How a dream team of engineers from Facebook, Twitter, and Google built the software that drove Barack Obama's reelection

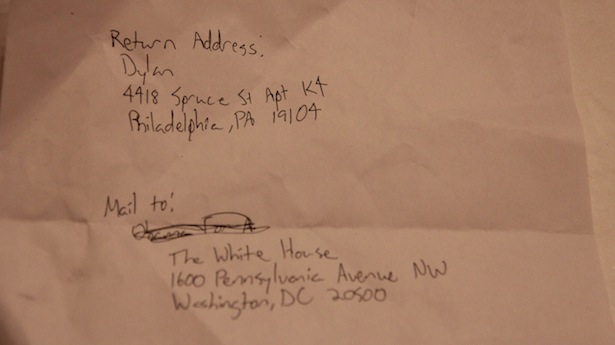

Three members of Obama's tech team, from left to right: Harper Reed, Dylan Richard, and Mark Trammell (Photo by Daniel X. O'Neil).

The Obama campaign's technologists were tense and tired. It was game day and everything was going wrong.

Josh Thayer, the lead engineer of Narwhal, had just been informed that they'd lost another one of the services powering their software. That was bad: Narwhal was the code name for the data platform that underpinned the campaign and let it track voters and volunteers. If it broke, so would everything

else.

They were talking with people at Amazon Web Services, but all they knew was that they had packet loss. Earlier that day, they lost their databases, their

East Coast servers, and their memcache clusters. Thayer was ready to kill Nick Hatch, a DevOps engineer who was the official bearer of bad news. Another of

their vendors, PalominoDB, was fixing databases, but needed to rebuild the replicas. It was going to take time, Hatch said. They didn't have time.

They'd been working 14-hour days, six or seven days a week, trying to reelect the president, and now everything had been broken at just the wrong

time. It was like someone had written a Murphy's Law algorithm and deployed it at scale.

They'd been working 14-hour days, six or seven days a week, trying to reelect the president, and now everything had been broken at just the wrong time.

And that was the point. "Game day" was October 21. The election was still 17 days away, and this was a live action role playing (LARPing!) exercise that

the campaign's chief technology officer, Harper Reed, was inflicting on his team. "We worked through every possible disaster situation," Reed said. "We did

three actual all-day sessions of destroying everything we had built."

Hatch was playing the role of dungeon master, calling out devilishly complex scenarios that were designed to test each and every piece of their system as

they entered the exponential traffic-growth phase of the election. Mark Trammell, an engineer who Reed hired after he left Twitter, saw a couple game days.

He said they reminded him of his time in the Navy. "You ran firefighting drills over and over and over, to make sure that you not just know what you're

doing," he said, "but you're calm because you know you can handle your shit."

The team had elite and, for tech, senior talent -- by which I mean that most of them were in their 30s -- from Twitter, Google, Facebook, Craigslist, Quora, and

some of Chicago's own software companies such as Orbitz and Threadless, where Reed had been CTO. But even these people, maybe *especially* these people,

knew enough about technology not to trust it. "I think the Republicans fucked up in the hubris department," Reed told me. "I know we had the best

technology team I've ever worked with, but we didn't know if it would work. I was incredibly confident it would work. I was betting a lot on it. We had

time. We had resources. We had done what we thought would work, and it still could have broken. Something could have happened."

In fact, the day after the October 21 game day, Amazon services -- on which the whole campaign's tech presence was built -- went down. "We didn't have any

downtime because we had done that scenario already," Reed said. Hurricane Sandy hit on another game day, October 29, threatening the campaign's whole East

Coast infrastructure. "We created a hot backup of all our applications to US-west in preparation for US-east to go down hard," Reed said.

"We knew what to do," Reed maintained, no matter what the scenario was. "We had a runbook that said if this happens, you do this, this, and this. They did

not do that with Orca."

THE NEW CHICAGO MACHINE vs. THE GRAND OLD PARTY

Orca was supposed to be the Republican answer to Obama's perceived tech advantage. In the days leading up to the election, the Romney campaign pushed its

(not-so) secret weapon as the answer to the Democrats' vaunted ground game. Orca was going to allow volunteers at polling places to update the Romney

camp's database of voters in real time as people cast their ballots. That would supposedly allow them to deploy resources more efficiently and wring every

last vote out of Florida, Ohio, and the other battleground states. The product got its name,

a Romney spokesperson told NPR PBS

, because orcas are the only known predator of the one-tusked narwhal.

