relations led two of President Jackson's Secretaries of State, Louis McLane and John Forsyth, to undertake another full-scale reorganization of the Department from 1833 to 1836. They instituted a bureau system, under the direct supervision of the Chief Clerk, to permit the orderly conduct of business. The Diplomatic Bureau and the Consular Bureau were the most important of the six new bureaus.

Secretary of State Louis McLane

Both bureaus were structured in the same way. In each, three clerks managed overseas correspondence. One clerk was responsible for England, France, Russia, and the Netherlands. Another dealt with the rest of Europe, the Mediterranean, Asia, and Africa. A third communicated with the Americas. A third bureau, for translating and miscellaneous other duties, supported their work. Three other bureaus handled: a) domestic and administrative matters, including archives, laws, and commissions; b) domestic correspondence, Presidential pardons, remissions, and copyrights; and c) disbursing and superintending.

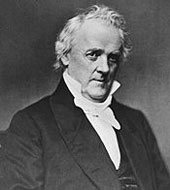

As early as 1846, Secretary of State James Buchanan saw a flaw in the new system and asked Congress to create the position of Assistant Secretary of State, to be filled by an eminent individual with diplomatic expertise. Unfortunately, Congress chose not to authorize the new position until 1853. A second Assistant Secretary position was permitted in 1866. William Hunter, who began his service in the Department in 1829, served as Chief Clerk from 1852 to 1866, when he became the second assistant secretary of state. Hunter held the position until his death in 1886.

Secretary of State James Buchanan

The number of overseas missions increased from 15 in 1830 to 33 in 1860. Most posts were located in Europe or Latin America, with only modest representation in East Asia and the Pacific. Ministers were sent to China in 1843 and Japan in 1859, and a resident commission was established in the Hawaiian Islands in 1843.

By 1860, 45 people held appointments in the Diplomatic Service, a remarkably small staff for 33 separate missions. Some ministers were forced to supplement their staffs by appointing “unpaid attachés,” usually young men of private means who performed some duties in return for an introduction into local society and opportunities for personal study and travel. Total overseas diplomatic expenditures rose from $294,000 in 1830 to $1.1 million in 1860.

Consular Services Expands; Many Hardships

Similar growth occurred in the Consular Service. The number of consulates exactly doubled from 141 in 1830 to 282 in 1860, and the number of consular agencies increased even more dramatically from 14 to 198 in the same period. Consular Service increases reflected the growing importance and volume of foreign trade.

While most diplomats were stationed in urban areas, consuls followed trade to some of the roughest and most remote spots on earth. Their lives—however short—were characterized by numerous hardships. The American consul at Genoa during the 1840s, C. Edwards Lester, summarized the situation: “An American consul is often a foreigner, almost always a merchant, can’t live on his fees, nor even pay the necessary expenses of his office; [he] is scolded or cursed by everybody that has anything to do with him, and is expected to entertain his countrymen, not only with hospitality but with a considerable degree of luxury.”

Despite its difficulties, Genoa was clearly a more desirable post than the Brazilian port of Pernambuco (now called Recife). In 1858, Consul Walter Stapp reported from Pernambuco that one of his predecessors had resigned before taking up his office because he had received “such mournful accounts of this place as to disgust him in advance of his arrival.” Moreover, he continued, “four others have left their bones to bake in these fearfully hot sands, without a slab of stone or a stick of wood to point the stranger to their graves.”

Beset by difficult climates and low salaries, consuls rarely received much assistance from the Government of the United States. In 1833, Secretary of State Edward Livingston noted that officials in the domestic service of the nation were “surrounded with the means of obtaining information and advice” but that “abroad, an officer is entrusted with the most important function, out of the reach of control or advice, and is left with, comparatively speaking, no written rules for his guidance.”

Congress Takes a Hand in Reform

Congress took no action to improve the lives of American representatives abroad until 1856, when it enacted legislation to reform the Diplomatic and Consular Services. The law concentrated on the most publicized problem—inadequate compensation. It prescribed salaries for ministers that ranged from $10,000 per year for most locations to $17,500 per year for London and Paris. While this was an adequate salary for the mid-19th century, that $17,500 salary cap for heads of mission remained in effect for the next 90 years. Consuls, too, were given regular salaries and the fees that they collected were sent to the Treasury. Written regulations were developed to improve the performance of the foreign services.

The Act of 1856 was a step forward, but it fell short of providing for truly professional foreign services. For some in the Consular Service, the transition was painful since consuls now had to rely solely on their salaries, which were often insufficient for a comfortable lifestyle. The novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, who experienced both the fee-based and salary systems as U.S. consul in Liverpool, disliked the new salary arrangement. Upon leaving Liverpool in 1857, he commented that his successor, to be successful, would have to be either “a rich man or a rogue.” His remark was prescient. An auditor reported in 1861 that one of Hawthorne’s successors as consul in Liverpool had not reported expenditures of public money for three years, “contracting public and private debts, which . . . probably exceed $200,000. It is perhaps some consolation to know that this plunderer no longer graces the Government abroad.”

