-

Kant vs. Saint Augustine on Gun Control

Kant vs. Saint Augustine on Gun Control

- When Will We See a Harriet Tubman Biopic?

- How Online Dating Threatens Monogamy

-

Sponsor Content Supporting Human Connections

-

Politics

- Top Stories

- How Obama Could Beat the Second-Term Curse

- The Most Interesting Freshman: Ted Yoho

- The Right Debates Why Romney Lost

- Are People Being Unfair to the House Republicans?

- Picture of the Day: The Moment Obama Heard About the Newtown Shooting

- A Short Video Summary of the Government Spying Debate

-

Business

- Top Stories

- The Fiscal Cliff Deal FAQ

- Why Are College Textbooks So Absurdly Expensive?

- Sorry, Latvia Is No Austerity Success Story

- BuzzFeed, Andrew Sullivan, and the Future of Making Money in Journalism

- We Created 1.8 Million Jobs in 2012: Where Did They Come From?

- The 1 Thing the World's Smartest People Don't Get About the Fed

- Tech

- National

-

Global

- Top Stories

- Why Japan Can't Compete With China

- China's Growing Appetite for Illegal Drugs

- Russia's Ban Against U.S. Adoptions: The Human Cost

- Greetings of 'the Festive Season'

- Rooftop Gardens Pop Up in Beijing and Hong Kong

- 60,000 Dead in Syria? Why the Death Toll Is Likely Even Higher

- The Democracy Report

- Social and political change around the world

- What Happened to the Arab Spring?

-

Health

- Top Stories

- The Wisdom of the Ultrasound Party Trend

- The Self That Remains When Memory Is Lost

- Inside Chernobyl's Abandoned Hospital

- Creative Aging: The Emergence of Artistic Talents

- Study: Use Food to Make New Friends, Say Bonobos

- Study: Another Bad Thing About Fructose

- Study of the Day

- Study: Use Food to Make New Friends, Say Bonobos

- Dr. Hamblin's Emporium of Medicinal Wonderments

- Would Knee Replacements Make Me Taller?

-

Sexes

- Top Stories

- Men Brag About Their Salaries, but Women't Don't

- Why Many Victims of Sexual Harassment Stay Silent

- Gang Rape Isn't the Only Problem Indian Women Face

- The American Woman Who Wrote Equal Rights Into Japan's Constitution

- As a Girl in India, I Learned to Be Afraid of Men

- Online Dating Makes Me Long for Commitment, Not Avoid It

-

Entertainment

- Top Stories

- The Underrated Creativity of Sherlock Holmes

- The Shocking Rise (and More Shocking Fall) of the Redskins

- Epiphanies Don't Last: What Flannery O'Connor Got Right

- The Hollywood America Deserves

- What's So Hard to Understand About a Black Woman Who Loves Heavy Metal?

- The Myth of Harriet Tubman

- Pop Theory

- Smart, fun / fun, smart

- The Anthropological Reason It Feels Weird to Dance to Brubeck's 'Take Five'

- 1book140

- TheAtlantic.com's reading club

- 1book140 January Discussion Schedule: 'Just Kids'

- Track of the Day

- Track of the Day: 'Love Songs In the Night'

- Magazine

Alexis C. Madrigal

Alexis Madrigal is a senior editor at The Atlantic, where he oversees the Technology channel. He's the author of Powering the Dream: The History and Promise of Green Technology.

More

The New York Observer calls Madrigal "for all intents and purposes, the perfect modern reporter." He co-founded Longshot magazine, a high-speed media experiment that garnered attention from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the BBC. While at Wired.com, he built Wired Science into one of the most popular blogs in the world. The site was nominated for best magazine blog by the MPA and best science Web site in the 2009 Webby Awards. He also co-founded Haiti ReWired, a groundbreaking community dedicated to the discussion of technology, infrastructure, and the future of Haiti.

He's spoken at Stanford, CalTech, Berkeley, SXSW, E3, and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, and his writing was anthologized in Best Technology Writing 2010 (Yale University Press).

Madrigal is a visiting scholar at the University of California at Berkeley's Office for the History of Science and Technology. Born in Mexico City, he grew up in the exurbs north of Portland, Oregon, and now lives in Oakland.

What the First CES Looked Like

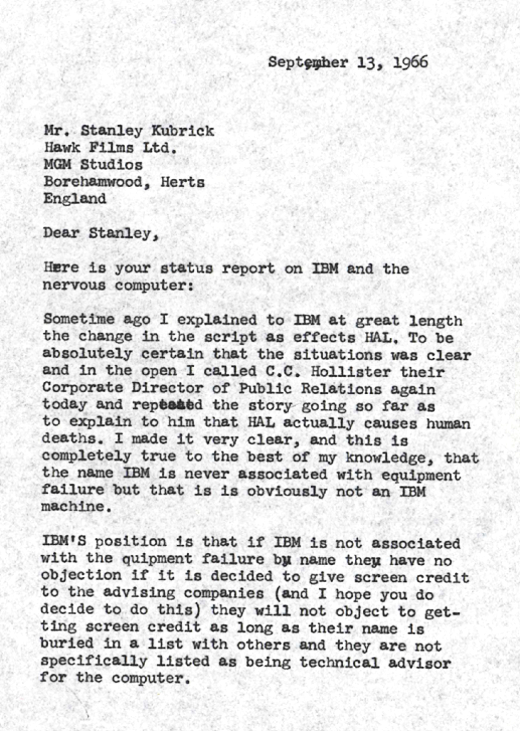

The Letter Stanley Kubrick Wrote About IBM and HAL

There's No Evidence Online Dating Is Threatening Commitment or Marriage

One guy's commitment issues don't mean the end of monogamy for the country. The first in a series of responses to Dan Slater's article "A Million First Dates."

Linda and Jeremy Tyson, a married couple who met on eHarmony, take a pedicab ride in New York City in 2010 (David Goldman/AP Images)

Linda and Jeremy Tyson, a married couple who met on eHarmony, take a pedicab ride in New York City in 2010 (David Goldman/AP Images)

The question at hand in Dan Slater's piece in the latest Atlantic print edition, "A Million First Dates: How Online Dating is Threatening Monogamy," is whether online dating can change some basic settings in American heterosexual relationships such that monogamy and commitment are less important.

