Climate Change

Northeast Impacts & Adaptation

Northeast

On This Page

Key Points

- More frequent heat waves in the Northeast are expected to increasingly threaten human health through heat stress and by affecting air pollution.

- As temperatures rise, farms and fisheries will likely face increasing problems with productivity, potentially damaging livelihoods and the regional economy.

- More frequent heavy rains and sea level rise are likely to increase flooding in the Northeast.

Related Links

EPA:

- Climate Change and Water: Northeast

- EPA, A Student's Guide to Global Climate Change: Effects on People and the Environment

- EPA Region 1 (including the Northeast states of CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, and VT)

- EPA Region 2 (including the Northeast states of NJ and NY)

- EPA Region 3 (including the Northeast states of DE, MD, PA, and WV)

Other:

- USGCRP, Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States: Northeast

- USDA, Office of the Chief Economist. Global Climate Change: Resources

- USGCRP, Synthesis Assessment Product 4.3: The effects of climate change on agriculture, land resources, water resources, and biodiversity in the United States (PDF)

- USGCRP, Synthesis Assessment Product 4.4: Preliminary review of adaptation options for climate-sensitive ecosystems and resources

- U.S. Climate Change Science Program, Synthesis Assessment Product 4.6: Analyses of the effects of global change on human health and welfare and human systems

-

Northeast Climate Impacts Assessment

-

New York City Panel on Climate Change (PDF)

The Northeast includes dense cities and sparsely populated towns. The region extends from the coast to inland plateaus and mountains. Its climate varies as much as its geography. Portions of West Virginia, the region's southern-most state, typically experience more than 20 days per year of 90°F temperatures. In contrast, northern areas of Maine typically experience only one day per year above 90°F. [1]

View enlarged image

View enlarged image

By the end of the 21st Century, New Hampshire summers may feel more like North Carolina today. Source: USGCRP (2009)

Over the last several decades, the Northeast has experienced noticeable changes in its climate. Since 1970, the average annual temperature rose by 2°F and the average winter temperature increased by 4°F. [2] Heavy precipitation events increased in magnitude and frequency. For the region as a whole, the majority of winter precipitation now falls as rain, not snow. [2] Climate scientists project that these trends will continue.

As seen in the map, New Hampshire's summers could be as warm as North Carolina's summers are today by the end of this century. Over the same period, Boston is projected to experience an increase in the number of days reaching 100°F — from an average of one per year between 1961 and 1990 to as many as 24 days per year by 2100. [2] Under a higher emissions scenario, Philadelphia and Hartford could see as many as 30 days per year with temperatures reaching 100°F. [2]

Precipitation and Sea Level Rise Impacts

View enlarged image

View enlarged image

Boston will experience an increase in the number of days over 100°F. Source: USGCRP (2009)

The combination of a projected increase in heavy precipitation and likely sea level rise may lead to more frequent, damaging floods in the Northeast. [2] The region's dense population and large coastal cities, including New York, place this region at risk for significant losses.

Overall, the amount of precipitation throughout the Northeast is projected to increase. Less winter precipitation falling as snow will likely increase the number and impact of flooding events. Sea level rise, storm surges, erosion, and the destruction of important coastal ecosystems will likely contribute to an increase in coastal flooding events, including the frequency of current "100-year flood" levels (severe flood levels with a one-in-100 likelihood of occurring in any given year). By the end of the century, New York City may experience a 100-year flood every 10 to 22 years, on average. [2] Damages to coastal property and infrastructure could impact the insurance industry. New York State alone has more than $2.3 trillion in insured coastal property. [2]

For more information on climate change impacts on coastal resources, please visit the Coastal page.

Impacts on Human Health

Hot summer days can worsen air pollution, especially in urban areas. In areas of the Northeast that currently face problems with smog, inhabitants are likely to experience more days that fail to meet air quality standards. More frequent heat waves and lower air quality can threaten the health of vulnerable people, including the very young, the elderly, outdoor workers, and those without access to air conditioning or adequate health care. [2] People who live in Northeastern cities are particularly at-risk, since the region is generally not as well adapted to heat as warmer regions of the country. Northeastern cities are likely to experience some of the highest numbers of heat-related illnesses and deaths, compared with the rest of the nation. [3]

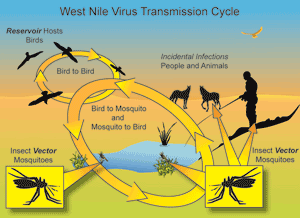

More frequent extreme precipitation events would increase the risk of waterborne illnesses caused by sewage overflows and pollutants entering the water supply. Combined with extremely hot days, the increase in heavy rain events is likely to create more favorable conditions for the breeding of mosquitoes that carry West Nile Virus. [2] Furthermore, extreme storms can damage infrastructure, such as dams, levees, and bridges, resulting in loss of life.

For more information about the impacts of climate change on human health, please visit the Health page.

