A Dangerous Worksite

The World Trade Center |

||

|

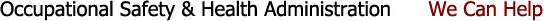

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks against

our nation on September 11, 2001, thousands of

America’s workers responded by joining hands to

recover the remains of those who had been lost

and to reclaim the ground where the twin towers of

the World Trade Center once stood. Working around

the clock, under unimaginably dangerous conditions,

they endured and prevailed.

Out of the chaos emerged a strong and effective public-private partnership that ensured protection for the workers at the site. OSHA joined forces with the City of New York, construction contractors, labor unions, and all levels of government in a pledge to recover the site with no further loss of life. The partners achieved their goal. On May 30, 2002, when the recovery was complete, not another life had been lost, and illness and injury rates were far below the national average for the industries involved in the recovery. John L. Henshaw Assistant Secretary of Labor for Occupational Safety and Health U.S. Department of Labor |

|

|

|

||

|

THE GREEN LINE A green line, painted around the perimeter of the World Trade Center (WTC) site, defined the recovery area. Within and around this boundary, OSHA worked for 10 months with its partners in safety and health to protect the well-being of workers on the site. Within that space, no workers lost their lives in the recovery effort that followed the tragedy of September 11, 2001. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

OSHA’S ROLE OSHA’s strategy at the WTC was to pursue collaboration while suspending enforcement and providing consultation, guidance, and technical assistance with a sound safety and health plan. Our goal from the start was protection, not citation. From the very beginning, OSHA knew that the recovery of the WTC site would be no ordinary demolition project. At the center stood a mountain —all that remained of two skyscrapers that once soared 110 stories high and defined the New York City skyline for decades. OSHA had addressed many of these hazards before, but not on such a vast scale. No one could deal with the catastrophe alone. No one group had all of the answers, equipment, experience—let alone the personnel—to protect the safety and health of workers at the site. How would they accomplish that goal? The answer lay in partnership. Informal collaboration of initial responders had begun early. But soon, representatives from every group involved in the recovery effort would formally agree to join in a team effort to protect the safety and health of workers at the disaster site. Secretary of Labor Elaine Chao led the signing of the formal partnership. Speaking at the ceremony in New York City on November 20, 2001, Chao declared, “American workers—from city, state, and federal government agencies, trade associations, contractors, and labor organizations—formed a partnership to reclaim this site and recover our fellow citizens. They’ve done this with pride, dignity, talent, hard work, and dogged determination.” |

|

|

|

||

|

THE WORKERS

A flood of workers soon poured onto the site. Here is a partial list:

|

PARTNERSHIPS

Signatories to the World Trade Center Emergency Project Partnership Agreement:

IDENTIFYING RISKS AND HAZARDS Many hazards threatened the safety and health of site workers. They included risks caused by cranes lifting beams of unknown weight and improperly handled compressed gas cylinders that might explode, as well as threats posed by falls and falling objects, hot steel, confined spaces, Freon, and much more. A list of the most dangerous risks facing the WTC recovery workers follows: |

|

|

|

||

|

Identifying Risks and Hazards:

CRANES More than 30 cranes, including some of the largest in the world, were at work in uncomfortably close quarters inside the green line. In what has been described as an intricate balance of motion and timing, the cranes lifted loads of twisted steel and compacted rubble in an environment fraught with the potential for accidents. High winds, rain, unstable ground, and uncertain loads added to this dangerous mix. OSHA saw the need for special focus to address the growing concern over crane operations. The agency consulted with various partners and then launched a Joint Crane Inspection Task Force. Composed of representatives from OSHA, contractors, and the International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE), the task force spent two days inspecting 17 cranes inside the green line. They found numerous serious hazards on more than half the cranes. Most of the hazards involved crane set-up, rigging, and hoisting practices. Crane set-up continued to be an issue because the giant steel towers often rested on unstable platforms as fires burning deep in the pile caused the cranes to shift. The task force identified hoisting personnel with man-baskets as the most serious concern. For example, in the early days of the recovery, workers modified garbage dumpsters with welding torches, then hooked them to cranes to lower workers into the pile. |

|

|

|

||

|

The crane safety effort yielded further success

when inspection teams learned that faulty

equipment might be put back into service. The

task force inspected 222 pieces of rigging and

found 81 deficient in one sector of the site.