Narratively, the story focuses on Jacob, an overgrown manchild jackass who can't figure out what it takes to have a real relationship. The problem, however, is not him, and his desire for a "low-maintenance" woman who is hot, young, interested in him, and doesn't mind that he is callow and doesn't care very much about her. No, the problem is online dating, which has shown Jacob that he can have a steady stream of mediocre dates, some of whom will have sex with him.

"I'm 95 percent certain," Jacob says of a long-term relationship ending, "that if I'd met Rachel offline, and I'd never done online dating, I would've married her.. Did online dating change my perception of permanence? No doubt."

This story forms the spineless spine of a larger argument about how online dating is changing the world, by which we mean yuppie romance. The argument is that online dating expands the romantic choices that people have available, somewhat like moving to a city. And more choices mean less satisfaction. For example, if you give people more chocolate bars to choose from, the story tells us, they think the one they choose tastes worse than a control group who had a smaller selection. Therefore, online dating makes people less likely to commit and less likely to be satisfied with the people to whom they do commit.

But what if online dating makes it too easy to meet someone new? What if it raises the bar for a good relationship too high? What if the prospect of finding an ever-more-compatible mate with the click of a mouse means a future of relationship instability, in which we keep chasing the elusive rabbit around the dating track?

Unfortunately, neither Jacob's story nor any of the evidence offered compellingly answers the questions raised. Now, let's stipulate that there is no dataset that perfectly settles the core question: Does online dating increase or decrease commitment or its related states, like marriage?

But I'll tell you one group that I would not trust to give me a straight answer: People who run online dating sites. While these sites may try to attract some users with the idea that they'll find everlasting love, how great is it for their marketing to suggest that they are so easy and fun that people can't even stay in committed relationships anymore? As Slater notes, "the profit models of many online-dating sites are at cross-purposes with clients who are trying to develop long-term commitments." Which is exactly why they are happy to be quoted talking about how well their sites work for getting laid and moving on.

It should also be noted: There isn't a single woman's perspective in this story. Or a gay person's. Or someone who was into polyamory before online dating. Or some kind of historical look at how commitment rates have changed in the past and what factors drove those increases or decreases. Instead we get eight men from the industry that, as we put it on our cover, "works too well."

But hey, maybe these guys are right. Maybe online dating and social networking is tearing apart the fabric of society. How well does the proposition actually hold up?

First off, the heaviest users of technology--educated, wealthier people--have been using online dating and networking sites to find each other for years. And yet, divorce rates among this exact group have been declining for 30 years. Take a look at these statistics. If technology were the problem, you'd expect that people who can afford to use the technology, and who have been using the technology, would be seeing the impacts of this new lack of commitment. But that's just not the case.

Does it follow that within this wealthy, educated group, online daters are less likely to commit or stay married? No, it does not.

Like I said, there's no data to prove that question one way or the other. But we have something close. A 2012 paper in the American Sociological Review asked, are people who have the Internet at home more or less likely to be in relationships? Here was the answer they found:

One result of the increasing importance of the Internet in meeting partners is that adults with Internet access at home are substantially more likely to have partners, even after controlling for other factors. Partnership rate has increased during the Internet era (consistent with Internet efficiency of search) for same sex couples, but the heterosexual partnership rate has been flat.

So, we have, at worst, that controlling for other factors, the Internet doesn't hurt and sometimes helps. That seems to strike right at the heart of Slater's proposition.

A 2008 paper looked at the Internet's ability to help people find partners and postulated who might benefit the most. "The Internet's potential to change matching is perhaps greatest for those facing thin markets or difficulty in meeting potential mates." This could increase marriage rates as people with smaller pools can more easily find each other. The paper also proposes that perhaps people would be *better* matched through online dating and therefore have higher-quality marriages. The available evidence, though, suggests that there was no difference between couples who met online and couples who met offline. (Surprise!)

So, here's the way it looks to me: Either online dating's (and the Internet's) effect on commitment is nonexistent, the effect has the opposite polarity (i.e. online dating creates more marriages), or whatever small effect either way is overwhelmed by other changes in the structure of commitment and marriage in America.

The possibility that the relationship "market" is changing in a bunch of ways, rather than just by the introduction of date-matching technology, is the most compelling to me. That same 2008 paper found that the biggest change in marriage could be increasingly "co-ed" workplaces. Many, many more people work in places where they might find relationship partners more easily. That's a big confounding variable in any analysis of online dating as the key causal factor in any change in marital or commitment rates.

But there's certainly more complexity than that lurking within what was left out of Jacob's story: how about changing gender norms a la Hanna Rosin's End of Men? How about changes that arose in the recent difficult economic circumstances? How about changes in where marriage-age people live (say, living in a walkable core versus the exurbs)? How about the spikiness of American religious observance, as declining church attendance rates combine with evangelical fervor? How about changing cultural norms about childrearing and marriage? How about the increasing acceptance of homosexuality across the country, particularly in younger demographics?

All of these things could bring about changes in the likelihood of people to meet and stay in relationships. And none of them have much to do with online dating. Yet our story places all of the emphasis for Jacob's drift on his desire to browse online dating profiles.

Is online dating a trend that's worth us looking into? Certainly. And there are even things that online dating sites may be able to do within their technical systems to negate the effects of thinking about possible partners as profiles rather than people. Slater cited Northwestern's Eli Finkel, who appears to have legitimate concerns about the structure of search and discovery on dating sites.

But the jumps and leaps from that observation--and Finkel's academic assessment in a recent paper--to blaming online dating for "threatening monogamy"? There's just so little support there.

And if you are going to make a hard deterministic argument, you better have some good evidence that it is the technology itself that is the actor, and not someone or something else. At any time in this big old world, there are lots of changes happening slowly. So many trend lines, so much data. In that world, there appears some undeniably shiny new thing: a technology! People--TED speakers, teenage skateboarders, venture capitalists, a grandfather, advertisers, deli counter clerks, accountants--standing amidst the swirl of the white swirl of the onrushing future look out and say, "This technology is changing everything!"

