President’s Speeches

Planning for Liftoff

Narayana Kocherlakota - President

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Gogebic Community College

Ironwood, Michigan

September 20, 2012

Planning for Liftoff - Video Summary text

Note1

Thank you very much for that generous introduction, and thank you for the opportunity to join all of you here today. It is a pleasure to be back in the Upper Peninsula. I was in Marquette two years ago, and Bob Jacquart insisted that I come to Ironwood on my next trip to the U.P. And I have to say—he was right. This is a beautiful part of the world. Speaking of Bob, I would like to thank him for all of his work in helping put this event together, along with James Lorenson and Linda Gustafson here at Gogebic Community College. I would also like to thank everyone who joined us at Bob’s factory this morning to discuss economic issues facing businesses in the region. It was an informative meeting, and also a very instructive tour; so thanks again, Bob, for making all of that happen.

As Bob knows from his service on the Bank’s Advisory Council on Small Business and Labor, discussions about current conditions and people’s business plans are important for monetary policymakers. As you can imagine, I have access to reams of data about the economy, but data don’t always tell the whole story. That’s why opportunities like this are valuable to me. Likewise, I look forward to your questions and comments at the end of my talk, as I always find those to be great learning opportunities. However, before we proceed any further, I need to remind you that the following views are my own, and not necessarily those of others in the Federal Reserve.

In my remarks today, I’ll briefly discuss the objectives of the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC, which is the monetary policymaking arm of the Federal Reserve. Next, I’ll present a pictorial review of the evolution of macroeconomic data over the past five years.

With that background, I will then turn to a discussion of monetary policy. My jumping-off point is a phrase in the FOMC statement issued last Thursday. In that statement, the Committee said that it “expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens.” My main message today is that the FOMC can provide additional monetary stimulus by making this sentence more precise in the form of what I’m going to call a liftoff plan: a description of the economic conditions that would lead the Committee to contemplate the initial increase in the fed funds rate above its currently extraordinarily low level.2

I will suggest the following specific contingency plan for liftoff:

As long as the FOMC satisfies its price stability mandate, it should keep the fed funds rate extraordinarily low until the unemployment rate has fallen below 5.5 percent.

The fed funds rate is a short-term interbank lending rate that is the FOMC’s usual vehicle for influencing credit conditions. I’ll be much more precise later about the meaning of the phrase “satisfies its price stability mandate.” Briefly, though, I mean that longer-term inflation expectations are stable and that the Committee’s medium-term outlook for the annual inflation rate is within a quarter of a percentage point of its target of 2 percent. The substance of this liftoff plan is that, as long as longer-term inflation expectations remain stable, the Committee will not raise the fed funds rate unless the medium-term outlook for the inflation rate exceeds a threshold value of 2 1/4 percent or the unemployment rate falls below a threshold value of 5.5 percent. Note that neither of these thresholds should be viewed as triggers—that is, once the relevant cutoffs are crossed, the Committee retains the option of either keeping the fed funds rate extraordinarily low or raising the fed funds rate.

Thus, my proposed liftoff plan contains a specific definition of the phrase “a considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens.” In my talk, I will argue that this specificity—about an event that may not take place for four or more years—will provide needed current stimulus to the economy.

FOMC Objectives

Let me begin by describing the monetary policy objectives of the FOMC. Congress has specified in the Federal Reserve Act that the FOMC should make monetary policy so as to promote price stability and maximum employment. These two objectives—price stability and maximum employment—are typically termed the FOMC’s dual mandate. In January, the FOMC issued an important consensus statement of long-run principles and strategies. In that statement, the FOMC pointed out that it is difficult to fashion a quantitative definition of “maximum employment.”

