posted by Dr. Amber Jenkins

17:00 PDT

From Sharon Ray, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Sixty-three percent of Americans believe that global warming is happening, but many do not understand why. That's according to the results of a new report out from the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. The study has identified a number of important gaps in public knowledge and common misconceptions about climate change (which Big Fat Planet will write about in more detail here later.

To help remedy some of the confusion, last weekend NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena hosted a public forum on climate change. Gray skies overhead caused some worries about attendance, but 160 people from the local community came to hear scientists talk about their latest research. The talks included discussion of:

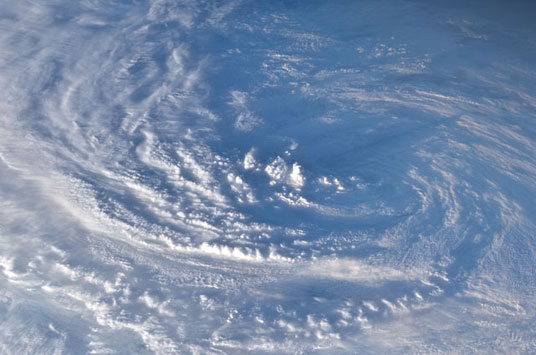

- The planet's carbon cycle, clouds and ozone

- How NASA’s upcoming Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) mission will help us determine Earth’s carbon dioxide sources (where it’s generated) and sinks (where it’s absorbed)

- How scientists use satellites to study Earth’s atmosphere

- How the greenhouse effect is a good thing (it’s made life on Earth possible by keeping the temperature warm enough to be habitable), but it’s the slight change in the balance of gases that is causing the Earth to warm

- What’s causing the loss of ice mass on our planet, the difference between sea ice and land ice and how each is affected by climate change

- Sea level rise, and the fact that the rate of the rise is increasing

- How to maintain balance in writing news stories on climate change science without giving undue weight to non-science-based opinion

- What we can do about climate change - it's about more than just recycling

- Promoting green practices locally

Audience questions varied from "Are climate models getting too complicated to understand?" to "How do volcanoes affect climate?" and "Why are the big countries not on board with climate regulation?" And the $64,000 question: "When it comes to discussions of climate change, why is population control not talked about as a possible solution?" On this unpalatable issue, scientist JoBea Holt relayed findings from population studies that suggest that if girls are educated, it tends to reduce the number of babies, and that once family incomes and health improve, families don’t need to have lots of children to insure that some grow to adulthood.

Lots of food for thought, but hopefully a useful event in terms of getting some of the scientific knowledge out there. JPL’s Green Club organized the whole shebang, and will repeat it next year. If you missed it, and want to catch up on what was said, visit our USTREAM archive. The speakers’ slides can be found here.

Sharon is an outreach coordinator for NASA’s Atmospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) instrument.