Flush with this knowledge of the one true cause of good/bad in the _____ Age, the magic technology key seems to unlock every room in the house, and all the doors on every neighbor's house, and the vault at Fort Knox, and the highest office at 30 Rock.

Of course, technology does have impacts. Certain types of technology, say, nuclear reactors, have politics in that they "are man-made systems that appear to require or to be strongly compatible with particular kinds of political relationships," as the political scientist Langdon Winner has shown. Some technological systems, the electric grid or cell phone networks, prove difficult to change, and make some kinds of behavior really easy, and others more difficult. A technology can tilt a set of interactions towards certain outcomes, which is precisely why some people want to ban specific types of guns.

So, you can say, in some sense, that a technology "wants" certain outcomes. Jacob from the story might say that online dating wants him to keep browsing and not commit. The electrical grid wants you to plug in. Or, the owners of Facebook want you to post more photographs, so they design tools--technical and statistical--to make you more likely to do so.

And it's not wrong to say that Facebook wants us to do things. But if you stop talking to your cousins because it's easier to update Facebook than give them a call, it's not right to say that Facebook made you do that. If you stop reading novels because you find Twitter more compelling, it's not correct to say that Twitter made you do that. Maybe you like real-time news more than the Bronte sisters, no matter what your better conception of yourself might say.

Maybe Jacob doesn't want to get married. Maybe he wants to get drunk, have sex, watch basketball, and never deal with the depths of a real relationship. OK, Jacob, good luck! But that doesn't make online dating an ineluctable force crushing the romantic landscape. It's just the means to Jacob's ends and his convenient scapegoat for behavior that might otherwise lead to self-loathing.

What Treadmills Were Made For

Providing horizontal motion for absurdly complex dance moves.

Megan Garber delivered a pocket history of the invention of the gym machine today. But she left out one key use for the treadmill: providing horizontal motion for absurdly complex dance moves. So, I'm filling in that gap by posting OK Go's 2009 video, via Steven Lehrburger.

Also: this is a lesson in technical affordance. If one can do something with a machine, people will figure out how to do it.

Lastly: I want to go to the gym where this is one of the fitness classes.

A Computational Model of the Human Heart

How we try to make sense of the wondrous organ, and when the mechanism fails.

The heart is a beautiful pump. While lacking the poetry of most odes to the heart, the Barcelona Supercomputing Center's project, Alya Red, pays homage to the organ by trying to model it. The task of simulating the way electrical impulses make the heart muscles contract to pump blood takes 10,000 processors.

These particular computing nodes are located in one of the world's 500 most powerful computers, which itself sits within a deconsecrated 19th-century chapel at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia.

This very 2013 arrangement came to my attention through a post by Emily Underwood at the science blog, Last Word on Nothing. An old friend of Underwood's pacemaker failed, causing him to have a stroke that robbed the man of his ability to speak.

Hundreds of thousands of computations simulate the organ's geometry, and the orientation of long muscle fibers that wring the heart when they contract. Now for the horrifying part: this requires the supercomputer to do so much math that it must break up the work among 10,000 separate processors. Even Fernando Cucchietti, a physicist who helped create the video, agrees that the heart's complexity has a dark side. At first, the video conveyed "too much wonder," he says "It was almost appalling."

Appalling wonder -- that just about says it. On good days, when I try to write about such things, I feel like an industrious housewife, tidying up cluttered corners and making clean, lemon-scented sentences. Maybe this new supercomputer model will make better pacemakers, or help devise new ways to mend my friend's broken heart. Then there are days like this, when I think about the tiny metal object that both enabled and derailed his life, and just feel speechless.

Some days, the mechanism fails.

Our Most Popular Technology Stories from 2012

The most-read posts of the outgoing year.

I think the best way to review what happened here on The Atlantic's technology pages is to take a look at the e-book we put out of our best work. But I respect the wisdom of the crowd, and I figure you might want to know what your fellow readers liked the most. So, here are our most popular stories of the year:

"This post, which will be updated over the next couple of days, is an effort to sort the real from the unreal. It's a photograph verification service, you might say, or a pictorial investigation bureau." -- Alexis C. Madrigal

2. Behold, the Toothbrush That Just Saved the International Space Station.

It was a little like Apollo 13 -- if its mission to the moon had been saved by a tool of good oral hygiene, that is. Yesterday the International Space Station, having battled electrical malfunctions for over a week, was repaired by a combination that MacGyver himself would have been proud of: an allen wrench, a wire brush, a bolt ... and a toothbrush. -- Megan Garber

3. When the Nerds Go Marching In.

"By the end, the campaign produced exactly what it should have: a hybrid of the desires of everyone on Obama's team. They raised hundreds of millions of dollars online, made unprecedented progress in voter targeting, and built everything atop the most stable technical infrastructure of any presidential campaign. To go a step further, I'd even say that this clash of cultures was a good thing: The nerds shook up an ossifying Democratic tech structure and the politicos taught the nerds a thing or two about stress, small-p politics, and the significance of elections." -- Alexis C. Madrigal

4. How Google Builds Its Maps--and What It Means for the Future of Everything.

"As we slip and slide into a world where our augmented reality is increasingly visible to us off and online, Google's geographic data may become its most valuable asset. Not solely because of this data alone, but because location data makes everything else Google does and knows more valuable." -- Alexis C. Madrigal

5. Why Sandy Has Meteorologists Scared, in 4 Images.

"For many, the hullabaloo raises memories of Irene, which despite causing $15.6 billion worth of damages in the United States, did not live up to its pre-arrival hype. By almost all measures, this storm looks like it could be worse: higher winds, a path through a more populated area, worse storm surge, and a greater chance it'll linger. The atmospherics, you might say, all point to this being the worst storm in recent history." -- Alexis C. Madrigal

6. We're Underestimating the Risk of Human Extinction.

"Unthinkable as it may be, humanity, every last person, could someday be wiped from the face of the Earth. We have learned to worry about asteroids and supervolcanoes, but the more-likely scenario, according to Nick Bostrom, a professor of philosophy at Oxford, is that we humans will destroy ourselves. Bostrom, who directs Oxford's Future of Humanity Institute, has argued over the course of several papers that human extinction risks are poorly understood and, worse still, severely underestimated by society." -- Ross Andersen