Orca was not even in the same category as Narwhal. It was like the Republicans were touting the iPad as a Facebook killer.

The billing the Republicans gave the tool confused almost everyone inside the Obama campaign. Narwhal wasn't an app for a smartphone. It was the

architecture of the company's sophisticated data operation. Narwhal unified what Obama for America knew about voters, canvassers, event-goers, and

phone-bankers, and it did it in real time. From the descriptions of the Romney camp's software that were available then and now, Orca was not even in the

same category as Narwhal. It was like touting the iPad as a Facebook killer, or comparing a GPS device to an engine. And besides, in the scheme of a

campaign, a digitized strike list is cool, but it's not, like, a gamechanger. It's just a nice thing to have.

So, it was with more than a hint of schadenfreude that Reed's team hear that Orca crashed early on election day. Later reports posted by rank-and-file volunteers describe chaos descending on the polling locations as only a fraction

of the tens of thousands of volunteers organized for the effort were able to use it properly to turn out the vote.

Of course, they couldn't snicker too loudly. Obama's campaign had created a similar app in 2008 called Houdini. As detailed in Sasha Issenberg's

groundbreaking book, The Victory Lab, Houdini's rollout went great until about 9:30am Eastern on the day of the election. Then it crashed in much the

same way Orca did.

In 2012, Democrats had a new version, built by the vendor, NGP VAN. It was called Gordon, after the man who killed Houdini. But the 2008 failure, among

other needs, drove the 2012 Obama team to bring technologists in-house.

With election day bearing down on them, they knew they could not go down. And yet they had to accommodate much more strain on the systems as interest in

the election picked up toward the end, as it always does. Mark Trammell, who worked for Twitter during its period of exponential growth, thought it would

have been easy for the Obama team to fall into many of the pitfalls that the social network did back then. But while the problems of scaling both

technology and culture quickly might have been similar, the stakes were much higher. A fail whale (cough) in the days leading up to or on November 6 would

have been neither charming nor funny. In a race that at least some people thought might be very close, it could have cost the President the election.

And of course, the team's only real goal was to elect the President. "We have to elect the President. We don't need to sell our software to Oracle," Reed

told his team. But the secondary impact of their success or failure would be to prove that campaigns could effectively hire and deploy top-level

programming talent. If they failed, it would be evidence that this stuff might be best left to outside political technology consultants, by whom the arena

had long been handled. If Reed's team succeeded, engineers might become as enshrined in the mechanics of campaigns as social-media teams already are.

We now know what happened. The grand technology experiment worked. So little went wrong that Trammell and Reed even had time to cook up a little pin to

celebrate. It said, "YOLO," short for "You Only Live Once," with the Obama Os.

When Obama campaign chief Jim Messina signed off on hiring Reed, he told him, "Welcome to the team. Don't fuck it up." As Election Day ended and the dust

settled, it was clear: Reed had not fucked it up.

The campaign had turned out more volunteers and gotten more donors than in 2008. Sure, the field organization was more entrenched and experienced, but the

difference stemmed in large part from better technology. The tech team's key products -- Dashboard, the Call Tool, the Facebook Blaster, the PeopleMatcher,

and Narwhal -- made it simpler and easier for anyone to engage with the President's reelection effort.

The nerds shook up an ossifying Democratic tech structure and the politicos taught the nerds a thing or two about stress, small-p politics, and the meaning of life.

But it wasn't easy. Reed's team came in as outsiders to the campaign and by most accounts, remained that way. The divisions among the tech, digital, and

analytics team never quite got resolved, even if the end product has salved the sore spots that developed over the stressful months. At their worst, in

early 2012, the cultural differences between tech and everybody else threatened to derail the whole grand experiment.

By the end, the campaign produced exactly what it should have: a hybrid of the desires of everyone on Obama's team. They raised hundreds of millions of

dollars online, made unprecedented progress in voter targeting, and built everything atop the most stable technical infrastructure of any presidential

campaign. To go a step further, I'd even say that this clash of cultures was a good thing: The nerds shook up an ossifying Democratic tech structure and

the politicos taught the nerds a thing or two about stress, small-p politics, and the significance of elections.

