Influenza is unpleasant for many, and for some people, can be deadly. (Photo: NatalieJ via Flickr/Creative Commons)

Imagine that one day soon when you tune in to your favorite radio or TV station for the latest weather forecast, you’re given a flu forecast as well.

Adapting techniques used in modern weather prediction, scientists at Columbia University and the National Center for Atmospheric Research have come up with a way to produce localized forecasts of seasonal influenza outbreaks.

The researchers hope their new flu forecasting system, still in its initial phases, will serve both local and international health officials with highly detailed information, while also providing easier-to-understand versions for the general public. The researchers plan to get the system to an operational state within the next year or two.

Jeffrey Shaman, assistant professor of Environmental Health Sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health is the lead author of the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He says peak flu season can greatly vary from year to year, and from region to region. For example, Atlanta, a Southern U.S. city might reach its peak flu season weeks ahead of Anchorage in the far northwest.

Students in Kazakhstan wear surgical masks to help prevent the spread of flu during the 2009 swine flu outbreak. (Photo: Nikolay Olkhovoy via Wikmedia Commons)

The system will track flu outbreaks from week to week, location to location, showing the prevalence of flu in our own areas.

“I think what you can expect from it is weekly prognostications, weekly predictions, of how far in the future the peak of a flu outbreak is expected to be,” said Shaman.

Comparing his team’s flu forecasts to weathercasts we’re all used to, Shaman says the meteorological forecasts tell you, for example, that there’s an 80 percent chance of rain tomorrow, which prompts you to expect wet weather.

The flu forecast, on the other hand, would tell you that the peak of the flu season will be hitting your area within perhaps the next week or month reminding you to take any steps necessary to minimize the impact of the flu on you and your family.

The influenza forecast will also be able to provide data to health officials on the size and scope of the outbreak as well, allowing them to better plan a public health response.

Previous research conducted by Shaman and his colleagues found that U.S. wintertime flu epidemics were most likely to take place following a spell of very dry weather.

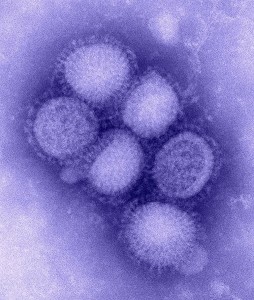

A microscopic image of the H1N1 (swine flu) influenza virus. In 2009, the World Health Organization declared this new strain to be a pandemic.

Using a computer model that incorporated this finding and feeding it web-based estimates of flu-related sickness in New York City from the winters of 2003-04 and 2008-09, Shaman and co-author Alicia Karspect of the the National Center for Atmospheric Research were able to produce weekly flu forecasts for those time periods that predicted the peak timing of the outbreak more than seven weeks ahead of the actual peak.

Shaman says that three ingredients are needed to do this kind of forecasting.

First, a mathematical model that describes the transmission of influenza within a specific population or community.

Next, real-time observations of what’s currently going on in the real world. Shaman says data comes from web-based estimates of influenza-like illnesses, recorded by various hospitals and clinics that see or treat patients with symptoms consistent with the flu.

And finally, a statistical or data assimilation method similar to those used in weather forecasting, to pull in data from the observations into the model that generates the predictions.

Yes, a flu shot may sting a little bit but the CDC recommends a yearly flu vaccine as the first and most important step in protecting ourselves against flu viruses. (Photo: US Navy)

Variations made to the incoming data stream, as conditions change, keep the model updated and on track to better reflect real-world conditions allowing for much more accurate forecasts.

Shaman and his research colleagues plan to test their system in other localities across the US by using up-to-date data.

“There is no guarantee that just because the method works in New York, it will work in Miami,” Shaman said.

Jeffrey Shaman joins us this weekend on the radio edition of “Science World.” Tune in to the radio program (see right column for scheduled times) or check out the interview below.

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Science World is VOA’s on-air and online magazine covering science, health, technology and the environment.

Science World is VOA’s on-air and online magazine covering science, health, technology and the environment.