In contrast, the January statement does provide a specific definition of price stability as representing a goal, over the longer run, of 2 percent inflation. But there are a couple of reasons why this definition of price stability is not as operational as one might like. One issue is that monetary policy affects inflation with lags. Policymakers are generally thinking about making current choices so as to influence the annual inflation rate in about two years’ time. Thus, monetary policy choices made toward the end of 2012 should be evaluated in terms of their impact on the annual inflation rate in the calendar year 2014. As a result, policymakers’ choices are shaped by what I will call the medium-term outlook for the inflation rate—that is, the forecast for the annual inflation rate in two years.3

A second operational issue is that in some circumstances, it may be appropriate to follow policies that lead the medium-term outlook for inflation to deviate from the long-run target. Indeed, most central banks—including ones that do not have an employment mandate—find that this kind of flexibility is desirable. Of course, the public may cease to regard 2 percent as a meaningful long-run target if it sees too much of a gap between 2 percent and the Committee’s medium-term outlook for inflation. A key question is: How much leeway around 2 percent is appropriate?

The Committee has made no formal decision about this issue, and my own thinking continues to evolve. But I currently believe that allowing the medium-term outlook for inflation to deviate from 2 percent by a quarter of a percentage point in either direction would provide sufficient flexibility to the Committee, while posing no threat to the credibility of the long-run target. I’ll provide more details on my thinking about this issue later in the talk.

To sum up, the FOMC defines its price stability mandate as a 2 percent inflation target over the longer run. When operationalizing this definition, though, it is necessary to take into account the lags associated with monetary policy and to allow for some medium-term flexibility around the long-run target. Given these considerations, in my view, the FOMC can be said to be satisfying its price stability mandate as long as its medium-term outlook for inflation is between 1 3/4 percent and 2 1/4 percent, and longer-term inflation expectations remain stable.

A Look Back and Associated Monetary Policy Considerations

I’ve described the FOMC’s objectives in making monetary policy. Let me turn now to describing the evolution of the economy over the past few years. I will focus on three variables that are of great interest to the FOMC: output, unemployment and inflation. I’ll then briefly discuss the implications of this recent macroeconomic history for monetary policy decision-making.

Economists typically measure the output of a country through its gross domestic product, adjusted for inflation—what’s called real GDP. This graph shows the behavior of real GDP over the past 10 years. The gray area on the graph marks the time that was dated as the Great Recession by the National Bureau of Economic Research. During this time, real GDP fell by about 5 percent. The gray bar tells us that the economy is considered to have been in recovery since the middle of 2009—that is, for over three years.

But the recovery has been, at best, a slow one. The black line on the chart depicts how, as of December 2007, we would have typically expected real GDP to grow, given long-run averages. Over the course of the recession, a gap emerged between real GDP and this black line. By the middle of 2009, that gap was about 10 percent. This is not surprising—pretty much by definition, we expect a gap of this kind to open up during recessions. But, historically, large declines in real GDP have been followed by sufficiently strong output growth to close this gap within a few years. During the recent recovery, though, the gap has actually widened noticeably.

Given the sluggish recovery in national output, it is not surprising that labor markets are also healing slowly. This is often described in terms of the behavior of the national unemployment rate, which we can see on this graph. The unemployment rate was 5 percent in December 2007 and peaked at 10 percent in late 2009. It has since fallen to 8.1 percent—still well above historical norms.

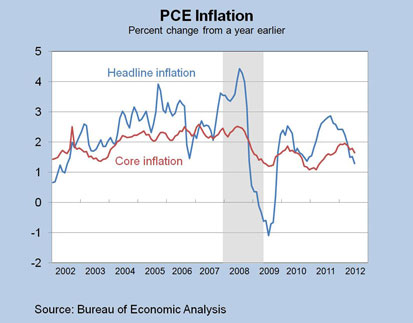

The next graph shows the evolution of the inflation rate, based on the personal consumption expenditures price index. The black line is headline inflation, which includes food and energy goods and services. It is quite variable, in large part because of substantial transitory shocks to oil prices. The red line is core inflation, which strips away food and energy goods and services. This series is much smoother—hence, it is generally thought to do a better job of tracking underlying inflation pressures in the economy than headline inflation does. Inflation fluctuated notably in 2008 and 2009, in large part due to movements in energy prices. Currently, both core and headline inflation rates are below the FOMC’s target inflation rate of 2 percent.