Impacts on Agriculture and Food Supply

View enlarged image

Cranberry harvest in New Jersey. Source: USDA (2006)

Average temperatures in the Northeast are projected to increase and precipitation patterns are projected to continue to change. These changes are likely to affect the types of crops cultivated in the Northeast. Large portions of the region may become unsuitable for growing some fruit varieties and some crops, such as apples, blueberries, grain, and soybeans. With much warmer average temperatures, cranberries — a staple of Cape Cod's agriculture — may no longer grow in southeastern Massachusetts. [2] Similarly, by the end of the century, only a small portion of the Northeast may be suitable for maple syrup production. In contrast, the region could see a longer growing season for a number of other crops, which would provide potential benefits to society.

Dairy production is important to the Northeast's agricultural economy. Increases in temperature will likely reduce milk yields and slow weight gain in dairy cows. [2] The projected increases in temperature would negatively affect operations, since production costs would increase with reductions in milk and meat production. In addition, without cooler nighttime temperatures, many cows would experience continued heat stress that could ultimately result in loss of cattle.

Fisheries are also an important part of the region's economy and food supply. Although the Northeast experienced a significant increase in lobster catch over the last few decades, there is variability within the region. Northern areas of the region fared better. Warmer temperatures in the northern regions of the Gulf of Maine led to better survival rates of lobsters and more suitable lobster settlements. This indicated a northern shift in suitable lobster habitats. Northern regions are likely to continue to benefit from warmer water temperatures. Meanwhile, warmer waters have negatively affected southern areas of the region. In these areas, lobster catches peaked in the mid-1990s and dropped sharply after temperature-sensitive bacteria struck coastal Massachusetts in 1997. [2] Declines in lobster catches in southern areas of the Northeast are likely to continue and worsen because of temperature-related disease. [2]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on agriculture and food supplies, please visit the Agriculture and Food Supply page.

Impacts on Forests

Heat stress and decreased soil moisture are likely to negatively affect the productive ability of several tree types in the Northeast. Some of the trees that are currently common across the Northeast, such as maple, birch, and beech, could experience a significant northward shift in their growing region. [2] As the ranges for spruce and fir trees shrink, several of the animal species that live in these forests could be at risk of losing their habitats. [2]

While warmer temperatures would directly affect tree health, these conditions could also allow certain destructive invasive species to thrive. The hemlock woolly adelgid is of particular concern in the Northeast. This highly destructive insect has worked its way through hemlock forests from Georgia to Connecticut. Hemlock forests provide habitat for a variety of species, including several unique types of birds (the blue-headed vireo and Blackburnian warbler). The hemlock woolly adelgid could completely wipe out hemlock populations in the Northeast, destroying habitat for these birds, among other species. [4]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on forests, please visit the Forests page.

Impacts on Winter Recreation

View enlarged image

View enlarged image

Location of ski resorts in the Northeast — warmer temperatures could cause most to close by the end of the century. Source: USGCRP (2009)

The Northeast region has many winter recreation opportunities, including snow sports (skiing, snowmobiling, snowshoeing, dog sledding) and ice-based activities (ice fishing and skating). These activities contribute about $7.6 billion annually to the Northeastern economy. Projected increases in temperature could reduce snow cover and shorten winter snow seasons, limiting and altering these types of activities.

The average length of the ski season may decline to less than 100 days, and winter nights are expected to be warmer. Ski resorts may require more artificial snowmaking to produce snowpack. Artificial snowmaking requires additional water and energy, increasing costs to the resorts. The impacts of these changes may decrease the economic viability of operating ski resorts in the Northeast. [2]

To learn more about what the Northeast is doing to adapt to climate change impacts, please visit the adaptation section of the Northeast Impacts and Adaptation page.

References

[2] USGCRP (2009). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States . Karl, T. R., J. M. Melillo, and T. C. Peterson (eds.). United States Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

[3] CCSP (2008). Analyses of the effects of global change on human health and welfare and human systems . A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Gamble, J.L. (ed.), K.L. Ebi, F.G. Sussman, T.J. Wilbanks, (Authors). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA.

[4] CCSP (2008). The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture, Land Resources, Water Resources, and Biodiversity in the United States . A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Backlund, P., A. Janetos, D. Schimel, J. Hatfield, K. Boote, P. Fay, L. Hahn, C. Izaurralde, B.A. Kimball, T. Mader, J. Morgan, D. Ort, W. Polley, A. Thomson, D. Wolfe, M. Ryan, S. Archer, R. Birdsey, C. Dahm, L. Heath, J. Hicke, D. Hollinger, T. Huxman, G. Okin, R. Oren, J. Randerson, W. Schlesinger, D. Lettenmaier, D. Major, L. Poff, S. Running, L. Hansen, D. Inouye, B.P. Kelly, L Meyerson, B. Peterson, and R. Shaw. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA.