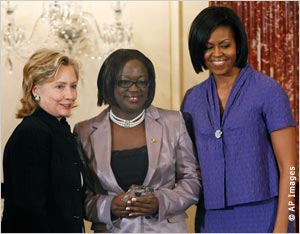

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and first lady Michelle Obama present the 2010 International Women of Courage Award to Ann Njogu of Kenya.

On the one hand, there is the argument that “putting a spotlight” on human rights abuses and the people who fight them actually helps.

In her remarks March 10 at the Women of Courage awards ceremony, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton praised women activists everywhere who have endured isolation, intimidation, violence and imprisonment and even faced death in their efforts to advance freedom and equal rights for everyone. Clinton said the stories of these women “deserve to be heard.” By publicly honoring them, the message is sent that although these activists “may work in lonely circumstances, they are not alone.”

Ann Njogu of Kenya, one of the Women of Courage awardees, gave a rather impassioned speech at an event sponsored by American Women for International Understanding (AWIU), a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization.

“Should this award mean nothing for those who oppress us, it means so much for the children, the elderly men, the women who find themselves in paralyzing poverty, poor leadership, bad governance, corruption that would otherwise have realized their fullest potential,” Njogu said. She said activists who win awards are a symbol for many others who labor in obscurity but who can feel “vindicated” by international recognition. She also added that such honors send “very strong signals to our respective governments that they must change and include human rights and virtues and standards in all they do and in the various institutions of governance.”

Inspiring words indeed. But on the other hand, a U.S. Foreign Service officer who has experience in the field told me that such awards often give activists a false sense of security. “They [the awardees] often end up in the same prisons as activists who don’t get awards,” the officer told me. And that, I can tell you, is one of the worst fears among the people who work at America.gov: That by telling the inspiring stories of brave human rights activists, we actually hurt them.

It’s a hard choice to make. What are your views?