How a German scientist is using test data to revolutionize global learning

|

|

|

The World’s Schoolmaster

Earlier this year, delegations from 16 countries and regions met at the Hilton New York for an unprecedented exchange of ideas and angst: an off-the-record summit on how to improve teaching. For nearly 10 hours, the education ministers of places ranging from Hong Kong to the United Kingdom sat beside their teachers-union leaders and haltingly traded stories of successes and failures. Even the Japanese delegation made it, despite the 9.0 earthquake that had rocked their country less than a week before. (They had slept in their offices to ensure they’d make their flights.)

One person at the table, however, was not representing any country: Andreas Schleicher, quietly tapping notes into his computer, was there on behalf of children everywhere—or at least on behalf of their data. And without him, the meeting never would have happened. A rail-thin man with blue eyes, white hair, and a brown Alex Trebek mustache, Schleicher works for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a bureaucrat without portfolio. And in recent years, he has become the most influential education expert you’ve never heard of.

Arne Duncan, President Obama’s secretary of education, consults with Schleicher and uses his work to compel change at the federal and state levels. “He understands the global issues and challenges as well as or better than anyone I’ve met,” Duncan said to me. “And he tells me the truth.” This year, U.K. Education Secretary Michael Gove called Schleicher “the most important man in English education”—never mind that Schleicher is German and lives in France.

The story of how an introverted German scientist came to judge and counsel schools around the world is an improbable one. As a mediocre student in Hamburg, Schleicher did not particularly care about his classes—to the distress of his father, who was a professor of education. Later, at an alternative high school, teachers encouraged Schleicher’s fascination with science and math, and his grades improved. He finished at the top of his class, even winning a national science prize. At the University of Hamburg, Schleicher studied physics. He had no interest in his father’s field, considering it too soft. Then, out of curiosity, he sat in on a lecture by Thomas Neville Postlethwaite, who called himself an “educational scientist.” Schleicher was captivated. Here was a man who claimed he could analyze a soft subject in a hard way, much the way a physicist might study schools. At the time, 1986, the education establishment was dominated by tradition, theories, and ideology. “You had people dealing with every subject,” Schleicher tells me, “except looking at reality.”

Schleicher’s father did not approve. “His feeling was that you can’t measure what counts in education—the human qualities.” But Schleicher began collaborating with Postlethwaite anyway, creating the first international reading test.

Back then, countries subjected only small numbers of select students to such tests—or abstained from sampling altogether. “I remember everyone telling you, ‘We have the best education system in the world,’” Schleicher says. To his data-driven mind, this was madness. How can everyone be the best?

In April 1996, after Schleicher had joined the OECD, he and his colleagues pitched the idea of designing a smarter, more ambitious test than any that had preceded it—a way to shift the OECD from measuring inputs (like spending on schools) to outputs (how much kids learn). Many education ministers were skeptical, but Thomas Alexander, Schleicher’s boss, convinced them that their countries could not remain economically competitive unless they could measure what their students actually knew.

More at The Atlantic

The Atlantic

The Atlantic

|

Election 2012

The Atlantic's full coverage of the battles for the White House, Senate, and more. Read more › |

On Newsstands Now

Subscribe and SAVE 59%

10 issues JUST $2.45/COPY

Browse back issues of The Atlantic that have appeared on the Web. From September 1995 to the present, the archive is essentially complete, with the exception of a few articles, the online rights to which are held exclusively by the authors.

See All Back Issues: September 1995To The Present »

-

George McGovern, Congressman, Senator, Liberal, Dies at 90

George McGovern, Congressman, Senator, Liberal, Dies at 90

-

Iran Is Ready to Talk About Their Nuclear Program (or Not?)

Iran Is Ready to Talk About Their Nuclear Program (or Not?)

-

Bloomberg Endorses Joe Biden (Obama and Romney Can Wait)

Bloomberg Endorses Joe Biden (Obama and Romney Can Wait)

-

Why Amtrak Keeps Breaking Ridership Records and Will Continue To Do So

Why Amtrak Keeps Breaking Ridership Records and Will Continue To Do So

-

Vienna's Naked Subway Woman Adds To Rich History of Nude Commuting

Vienna's Naked Subway Woman Adds To Rich History of Nude Commuting

-

Where Americans Come to Hate Muslims: Dearborn

Where Americans Come to Hate Muslims: Dearborn

Most Popular

- 1

- SNL's Bruno Mars Episode: 5 Best Scenes

- 2

- On War and Peace, George McGovern Will Die Vindicated

- 3

- The Revenge of the Soccer Moms

- 4

- Keeping the 'Mentally Incompetent' From Voting

- 5

- What Happens If TV Goes the Way of Music and Newspapers?

- 6

- The Past Ain't Even the Past

- 7

- Inside Foxconn #3: Some Dormitories

- 8

- Why Women Still Can’t Have It All

- 9

- Why We're Still Waiting on the 'Yelpification' of Health Care

- 10

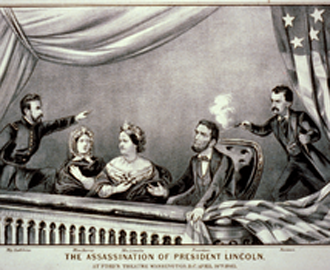

- A Guy Who *Saw* Lincoln Get Shot Was on a TV Show in 1956 That Is Now on YouTube

Gestalten TV: Tessa Farmer

Gestalten TV: Tessa Farmer  Designer Reza Abedini

Designer Reza Abedini  The Great Transition

The Great Transition

Join the Discussion

After you comment, click Post. If you’re not already logged in you will be asked to log in or register. blog comments powered by Disqus