Diplomatic Achievements

Despite the ramshackle nature of the foreign affairs establishment, the

Department of State was still able to make significant contributions to the

nation during this period.

Image of a page from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)

Perhaps the most striking achievement was the successful

resolution of many outstanding difficulties with Great Britain, the one

nation able to threaten the security of the United States. After the

unfortunate War of 1812,

Anglo-American controversies were all peacefully resolved: the Webster-Ashburton treaty of

1842 settled the boundary between northeastern Maine and Canada,

the Oregon treaty of

1846 extended the U.S.-Canadian border to the West coast, and the

Clayton-Bulwer treaty of 1850 provided an understanding on the construction

of any future canal across Central America.

Image of a page from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)

Perhaps the most striking achievement was the successful

resolution of many outstanding difficulties with Great Britain, the one

nation able to threaten the security of the United States. After the

unfortunate War of 1812,

Anglo-American controversies were all peacefully resolved: the Webster-Ashburton treaty of

1842 settled the boundary between northeastern Maine and Canada,

the Oregon treaty of

1846 extended the U.S.-Canadian border to the West coast, and the

Clayton-Bulwer treaty of 1850 provided an understanding on the construction

of any future canal across Central America.

Of equal importance were successful negotiations that furthered American domination of the continent. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) was of key importance because it ended the Mexican War and annexed a tremendous amount of territory north and west of the Rio Grande to California. The purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 was also a significant triumph for diplomacy. Despite the generally amateurish nature of diplomacy at this time, no serious setbacks marred the nation's foreign affairs between 1823 and 1867.

Secretary of State William Seward

One outstanding diplomat did serve the United States under Abraham Lincoln during the most serious 19th century challenge to the nation’s security—Secretary of State William Henry Seward.

Secretary of State William Seward

The American Civil War created excellent opportunities for European nations to meddle in the Western Hemisphere, either by violating the Monroe Doctrine or by extending aid to the rebellious South. In the initial stages of the war, Secretary of State Seward, ambitious and powerful, tried to gain control of President Lincoln’s Cabinet and implement policies on his own authority. Fearing that Lincoln was inadequate to the task, Seward complained that the administration had no policy in dealing with the seceding Southern states and he offered to take over the policy functions of the Government.

Lincoln outmaneuvered Seward, but in the process gained his respect. In time, the two developed a remarkably effective collaboration. Working through Charles Francis Adams, the U.S. Minister in London, Seward was able to prevent British recognition of the Confederate States and preserve British neutrality, a move that severely handicapped the southern quest for independence. The Secretary's success in fending off serious trouble during the Civil War demonstrated that great achievements in foreign relations almost always depended on close relations between the President and the Department of State.

Perhaps in part because of his successful leadership of the Department and his strong pro-Union stance, Seward was also a target of the plot that led to Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. Recuperating at home from a recent carriage accident, Seward was helpless when a conspirator entered his home just as Lincoln was being murdered. Seward managed to fend off the full force of his attacker until his son Frederick, who was Assistant Secretary of State at the time, rushed into the room to try to protect his father. Secretary Seward was stabbed in the face and throat, and his son was wounded more seriously. Both recovered, however, and continued to serve another four years under Lincoln’s successor, President Andrew Johnson. Seward is the only U.S. Secretary of State in history to be the target of a would-be assassin.

Seward had two major postwar diplomatic achievements: the removal of French troops from Mexico and the purchase of Alaska from Russia. During the Civil War, French troops had moved into Mexico, ostensibly to collect debts from the bankrupt Mexican Government. Supported by these troops—and in violation of the Monroe Doctrine—Napoleon III of France installed the Archduke Maximilian of Austria as Emperor of Mexico in 1864. As long as the Civil War continued, Seward could only protest. After the war, Seward skillfully escalated his diplomatic protests, while resisting American domestic pressures for a military expedition into Mexico. In 1867, Napoleon finally acquiesced to Seward’s careful diplomacy and withdrew the French troops.

Seward’s interest in buying Alaska derived from his geopolitical vision. Like many 19th century American political figures, he envisioned an expanding American empire increasingly involved in foreign commerce, including the China trade. Although some of his expansionist initiatives were unsuccessful, Seward appropriated the Midway Islands and, most important, in early 1867 negotiated with the Russian minister in Washington for the purchase of Alaska for $7.2 million. Although the purchase was widely satirized as “Seward’s folly” or “Seward’s icebox,” the Secretary correctly gauged the widespread popular support for the treaty, which the Senate overwhelmingly approved.

Conclusion

The triumph of Union forces in 1865 finally ended the dispute over the relative merits of national authority and states’ rights. The nation emerged from the Civil War more powerful and secure than at any time in its history. Because of the balance of power in Europe, the United States would remain largely immune from international dangers for the next 50 years.