Senate Procedure From a House Perspective

Senate Procedure From a House Perspective

Intended by the Founders to serve as a “check” on the popularly elected House of Representatives, process and procedure in the Senate has a far different emphasis from in the House. While the House’s institutional bias emphasizes efficiency, the Senate’s encourages deliberation and debate. It can be said that the fundamental rule in the House is “Whoever has 218 votes wins,” while the rule in the Senate differs: “There’s nothing you can do without 60 votes.” While the House is designed as a majoritarian institution, the Senate is structurally designed to protect the rights of the Minority by requiring super-majority votes for many procedural motions. This means that in any Senate where the majority party has less than a 10% margin, the ability of the Minority to demand concessions is greatly enhanced.

Intended by the Founders to serve as a “check” on the popularly elected House of Representatives, process and procedure in the Senate has a far different emphasis from in the House. While the House’s institutional bias emphasizes efficiency, the Senate’s encourages deliberation and debate. It can be said that the fundamental rule in the House is “Whoever has 218 votes wins,” while the rule in the Senate differs: “There’s nothing you can do without 60 votes.” While the House is designed as a majoritarian institution, the Senate is structurally designed to protect the rights of the Minority by requiring super-majority votes for many procedural motions. This means that in any Senate where the majority party has less than a 10% margin, the ability of the Minority to demand concessions is greatly enhanced.

COMMITTEES IN THE SENATE

Introduction of Bills and Referral. While the process of introducing bills in both chambers is similar, there are differences in the referral process. First and foremost, while the House requires that an introduced bill be referred to a committee by the Speaker on the same day it is introduced, the Senate requires that a bill be “read” twice before referral. While an introduced bill is usually considered as read twice and referred by unanimous consent, if a Senator objects to the second reading, the bill is not referred to committee and placed on the Senate’s Calendar of Business, known commonly as the “Legislative Calendar” and is eligible for floor action.

Committees and Reporting. Once a measure is referred to committee, the basic process is largely the same in both the House and Senate. The committee can hold hearings, mark up legislation, and report it to its repective chamber. In fact, with some minor exceptions, the basic rules for committees (clause 2 of rule XI of the Rules of the House and rule XXVI of the Standing Rules of the Senate) are largely the same.

Senate committees are by and large permitted to “originate” legislation (allowing committees to mark up and report unintroduced legislation), while in the House that power is largely restricted to the committees on Rules and Appropriations. Similarly, while a House committee reporting a measure must file a report with a significant amount of explanatory material, chairs of Senate committees can report a measure without a written report.

Committee Discharge Process. Procedures for bringing up legislation “stuck” in committee also differ. In the House, a committee’s referral is automatically discharged when considered by the House under suspension of the rules or pursuant to a rule reported by the Rules Committee. Members also have the ability to file a discharge petition, which gives that Member the ability to call up a measure still in committee if successful in obtaining 218 signatures on the petition.

In contrast, a Senator can simply just reintroduce a bill still in committee and object to the second reading, placing the bill on the Senate legislative calendar. A Senator could also seek to add the text of the bill to another measure through the amendment process, discussed later. While the Senate also has motions to discharge committees or suspend the rules, they are used so very infrequently.

SENATE FLOOR CONSIDERATION

Calling Up Legislation and the Motion to Proceed. In the House, the scheduling and consideration of legislation usually falls under the sole purview of the Speaker and the Majority leadership. In the Senate, the Majority Leader is the individual who reserves these rights. Unlike the House, however, while the Majority Leader can move to consider a particular bill, the outcome of that effort is not guaranteed. The Majority Leader can offer a motion to proceed to the consideration of a particular measure, which is fully debatable in the Senate. As a result, in order to begin consideration of a bill, the Majority Leader must close debate on the motion to proceed, generally through the use of a cloture motion.

Ending Debate: Cloture. While the House utilizes the previous question motion to cut off floor debate, the Senate invokes what is known as ‘cloture’ when the chamber’s members are unable to come to an unanimous consent agreement for the consideration of a bill or amendments.

When the Senate invokes cloture, several rules come into play for the further consideration of a bill or amendment:

1. 30-Hour Debate Cap. Once cloture is invoked, there is a 30-hour total time cap on debate.

That debate can include roll call votes, amendments, and other activities, so the ultimate

amount of debate time under the cap is often far less than 30 hours.

2. 1-Hour Per Senator Cap. The cloture rule limits each Senator to no more than 1-hour of

debate, on a “first-come, first-served” basis.

3. Amendment pre-filing. Only amendments that have been filed before the cloture vote may be

considered once cloture is invoked. First-degree amendments must be filed by 1:00 p.m.

on the day after the filing of the cloture petition; second-degree amendments may be filed

until at least one hour prior to the start of the cloture vote.

4. Germaneness. The Senate does not have a general rule of germaneness for amendments.

Once cloture is invoked, however, all amendments (and debate) are to be germane to the

clotured proposal. Similarly, the Chair is given additional powers under cloture. For example,

the chair has the authority to determine the presence of quorum, and can also rule

out-of-order dilatory motions or amendments, including quorum calls. The chair also has the

authority to determine the presence of a quorum.

Achieving Cloture. In order to begin the cloture process, at least 16 Senators must sign a cloture motion that states, “We, the undersigned Senators, in accordance with the provisions of Rule XXII of the Standing Rules of the Senate, hereby move to bring to a close the debate upon [the matter in question].” A cloture motion is of high enough privilege that a Senator may interrupt another Senator to present the cloture motion.

