By BEN CASSELMAN and RUSSELL GOLD

BEAVER COUNTY, Pa.—Three decades after being devastated by the closing of steel mills, this gritty river valley is hoping its revival will come from cheap natural gas.

The hope doesn't rest on drilling rigs, but on a multibillion-dollar chemical plant that Royal Dutch Shell PLC is considering building here because of a flood of domestically produced natural gas. Community leaders are touting the plant as the first step toward reviving a manufacturing industry many thought was gone for good.

"I never would have expected that as a region we'd have a second chance to be a real leader in American manufacturing," Bill Flanagan of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, a regional business group, told a crowd of locals who came to hear about the chemical plant. "Suddenly we're back in the game."

It isn't just Beaver County reaping the benefits of cheap gas. Plunging prices have turned the U.S. into one of the most profitable places in the world to make chemicals and fertilizer, industries that use gas as both a feedstock and an energy source. And they have slashed costs for makers of energy-intensive products such as aluminum, steel and glass.

"The U.S. is now going to be the low-cost industrialized country for energy," the energy economist Philip Verleger says. "This creates a base for stronger economic growth in the United States than the rest of the industrialized world."

Natural gas is only part of the story. The same hydraulic-fracturing revolution that is freeing gas from shale formations is being used to extract oil. U.S. oil production is up 20% since 2008, and the U.S. government expects it to rise another 12.6% in the next five years.

Economists at Citigroup Inc. earlier this year estimated that increased domestic oil and gas production, and the activity that flows from it, would create up to 3.6 million new jobs by 2020 and boost annual economic output by between 2% and 3.3%.

Others, noting that energy is only a small cost for most industries, see a smaller impact. Economists at HSBC earlier this year estimated the gas boom will add about 1% to gross domestic product over 10 years, not enough to bring down unemployment.

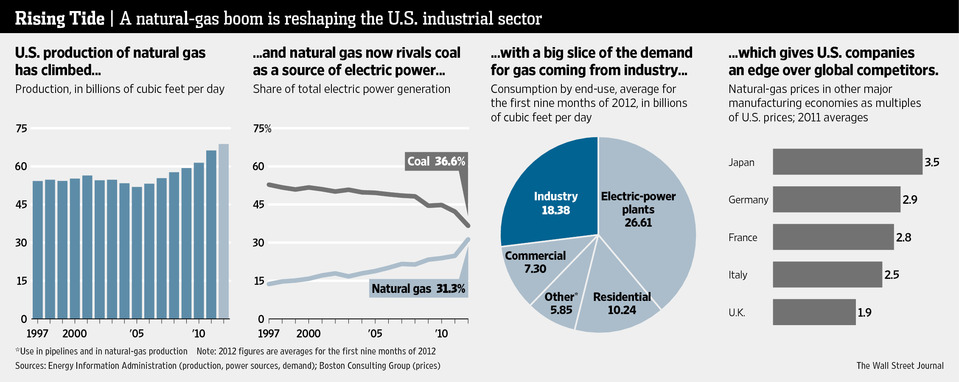

The surge in natural-gas production has the biggest implications. Oil is a world market, so increased U.S. production won't give U.S. petroleum consumers a significant price advantage.

Natural gas, by contrast, is difficult to transport across oceans and is most efficiently consumed in the same continent where it is produced. That means the glut of gas hitting the market will result in the U.S. having lower prices than other major industrial economies for years to come.

In mid-2008, U.S. natural-gas prices topped $12 per million BTUs. The current price is just $3.54 per million BTUs. The U.S. government expects the average price to stay below $5 for another decade, after adjusting for inflation. German and French companies now are paying nearly three times as much for gas as U.S. companies, and Japanese companies even more than that.

Low domestic gas prices have led some U.S. producers to look at shipping gas overseas, where prices are higher. But such projects will cost billions of dollars and take years to complete, and must overcome political opposition from gas consumers worried about higher prices.