7. Google's Self-Driving Cars: 300,000 Miles Logged, Not a Single Accident Under Computer Control.

"Legally -- and ethically -- we will need to grapple with the questions about safety standards for autonomous machines. As Stanford Law School's Bryan Walker Smith said to me over email, "How well must these vehicles ultimately perform? Perfectly? Or something less -- an average human driver, a perfect human driver, or a computer with human oversight? And how should this be measured?" And, perhaps toughest of all, how will we make those decisions, and, really, who will make them?" -- Rebecca J. Rosen

8. How the Professor Who Fooled Wikipedia Got Caught by Reddit.

"Each tale was carefully fabricated by undergraduates at George Mason University who were enrolled in T. Mills Kelly's course, Lying About the Past. Their escapades not only went unpunished, they were actually encouraged by their professor. Four years ago, students created a Wikipedia page detailing the exploits of Edward Owens, successfully fooling Wikipedia's community of editors. This year, though, one group of students made the mistake of launching their hoax on Reddit. What they learned in the process provides a valuable lesson for anyone who turns to the Internet for information." -- Yoni Appelbaum

A Thought for You As You Stare Up at the Stars and Ponder the New Year

All the stars in the sky? That's nothing in the cosmic scheme of things.

flickr/dawn_perry

The Bad Astronomer, Phil Plait, points out that even when you look up into the infinitude of the night sky, even on December 31, even when you're out in the middle of nowhere contemplating the future, you're still only seeing a teensy, tiny fraction of all the stars just in our own galaxy.

When you look up at the night sky, it seems it's filled with stars. But you're only seeing a tiny, tiny fraction of all the stars in the Milky Way. Our galaxy is a disk 100,000 light years across, and with only a handful of exceptions, all the stars you see are less than 1000 light years away. Most are far closer than that! At best, you're seeing a few thousand stars out of the hundreds of billions in the Milky Way, a paltry fraction of 0.000003%!

Remember When Japanese Electronics Firms Were Dominant? Now They're Apple Suppliers

It was a very bad year for the country's gadget makers.

Glory days! You could have played that Springsteen tape in here, too (flickr/rockheim).

From Neojaponisme, we find this pretty bleak assessment of the electronics scene in that country. Dominant throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Sony, Sharp, and all the rest have fallen on hard times. And with Apple swallowing up a vast chunk of all the profit made from the sale of gadgets, the conglomerates that defined my childhood have been reduced to making parts for Apple's glitzy products.

2012 was one of the most disastrous years for the bloated electronics industry since its inception. Sharp, Panasonic, and Sony started the year off with bad news but thoughtful hopes -- selling off factories to Chinese investors, realigning product foci, and even looking to create new product lines! -- but ended up reporting losses totaling to ¥1.23 trillion ($15.3 billion). The massive investments failed to pay off, and now Sharp, the most cash strapped of the once-mighty giant manufacturers, looks increasingly likely to end up mostly a parts supplier for Apple. With Sharp supplying iPhone and iPad panels, Sony making the camera sensors, and a small army of smaller manufacturers making many other components, the Japanese electronics industry as a whole seems fated to lack compelling products of its own, forcing it to occupy the less glamorous and less profitable role as the world's ultra high-tech parts maker.Via Charlie Cheever

How-Not-To: This Holiday Season, Show Your Parents How to Break Their Computers

A 2013 resolution: I'm going to demonstrate how to screw up technologies safely.

Not like this (flickr/binarydreams).

It is a well-recognized feature of the holiday pilgrimage: We children pay homage and respect to our parents by fixing the problems we see in their information technology. We buy them new gizmos, too, and require them to learn how to 'Facetime' with grandkids or to get on Facebook to see pictures of the family. Point being, we ask our parents to figure out how to do new things all the time. And in many of those cases, we actually teach them how to do it: we lead the cursor around the screen and dictate hows and wherefores, while Bing Crosby plays in the background.What the Days After Christmas Feel Like

Total letdown. By which I mean, Sad Santa in the Surf.

A Santa at Panama City Beach (State Library and Archives of Florida).

If you'd like to wallow in your misery, I've included five sad piano tracks that you can play while you gaze at the depths of 2013.

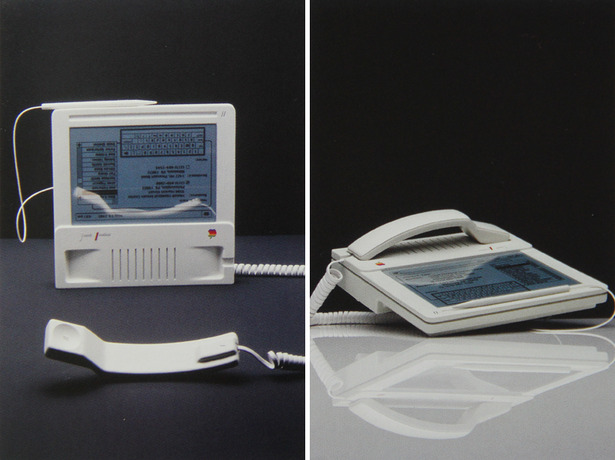

The Lost Apple 'MacPhone'

This thing is basically the centaur of gadgets.

Hartmut Esslinger via Design Boom

In the early 1980s, Frog Design founder Hartmut Esslinger had the freedom to create a new look and feel for Apple. In a new book excerpted on Designboom, he shows off his prototypes for what would become the defining Apple look in the pre-iPod era.

Among the old prototypes for what would become the Apple IIC and IIE, we find this strange contraption, the "Macphone." Part stylus-operated tablet, part (corded, landline?) telephone, there still isn't a gadget today that looks like it. And there may never be: the MacPhone is probably a dead branch on the technological evolutionary tree, despite its excellent handset shape.

UPDATE! VERY IMPORTANT UPDATE! I take it back. The MacPhone lives. Err. Lived. Mat Buchanan pointed out to me that Verizon marketed something like this thing in 2009 as the Verizon Hub. You can see for yourself what you think of it.

And reaching deep into my own memory vault, I remembered that a Chinese company at CES 2011 also had something like this on display, though I do not think it ever came to market, at least on this side of the Pacific.