The Senate votes on the cloture motion one hour after it convenes on the second calendar day after the cloture motion was filed. This vote can only occur after a quorum call has established the presence of a quorum. The timimg of any cloture vote may be changed by unanimous consent, and the required quorum call often is waived the same way.

The cloture rule requires three-fifths of the Senators duly chosen and sworn to vote in favor of the motion, which equates to 60 votes when there are no vacancies in the Senate’s membership. Invoking cloture on a measure or motion to amend the Senate’s rules, however, requires the votes of two-thirds of the Senators present and voting, or 67 votes if all 100 Senators vote.

Holds. The filibustering of motions to proceed has led to the informal Senate practice known as a hold. Holds are essentially threats by a Senator to filibuster the motion to proceed. When a Senator indicates that they are placing a hold on a particular piece of legislation, they are not required to actually hold the floor by conducting a filibuster, but the leadership will not attempt to bring up the bill until the hold is cleared. Under the so-called “gentleman’s agreement” adopted at the beginning of the 112th Congress, Minority Leader McConnell agreed that the minority party would exercise “restraint” in filibusters of motions to proceed, which Majority Leader McConnell agreed to limit a practice to curtail amendments, known as “filling the tree”.

|

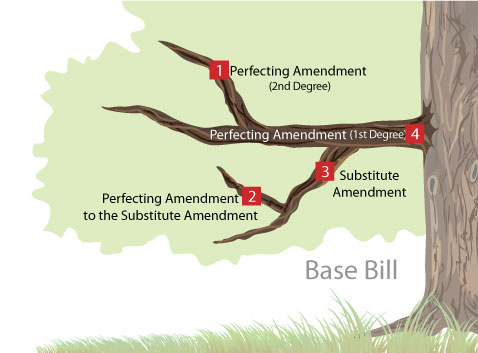

| Figure 1. The Amendment Tree. one tactic sometimes used in the Senate is known as "filling the tree," meaning that the Majority Leader sets up a cloture vote while all types of amendments are pending, limiting the ability of Senators to offer amendments. |

"Filling the Tree." This practice, when combined with a cloture motion, is a mechanism that allows the Majority Leader to create an amendment process akin to a closed rule in the House. Figure 1 shows the basic amendment tree that functions in both the House and the Senate. By offering an amendment of each type, the Majority Leader ensures that there is a pending amendment at each “branch” of the “tree”. Any Senator attempting to offer a further other amendment would be ruled out of order because it would be an amendment in the third-degree, something prohibited by both House and Senate rules.

OTHER NOTABLE PROCEDURAL DIFFERENCES IN THE SENATE

The myriad differences between House and Senate floor procedures also include:

The Senate does not have a “committee of the whole,” so a full quorum (51 Senators) is necessary for any action, as opposed to the comparatively smaller quorum of 100 House members, which constitutes the Committee of the Whole in the House. The rules of the Senate, however, require that the presiding officer assume the presence of a quorum, unless directly challenged by a Senator from the floor.

The nature of the Senate is such that they cannot schedule debate as tightly as in the House. When no other Senator is on the floor seeking recognition, a Senator will “suggest the absence of a quorum,” allowing the Senate to temporarily suspend formal proceedings while the Clerk calls the roll. The quorum call is then usually dispensed with by unanimous consent.

Unlike the Speaker, the Senate’s presiding officer (the Vice-President) may only speak on the Senate floor by unanimous consent and may only vote to break a tie.

FOUR IMPORTANT DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE HOUSE AND SENATE

1. No Previous Question Motion — The House has the ability to cut off debate by majority vote through the use of the previous question motion. The Senate does not have such a motion, and the only ways to restrict debate on a given question is through the cloture process or a unanimous consent agreement.

2. No Time Limits on Debate — Because the Senate is designed to be more deliberative than efficient, there are no time limits on debate on most questions, including procedural motions. A super majority is required to invoke cloture or all Senators must agree to a unanimous consent agreement, ultimately protecting the Senate minority.

3. No Consistent Germaneness Rule — The House has a germaneness rule which requires any amendment to be of the “same subject” as the matter being amended. During its regular practice, the Senate has no such standard, and even when germaneness is required under Senate rules — such as during the post-cloture debate time or during reconciliation — the Senate’s rule is far less stringent than the one employed by the House.

4. Senate Rules Committee is Administrative — Unlike the House Rules Committee, whose function is largely to structure floor debate, the Senate Rules Committee, while having jurisdiction over the Standing rules of the Senate, deals largely with administrative matters, such as office space, parking, and other matters which are addressed by the Committee on House Administration in the House.

FEATURES OF THE SENATE CHAMBER

Having only 100 members, the Senate chamber is smaller than the House chamber, but also has other differences:

Senators have individual desks. Senators’ desks and their positions are matters of seniority and tradition. A full discussion of the history of Senate desks, seating arrangements, and a current map showing Senators’ desks is available here.

The Senate does not employ electronic voting. When a Senator requests a recorded vote, the Clerk calls the roll of senators first alphabetically, and then reads the names of senators voting in the affirmative, and those voting in the negative. After that point a senator casts his or her vote in the well, and the Clerk repeats the vote.