That’s a brief review of the past five years. Real output has grown over the past three years, but remains well below what one would expect in light of historical growth patterns in the United States. Unemployment remains well above 2007 levels. Inflation is below the Fed’s target inflation rate of 2 percent.

What do these data imply about the appropriate stance of monetary policy? The FOMC has two mandates—to promote price stability and to promote maximum employment. Whenever an organization has two goals, it is logically possible that those goals may conflict. Indeed, many observers have expressed exactly this concern about the FOMC’s current position.

But these data and public communications from last week’s FOMC meeting reveal that there is no such tension at this time. The unemployment rate is elevated above a level that the Committee sees as consistent with its employment mandate. Most FOMC participants’ medium-term outlooks for PCE inflation are at 2 percent or below. These observations imply that, by increasing monetary accommodation, the Committee can better meet its employment mandate while still satisfying its price stability mandate.

The FOMC’s public communications also suggest that this lack of tension between its two mandates is likely to continue for some time to come. Most FOMC participants currently project that, in the long run, an unemployment rate less than 6 percent is consistent with 2 percent inflation. These forecasts suggest that violations of price stability are unlikely to occur until the unemployment rate is considerably lower than its current level of 8.1 percent.

A Liftoff Plan

I’ve described the evolution of macroeconomic data over the past five years, how the FOMC currently sees little tension between its two mandates and how this lack of tension between the mandates seems likely to continue. I now return to the key message that I introduced at the beginning of this talk: the importance of developing a liftoff plan—that is, an economic contingency plan for the initial increase in the fed funds rate above its current extraordinarily low level.

I’ll start with some background. Right now, the FOMC has two types of accommodation in place. First, it is targeting the federal funds rate at between 0 and 0.25 percent. The Committee expects to keep that interest rate extraordinarily low at least through mid-2015. Second, the FOMC has bought a large amount of long-term government-issued and government-backed assets—indeed, last week the Committee announced its intention to expand its holdings of these assets over the coming months. Both of these forms of accommodation are designed to put downward pressure on interest rates. This downward pressure is intended to discourage firms and households from saving or buying financial assets, and instead encourage them to spend. When firms and households spend, their extra demand for goods and services pushes upward on employment and upward on prices.

I think that it is safe to say that, relative to historical norms, the current stance of monetary policy is quite unusual. In June 2011, the FOMC released a statement describing its exit strategy—that is, the sequence of steps involved in returning monetary policy to a more normal stance. However, that 2011 statement said nothing about the conditions that would trigger the initiation of this exit strategy. This omission is problematic. The current economic impact of both forms of accommodation—low interest rates and asset purchases—depends on when the public believes that accommodation will be removed.

To understand this critical point, consider two possible scenarios. In the first, the public believes that the FOMC will initiate liftoff once the unemployment rate hits 7 percent. In the second, the public believes that the FOMC will defer initiation of liftoff until the unemployment rate hits 6 percent. The higher unemployment rate in the first scenario means that monetary policy will be tightened sooner, which, in turn, will lead to the unemployment rate being higher for longer. Foreseeing that, people will save more in the first scenario than in the second, to protect themselves against these higher unemployment risks. Because they save more, they spend less, and there is less economic activity. In other words, the FOMC can provide more current stimulus if people believe that liftoff will be triggered by a lower unemployment rate.

With this observation in mind, the remainder of my remarks will describe what I see as an appropriate liftoff plan.4 The proposed plan is the following:

As long as the FOMC is continuing to satisfy its price stability mandate, it should keep the fed funds rate extraordinarily low until the unemployment rate has fallen below 5.5 percent.