YOLO: MEET THE OBAMA CAMPAIGN'S CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER

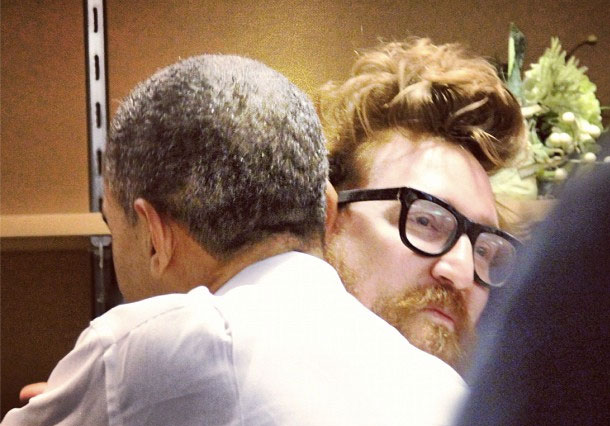

The President hugging Harper Reed as shown on his Instagram feed.

If you're a nerd, Harper Reed is an easy guy to like. He's brash and funny and smart. He gets you and where you came from. He, too, played with computers

when they weren't cool, and learned to code because he just could not help himself. You could call out nouns, phenomena, and he'd be right there with you:

BBS, warez, self-organizing systems, Rails, the quantified self, Singularity. He wrote his first programs at age seven, games that his mom typed into their

Apple IIC. He, too, has a memory that all nerds share: Late at night, light from a chunky monitor illuminating his face, fingers flying across a keyboard,

he figured something out.

TV news segments about cybersecurity might look lifted straight from his memories, but the b-roll they shot of darkened rooms and typing hands could not convey the sense

of exhilaration he felt when he built something that works. Harper Reed got the city of Chicago to create an open and real-time feed of its transit data

by reverse engineering how they served bus location information. Why? Because it made his wife Hiromi's commute a little easier. Because it was fun to

extract the data from the bureaucracy and make it available to anyone who wanted it. Because he is a nerd.

Yet Reed has friends like the manager of the hip-hop club Empire who, when we walk into the place early on the Friday after the election, says, "Let me

grab you a shot." Surprisingly, Harper Reed is a chilled vodka kind of guy. Unsurprisingly, Harper Reed read Steven Levy's Hackers as a kid.

Surprisingly, the manager, who is tall and handsome with rock-and-roll hair flowing from beneath a red beanie, returns to show Harper photographs of his

kids. They've known each other for a long while. They are really growing up.

As the night rolls on, and the club starts to fill up, another friend approached us: DJ Hiroki, who was spinning that night. Harper Reed knows the DJ. Of

course. And Hiroki grabs us another shot. (At this point I'm thinking, "By the end of the night, either I pass out or Reed tells me something good.") Hiroki's been DJing at Empire for years, since Harper Reed was the crazy guy you can see on his public Facebook photos. In one shot from

2006, a skinny Reed sits in a bathtub with a beer in his hand, two thick band tattoos running across his chest and shoulders. He is not wearing any

clothes. The caption reads, "Stop staring, it's not there i swear!" What makes Harper Reed different isn't just that the photo exists, but that he kept it public during the election.

He may be like you, but he also juggles better than you, and is wilder than you, more fun than you, cooler than you.

Yet if you've spent a lot of time around tech people, around Burning Man devotees, around startups, around San Francisco, around BBSs, around Reddit, Harper

Reed probably makes sense to you. He's a cool hacker. He gets profiled by Mother Jones even though he couldn't talk with Tim Murphy, their reporter. He supports open source. He likes Japan. He says fuck a lot. He goes to hipster bars that serve vegan

Mexican food, and where a quarter of the staff and clientele have mustaches.

He may be like you, but he also juggles better than you, and is wilder than you, more fun than you, cooler than you. He's what a king of the nerds really looks like. Sure, he might

grow a beard and put on a little potbelly, but he wouldn't tuck in his t-shirt. He is not that kind of nerd. Instead, he's got plugs in his ears and a

shock of gloriously product-mussed hair and hipster glasses and he doesn't own a long-sleeve dress shirt, in case you were wondering.

"Harper is an easy guy to underestimate because he looks funny. That might be part of his brand," said Chris Sacca, a well-known Silicon Valley venture

capitalist and major Obama bundler who brought a team of more than a dozen technologists out for an Obama campaign hack day.

Reed, for his part, has the kind of self-awareness that faces outward. His self-announced flaws bristle like quills. "I always look like a fucking idiot,"

Reed told me. "And if you look like an asshole, you have to be really good."