Employers in the other three sectors soon began

to remove suspect rigging before the task force

arrived. OSHA reported 151 safety interventions

involving crane operations, about 21 percent of

all hazard corrections made inside the green line.

The number of problems dropped consistently

after organization of the task force.

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Identifying Risks and Hazards:

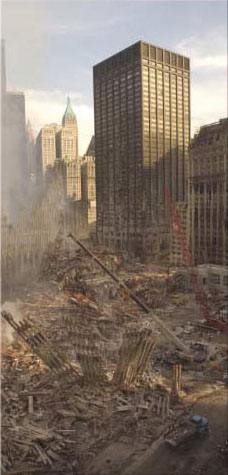

HEAVY EQUIPMENT The combination of rescue workers performing recovery operations side by side with demolition workers using heavy equipment in tight quarters and under great emotional stress posed unique challenges. Ordinarily, rescue workers are not present when machines such as excavators, grapplers, and debris trucks are operating. This was not the case here. OSHA consulted with construction personnel, labor representatives, and emergency responders to find a simple solution that made a big difference. The wearing of brightly colored reflective vests made the workers visible to the equipment operators and reduced the potential for serious injury or even death. A mandatory distance between rescue workers and heavy equipment provided additional protection. The sheer size and instability of the debris pile posed further complications. The mountain of mangled debris rose six stories above ground and descended seven below; voids within caused ever-changing shifts and constant hazards. With heavy equipment operating on such unstable surfaces, there was special cause for concern. Yanking twisted steel from one spot could undermine another and send an operator into a hole several stories deep. Safety officials worried daily about the potential for such falls. They kept a close eye on the number of workers operating heavy equipment and on their proximity to others working on the pile. There were many “near misses,” including an unattended crane that fell 30 feet when the platform of rubble on which it sat gave way. Constant vigilance—and in a few cases, fate and good luck—averted near disaster. |

|

|

|

||

|

Identifying Risks and Hazards:

FALLS AND FALLING OBJECTS Falls are routinely the most common cause of workplace injuries in the United States. At the WTC site, workers often had to operate several stories above ground and in very uncertain environments. The odds for disaster were great. OSHA set up special training in fall prevention methods and technology for the workers and their supervisors to help them reduce or eliminate the risks. Meanwhile, the New York City Department of Design and Construction (DDC) worked hard to reduce the hazards of falling debris and structural instability posed by the surrounding buildings. They brought in contractors to secure the premises, install vertical netting, and erect sidewalk sheds and canopies to further protect the workers. OSHA safety monitors and other safety professionals constantly roved the site, identifying and addressing hazards. Safety personnel often interrupted an activity to ask that workers tie-off or find a safer way to proceed. They also checked scaffolding, performed job risk analysis, and made sure workers understood safety rules for aerial lifts. On one occasion, a load of debris fell directly on a spot where firefighters had stood only moments earlier. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Identifying Risks and Hazards:

EXPLOSIONS Numerous compressed gas cylinders used by burners to cut steel beams and rebar were scattered around the site. These cylinders included oxygen and acetylene tanks, both extremely hazardous if not handled properly. In the early days of the rescue effort, these tanks were largely unsecured, lying haphazardly on the ground. To reduce this hazard, OSHA joined forces with the Fire Department of New York to patrol the site and ensure that contractors followed proper storage and handling procedures. The potential for explosions was always present at the site. In one case, a fuel tank with tens of thousands of gallons of diesel fuel was buried seven stories below ground. With smoldering fires, a rupture could have been disastrous. Once workers located the tank, it was safely emptied, and the fuel was removed from the site. The parking garage under the WTC held nearly 2,000 automobiles, each tank holding an estimated five gallons of gasoline. When recovery workers reached the cars, they found that some had exploded and burned while others remained intact. Building 6, the former site of OSHA’s Manhattan Area Office, housed many federal agencies, including the U.S. Customs Service. More than 1.2 million rounds of their ammunition, plus explosives and weapons, were stored in a third-floor vault to support their firing range. OSHA worked closely with other government agencies to determine what protective measures were necessary so that the ammunition could be safely removed. |

|

|

|

||

|

Identifying Risks and Hazards:

HOT STEEL Even as the steel cooled, there was concern that the girders had become so hot that they could crumble when lifted by overhead cranes. As a result, additional safeguards were put in place to limit the dangers associated with lifting the damaged steel and to protect the workers in the vicinity. Another danger involved the high temperature of twisted steel pulled from the rubble. Underground fires burned at temperatures up to 2,000 degrees. As the huge cranes pulled steel beams from the pile, safety experts worried about the effects of the extreme heat on the crane rigging and the hazards of contact with the hot steel. And they were concerned that applying water to cool the steel could cause a steam explosion that would propel nearby objects with deadly force. Special expertise was needed. OSHA called in structural engineers from its national office to assess the situation. They recommended a special handling procedure, including the use of specialized rigging and instruments to reduce the hazards. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Identifying Risks and Hazards:

FREON Huge underground tanks held more than 200,000 pounds of Freon stored to cool the seven buildings of the WTC complex. This had been the largest air-conditioning system in the country. OSHA personnel were concerned that workers entering areas below grade could be exposed to Freon gas, a known, heavier-than-air, invisible killer. After a leaking tank was discovered, agency staff and the site construction manager carried out special sampling for months until all the tanks were uncovered and safely removed. Identifying Risks and Hazards: CONFINED SPACE OSHA has investigated hundreds of cases of carbon monoxide poisoning across the country. Often this hazard is not immediately apparent, and what may seem to be an open-air atmosphere is really a more deadly confined space. Rescue and recovery workers entered collapsed buildings where the atmospheric hazards from fire and toxic fumes could have been fatal. Besides the usual hazards in confined spaces, the site conditions at the WTC posed the additional risk of structural instability. The DDC designated certain areas for special attention. For example, a sudden and catastrophic release of Freon could overcome workers performing demolition and recovery operations inside collapsed buildings. OSHA helped DDC establish safe entry protocols for these areas. |

|

|

|

||

|

LOOKING BACK

OSHA’s commitment to the WTC recovery involved more than 1,000 agency employees working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, alongside other federal, state and local agencies to ensure the safety and health of workers at the site. At the height of this effort, 75 OSHA staff worked the site each day and OSHA personnel provided more than 15,000 work shifts. OSHA

After September 11, 2001, not one life was lost inside the green line during the recovery effort. LESSONS LEARNED OSHA learned a great deal at the WTC site, lessons that can help the agency improve its own emergency preparedness while also helping employers prepare for emergency response. |

EMPLOYER EMERGENCY EVACUATION PLANS

OSHA suggests that workplaces review and practice their plans with an emphasis on the following:

EMERGENCY RESPONSE PARTNERSHIPS Emergency response partnerships, with clear lines of authority for all functions at a site and with special emphasis on safety and health, should be created immediately to promote effective disaster site management. In addition, OSHA recommends the following as key elements for emergency response partnerships to consider in planning for disasters: EMERGENCY TRAINING For first responders and federal law enforcement agencies:

|

|

|

|

||

|

OUTREACH

Emergency responders, managers, and incident commanders should:

|

FIT TESTING

Emergency responders at all levels of government should be routinely fit-tested for respirators. COMMUNICATION

TRANSPORTATION

THE FUTURE OSHA continues to work with other federal agencies across government to improve cooperation and collaboration in the event that a coordinated response on such a massive scale is ever needed again. If the need arises, OSHA will be ready. OSHA 3193-11-03 Photography credit (listed from top to bottom): 1, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 2, Shawn Moore/DOL; 3, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 4, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 5, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 6 & 7, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 8 & 9, Michael Rieger/FEMA; 10 & 11, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 12 & 13, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 14, Shawn Moore/DOL; 15, Andrea Booher/FEMA; 16 & 17, Gil Gillen/OSHA. |

|

|

|

||

OSHA:

|

||

|

||

Newsletter

Newsletter RSS Feeds

RSS Feeds Print This Page

Print This Page

Text Size

Text Size