As discussed earlier, by “satisfy its price stability mandate,” I mean that longer-term inflation expectations are stable, and the Committee’s outlook is that the annual inflation rate in two years will be within a quarter of a percentage point of the target inflation rate of 2 percent.

Why is this liftoff plan an appropriate one? I argued earlier that the FOMC can provide more current stimulus by using a lower unemployment rate threshold for liftoff. Of course, additional monetary stimulus will give rise to more inflationary pressures, and those pressures are problematic because they could lead the FOMC to violate its price stability mandate. However, in my view, the Committee should choose the lowest unemployment rate threshold that it sees as unlikely to generate a violation of the price stability mandate.

I noted earlier that the FOMC’s current projections for the long-run unemployment rate are well below 8.1 percent. These projections suggest that there will be little upward pressure on inflation until the recovery is sufficiently robust that the unemployment rate has fallen back to a level that is more consistent with historical norms. I see an unemployment threshold of 5.5 percent as being readily rationalized under this perspective, although slightly higher or slightly lower thresholds should not materially affect the impact of this plan.5

The proposed liftoff plan does allow the FOMC to contemplate raising the fed funds rate if the Committee’s medium-term inflation outlook rises above 2 1/4 percent. However, the following chart shows that recent historical evidence suggests that this possibility is unlikely to occur. It documents that the medium-term inflation outlook has not risen above 2 1/4 percent in the last 15 years.6 Thus, this historical evidence suggests that, as long as the unemployment rate remains above 5.5 percent, it seems unlikely that the price stability mandate would be violated.

In any event, the liftoff plan does not say that the Committee will raise the fed funds rate when the medium-term inflation outlook exceeds 2 1/4 percent—only that it could. The Committee’s decision in this context would hinge on a delicate cost-benefit calculation that would weigh the inflation increases against the employment gains. That policy conversation would, I conjecture, be a challenging one. Among other issues, it could well involve a reassessment of the long-run unemployment rate that is consistent with 2 percent inflation.7

In the same vein, the unemployment rate of 5.5 percent should be viewed as only a threshold to initiate a policy conversation, not as a trigger for action. For example, it is possible that macroeconomic shocks could lead the Committee’s medium-term outlook for inflation to be below 2 percent when the unemployment rate falls below 5.5 percent. At that point, the Committee might want to defer initiating exit, and the liftoff plan allows the Committee to consider doing so.

Before concluding, I want to be clear about the economic mechanism by which the proposed liftoff plan generates stimulus. First, it does not generate stimulus by having the FOMC tolerate higher rates of inflation, as has been espoused by many observers. I am doubtful about the efficacy of the inflation-based approach. I suspect that many households would believe that their wage increases would not keep up with the higher anticipated inflation rates. Those households would save more and spend less—exactly the opposite of the policy’s aim. In any event, I think that this approach is a risky one for central banks to use, because it requires them to raise inflation expectations—but not too much.

Thus, the liftoff plan that I’ve discussed only applies when the FOMC satisfies its price stability mandate. How then does the proposed liftoff plan generate stimulus? The plan recommends that the FOMC clearly communicate its intention to pursue policies that are fully supportive of much higher levels of economic activity. Thus, the plan commits to keeping the fed funds rate extraordinarily low until the unemployment rate is much nearer historical norms, as long as inflation remains under control. With that commitment, households can anticipate a lower path for unemployment, and they can save less to guard against the risk of job loss. People will spend more today, and that will drive up economic activity.8

Conclusions

I’ve spent much of my time describing what I see as an appropriate liftoff plan. I’ve proposed that, given current Committee thinking about the economy’s productive capacity, the Committee should plan on deferring exit until the unemployment rate falls below 5.5 percent. Critically, there are important inflation safeguards embedded in the plan: The Committee could consider initiating liftoff if its medium-term inflation outlook ever exceeds 2 1/4 percent. The evidence from the past 15 years suggests that this event is unlikely to occur.