Hartmut Esslinger via Design Boom

You Know What I Want to Do in 2013? Talk to My Television

A plea to TV makers in 2013: give me radically simply voice-control for changing channels.

Imagine doing this on your couch in front of your friends. And yes, you have to wear the sweater. Be recognized (Samsung)!

My old friend Mat Honan makes a good point about the recent NPD report about "smart televisions": they are horrible and no one likes them.I think I can explain all of this with a single thesis: smart TVs are the literal, biblical devil. (That may be overly broad. Perhaps they are merely demonic.) But the bottom line is that smart TVs typically have baffling interfaces that make the act of simply finding and watching your favorite stuff more difficult, not less.

Bruce Sterling on Why It Stopped Making Sense to Talk About 'The Internet' in 2012

Five simple reasons: Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft.

Bruce Sterling (flickr/webmink, with some fiddling).

Many people use, as a kind of shorthand, The Internet to mean a wide variety of things related to this series of tubes. The Internet could mean the culture made and distributed on the Internet, the LOLCATZ, memes, etc. ("The Internet loves this kind of stuff.") The Internet could mean the infrastructure itself, its speed and distribution. ("The Internet is so sloooow right now.") The Internet could mean the industry that builds it, the consumer and B2B companies that effectively own all the quasi-public spaces through which we traipse. ("The Internet wants to disintermediate blahblahblah.") And there are a thousand other times when we find it easier to say, "The Internet does" or "It feels like the Internet is" or whatever rather than attempt to identify the specific actors of the play.

And maybe that was helpful. Maybe in such a distributed system it makes sense to use "The Internet" as a stand-in for causal agents that seem to inhere in the network without belonging to any individual node. Maybe it's like a mob or a gatheration of starlings; the dynamic relationships between the individuals turn out to be more important than the things themselves.

But in 2012, that way of talking, if it was ever helpful, is no longer.

And there are five reasons for that: Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft. Now, when we say, "The Internet" or "smartphones" or "computers" we usually mean something shaped by one of these entities, or all of them.

At least that's how Bruce Sterling is thinking about things. In his annual conversation with Jon Lebkowsky on the WELL about the state of the world, he classed in "The Stacks," as he called them, with "some interest groups of 2013 who seem to be having a pretty good time."

Stacks. In 2012 it made less and less sense to talk about "the Internet," "the PC business," "telephones," "Silicon Valley," or "the media," and much more sense to just study Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft. These big five American vertically organized silos are re-making the world in their image.

If you're Nokia or HP or a Japanese electronics manufacturer, they stole all your oxygen. There will be a whole lot happening among these five vast entities in 2013. They never compete head-to-head, but they're all fascinated by "disruption."

What will the world that they create look like? Here's what I think: Your technology will work perfectly within the silo and with an individual stacks's (temporary) allies. But it will be perfectly broken at the interfaces between itself and its competitors.

That moment where you are trying to do something that has no reason not to work, but it just doesn't and there is no way around it without changing some piece of your software to fit more neatly within the silo?

That's gonna happen a lot: 2013 as the year of tactically broken bridges.

Who Was First in the Race to the Moon? The Tortoise

The tortoises in question (Energia.ru).

Offer: Gift a Signed Copy of Our Atlantic Tech Ebook

How We Think About Technology

The Atlantic Tech's how-to guide for producing meaningful, in-depth stories in a resource-starved, time-crunched media age.

One way to think about media, courtesy of the 1970s art/activist collective, Ant Farm (Alexis Madrigal).

Today, we released an anthology of this blog's best stories for a variety of ebook platforms. You can download it for free until the end of the year. We selected a few dozen stories that we think showcase what we're trying to do here out of the 1,500 posts we did in 2012.

And let's be honest: we're psyched about this project. I think we've developed distinctive ways of looking at the world. We do a different kind of writing from most of what you see on Techmeme or Google News.

I wrote an introduction to the book that attempts to explain how we think about technology and thank (some of) the people to whom we owe intellectual debts. It's reprinted here.

Perhaps it is our personal how-to guide for producing meaningful, in-depth stories in a resource-starved, time-crunched media age.

* * *

Thank you for downloading The Atlantic's Technology Channel anthology for 2012. We're proud of the work in here and hope you find stories that you love. [Note: You should really go download this anthology now.]

But I have to admit that this project began selfishly.

I wanted to see what we'd done on a daily basis assembled into one (semi-)coherent whole; I wanted to see how, over the course of the year, we'd shared our obsessions with readers and continued to grope toward a new understanding of technology.

That process really began when I launched the Technology Channel at the The Atlantic in 2010. Back then, I knew that I wanted to build a different kind of tech site. I wanted to write things that would last. My friend Robin Sloan, who you see pop up on the site now and again, has a way of talking about this. He says that "stock and flow" is the "master metaphor" for media today. "Flow is the feed. It's the posts and the tweets. It's the stream of daily and sub-daily updates that remind people that you exist," he's written. "Stock is the durable stuff. It's the content you produce that's as interesting in two months (or two years) as it is today. It's what people discover via search. It's what spreads slowly but surely, building fans over time."

To my mind, even the best tech blogs focus on "flow" for both constitutional and corporate reasons. They're fast, fun, smart, argumentative, hyperactive. Some of them do flow very well. And I knew we were not going to beat them at that game. But stock, that was something else. Stock was our game.

Looking at The Atlantic as a brand or an organizing platform or a mission, I see a possibility that verges on a responsibility to do things that resound over time. Resound. Things that keep echoing in your head long after the initial buzzing stops. Things that resonate beyond the news cycle. After all, we're old! Born in 1857 out of the fires of abolitionism, The Atlantic has survived because it's been willing to change just the right amount. It's responded to the demands of the market, but never let them fully hold sway. And in the best of cases, we changed the way our readers thought, challenged our own convictions, and laid down some of the essential reporting in American history. This may all sound like big talk, but we have to own this history, regardless of what the information marketplace looks like right now. Recognizing this history gives us a duty to provide journalism that stands up over time--no matter how it gets consumed.

