The United States will play host to UNESCO’s World Press Freedom Day event in 2011, from May 1 – May 3. The celebration will be held in Washington, DC, and will carry the theme “21st Century Media: New Frontiers, New Barriers.”

During the event, UNESCO will award the Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize, which honors a person, organization or institution that has notably contributed to the defense and/or promotion of press freedom, especially where risks have been undertaken. The recipient is determined by an independent jury of international journalists.

In a statement about World Press Freedom Day 2011, Philip J. Crowley, Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs at the U.S. Department of State said:

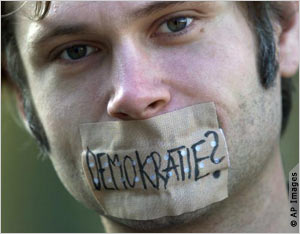

“New media has empowered citizens around the world to report on their circumstances, express opinions on world events, and exchange information in environments sometimes hostile to such exercises of individuals’ right to freedom of expression. At the same time, we are concerned about the determination of some governments to censor and silence individuals, and to restrict the free flow of information. We mark events such as World Press Freedom Day in the context of our enduring commitment to support and expand press freedom and the free flow of information in this digital age.”

For further information regarding World Press Freedom Day Events for program content, you can visit the World Press Freedom Facebook page http://www.connect.connect.facebook.com/WPFD2011

There’s good news and bad news about new media. First the good news: The Internet, mobile phones, and other types of “new media” are making information sharing infinitely easier. For the first time in

There’s good news and bad news about new media. First the good news: The Internet, mobile phones, and other types of “new media” are making information sharing infinitely easier. For the first time in  press freedom declined for the eighth consecutive year, and only one in six people live in countries with genuinely free media. And – as I learned from attending

press freedom declined for the eighth consecutive year, and only one in six people live in countries with genuinely free media. And – as I learned from attending  increasingly restrict access to these tools, crack down on journalists, and crush

increasingly restrict access to these tools, crack down on journalists, and crush

Need a challenge? Try covering intelligence issues as a journalist. Like other beats in journalism, you are heavily reliant upon getting people to talk to you, in addition to any other detective work you can manage on your own. But unlike other beats, you are focusing on topics in which many people are actively trying to deny you information, or even steer you in the wrong direction.

Need a challenge? Try covering intelligence issues as a journalist. Like other beats in journalism, you are heavily reliant upon getting people to talk to you, in addition to any other detective work you can manage on your own. But unlike other beats, you are focusing on topics in which many people are actively trying to deny you information, or even steer you in the wrong direction.