A growing cornucopia of organics

Organic farming in the Ninth Federal Reserve District continues to sprout in fields and on dinner plates.

Dave Walter - Contributing Writer

Published January 1, 2008 | January 2008 issue

Do you shop the organic sections at the local grocery store because the fruits and vegetables there are grown without chemicals? Do you favor a natural-foods store when shopping for produce because it offers such a good selection of organics? Is it your habit to make a weekly pilgrimage to your local farmers' market because you know you can find organic meat, cheese and produce, often grown on farms close to where you live?

If so, you are part of the growing market in organic foods, a trend that is being fed by a growing organic agricultural sector in the Ninth District and nationwide.

Ninth District states have long played a large role in the nation's agricultural economy, and they have an outsized role in the organic sector as well. District states are among production leaders in many crops and livestock, thanks in part to strong growth in the number of organic farms and the total acreage being plied.

Organic farming makes up a small percentage of the agricultural economy—in fact, 2005 was the first year that each of the 50 states had some organic farmland. Of total farms and farmland in the district, organics account for less than 1 percent of each category. Still, the small portions belie strong growth. Organic farming started expanding significantly in the late 1990s in both the district and the United States and has been growing robustly since then, though at different rates and for different foodstuffs in each state.

From the ground up

As a fraction of overall food sales, organics made up only about 2.5 percent of U.S. retail sales in 2005, according to a study commissioned by the Organic Trade Association. But as the shelves of local grocery stores demonstrate—not to mention those at retailing giant Wal-Mart—organic sales have increased close to 18 percent per year since 1997 and were about $14 billion in 2005. According to the Nutrition Business Journal, the organic food market is expected to reach about $24 billion by 2010.

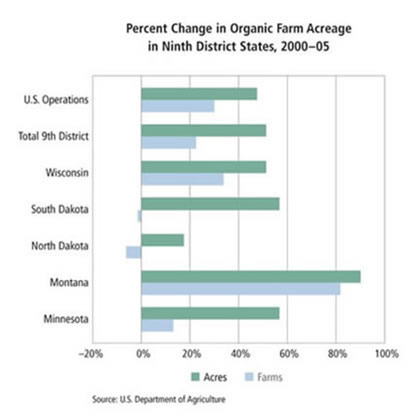

All that organic good stuff has to come from somewhere, and data from the Economic Research Service (the research arm of the U.S. Department of Agriculture) show that much of it is being grown or raised in district states. With 735,000 total organic acres, district states have almost 30 percent of organic acreage in the lower 48 states. Growth in organic acreage in district states increased a healthy 52 percent from 2000 to 2005, slightly more than the 46 percent increase nationwide (see chart). Montana had the largest growth, adding 108,000 acres, a 90 percent increase, while North Dakota had the smallest bump in organic acreage, at 18 percent. Almost three-quarters of district organic acreage is cropland, but each state's mix of cropland and range/pastureland varies; Minnesota has the highest percentage of cropland (90 percent) and Montana the lowest (55 percent).

The number of organic farms in the district in 2005—about 1,400—constituted almost 17 percent of all organic farms in the country. Their numbers increased by 22 percent from 2000 to 2005-a bit lower than the 29 percent growth of organic farms in the lower 48 states. Montana led district states in terms of farm growth, at 81 percent, while the Dakotas saw organic farm numbers decrease. And a lot has likely taken place since 2005; the Minnesota Department of Agriculture estimates that the number of certified organic farms there jumped by almost 100 farms (or 22 percent) just in 2006.

South Dakota has easily the smallest proportion of organic farms to all farms, at about one for every 350 traditional farms. Wisconsin has the highest ratio, at about one for every 130 traditional farms. However, these numbers probably underestimate the proportion of organic farms to "full-time" traditional farms because the USDA counts a farm as any operation with $1,000 or more in annual income, which means it counts a high number of hobby farms. Given the high entry barriers to growing organics, there are probably comparatively fewer organic hobby farms.

