Far From Home: Congolese Refugees in Southern Sudan

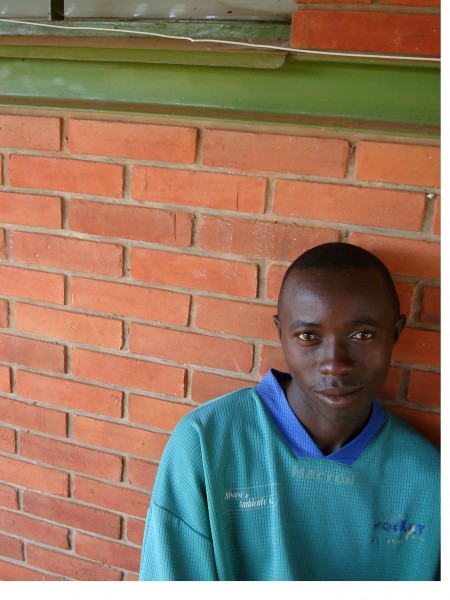

Makpandu Refugee Camp, Southern Sudan

Living at the geographic intersection of the region’s most complex and violent realities, thousands of Congolese refugees have recently fled into southern Sudan’s Western Equatoria State. They had escaped attacks staged by LRA rebels on their communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo early last year.

Operating in southern Sudan, eastern Congo, and northern Uganda, the LRA wages guerrilla warfare against the government in Uganda, but civilians have borne the brunt of their attacks. LRA rebels have murdered over twenty thousand people and abducted tens of thousands of children in the last twenty years. In mid-December 2008, the Ugandan army launched a US-backed attack against the LRA in an attempt to eliminate its entire senior leadership. The operation was a spectacular failure and resulted in the dispersal of the LRA across northeastern Congo. On the 24th of December, the LRA conducted simultaneous raids on villages across the Doruma region in northeastern Congo, targeting Christmas celebrations. At least 850 people died in these “Christmas massacres.” By mid-January 2009, 8,000 Congolese refugees had arrived in South Sudan.

Over 2,700 of these Congolese refugees are currently sheltering in Makpandu, a camp established by the U.N. to move them safely away from the border and the LRA’s occasional incursions into Sudan.

The Enough Project recently documented the stories of Francoise and Monique*, two refugees living in Makpandu:

People from around the area fled, as the LRA attacked multiple villages. As she ran toward Sudan, Francoise learned that her own village was targeted too. The militia had corralled her husband and some of the other older people into a house and burned it down.

When our conversation shifted to life before the LRA threat, Francoise brightened. She spoke lovingly of her husband, a high school teacher who taught geography and French. The pair had met when Francoise was 15 years old, and they married soon after. Francoise was also a teacher; she taught in a nursery school in their town…

“As soon as I harvest my groundnuts, I’m going to go home,” she said… We asked when the groundnuts would be ready for harvest. The end of December, Francoise said. She will only be here a couple more weeks.

As she spoke softly in her native Zande language, Monique, an 18-year-old Congolese refugee and orphan living in Makpandu refugee camp in southern Sudan, kept picking at her skirt as if trying to brush off some unseen dirt or thread… “When I was abducted, I wasn’t married,” she said without emotion. “But the tonton [LRA] made me take a soldier as my husband.” Five months later, Monique escaped during the commotion caused by a clash between the LRA and the southern Sudanese army.

Monique said she is hopeful that her mother and siblings are still at their home in the village of Kiriwo, but she hasn’t had any contact with them. At Makpandu, Monique is classified as an orphan because there was no one she knew who could take her in.

*Name has been changed.

Posted By: Ariana Berengaut WiW | January 19, 2010 | Comments (0)