It was a lesson he learned early out in Greeley, Colorado, where he grew up. "I had this experience where my dad hired someone to help him out because his

network was messed up and he wanted me to watch. And this was at a very unfortunate time in my life where I was wearing very baggy pants and I had a

Marilyn Manson shirt on and I looked like an asshole. And my father took me aside and was like, 'Why do you look like an asshole?' And I was like, 'I don't

know. I don't have an answer.' But I realized I was just as good as the guys fixing it," Reed recalled. "And they didn't look like me and I didn't look

like them. And if I'm going to do this, and look like an idiot, I have to step up. Like if we're all at zero, I have to be at 10 because I have this stupid

mustache."

And in fact, he may actually be at 10. Sacca said that with technical people, it's one thing to look at their resumes and another to see how they are viewed among their peers. "And it was amazing how many incredibly well regarded hackers that I follow on Twitter rejoiced and celebrated

[when Reed was hired]," Sacca said. "Lots of guys who know how to spit out code, they really bought that."

By the time Sacca brought his Silicon Valley contingent out to Chicago, he called the technical team "top notch." After all, we're talking about a group of

people who had Eric Schmidt sitting in with them on Election Day. You had to be good. The tech world was watching.

Terry Howerton, the head of the Illinois Technology Association and a frank observer of Chicago's tech scene, had only glowing things to say about Reed.

"Harper Reed? I think he's wicked smart," Howerton said. "He knows how to pull people together. I think that was probably what attracted the rest of the

people there. Harper is responsible for a huge percentage of the people who went over there."

Reed's own team found their co-workers particularly impressive. One testament to that is several startups might spin out of the connections people made at

the OFA headquarters, such as Optimizely, a tool for website A/B testing, which spun out of Obama's 2008

bid. (Sacca's actually an investor in that one, too.)

"A CTO role is a weird thing," said Carol Davidsen, who left Microsoft to become the product manager for Narwhal. "The primary responsibility is getting

good engineers. And there really was no one else like him that could have assembled these people that quickly and get them to take a pay cut and move to

Chicago."

And yet, the very things that make Reed an interesting and beloved person are the same things that make him an unlikely pick to become the chief technology

officer of the reelection campaign of the President of the United States. Political people wear khakis. They only own long-sleeve dress shirts. Their old

photos on Facebook show them canvassing for local politicians and winning cross-country meets.

I asked Michael Slaby, Obama's 2008 chief technology officer, and the guy who hired Harper Reed this time around, if it wasn't risky to hire this wild guy

into a presidential campaign. "It's funny to hear you call it risky, it seems obvious to me," Slaby said. "It seems crazy to hire someone like me as CTO

when you could have someone like Harper as CTO."

THE NERDS ARE INSIDE THE BUILDING

The strange truth is that campaigns have long been low-technologist, if not low-technology, affairs. Think of them as a weird kind of niche startup and you

can see why. You have very little time, maybe a year, really. You can't afford to pay very much. The job security, by design, is nonexistent. And even

though you need to build a massive "customer" base and develop the infrastructure to get money and votes from them, no one gets to exit and make a bunch of

money. So, campaign tech has been dominated by people who care about the politics of the thing, not the technology of the thing. The websites might have

looked like solid consumer web applications, but they were not under the hood.

For all the hoopla surrounding the digital savvy of President Obama's 2008 campaign, and as much as everyone I spoke with loved it, it was not as heavily

digital or technological as it is now remembered. "Facebook was about one-tenth of the size that it is now. Twitter was a nothing burger for the campaign. It

wasn't a core or even peripheral part of our strategy," said Teddy Goff, Digital Director of Obama for America and a veteran of both campaigns. Think about the killer tool of that campaign, my.barackobama.com; It borrowed the my from MySpace.

Sure, the

'08 campaign had Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes, but Hughes was the spokesperson for the company, not its technical guy. The '08 campaigners, Slaby told

me, had been "opportunistic users of technology" who "brute forced and baling wired" different pieces of software together. Things worked (most of the

time), but everyone, Slaby especially, knew that they needed a more stable platform for 2012.

In 2008, Facebook was about one-tenth of the size that it is now. Twitter was a nothing burger for the campaign. It wasn't a core or even peripheral part of the strategy.

Campaigns, however, even Howard Dean's famous 2004 Internet-enabled run at the Democratic nomination, did not hire a bunch of technologists. Though they

hired a couple, like Clay Johnson, they bought technology from outside consultants. For 2012, Slaby wanted to change all that. He wanted dozens of

engineers in-house, and he got them.

"The real innovation in 2012 is that we had world-class technologists inside a campaign," Slaby told me. "The traditional technology stuff inside campaigns

had not been at the same level." And yet the technologists, no matter how good they were, brought a different worldview, set of personalities, and

expectations.