Specific reasons for the increase or decrease in organic farms and acreage in each state, as well as the differences in organic intensity among states, are difficult to discern from the data. Geography, the traditional style of agriculture practiced, market forces and state policy probably all play a role. In a telephone conversation, Meg Moynihan, organic and diversification specialist at the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, pointed out that Minnesota formed an organic program at the state level earlier than most, which may have helped the state develop its organic sector earlier than others.

Jeff Knudson, program manager for the North Dakota Department of Agriculture, thought that consolidation of farms played a role in the decrease of organic farms in North Dakota in the first half of this decade. As well, some farming regions are more entrenched in traditional farming, which makes the transition to organics more difficult because the general support structure—professional advice, organic inputs, even other farmers to bounce ideas off—is not in place for organics.

Old McDonald's organic farm

District states have established themselves as leaders in numerous organic categories, at least on the basis of various farm-size measures (organic production figures are not available, so measures are in terms of livestock head or acreage). Like the traditional farm sector, organic farming in district states is heavily weighted toward grains and common livestock (see chart below). In terms of national production, district states have little presence in organic fruits or vegetables, mostly because these crops fare better elsewhere.

Wisconsin's herd of almost 17,000 organic dairy cows in 2005 was the largest in any state, which is no surprise as Wisconsin is historically a major dairy producer. An organic influence emanates from Organic Valley Family of Farms, based in the western Wisconsin town of LaFarge. Organic Valley is one of the two largest producers of organic milk in the United States. Wisconsin was also fourth in organic beef cows, though its herd of just 3,200 head is maybe more indicative of the small national scale of organic beef right now.

Montana, third in the nation in conventional wheat production, was tops in the organic variety in 2005, with 56,000 acres. North Dakota is fourth in organic wheat acres and first in oats, and it grows half of the nation's organic oilseeds. Minnesota and Wisconsin have been consistent leaders in growing organic corn; their combined acreage was almost 30 percent of the U.S. total in 2005. Minnesota is also tops in soybean acreage by a wide margin.

Behind the growth and overall presence in various organic niches are a number of drivers. The most obvious one is significant price premiums that farmers receive for their organic product compared to the nonorganic equivalent. A USDA study published in May 2007 reported that organic milk prices were about 100 percent higher than conventional milk prices in 2004. In another study released by the USDA in December 2006, prices for organic broiler chickens were about 200 percent higher than those for conventional broilers from January 2004 to June 2006. The average price premium for organic eggs in the same period was even higher, about 278 percent. A report from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture shows a consistent premium for organics.

Other tools are being developed so farmers—and sectors connected to the ag industry—have better organic price information at their fingertips. Two private organizations, Organic Business News and the Rodale Institute, publish organic price lists, which track current prices on a wide variety of commodities. While better than no price information at all, these lists are based on bid prices, not market prices, for organic commodities and so are less reliable than conventional commodity price data.

A check with the Rodale price list, called the New Farm Organic Price Index, shows healthy organic price premiums across most crops. For example, in the Minneapolis market, the price for organic #2 yellow corn was 76 percent higher than the conventional price, and the price for organic hard red wheat was 24 percent higher than the conventional price in early October.

Agricultural Marketing Service, an agency within the USDA, is also responding to growing demand from market players for organic price information. Jim Bernau from AMS in Des Moines, Iowa, said that earlier this year his department began collecting price information from organic commodity handlers to generate price averages that reflect market values. But don't go running to the Web just yet; Bernau said creating a reliable, user-friendly database is a slow process, and he didn't offer any estimates as to when such a system might be operable.

Planting money?

Price premiums for organics tend to ebb and flow over time as supply and demand fluctuate in both organic and conventional markets. But price premiums for many organic foodstuffs are firmly above their conventional counterparts, at least for the moment.

The premium itself stems from several factors, including consumers' perception of greater value in organic products, which makes them more willing to pay higher prices. Fast-growing demand has also been able to stay ahead of rising production—at least so far—preventing surpluses that have historically plagued traditional crop and livestock production and pushed prices down. Agricultural economists assume that if supply catches up with demand—through either scaled-up production or increased importation of organic foods from elsewhere—price premiums will shrink.