A study from the Energy Information Administration earlier this year predicted industrial gas users could expect between a 7% and 19% increase in energy costs due to exports by 2025. Two separate studies see only a modest impact on prices.

In the rundown former steel towns along the Ohio River, natural gas is spurring hopes of an industrial renaissance. Steel mills once lined the Ohio River here, but little of the industry survives. The proposed site of the Shell facility holds one of the few big factories still operating, an 80-year-old zinc plant slated for closure next year.

Known as a "cracker," the Shell chemical plant would take ethane gas—a hydrocarbon found in natural-gas deposits—and turn it into ethylene, the first step in making many plastics.

The ethane would come from the Marcellus Shale, a massive formation of gas-bearing rock that underlies much of Pennsylvania and surrounding states. If the project goes forward, it would be the first such plant built in the U.S. in more than a decade.

Pennsylvania won the project after a three-state bidding war, and some government watchdog groups have criticized the state's package of tax breaks and other incentives as too generous.

But there were few critics among the locals who gathered recently to hear about the plant. Some asked about safety and environmental issues, but mostly the questions centered on one issue: jobs. How many would there be? And would Shell hire locals or import workers from outside? The answers: Shell expects about 400 permanent jobs, but many more than during construction; and it hopes to hire mostly locals.

"I'm four generations in this area. I want my children to stay here," says Sandie Egley after the meeting.

Throughout the 1990s and much of the 2000s, Beaver County's unemployment rate was higher than the U.S. average. That has reversed since the gas boom began to take hold in 2009, with the county's jobless rate consistently below the national mark.

Penna Flame Industries, in the nearby town of Zelienople, is benefiting from cheaper energy. Inside the company's roadside headquarters, propane-fired torches throw off bright orange flames as they heat metal parts like gears or wheels to more than 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, to harden the surfaces. Truck-size ovens run 20 hours a day, burning as much as a million cubic feet of gas per month.

Falling prices have cut the family-owned company's monthly gas bill to between $3,000 and $4,000 per month from as much as $10,000 in 2008. Profits are up. Fuel surcharges imposed on customers during the years of high prices are gone. And the company is making longer-term changes.

Gary Lopus, Penna Flame's general manager, says energy savings—along with low interest rates and other factors—have allowed the company to invest in its future. In a backroom, three yellow robotic arms direct tightly focused flame in preprogrammed patterns.

Pointing to a newly hired robotics technician, Mr. Lopus says: "That guy wouldn't have a job if it wasn't for the robots…When you're not spending as much in other areas, you can spend more on things like this."

Still, the greater Pittsburgh region has lost more than 30,000 manufacturing jobs in the past two decades, and natural gas alone is unlikely to bring them back. The Shell cracker won't employ as many workers as the zinc plant it aims to replace.

And any economic revival will have to contend with the demographic headwinds that are the legacy of a generation of decline: Beaver County lost more than 15,000 residents, 8% of its population, from 1990 to 2010. Those that remain are older, poorer and less likely to have a college degree than the nation as a whole.

Jack Manning, an official with the Beaver Chamber of Commerce, says locals are excited at the opportunities the Shell project could provide, but wary of getting their hopes up. Driving through Aliquippa, a former steel city just up the river from the high school, Mr. Manning gestures to the boarded-up storefronts and vacant lots that line the town's once-thriving main street.

"People get a bit skeptical when politicians come in here and say it'll be better, because they've been hearing it for years," Mr. Manning says.

Natural gas will help some industries immensely, but others less so. It accounts for about 70% of the cost of making fertilizer, and 25% of the cost of making many plastics.

Between 1998 and 2004, fertilizer producers—which use natural gas to make ammonia, the key component in nitrogen fertilizer—shut down more than two dozen U.S. plants, representing close to half of U.S. capacity. Some facilities were literally taken apart and shipped overseas, where gas was cheaper.

Now the trend is reversing. In September, Egyptian industrial giant Orascom Construction Industries announced plans for a $1.4 billion fertilizer plant in Iowa, which the company says would be the first large-scale fertilizer facility built in the U.S. in more than 20 years.