Campaigns are not just another Fortune 500 company or top-50 website. They have their own culture and demands, strange rigors and schedules. The deadlines

are hard and the pressure would be enough to press the t-shirt of even the most battle-tested startup veteran.

To really understand what happened behind the scenes at the Obama campaign, you need to know a little bit about its organizational structure.

Tech was Harper Reed's domain. "Digital" was Joe Rospars' kingdom; his team was composed of the people who sent you all those emails, designed some of the

consumer-facing pieces of BarackObama.com, and ran the campaigns' most-excellent accounts on Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, video, and the like. Analytics was

run by Dan Wagner, and those guys were responsible for coming up with ways of finding and targeting voters they could persuade or turn out. Jeremy Bird ran

Field, the on-the-ground operations of organizing voters at the community level that

many consider Obama's secret sauce

. The tech for the campaign was supposed to help the Field, Analytics, and Digital teams do their jobs better. Tech, in a campaign or

at least this campaign or perhaps any successful campaign, has to play a supporting role. The goal was not to build a product. The goal was to reelect the President. As Reed put it, if the campaign were Moneyball, he wouldn't be

Billy Beane, he'd be "Google Boy."

There's one other interesting component to the campaign's structure. And that's the presence of two big tech vendors interfacing with the various teams --

Blue State Digital and NGP Van. The most obvious is the firm that Rospars, Jascha Franklin-Hodge, and Clay Johnson co-founded, Blue State Digital. They're

the preeminent progressive digital agency, and a decent chunk -- maybe 30 percent -- of their business comes from providing technology to campaigns. Of

course, BSD's biggest client was the Obama campaign and has been for some time. BSD and Obama for America were and are so deeply enmeshed, it would be

difficult to say where one ended and the other began. After all, both Goff and Rospars, the company's principals, were paid staffers of the Obama campaign.

And yet between 2008 and 2012, BSD was purchased by WPP, one of the largest ad agencies in the world. What had been an obviously progressive organization

was now owned by a huge conglomerate and had clients that weren't other Democratic politicians.

One other thing to know about Rospars, specifically: "He's the Karl Rove of the Internet."

One other thing to know about Rospars, specifically: "He's the Karl Rove of the Internet," someone who knows him very well told me. What Rove was to direct mail -- the undisputed king of the medium -- Rospars is to email. He and Goff are the

brains behind Obama's unprecedented online fundraising efforts. They know what they were doing and had proven that time and again.

The complex relationship between BSD and the Obama campaign adds another dimension to the introduction of an inside team of technologists. If all campaigns

started bringing their technology in house, perhaps BSD's tech business would begin to seem less attractive, particularly if many of the tools that such an

inside team created were developed as open source products.

So, perhaps the tech team was bound to butt heads with Rospars' digital squad. Slaby would note, too, that the organizational styles of the two operations

were very different. "Campaigns aren't traditionally that collaborative," he said. "Departments tend to be freestanding. They are organized kind of like

disaster response -- siloed and super hierarchical so that things can move very quickly."

Looking at it all from the outside, both the digital and tech teams had really good, mission-oriented reasons for wanting their way to carry the day. The

tech team could say, "Hey, we've done this kind of tech before at larger scale and with more stability than you've ever had. Let us do this." And the

digital team could say, "Yeah, well, we elected the president and we know how to win, regardless of the technology stack. Just make what we ask for."

The way that the conflict played out was over things like the user experience on the website. Jason Kunesh was the director of UX for the tech team. He had

many years of consulting under his belt for big and small companies like Microsoft and LeapFrog. He, too, from an industry perspective knew what he was

doing. So, he ran some user interrupt tests on the website to determine how people were experiencing www.barackobama.com. What he found was that the website wasn't even trying to make a go at persuading voters.

Rather, everyone got funneled into the fundraising "trap." When he raised that issue with Goff and Rospars, he got a response that I imagine was something

like, "Duh. Now STFU," but perhaps in more words. And from the Goff/Rospars perspective, think about it: the system they'd developed could raise $3 million

*from a single email.* The sorts of moves they had learned how to make had made a difference of tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars. Why was this

Kunesh guy coming around trying to tell them how to run a campaign?

From Kunesh's perspective, though, there was no reason to think that you had to run this campaign the same as you did the last one. The outsider status

that the team both adopted and had applied to them gave them the right to question previous practices.

Tech sometimes had difficulty building what the Field team, a hallowed group within the campaign's world, wanted. Most of that related to the way that they

launched Dashboard, the online outreach tool. If you look at Dashboard at the end of the campaign, you see a beautifully polished product that let you

volunteer any way you wanted. It's secure and intuitive and had tremendously good uptime as the campaign drew to a close.