But neither do price premiums mean that organic farmers' paychecks are proportionately fatter. For starters, organic farmers typically face higher production costs. Though chemical input costs drop to virtually zero, organic farming is much more labor-intensive than traditional farming. For organic livestock, the cost of organic feed is often significantly higher than nonorganic feed.

How all the organic pluses and minuses balance out in the financial end is mostly unknown: There is no clear evidence regarding the profitability of organic vis-à-vis conventional farms. Some research suggests organic farming is less profitable; other research says it is more profitable. Most of the research lacks both scale and longevity. It is clear that there are profits to be had in organic farming; what's less clear is how much of profits are due to the price premium. Some research suggests that organic farming could continue to be profitable without much of any price premium, thanks to lower input intensity, letting and helping Mother Nature do more of the work.

Jim Riddle, the organic agricultural coordinator at the Southwest Research and Outreach Center in Lamberton, Minn., posited that when a farm goes organic, there is a shift from reliance on chemicals to reliance on labor input and management ability for profitability.

Some believe profitability is not a big motivator for organic farmers. Riddle thinks that income is only one of several reasons for farmers to go organic. Some farmers dislike the health aspects of using synthetic fertilizers and herbicides. Some are burned out on being tied to the nonorganic system of needing to increase farm size, pay for chemicals and be indebted to the bank. Riddle also observed that embracing organic agriculture may be a generational issue—younger farmers seem to be more open to the idea of organic farming and more willing to learn new systems. Several state organic agriculture coordinators mentioned that some farmers' ethical views on land use were factors that led them to switch.

In spite of recent increases in conventional commodity prices, state officials are not seeing organic farmers revert back to conventional production. Price premiums for organics have remained, and the commitment to organics has to be strong in the first place because the entry costs are considerable.

A future growing season?

The outlook for organics, especially in the near view, is very positive by most accounts. Demand is projected to remain strong, and high entry costs and lack of organic support networks—nearby feed sources, processors and operational consultants—mean that oversupply due to a fast ramp-up in production is unlikely, at least for now.

But as one might expect, farmers are seeing the opportunity. For example, agriculture officials report that idle land, including acres enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program, is getting pulled into organic production. CRP acres are particularly strategic because some automatically qualify for organic certification—which requires that land be documented as free of synthetic chemical application for at least three years—and need comparatively little preparation to bring into production.

Still, organic growth has sometimes been a dance of two steps forward, one step back. For example, organic meat is one of the fastest growing segments, yet much of the organic beef in stores is shipped in from Argentina. Doug Crabtree, organic certification program manager from Montana, mentioned that it is a struggle to get ranchers there to switch to raising organic beef, despite the available pastureland and cattle know-how from being among the top 10 states in beef cattle production. Several factors, including consumer confusion over meat labeling, inadequate organic meat processing infrastructure, a lack of locally available corn for cattle finishing and the seasonal production flows of a northern climate conspire to make ranchers resist the shift to organics, he said.

Montana's growth in organic wheat production has been slowed by recent strong commodity prices. Montana is one of the major producers of non-organic wheat, and Crabtree mentioned that as other states switched from raising wheat in favor of corn for ethanol production, the price of wheat increased, offering Montana wheat growers less incentive to convert to organic wheat production. It is harder to make changes when the status quo is doing well for you.

But neither is the status quo attractive to all conventional farmers. Gary Holthaus of the Northern Plains Sustainable Agriculture Society tells a story of a couple he knows who farmed conventionally for years, raising hogs. Then, in their 60s, they decided that system didn't work for them, so they switched to organics, raising Scottish Highland cattle, as well as ponies, poultry and goats, working harder than ever but "having the time of their lives."

Editor Ronald A. Wirtz contributed to this article.

Annual Reports

Annual Reports fedgazette

fedgazette