Deerfield, Ill.-based fertilizer maker CF Industries Inc. is planning to spend up to $2 billion boosting its U.S. production through 2016.

"It's been a complete 180-degree change in our thought process," says CF Industries CEO Steve Wilson.

Mr. Wilson and other industry leaders stress that they aren't expecting prices to stay this low forever, but say U.S. plants will be competitive even if prices rise somewhat.

Uncertainty about the long-term direction of natural-gas prices remains one of the biggest obstacles to a gas-driven industrial renaissance. "Look how much the price has changed in the last few years," says Mike Mullis, whose Memphis-based company, J.M. Mullis Inc., helps manufacturers choose sites for new factories. "It's just a wild card right now."

The chemical industry, which like the fertilizer industry saw production shift overseas in the 1990s and early 2000s, is now rushing back to the U.S. Companies such as Dow Chemical Co. and Chevron Phillips Chemical Company LLC have announced plans to build multibillion-dollar chemical plants in Texas, Louisiana and other states.

"We convinced ourselves that this is not a temporary thing," says Peter Cella, chief executive of Chevron Phillips. "This is a real, durable phenomenon, a potential competitive advantage for the United States."

Such projects could have a bigger long-term economic impact than the drilling boom itself. Drilling activity ebbs and flows with prices, and the rigs themselves rarely stay in one community for long. But chemical plants, oil refineries and the factories that use their products can last for decades.

Other winners will be energy-intensive industries like glass manufacturers—as well as companies that will benefit from increased demand for natural gas, such as the makers of turbines for gas-fired power plants.

Then there are industries that do both, such as metals manufacturing. Energy can account for anywhere from 10% to 20% of costs for the metals industry, enough that the decline in gas prices could save some marginal plants.

At the same time, the oil and gas boom has led to new demand for drilling pipe and other metal products, further boosting companies' prospects.

A few miles east of Beaver County, in Brackenridge, metals manufacturer Allegheny Technologies Inc. is building a new $1.1 billion mill, which is set to open in 2014. The plant will produce metals for, among others, chemical plants and the oil and gas industry, which uses high-tech alloys in its pipes and drilling equipment.

The new plant will burn a huge amount of gas, giving it a key advantage against competitors in Europe and Asia.

Allegheny Technologies, which also runs metals-finishing facilities in Beaver County and is headquartered in nearby Pittsburgh, spends $200 million per year on energy. CEO Richard Harshman says U.S. manufacturers now enjoy the lowest natural-gas prices in the world, with the possible exception of Russia.

Sitting in his office overlooking downtown Pittsburgh, Mr. Harshman gestures to the rivers that lead north to Brackenridge and Beaver County. It was the region's rich coal seams and powerful rivers that helped it emerge as an industrial powerhouse in the 19th century, he says. Now the energy industry is again boosting the region's prospects.

"You have to go back 100 years for that to have been the case," Mr. Harshman says. "It's one of the reasons we became a manufacturing powerhouse in the first place."

Write to Ben Casselman at ben.casselman@wsj.com and Russell Gold at russell.gold@wsj.com

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BI747_Natgas_NS_20121023184203.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/AM-AV650_JINVES_C_20121106132020.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BS291_CORPBO_C_20121106193011.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MK-BY541_HPFAIL_C_20121106180144.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MK-BY556_BRIN_C_20121106182411.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/NA-BT449_BADGER_C_20121106163422.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PJ-BK691_SKINNY_C_20121106185353.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BI993_VOICE__C_20121106182811.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BS305_FRBANK_C_20121106192547.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PJ-BK662_georgi_C_20121106183438.jpg)

![[image]](https://webarchive.library.unt.edu/web/20121107195237im_/http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PJ-BK690_carter_C_20121106171952.jpg)

Email Newsletters and Alerts

The latest news and analysis delivered to your in-box. Check the boxes below to sign up.

Thank you !

You will receive in your inbox.