But that wasn't how the first version of Dashboard looked.

The tech team's plan was to roll out version 1 with a limited feature set, iterate, roll out version 2, iterate, and so on and so forth until the software

was complete and bulletproof. Per Kunesh's telling, the Field people were used to software that looked complete but that was unreliable under the hood. It

looked as if you could do the things you needed to do, but the software would keep falling down and getting patched, falling down and getting patched, all the

way through a campaign. The tech team did not want that. They might be slower, but they were going to build solid products.

In the movie version of the campaign, there's probably a meeting where I'm about to get fired and I throw myself on the table

Reed's team began to trickle into Chicago beginning in May of 2011. They promised, over-optimistically, that they'd release a version of Dashboard just a

few months after the team arrived. The first version was not impressive. "August 29, 2011, my birthday, we were supposed to have a prototype out of

Dashboard, that was going to be the public launch," Kunesh told me. "It was freaking horrible, you couldn't show it to anyone. But I'd only been there 13

weeks and most of the team had been there half that time."

As the tech team struggled to translate what people wanted into usable software, trust in the tech team -- already shaky -- kept eroding. By Februrary of

2012, Kunesh started to get word that people on both the digital and field teams had agitated to pull the plug on Dashboard and replace the tech team with

somebody, anybody, else.

"A lot of the software is kind of late. It's looking ugly and I go out on this Field call," Kunesh remembered. "And people are like, 'Man, we should fire

your bosses man... We gotta get the guys from the DNC. They don't know what the hell you're doing.' I'm sitting there going, 'I'm gonna get another

margarita.'"

While the responsibility for their early struggles certainly falls to the tech team, there were mitigating factors. For one, no one had ever done what they were

attempting to do. Narwhal had to connect to a bunch of different vendors' software, some of which turned out to be surprisingly arcane and difficult. Not

only that, but there were differences in the way field offices in some states did things and how campaign HQ thought they did things. Tech wasted time

building things that it turned out people didn't need or want.

"In the movie version of the campaign, there's probably a meeting where I'm about to get fired and I throw myself on the table," Slaby told me. But in

reality, what actually happened was Obama's campaign chief Jim Messina would come by Slaby's desk and tell him, "Dude, this has to work." And Slaby would

respond, "I know. It will," and then go back to work.

In fact, some shakeups were necessary. Reed and Slaby sent some product managers packing and brought in more traditional ones like former Microsoft PM

Carol Davidsen. "You very much have to understand the campaign's hiring strategy: 'We'll hire these product managers who have campaign experience, then

hire engineers who have technical experience -- and these two worlds will magically come together.' That failed," Davidsen said. "Those two groups of people

couldn't talk to each other."

Then, in the late spring, all the products that the tech team had been promising started to show up. Dashboard got solid. You didn't have to log in a bunch

of times if you wanted to do different things on the website. Other smaller products rolled out. "The stuff we told you about for a year is actually

happening," Kunesh recalled telling the Field team. "You're going to have one login and have all these tools and it's all just gonna work."

Perhaps most importantly, Narwhal really got on track, thanks no doubt to Davidsen's efforts as well as Josh Thayer's, the lead engineer who arrived in

April. What Narwhal fixed was a problem that's long plagued campaigns. You have all this data coming in from all these places -- the voter file, various

field offices, the analytics people, the website, mobile stuff. In 2008, and all previous races, the numbers changed once a day. It wasn't real-time. And

the people looking to hit their numbers in various ways out in the field offices -- number of volunteers and dollars raised and voters persuaded -- were used

to seeing that update happen like that.

But from an infrastructure level, how much better would it be if you could sync that data in real time across the entire campaign? That's what Narwhal was

supposed to do. Davidsen, in true product-manager form, broke down precisely how it all worked. First, she said, Narwhal wasn't really one thing, but

several. Narwhal was just an initially helpful brand for the bundle of software.

In reality, it had three components. "One is vendor integration: BSD, NGP, VAN [the latter two companies merged in 2010]. Just getting all of that data

into the system and getting it in real time as soon as it goes in one system to another," she said. "The second part is an API portion. You don't want a

million consumers getting data via SQL." The API allowed people to access parts of the data without letting them get at the SQL database on the backend. It

provided a safe way for Dashboard, the Call Tool (which helped people make calls), and the Twitter Blaster to pull data. And the last part was the

presentation of the data that was in the system. While the dream had been for all applications to run through Narwhal in real time, it turned out that

couldn't work. So, they split things into real-time applications like the Call Tool or things on the web. And then they provided a separate way for the

Analytics people, who had very specific needs, to get the data in a different form. Then, whatever they came up with was fed back into Narwhal.