President Charles Evans of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago has also proposed what I’m calling a liftoff plan. As I said last year in answer to a media query, I very much liked his approach to thinking about the problem. Those familiar with his plan will see that my thinking has been greatly influenced by his. This is perhaps hardly surprising, since he sits next to me at every FOMC meeting!

My building on President Evans’ creative proposal in this fashion is, I think, indicative of how the Federal Open Market Committee operates. The making of monetary policy under Chairman Ben Bernanke’s leadership is a distinctly collaborative process. Obviously, we don’t always agree with one another. It would be surprising if we did in such unusual economic conditions. But we learn continually from each other’s points of view. In that way, I believe that we can start to make progress on the challenging economic problems we face.

Thanks for listening, and I look forward to taking your questions.

Endnotes

1 I thank Dave Fettig, Terry Fitzgerald, Sam Schulhofer-Wohl and Kei-Mu Yi for their comments.

2 The liftoff plan is a particularly important example of the kind of public contingency plan for monetary policy that I described in speeches late last year (Kocherlakota 2011a, 2011b).

3 More specifically, the medium-term outlook for inflation in fourth quarter 2012 refers to the outlook for the rate of increase in the PCE price index from fourth quarter 2013 to fourth quarter 2014.

4 The FOMC’s June 2011 statement of exit strategy principles provides a temporal connection between the first interest rate increase and other exit steps, like sales of assets.

5 Technically, we can rationalize an unemployment threshold of 5.5 percent as follows. Suppose that the inflation outlook πe is related to the current unemployment rate u through the following (crude) Phillips curve relationship: (πe - 0.02) = -α(u - u*), where u* is the long-run unemployment rate under appropriate monetary policy. In this kind of relationship, estimates of α < 0.5 are generally thought to be empirically plausible. (For example, such a small slope is consistent with the fact that inflation is currently projected to be so close to target, while unemployment remains elevated relative to most assessments of its natural rate.) The central tendency of FOMC participants’ estimates of u* is between 5.2 percent and 6 percent. For any u* in this range, and given the upper bound of 0.5 on the Phillips curve slope, πe < 2.25 percent (that is, is consistent with price stability) as long as u > 5.5 percent.

6 Strictly speaking, the chart does not depict the FOMC’s medium-term outlook for the PCE inflation rate, because the Committee does not formulate a collective quantitative outlook. Instead, for the period 1997-2006, the chart depicts the medium-term outlook for PCE inflation prepared for December FOMC meetings by Federal Reserve staff (Greenbook). Beginning in 2007, FOMC participants released summary information about their projections for inflation conditioned on their individual assessments of appropriate policy. The chart depicts the midpoint of the central tendency of those medium-term outlooks (Summary of Economic Projections, or SEP) for inflation from the fourth quarter of each calendar year.

7 In previous speeches, I’ve discussed the experience of Sweden after its financial/housing/banking crisis in the early 1990s. I’ve described how monetary policymakers in Sweden eventually concluded—correctly—that the crisis and its aftereffects had caused significant permanent damage to the functioning of their labor markets. It is possible that the evolution of the data may lead the FOMC to conclude the same about the U.S. economy. It would then raise its estimate of the long-run unemployment rate consistent with 2 percent inflation.

8 See Werning (2012, sections 4.2 and 5) for an extensive discussion of this mechanism.

References

Kocherlakota, Narayana. 2011a. “Further Thoughts on Making Monetary Policy.” Speech at Harvard Club of Minnesota. Minneapolis, Minn., Oct. 21.

Kocherlakota, Narayana. 2011b. “Making Monetary Policy: Public Contingency Planning Using a Mandate Dashboard.” Speech at Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Stanford, Calif., Nov. 29.

Werning, Iván. 2012. “Managing a Liquidity Trap: Monetary and Fiscal Policy.” Working paper. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Events

Events