Science Features

The Arkansas River at Great Bend, Kansas, on July 13, 2012. Lying west of Isaac’s rain reach, the river was drier still on September 10.

More than three quarters of the contiguous United States still faces abnormally dry conditions in spite of scattered relief from rains generated by tropical storm system Isaac. As seen on the U.S. Drought Monitor, exceptional drought — the worst category — persists in the very center of the nation from Nebraska south to Texas, east through Missouri and Arkansas to the Mississippi Valley. Much of Georgia is also in exceptional drought.

Drought: the slow but costly disaster

Drought is the nation’s most costly natural disaster, far exceeding earthquakes, tornados, hurricanes and floods. FEMA has estimated that the annual average cost of drought in the United States ranges from $6 to $8 billion. (By comparison, the annual costs of flooding are in the $2 to $4 billion range.) Unlike flooding, drought does not come and go in a single episode. Rather, it often takes a long time for drought to begin to impact an area, and it can fester for months or even years.

In order to reduce the impacts of drought, governments and managers rely on objective and unbiased scientific information about trends in streamflow, precipitation, and other factors that contribute to drought, so that they can understand where drought is occurring, how long it is likely to impact an area, and where drought is likely to strike next.

What about Isaac’s effects on the current drought?

The obvious question comes from both expert and casual observers: What difference did tropical system Isaac make in drought-stricken areas?

NOAA records show that Hurricane Isaac made landfall in southern Louisiana the evening of August 28 and then tracked north-northwest, losing its tropical character over Missouri on September 1 and then merging with another frontal zone to move on into the Ohio Valley. This NASA graphic of rainfall based on satellite measurements shows that Isaac’s rainfall was concentrated to the east of its tropical storm center. (100 mm is about 4 in. of rain.)

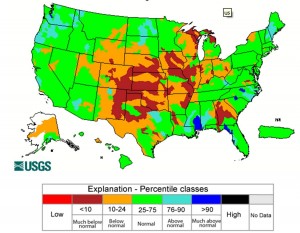

One week after Isaac officially dissipated (9/1), this real-time map of national stream flow from USGS WaterWatch (below normal 7-day average streamflow compared to historical streamflow, updated 9/8) shows that streamflows have returned to normal or higher levels in the middle and lower Mississippi Valleys and the Ohio Valley where much of Isaac’s related precipitation fell.

However, while real-time streamflow levels from USGS WaterWatch are an essential aspect of measuring drought, stream and river conditions are not the only drought indicator.

Drought is a bigger concept than streamflow can show

The national Drought Monitor is the official report detailing drought conditions. This complex map service paints a fuller picture of drought than just stream flow information. In addition to relying heavily on USGS streamgage data, this map also incorporates soil moisture, agricultural information, satellite data, and precipitation.

The map — a joint product of NOAA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the National Drought Mitigation Center — is prepared in consultation with scientists from several agencies, including the USGS. It portrays a comprehensive geographic assessment of areas experiencing drought, as well as the severity of drought. This map has important economic significance because it is used by many states as the basis for declaring a drought emergency and requesting federal funding.

You can see that, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (updated 9/4), extreme or severe levels of drought persist in parts of Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio — states to which Isaac’s rains did come in varied amounts.

The next obvious question might be: Why didn’t Isaac make more of a difference in the drought?

That’s a complex inquiry that involves lots of issues like precipitation rates and volumes, water runoff, groundwater levels, and soil moisture. Let’s look for a broader answer in a story about accumulated precipitation deficit that’s no less true for its simplicity.

A Story of Drought: The Water Bank

USGS WaterWatch map of monthly-average streamflow for August 2012. Note how rain from Isaac accelerated the monthly average east of New Orleans.

It can be useful to think of drought as a water bank account held by Mother Nature. When it rains, Mother Nature makes a deposit into Earth’s water bank account. When it stops raining, Mother Nature is obliged to withdraw water from the soil and from vegetation for “payment” to the atmosphere; this is done through evapotranspiration. The longer she goes without making water deposits, the greater the amount of water that gets withdrawn from the soil, as well as from other storage accounts like lakes and reservoirs, and the greater her water deposits (i.e., precipitation) will have to be to bring the account back up to what it was before the drought started.

That’s essentially what’s going on when one huge storm system with its sudden rains seems to make little immediate difference in a drought. Mother Nature may have hit the million-dollar lottery with Isaac and is making big deposits into her terrestrial account. But she needs to make two or three more deposits like this to get back to the starting point of local average conditions of water deposits and withdrawals.

Looking ahead on drought

In addition to the U.S. Drought Monitor, which tracks current and historic drought conditions, every month the National Weather Service produces a Drought Outlook, with bi-weekly updates based primarily on precipitation forecasts.

The latest long-range report, released on September 6 and looking ahead to November 30, indicates that drought is likely to develop, persist, or intensify across much of the Great Plains (including Texas but not the Dakotas) and all or parts of the Rocky Mountain and Western states (excluding Arizona and Washington).

Drought conditions are likely to improve in Louisiana, Alabama, the Dakotas, the upper Mississippi Valley, and the Ohio Valley. Arkansas, western Tennessee, and Georgia will see lesser degrees of improvement.

Links and resources

For local details and impacts related to drought, please contact your State Climatologist or Regional Climate Center.