But how to create stock in a blogging environment? It may sound crazy as a content strategy, but we developed a worldview: habits of mind, ways of researching, types of writing. Then, we used the news to challenge ourselves, to test what we thought we knew about how technology worked. Embedded in many stories in this volume, you can see us going back and forth with ourselves over the biggest issues in technology. How much can humans shape the tools they use? What is the relationship between our minds and the tools we think with, from spreadsheets to drones? What is the potential for manipulating biology? How do communications technologies structure the way ideas spread?

Delve into almost any technological system, and you'll see the complex networks of ideas, people, money, laws, and technical realities that come together to produce what we call Twitter or the cellphone or in vitro fertilization or the gun. This book is an attempt to document our forays into these networks, looking for the important nodes. This is a first-person enterprise, but we couldn't do it alone.

So, I'd like to thank the wide variety of people who have shaped the way we think. These are some of the ideas that we've been trying to synthesize, although obviously not the only ones.

To Jezebel's Lindy West, we owe thanks for this remarkable distillation of the technological condition: "Humanity isn't static--you can't just be okay with all development up until the invention of the sarong, and then declare all post-sarong technology to be 'unnatural,'" she wrote this year. "Sure, cavemen didn't have shoes. Until they invented fucking shoes!"

To Evgeny Morozov, we owe gratitude for the enumeration of the dangers of technocentrism. "Should [we] banish the Internet--and technology--from our account of how the world works?" he asked in October 2011. "Of course not. Material artifacts--and especially the products of their interplay with humans, ideas, and other artifacts--are rarely given the thoughtful attention that they deserve. But the mere presence of such technological artifacts in a given setting does not make that setting reducible to purely technological explanations." As Morozov prodded us consider, if Twitter was used in a revolution, is that a Twitter revolution? If Twitter was used in your most recent relationship, is that a Twitter relationship? Technology may be the problem or the solution, but that shouldn't and can't be our assumption. In fact, one of the most valuable kinds of technology reporting we can do is to show the precise ways that technology did or did not play the roles casually assigned to it.

We are indebted to the historian David Edgerton for providing proof, in The Shock of the Old, that technologies are intricately layered and mashed together. High and low technology mix. Old and new technology mix. The German army had 1.2 million horses in February of 1945. Fax machines are still popular in Japan. The QWERTY keyboard appears on the newest tablet computer. We need simple HVAC technology to make the most-advanced silicon devices. William Gibson's famous quote about the future, "The future is already here--it's just not very evenly distributed," should be seen as the Gibson Corollary to the Faulkner Principle, "The past is never dead. It's not even past."

To Stewart Brand and his buddies like J. Baldwin, we are thankful for cracking open outdated and industrial ways of thinking about technology, allowing themselves to imagine a "soft tech." They asked what it might mean to create technologies that were "alive, resilient, adaptive, maybe even loveable." They did not just say technology was bad, but tried to imagine how tech could be good. And in so doing, they opened up a narrow channel between technological and anti-technological excesses.

From the museum curator Suzanne Fischer and the philosopher Ivan Illich, we found ways of thinking about the importance of technology beyond market value. What if the point of tools is not to increase the efficiency of our world, but its, in Illich's phrase, conviviality? "Tools," he wrote, "foster conviviality to the extent to which they can be easily used, by anybody, as often or as seldom as desired, for the accomplishment of a purpose chosen by the user." Of course, these are ideals to aspire to. Ideals we may not even agree with or find too broad for our taste. But isn't it nice to have some ideals? We need measuring sticks not dominated in dollars.

We owe Matt Novak for his detailed dismantling of our nostalgic visions of the past. His work at Paleofuture lets us imagine decades' worth of solutions to today's still-pressing problems. His point is not that things are the same as they ever were. Because it's the details of these past visions that allow us to see how we've changed, not just technologically, but culturally.

What does all this add up to? A project to place people in the center of the story of technology. People as creators. People as users. People as pieces of cyborg systems. People as citizens. People make new technologies, and then people do novel things with them. But what happens then? That's what keeps us writing, and we hope what keeps you reading.

Thank you,

Alexis C. Madrigal

Oakland, California

Happy Holidays! Here's a Free Ebook of Our Best Stories From 2012

A free ebook of our best work just in time for the holidays. Makes a great gift for wordy nerds! And much cheaper than a Battlestar Galactica box set.

A robot Santa. Sorry, *the* robot Santa (flickr/lilspikey).

Dear Robot Santa,

I'm just writing to let you know that I don't need anything for Christmas (or Hanukkah). I got married this year, so I'm straight stocked on Calphalon and dinner plates. Netflix, my cat, and Twitter provide for all of my entertainment needs. And I already have too many shoes.

So, this year, we want to give something back to the great rucksack in the sky. We went through the roughly 1,500 posts we did this year and picked out just a few. They are our finest work. We rolled those up into an easy-to-read anthology that people can download and read on their platform of choice.

In addition to work from me, Megan Garber and Becca Rosen, you'll find stories by some of our regular contributors like Ross Andersen, Ian Bogost, Yoni Appelbaum, Sarah Rich, Suzanne Fischer, Howard Rheingold, Robinson Meyer, and Alexandra Samuel.

Oh, and it's free. (At least until the end of the year, when the price will rocket up to $1.99.) *

This is a gift from your loyal correspondents to the community. Thank you.

Thanks,

Alexis

P.S. If you want to read about why we did the book, I wrote an introduction that tries to explain what we do and how we do it.

If you want to read about *how* we did the book, I'll have a post for you tomorrow about the most excellent tools you can use to create ebooks these days.

We could not have completed the book without the gracious and amazing work of copy editors Janice Cane and Karen Ostergren, as well as the book's shepherds Geoff Gagnon, Betsy Ebersole, and Peter Elkins-Williams. We also want to thank our designer, Darhill Crooks, for taking a break from his magazine work to create the awesome cover you see right up there.

*Update: We seem to be experiencing a glitch and the price has shot up to $1.99 for the Kindle version earlier than planned. We are hoping to get this resolved (and bring the price back to free) shortly. Apologies and thank you for your patience.

The Christmas Card as Social Media

Don't worry: there'll be humblebrags all year round now!

A Christmas card (flickr/meanderingwa).