It's just change management. It's not complicated; it's just hard.

By the end, Davidsen thought all the teams' relationships had improved, even before Obama's big win. She credited a weekly Wednesday drinking and hanging

out session that brought together all the various people working on the campaign's technology. By the very end, some front-end designers who were

technically on the digital team had embedded with the tech squad to get work done faster. Tech might not have been fully integrated, but it was fully

operational. High fives were in the air.

Slaby, with typical pragmatism, put it like this. "Our supporters don't give a shit about our org chart. They just want to have a meaningful experience. We

promise them they can play a meaningful role in politics and they don't care about the departments in the campaign. So we have to do the work on our side

to look integrated and have our shit together," he said. "That took some time. You have to develop new trust with people. It's just change

management. It's not complicated; it's just hard."

WHAT THEY ACTUALLY BUILT

Of course, the tech didn't exist for its own sake. It was meant to be used by the organizers in the field and the analysts in the lab. Let's just run

through some of the things that actually got accomplished by the tech, digital, and analytics teams beyond of Narwhal and Dashboard.

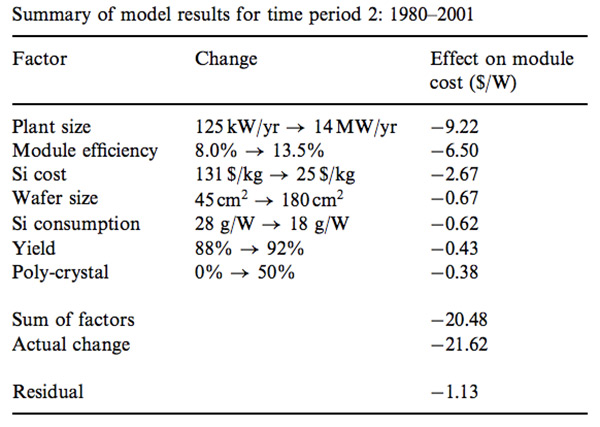

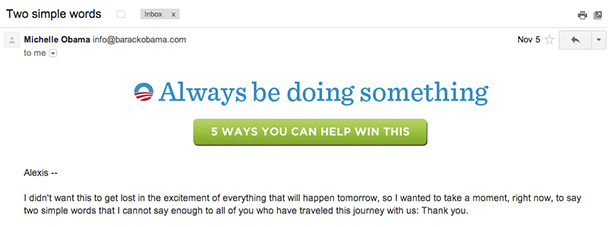

They created the most sophisticated email fundraising program ever. The digital team, under Rospars leadership, took their data-driven strategy to a new

level. Any time you received an email from the Obama campaign, it had been tested on 18 smaller groups and the response rates had been gauged. The campaign

thought all the letters had a good chance of succeeding, but the worst-performing letters did only 15 to 20 percent of what the best-performing emails

could deliver. So, if a good performer could do $2.5 million, a poor performer might only net $500,000. The genius of the campaign was that it learned to stop sending poor performers.

Obama became the first presidential candidate to appear on Reddit, the massive popular social networking site. And yes, he really did type in his own

answers with Goff at his side. One fascinating outcome of the AMA is that 30,000 Redditors registered to vote after President dropped in a link to the Obama voter registration page. Oh, and the campaign also officially has the most tweeted tweet and the most popular Facebook post. Not bad. I would also note that Laura

Olin, a former strategist at Blue State Digital who moved to the Obama campaign, ran the best campaign Tumblr the world will probably ever see.

With Davidsen's help, the Analytics team built a tool they called The Optimizer, which allowed the campaign to buy eyeballs on television more cheaply.

They took set-top box (that is to say, your cable or satellite box or DVR) data from Davidsen's old startup, Navik Networks, and correlated it with the

campaign's own data. This occurred through a third party called Epsilon: the campaign sent its voter file and the television provider sent their billing

file and boom, a list came back of people who had done certain things like, for example, watched the first presidential debate. Having that data allowed

the campaign to buy ads that they knew would get in front of the most of their people at the least cost. They didn't have to buy the traditional stuff like

the local news, either. Instead, they could run ads targeted to specific types of voters during reruns or off-peak hours.

