Short Puffs Keep Dawn Chugging Along

Tuesday, December 4th, 2012

As NASA’s Dawn spacecraft makes its journey to its second target, the dwarf planet Ceres, Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer, shares a monthly update on the mission’s progress.

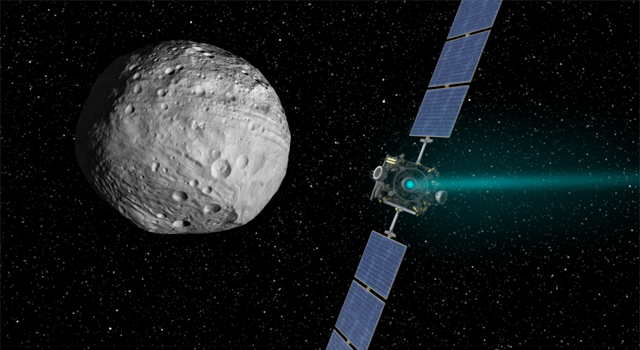

Artist’s concept of NASA’s Dawn spacecraft at its next target, the protoplanet Ceres. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Dear Dawndroids,

Dawn is continuing to gently and patiently change its orbit around the sun. In September, it left Vesta, a complex and fascinating world it had accompanied for 14 months, and now the bold explorer is traveling to the largest world in the main asteroid belt, dwarf planet Ceres.

Dawn has spent most of its time since leaving Earth powering its way through the solar system atop a column of blue-green xenon ions emitted by its advanced ion propulsion system. Mission controllers have made some changes to Dawn’s operating profile in order to conserve its supply of a conventional rocket propellant known as hydrazine. Firing it through the small jets of the reaction control system helps the ship rotate or maintain its orientation in the zero-gravity of spaceflight. The flight team had already taken some special steps to preserve this precious propellant, and now they have taken further measures. If you remain awake after the description of what the changes are, you can read about the motivation for such frugality.

Dawn’s typical week of interplanetary travel used to include ion thrusting for almost six and two-thirds days. Then it would stop and slowly pirouette to point its main antenna to Earth for about eight hours. That would allow it to send to the giant antennas of NASA’s Deep Space Network a full report on its health from the preceding week, including currents, voltages, temperatures, pressures, instructions it had executed, decisions it had made, and almost everything else save its wonderment at operating in the forbidding depths of space so fantastically far from its planet of origin. Engineers also used these communications sessions to radio updated commands to the craft before it turned once again to fire its ion thruster in the required direction.

Now operators have changed the pace of activities. Every turn consumes hydrazine, as the spacecraft expels a few puffs of propellant through some of its jets to start rotating and through opposing jets to stop. Instead of turning weekly, Dawn has been maintaining thrust for two weeks at a time, and beginning in January it will only turn to Earth once every four weeks. After more than five years of reliable performance, controllers have sufficient confidence in the ship to let it sail longer on its own. They have refined the number and frequency of measurements it records so that even with longer intervals of independence, the spacecraft can store the information engineers deem the most important to monitor.

Although contact is established through the main antenna less often, Dawn uses one of its three auxiliary antennas twice a week. Each of these smaller antennas produces a much broader signal so that even when one cannot be aimed directly at Earth, the Deep Space Network can detect its weak transmission. Only brief messages can be communicated this way, but they are sufficient to confirm that the distant ship remains healthy.

In addition to turning less often, Dawn now turns more slowly. Its standard used to be the same blinding pace at which the minute hand races around a clock (fasten your seat belt!). Engineers cut that in half two years ago but returned to the original value at the beginning of the Vesta approach phase. Now they have lowered it to one quarter of a minute hand’s rate. Dawn is patient, however. There’s no hurry, and the leisurely turns are much more hydrazine-efficient.

With these two changes, the robotic adventurer will arrive at Ceres in 2015 with about half of the 45.6-kilogram (101-pound) hydrazine supply it had when it rocketed away from Cape Canaveral on a lovely September dawn in 2007. Mission planners will be able to make excellent use of it as they guide the probe through its exploration of the giant of the main asteroid belt.

Any limited resource should be consumed responsibly, whether on a planet or on a spaceship. Hydrazine is not the only resource that Dawn’s controllers manage carefully, but let’s recall why this one has grown in importance recently.