The number of Christmas cards appears to be dwindling, mailbox by mailbox, jolly Santa by red-nose reindeer. And there's something unnerving about that for some people. What will it mean if no one sends Christmas cards or letters? Nothing good, they'll tell you.

Nina Burleigh distills this sentiment for a nice essay in Time, pinning the blame for the decline on the ubiquity of social media in giving real-time access to one's friends and associates. "We already know exactly how they've fared in the past year, much more than could possibly be conveyed by any single Christmas card," Burleigh writes. "If a child or grandchild has been born to a former colleague or high school chum living across the continent, not only did I see it within hours on Shutterfly or Instagram or Facebook, I might have seen him or her take his or her first steps on YouTube. If a job was gotten or lost, a marriage made or ended, we have already witnessed the woe and joy of it on Facebook, email and Twitter."

Although the reason for the cards supposed decline is the rise in social interactions with one's people (sounds great?), the falling importance of Christmas cards remains, in Burleigh's mind, a bad omen.

"[T]he demise of the Christmas photo card saddens me. It portends the end of the U.S. Postal Service. It signals the day is near when writing on paper is non-existent. Finally, it is part of a decline of a certain quality of communication, one that involved delay and anticipation, forethought and reflection," Burleigh continues. "Opening these cards, the satisfaction wasn't just in the Peace on Earth greeting, but in the recognition that a distant friend or relative you hadn't heard from in a year was still thinking about you, and maybe sharing news about major events of the past 12 months."

But if you look even just a tiny bit deeper into the history of Christmas cards and letters, they cannot carry the weight Burleigh (and many others) want them to.

Take a look back at this article from 1978. It as already bemoaning that the salad days of Christmas cards were over! The 1960s were really the big growth period for cards. Why? "Back in those days, it was a lot more impersonal. Secretaries addressed their bosses' cards," the then-President of Hallmark said. "Now people may send fewer cards, but will put personal notes on them."

It wasn't long ago that the Christmas letter, specifically, was reviled, not celebrated. An older writer on HamptonRoads.com, who had not gotten the memo it was time to celebrate the golden hour of the form, commented, "Every year I get those letters, the ones where friends brag about how Junior graduated from Harvard, Sister married the CEO of a Fortune 500 company, Hubby got a promotion for the twentieth year in a row and the letter-writer was voted best Mom in the world."

Honestly, I'd always thought other people considered Christmas cards a necessary evil of maintaining reciprocal friendships with people who liked them. And to my mind, Christmas letters were a loathsome tradition sent into overdrive by photocopying machines and easy access to desktop publishing tools. And yet now we find sadness over the loss of this valuable form of literary output and emotional connection.

Even a pre-mainstream-Facebook article about practice of Christmas letter writing in the Christian Science Monitor had to begin with a defense:

Around Christmastime a couple of years ago, one of my friends ranted about how much he hated those holiday "brag letters" people send out each year. After making a mental note never to send him one in the future, I began to wonder what it is that makes people so irate about the good fortune of others.

I actually like hearing about what the people who lived down the street from me 20 years ago are up to. Sure, it initially takes some remembering to figure out who they are and why they're sending me that card, but if it weren't for the annual tradition, it would be easy to lose touch.

What's the logic here? Someone keeps your name in a database Rolodex, dashes off a note or prints another copy of a letter once a year, and that's supposed to be some form of deep, analog connection?

So, what I find most fascinating about the decline of Christmas missives and its attendant celebration is that we are willing to imbue them with the power to connect us together, while denying that power to newer inventions.

Imagine social media's critics casting their eyes on the enterprise of holiday-card writing:

- Holiday cards are a stand in for real face-to-face interaction, allowing people to present a simulacra of emotional connection that hollows out the real thing.

- The Christmas card list was the original "friend" list.

- Holiday cards, in that you could count them, led to an early quantification of social relationships. "How many Christmas cards are on *your* mantle?"

- Christmas letters allowed people to cherrypick from their lives, allowing them to misrepresent the "real" person behind the letter.

- Holiday cards were mostly maudlin crap wishing people "Peace on Earth" as if that could make any real difference for stopping wars.

- Christmas letters mostly contained the mundane details about people trips, diseases, trumped up accomplishments, and hallucinatory future plans.

- Holiday cards merely serve to enrich the card companies.

- Holiday cards are expensive for some people to purchase and send, reinforcing societal inequalities.

- Holiday cards often served to shore up business networks and social alliances rather than to communicate real feelings.

- The labor of holiday cards fell disproportionately to women, who were given one more laborious task and judged more harshly than men if their efforts fell short.

And on and on and on.

Burleigh's an interesting writer and I don't think we can chalk up her Christmas card desires to simple nostalgia. There's something about the way we talk about technology and change that makes it seem like there are these discontinuous eras where -- SNAP! -- the whole world becomes different. And as we try to put things back together from this rhetorical future shock, the timeline gets jumbled. Memories of Christmas letters from the 1960s expressing timeless sentiments get grafted onto 1980s designs, which are pictured with 1970s stamps. Somewhere, there is the sound of a dot matrix printer putting ink on paper.

This kind of remembering is something weirder than nostalgia. It's not looking back at one sunny era; it's a crazy mashup of varied history and technologies that create a chimera we can compare, generally, to Twitter or Facebook. That's how Christmas cards somehow come to stand in for the existence of "writing on paper." We need a symbol of the past to compare with these symbols of the present. That's how we blow our own minds about how fast the world is changing.

Here's my optimistic thought, though: What if we stop thinking about "the way technology changes our lives" as less sudden. What if we look for continuities rather than breaks?

For one, the death of the Christmas card is at least slightly exaggerated. The numbers are a bit confusing. First class mail around Christmas has fallen roughly 25 percent off its peak in 2006, according to the USPS. And a marketing firm suggests that fewer people are buying Christmas cards.

On the other hand, despite the drop, the USPS will still send 2 billion pieces of holiday mail a year. And the companies that make Christmas cards are doing OK, too. "Is Facebook putting card sending out of business?" asked Kathy Krassner, a spokesperson for the Greeting Card Association. "Truly, it's helped. A lot of people, myself included, have reestablished connections with people that I would have never found. It's helped establish more connections."