According to CMAG/Kantar, the Obama's campaign's cost per

ad was lower ($594) than the Romney campaign ($666) or any other major buyer in the campaign cycle. That difference may not sound impressive, but the Obama campaign itself aired more than 550 thousand ads. And it wasn't just about cost, either. They could see

that some households were only watching a couple hours of TV a day and might be willing to spend more to get in front of those harder-to-reach people.

Goff described the Facebook tool as "the most significant new addition to the voter contact arsenal that's come around in years, since the phone call."

The digital, tech, and analytics teams worked to build Twitter and Facebook Blasters. They ran on a service that generated microtargeting data that was built by Will St. Clair. It was code named Täärgus Taargüs for some reason. With Twitter, one of

the company's former employees, Mark Trammell, helped build a tool that could specifically send individual users direct messages. "We built an

influence score for the people following the [Obama for America] accounts and then cross-referenced those for specific things we were trying to target,

battleground states, that sort of stuff." Meanwhile, the teams also built an opt-in Facebook outreach program that sent people messages saying,

essentially, "Your friend, Dave in Ohio, hasn't voted yet. Go tell him to vote." Goff described the Facebook tool as "the most significant new addition to the voter

contact arsenal that's come around in years, since the phone call."

Last but certainly not least, you have the digital team's Quick Donate. It essentially brought the ease of Amazon's one-click purchases to political

donations. "It's the absolute epitome of how you can make it easy for people to give money online," Goff said. "In terms of fundraising, that's as innovative as we needed to be." Storing people's payment information also let the campaign receive donations via text messages long before the Federal Elections Commission approved

an official way of doing so. They could simply text people who'd opted in a simple message like, "Text back with how much money you'd like to donate."

Sometimes people texted much larger dollar amounts back than the $10 increments that mobile carriers allow.

It's an impressive array of accomplishments. What you can do with data and code just keeps advancing. "After the last campaign, I got introduced as the CTO of the most technically advanced campaign ever," Slaby said. "But that's true of every CTO of every

campaign every time." Or, rather, it's true of one campaign CTO every time.

EXIT MUSIC

Harper Reed after the election (Photo by Daniel X. O'Neil).

That next most technically advanced CTO, in 2016, will not be Harper Reed. A few days after the election, sitting with his wife at Wicker Park's

Handlebar, eating fish tacos, and drinking a Daisy Cutter pale ale, Reed looks happy. He'd told me earlier in the day that he'd never experienced stress

until the Obama campaign, and I believe him.

He regaled us with stories about his old performance troupe, Jugglers Against Homophobia, wild clubbing and DJs. "It was this whole world of having fun and

living in the moment," Reed said. "And there was a lot of doing that on the Internet."

"I spent a lot of time hacking doing all this stuff, building websites, building communities, working all the time, " Reed said, "and then a lot of time

drinking, partying, and hanging out. And I had to choose when to do which."

We left Handlebar and made a quick pitstop at the coffee shop, Wormhole, where he first met Slaby. Reed cracks that it's like Reddit come to life. Both of

them remember the meeting the same way: Slaby playing the role of square, Reed playing the role of hipster. And two minutes later, they were ready to work

together. What began 18 months ago in that very spot was finally coming to an end. Reed could stop being Obama for America's CTO and return to being "Harper Reed, probably

one of the coolest guys ever," as his personal webpage is titled.

But of course, he and his whole team of nerds were changed by the experience. They learned what it was like to have -- and work with people who had -- a higher purpose than building cool stuff. "Teddy [Goff] would tear up talking about the President. I would be like, 'Yeah, that guy's cool,'" Reed said. "It was only towards the end, the middle of 2012, when we realized the gravity of what we were doing."

Part of that process was Reed, a technologist's technologist, learning the limits of his own power. "I remember at one point basically breaking down during the campaign because I was losing control. The success of it was out of my hands," he told me. "I felt like the people I hired were right, the resources we argued for were right. And because of a stupid mistake, or people were scared and they didn't adopt the technology or whatever, something could go awry. We could lose."

And losing, they felt more and more deeply as the campaign went on, would mean horrible things for the country. They started to worry about the next Supreme Court Justices while they coded.

"There is the egoism of technologists. We do it because we can create. I can handle all of the parameters going into the machine and I know what is going to come out of it," Reed said. "In this, the control we all enjoyed about technology was gone."

We finished our drinks, ready for what was almost certainly going to be a long night, and headed to our first club. The last thing my recorder picked

up over the bass was me saying to Harper, "I just saw someone buy Hennessy. I've never seen someone buy Hennessy." Then, all I can hear is that

music.