The precipitous drop for Christmas mailings came in the wake of the financial crisis and the near destruction of the global economy, not with rising Facebook penetration rates. The card industry's statistics back that up. The Greeting Card Association estimates that 1.6 billion Christmas cards will be purchased this year, a small increase from last year. A report from the research firm, IBISWorld, anticipates that cards and postage will be the highest they've been in five years -- $3.17 billion total. And finally, the card industry's biggest player, Hallmark, has had revenues of around $4.0 billion dollars since the mid-2000s, without much growth or decline.

Second, beyond the physical form of these cards, the spirit of Christmasness, of holidayness only grows more pervasive. No matter what time of the year, people now write contemplative letters with weird formatting to an ill-defined audience of "friends"; these are Christmas letters, whether Santa is coming down the chimney or not. There are reindeer horns on pugs in July. And humblebrags about promotions in April. There are dating updates in November. And you can disclose that you were voted mother of the year any damn day you please.

For good or for ill, perhaps we're seeing not the death of the holiday card and letter, but its rebirth as a rhetorical mode. Confessional, self-promotional, hokey, charming, earnest, technically honest, introspective, hopey-changey: Oh, Christmas Card, you have gone open-source and conquered us all.

Instagram Explains Itself, Basically Confirms the Fear That I Had

Instagram is providing a peek into the future of advertising. Let's see if you like it.

An Instagram of a restaurant that I would happily advertise.

When Instagram changed its terms of service, I envisioned a scenario where the company would use my photos near some place to advertise that place to my friends. Today, in response to some users' negative responses, co-founder Kevin Systrom put out this vision for his company's future business model:

Let's say a business wanted to promote their account to gain more followers and Instagram was able to feature them in some way. In order to help make a more relevant and useful promotion, it would be helpful to see which of the people you follow also follow this business. In this way, some of the data you produce -- like the actions you take (eg, following the account) and your profile photo -- might show up if you are following this business.

How is this different from my scenario? Well, in Systrom's scenario, you've followed the brand explicitly. In mine, they've extracted your "implicit" fandom. But in both cases, your information will be used to help sell your friends on a business.

And I admit, that is a big difference.

On the other hand, what is to stop Instagram from advancing from their scenario to mine? Precisely nothing, as the terms of service lay out so nicely:

To help us deliver interesting paid or sponsored content or promotions, you agree that a business or other entity may pay us to display your username, likeness, photos (along with any associated metadata), and/or actions you take, in connection with paid or sponsored content or promotions, without any compensation to you.

If all they're after is profile photos, then why specifically reserve the right to photos and associated metadata?

Take this scenario: You go out on a date and take a photo in front of a restaurant. Instagram extracts the restaurant name (say, Hard Rock Cafe) and uses that information and/or photograph to sell that place to your Instagram followers who open up the app when they are near that location.

Our business editor, Derek Thompson, when I laid out this scenario, said to me, "That is really assuming a lot about the technology and projecting way down the line."

But I don't think it is. After all, it's easy to match up location data with places that you go. And even if you scrub the location data, for many brands, it's possible to do machine vision on their logos. This is what the Google Maps VP told me about this very topic (emphasis mine):

Google Maps VP Brian McClendon put it like this: "We can actually organize the world's physical written information if we can OCR it and place it," McClendon said. "We use that to create our maps right now by extracting street names and addresses, but there is a lot more there."

More like what? "We already have what we call 'view codes' for 6 million businesses and 20 million addresses, where we know exactly what we're looking at," McClendon continued. "We're able to use logo matching and find out where are the Kentucky Fried Chicken signs ... We're able to identify and make a semantic understanding of all the pixels we've acquired. That's fundamental to what we do."

Granted, Google is Google. But Instagram is Facebook, no? Are we really betting that they can't come up "a semantic understanding of all the pixels we've acquired"? Of course, the we in McClendon's quote with Google, whereas the we in my reformulation is Instagram's users. And that's the rub.

Keep in mind, too, that Facebook uses the contents of your messages to sell you advertising. If you mention you got engaged in wall posts, BOOM, wedding service ads. They even have to have rules, internally, about how long they should allow people to target those who have talked about engagements. This is the road that Instagram is starting down.

There are ways that Instagram could roll out a business model without doing this kind of stuff. Users could pay (or even just pay to opt out), as I suggested yesterday. Wired's Mat Honan laid out a few more options:

There are a lot of other ways to make money. Sell an ad in the stream. Sell an ad on individual users' pages. Sell an ad against search results, and another for tags that relate to upcoming events. Offer "pro" features -- like special filters or promoted profiles.

To which I say, yeah!

But also, even within the advertising scenario that Systrom is laying out, Instagram could make things a little better for its users. The terms of service could simply take out that little claim on your "photos (along with any associated metadata)." Honestly, you take that out, and I'm feeling OK with the rest of it. Use my likeness, use my actions following brands, fine. But leave the actual contents of my content out of it.

And maybe they will. We'll have to wait and see what the actual changes look like, but Systrom did add in his note to users, "The language we proposed also raised question about whether your photos can be part of an advertisement. We do not have plans for anything like this and because of that we're going to remove the language that raised the question."

I don't trust what companies tell us about their "plans," but I'd love that language to disappear.

More at the Atlantic

Alexis C. Madrigal's Archive

Writers

-

Alexis C. Madrigal

Alexis C. Madrigal

The Coolest-Looking Dolphin in the World

-

James Fallows

James Fallows

Why I Get More Than One Newspaper

-

Derek Thompson

Derek Thompson

BuzzFeed, Andrew Sullivan, and the Future of…

-

Jeffrey Goldberg

Jeffrey Goldberg

'Women Who Own Assault Weapons Have Tiny Penises'

-

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ta-Nehisi Coates

The Hollywood America Deserves

-

Robert Wright

Robert Wright

Podcasts to Try in 2013

-

Steve Clemons

Steve Clemons

Reading Tea Leaves of Political Appointments Not…

-

Garance Franke-Ruta

Garance Franke-Ruta

Leave 'Thelma & Louise' Alone

-

Clive Crook

Clive Crook

Two Book Recommendations

Subscribe Now

SAVE 65%! 10 issues JUST $2.45 PER COPY

Newsletters

Sign up to receive our free newsletters